Last week, I looked at the average number of films a director is likely to make in their career, and also how many directors work on the average film.

Last week, I looked at the average number of films a director is likely to make in their career, and also how many directors work on the average film.

Today I am taking into account the gender of directors and looking at how the experiences of male and female directors differ.

As a quick reminder, my dataset is of all fiction feature films produced around the world between 1949 and 2018 (over a quarter of a million movies). You’ll find more detail on this in the Notes section at the end of the article and in last week’s piece using the same dataset.

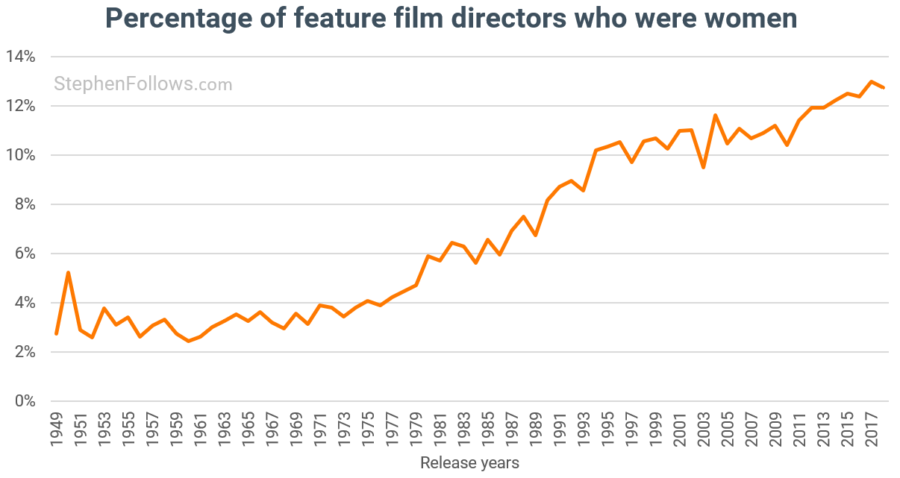

What percentage of film directors are women?

It should come as no surprise to anyone (least of all readers of this blog) that women make up a minority of film directors. Female representation was at just 2.7% in 1949 and started to increase in the 1960s. At the start of the 21st century it reached 10.7% and by 2018 stood at 12.7%.

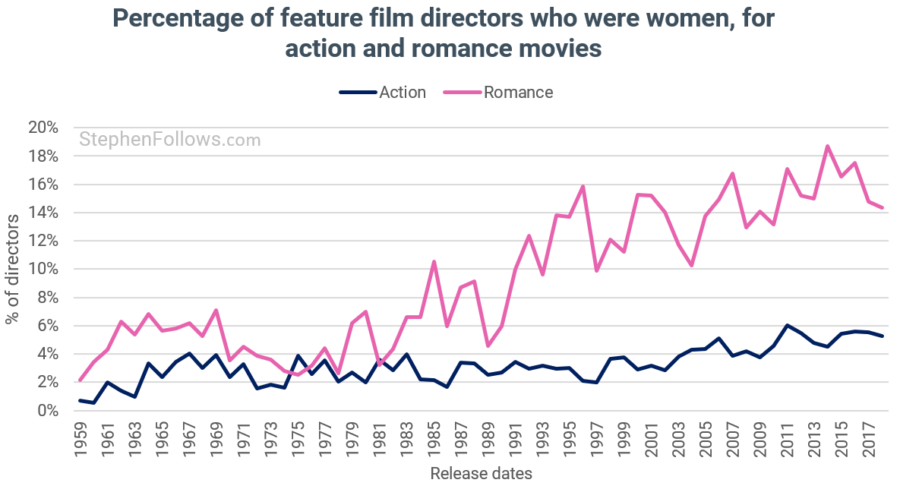

I’m not going to break down these figures by genre as (a) there are so few female directors for most of the 20th century, and (b) there’s no way of displaying it in a readable way without tripling the length of this article. But I did want to highlight that some genres have seen faster growth of female directors than others.

For example, while female representation among directors of action movies has increased over the past sixty years, it has done so at a much slower speed than among romantic films.

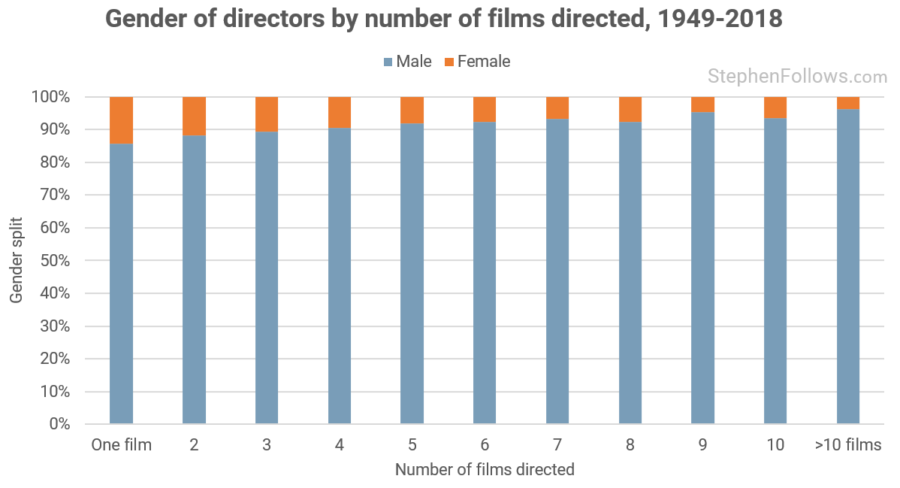

Are male or female directors more likely to make a second film?

As we saw last week, most people who direct a feature film do not get a chance to direct a second. If we split the data by gender of director, we discover that female directors have been considerably less likely to make a second film than their male counterparts. Across the seventy year period, 28.8% of women directed more than one film whereas for men the figure sits at 39%.

The chart below shows the gender split among directors, based on how many films they directed between 1949 and 2018.

While those figures are accurate, they don’t paint the full picture. As we’ve already seen, the number of female directors has increased over the past seventy years, during which time the rate of directors of either gender shooting a second film has fallen. This means that if we just take the overall seventy-year average, we would see fewer second films directed by women, which does not accurately reflect the situation as it is today.

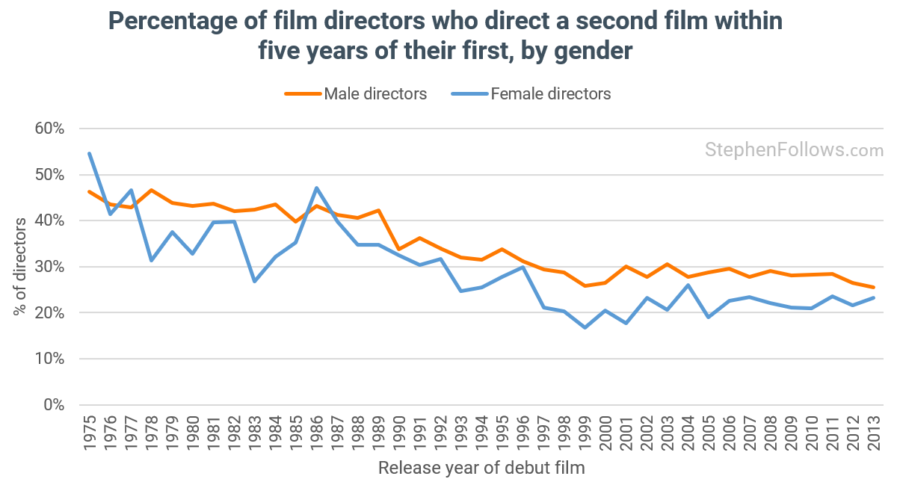

To get a better picture of the differences, we need to ask a narrower question than the seventy-year average. The chart below shows the percentage of directors who made a second film within five years of their first film, for each year between 1975 and 2013.

1986 was that last time that female directors were more likely than men to direct a second film. But the gap is much smaller than we saw in previous years, with the 2013 figures being 25.6% for male directors and 23.3% for female directors.

I have chosen to focus on the past forty years, not the full seventy for which I have data, as there were so few female directors before then as to make the data not statistically significant.

Further Reading

If you would like to read more about the topics raised in today’s research then you may enjoy the following articles:

- My study of film directors in the UK film industry https://stephenfollows.com/gender-inequality-in-the-uk-film-industry

- Gender diversity among film professionals working in sales and distribution https://stephenfollows.com/gender-diversity-in-film-sales-distribution

- My study into gender inequality among UK film and TV writers https://stephenfollows.com/major-new-study-into-gender-inequality-among-uk-film-and-tv-writers

Notes

The data for today’s research came from a number of places, principally IMDb, The Numbers, Wikipedia, Box Office Mojo and OMDb. My dataset is of all fiction feature films made and listed on those sites. Genre classifications were from IMDb, where possible.

The data for today’s research came from a number of places, principally IMDb, The Numbers, Wikipedia, Box Office Mojo and OMDb. My dataset is of all fiction feature films made and listed on those sites. Genre classifications were from IMDb, where possible.

To determine a director’s public gender, I used publicly available data, pronouns (such as in biographies) and first name analysis (i.e. if 99% of people called Daniel are male then I have regarded every Daniel with an unknown gender as male). I appreciate that this research takes no account of gender fluidity or other forms of self-identification. That’s not a conscious choice but rather a consequence of doing research at this scale. If anyone can suggest a way of taking this on board in the research process then I am very keen to hear it. Please drop me a line and we can talk it through.

If there was anyone for whom I could not reliably determine a gender, then they were not included in the charts which show a percentage split between male and female directors. Although this is not ideal, I have no reason to think that these people skew towards one gender over another, and they were also a small percentage of my overall dataset.

For the vast majority of the period I studied, directors are extremely likely to have publicly identified in a binary manner, no matter their true feelings or identity. This research speaks to how directors are judged from the outside and it’s the public-facing gender identity that matters most when it comes to discrimination.

Finally, I have tried to be respectful to all in my choice of language when discussing gender and identity. If I’ve misspoken somewhere, drop me a line and I’ll fix it. I aim to use the word “women” where possible as it relates to identity, not biological sex. The only exception is where it would be grammatically incorrect to do so – both “woman” and “female” are nouns but only “female” is an adjective and a modifier (i.e. “female directors” is correct while “women directors” is not).

Studies of this nature are needed into other under-represented areas, taking into account class, race, socio-economic status, location, to name but a few. Sadly it is much harder to study these topics at the scale and depth I can for gender. I am always on the lookout for ways to do so – please do get in touch with any ideas. Click here to read more about my (as-yet-incomplete) attempts to study race in film.

Epilogue

If you have thoughts on why today’s data looks the way it does, please do drop a comment below. I have been careful to just present the statistics, not provide explanations as to what’s happening. Partly because I certainly don’t have all the answers, but also because we should always be careful to split the data from the explanation.

If you are interested in my views on the topic then I suggest you read the third section of my ten-year study into film directors in UK film. In the first section my co-authors and I presented the data, in the second we looked at how people become directors and it’s only in the third where we put forward theories as to why the gender disparity is the way it is (and suggest possible remedies). For today’s research, I will leave my views out and allow people to comment below.

Let’s keep the comments kind, considerate and fact-based. If you stick to those principles, all views are welcomed.

Comments

Fascinating as usual! Thanks for doing this deep dive!

Thanks for this. I went to the BIFA female filmmakers long list dinner in December 2018 which was a lovely event. Many of the women there were first time feature length film makers – Producers and Directors etc. It was a great evening and I met lots of lovely people but I found it depressing and not surprising how many conversations I had along the lines of ‘I’m not sure I can do it again, so hard, so many sacrifices that had to be made to my family/ personal life, not enough support/ money etc’

I’d be really interested in a study regarding race in film and socio-economic circumstances. I know I wouldn’t have been able to finish my feature documentary if I hadn’t been able to put some of my own money in… (I know you’re not supposed to do that!) and it basically involved juggling various paid jobs, 3 kids and producing the film on the side. Not a great business model going forward…!

Thanks again.