One of the reasons it’s hard to make your first movie is that much of the information you need is not available. While we can all read granular box office figures online, it’s often hard to reliably discover how much a movie cost to make and it’s near impossible to know how they spent that money.

One of the reasons it’s hard to make your first movie is that much of the information you need is not available. While we can all read granular box office figures online, it’s often hard to reliably discover how much a movie cost to make and it’s near impossible to know how they spent that money.

And so I’m pretty excited to share today’s research. It’s a collaboration with Wayne Marc Godfrey, film producer and financier of more than 125 independent feature films. Later this year, he’s launching a new receivables and collections platform for creators and distributors called purely.capital. In the lead-up to purely.capital’s launch, we’re working together on a few articles to shine a light on the financial side of independent film.

First up, we collated a dataset of 107 budgets, ranging from micro-budget movies right up to Hollywood studio tentpoles, to give you a sense of how budgets change as they increase.

A primer in feature film budgets

A film’s budget needs to serve many masters. On the one hand, it has to predict every cost the filmmakers will encounter in creating the finished film and allow for every penny spent to be recorded. On the other hand, it needs to be short and easy to read for investors and producers who want to focus on the big picture.

Therefore, there are usually three ways of presenting a movie budget:

Therefore, there are usually three ways of presenting a movie budget:

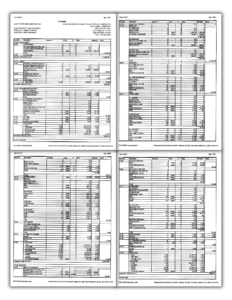

- The full, line-by-line breakdown. This lists every cost involved in making the film. Not only are the costs split by individuals, but they may also be further split by when the work is being done, their rate, etc. The full breakdown for The Village is 79 pages long and this is by no means an unusually long budget.

- The topsheet. This summarises each of the line items into broad categories, such as Editing, Costume, Sound, Lighting, etc. Even some headings which appear to be for a single item will be a collection of related costs. For example, the ‘Director’ line will typically include all of the costs involved with the director including their fee, their assistant, their travel, accommodation, trailer, etc. Top sheets are usually one or two pages long.

- The four sections. In the topsheet, all of the costs will be grouped into one of four categories:

- Above The Line (“ATL”). These are the key creatives involved in the movie, including the writer(s), producer(s), director(s) and top few actors.

- Below The Line (“BTL”). This is everyone, and every thing, involved with the filming of the movie that’s not already in the ATL.

- Post-Production. The costs involved with taking the raw footage from the shoot and turning it into a finished movie.

- Other. Costs involved with making the movie which are not covered above. This typically includes insurance, accounting, financing costs, overheads, publicity work carried out on set such as shooting ‘behind the scenes’ footage.

Note: This is a simple summary of a complex topic, and exactly how people create budgets can differ between companies, industries and locations.

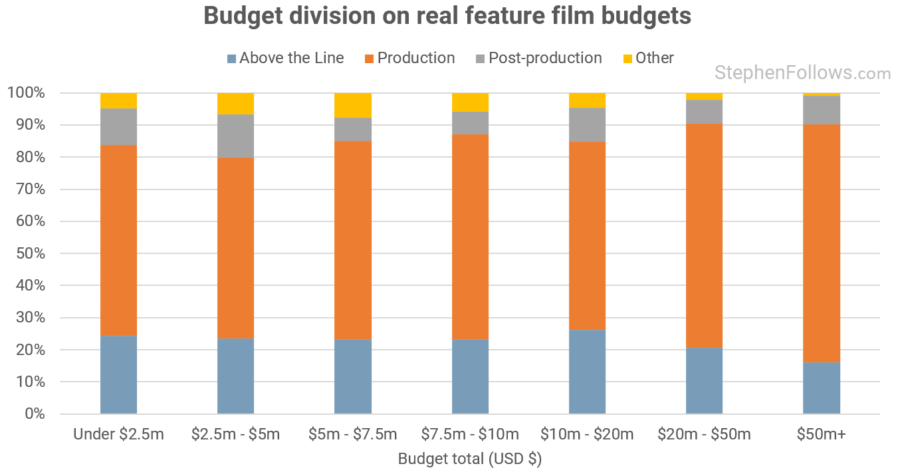

The focus of today’s research is how the allocation of resources changes as a budget’s overall size increases. To measure this, I have combined 107 budgets and calculated what percentage of the total budget is allocated to each category.

Top level changes

Let’s start with the big picture – the four categories of costs.

Given the differences between the types and scales of movies, it’s fascinating that broadly speaking, film budgets share a similar make-up. Above the Line costs account for between 16% and 26% of the total budget, Production is 56% to 74% and Post-production 7% to 13%. Other costs show the biggest variation, at between 1% and 8%.

Let’s look at each of those in a little more detail.

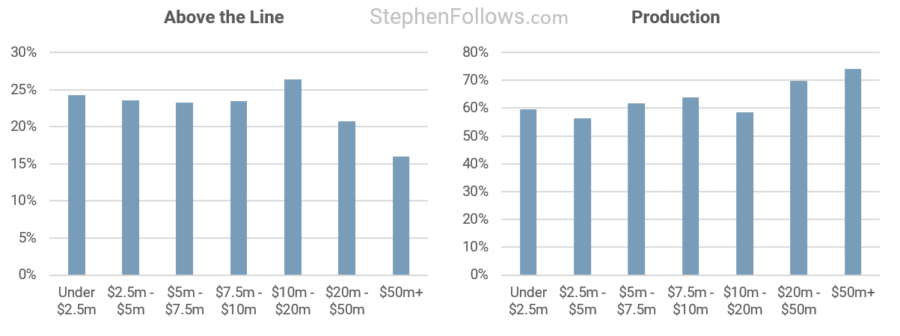

The Above The Line (ATL) costs are fairly static for films under $50m, accounting for just under a quarter of the total cost. The biggest films spend proportionally less on the ATL, although bear in mind that if a $160 million movie spends a quarter of its budget ATL, we’re talking about $40 million being split between a small number of people.

Production costs are similarly flat, at just over half the total cost, until we move into the bigger films when it gets closer to three-quarters of the total budget.

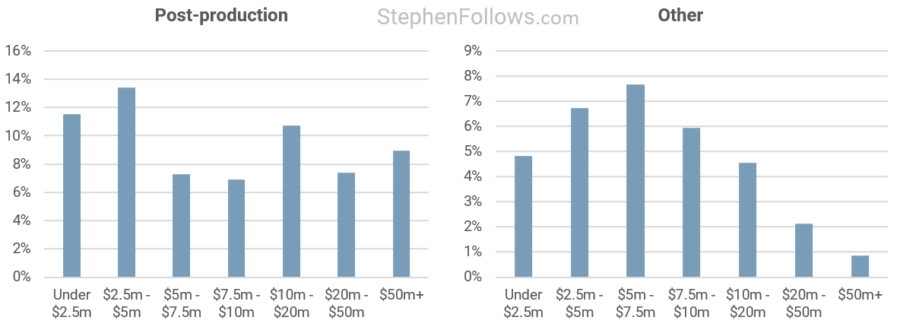

Post-production is relatively the most expensive for the smallest films, with post-production for films over $5m typically being around 7% to 9% of the total budget. How the post-production budget is allocated does vary quite a bit with budget scale (we’ll come back to this shortly).

The ‘Other’ costs vary significantly across the budget ranges. This is due to a combination of historic costs attached to the productions, and variations in project-specific issues like legal costs.

There’s not space to go through every single line item, but I do want to highlight a few interesting departments.

How the ‘Above The Line’ costs change

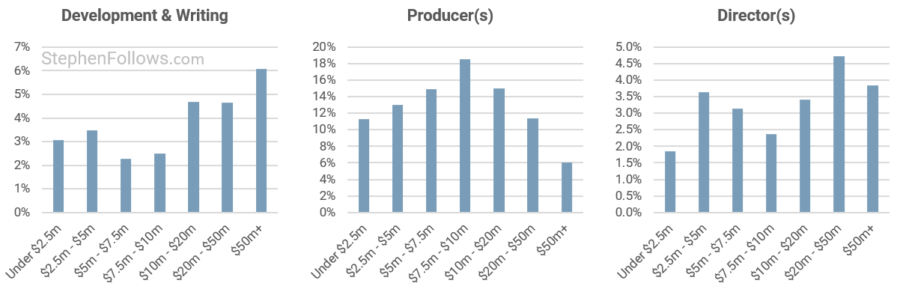

It would be reasonable for a member of the public to believe that the cost of writing a movie would not increase with the budget as it’s still a small number of people typing on a computer. In fact, the costs do increase – considerably so. Films on the biggest budgets spend proportionally twice as much as the smallest films to get their script ready to shoot. This is a mix of:

- Increasing salaries, matching the skill and experience level of the writers.

- Additional development personnel who may help find and secure source material.

- The cost of licencing the source material, such as a book or play.

- The cost of securing the rights to the film franchise. For example, the development budget for Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines comes to almost $20 million as the producers had to buy the rights to the Terminator franchise. They later sold the rights to the producers of the fourth instalment, Terminator Salvation, for $25m.

The cost of producers also rises with budget scale, peaking at 18% of films budgeted between $7.5m and $10m, before dropping again to around 6% for the biggest movies. It’s worth remembering that producers may also be paid in other ways. Their production company may charge a fee, they may also be a writer or director on the project and they are likely to have a share of any profits the film generates.

The cost of the director (and their accompanying staff and unit) also roughly rise with the budget, albeit not consistently. Directors often take on additional roles such as producer or writer. This complicates how their total paycheck would be allocated in the budget. For example, for The Village, M. Night Shyamalan’s total fee was just over $10 million but little of that appeared as a director’s fee. He received $7.2 million for the rights to his script (plus $300,000 for re-writes), $2.5 million for his role as producer (plus $500,000 for his producing overheads) and just $233,384 for directing.

How the Cast costs change

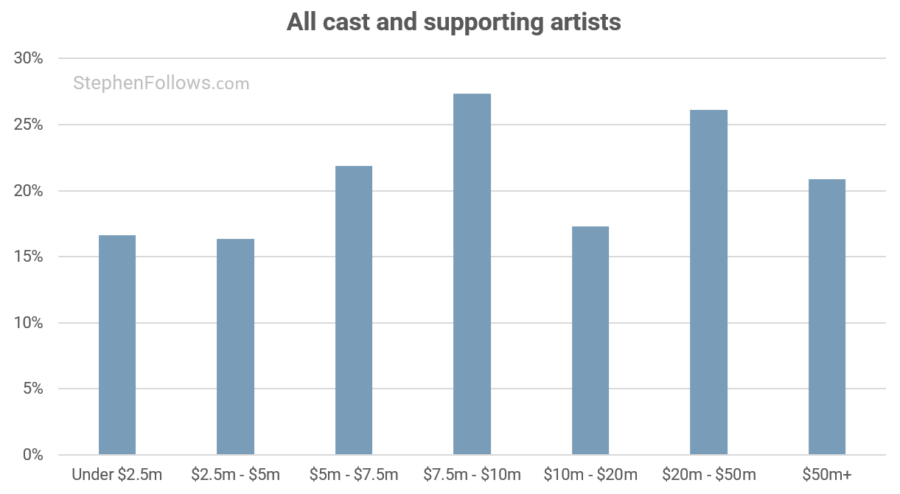

Typically, cast costs are spread across three categories:

- Above The Line cast. These are the major acting names on the production, sometimes called the principals or the ‘marquee names’ as they appear on the cinema marquee above the title of the movie.

- Other cast. In the Production section, below the line, you’ll find all of the other actors who have characters and lines of dialogue. This ranges from the secondary cast right through to bit parts who appear in just one scene.

- Extras, supporting artists and crowd. These are the folk who fill out the background of scenes, providing fighting soldiers, dining patrons or shouting crowds.

Unfortunately, there was little consistency between my budgets as to where to draw the line between each of these three categories. Some budgets just listed “Cast”, some included extras within “Non-Principal Cast”, while others broke down all of the different types. I have combined all the types of casts in the chart below.

How the Production costs change

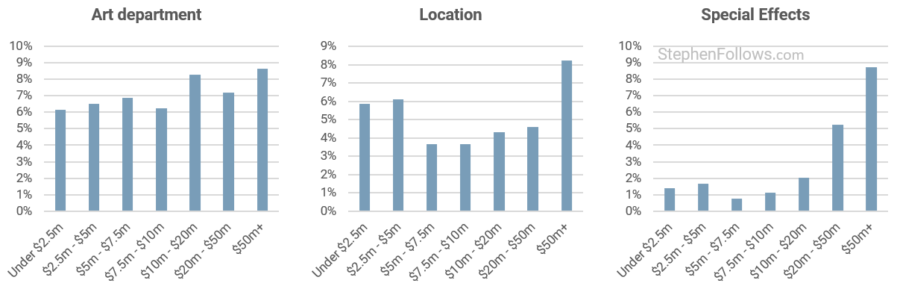

Let’s take a look at the below the line production costs. There are quite a few so I have highlighted a selection to show how they change as budgets increase.

The first group is costs which increase along with the budget. The art department, location costs (including studio space and set builds) and on-set special effects take up a bigger share of the budget as the total cost rises.

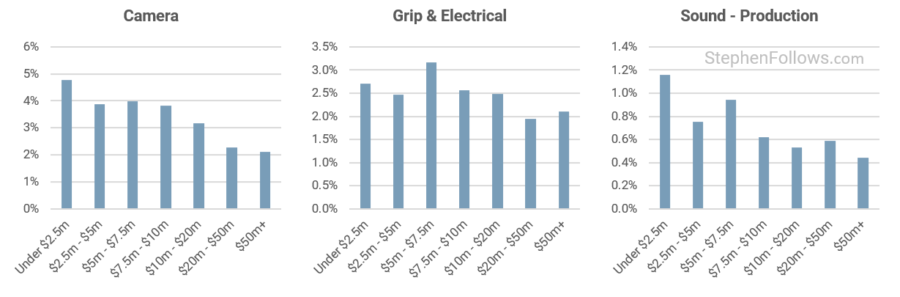

The next group is costs whose relative size shrinks as budgets increase. Remember that the total cost in dollars may still go up, as it’s the percentage of the total budget we’re measuring here.

The camera department goes from being around 5% of the costs of the cheapest films down to just 2% of the most expensive films. Grip and Electrical costs (i.e. lighting) also fall, as does on-set sound.

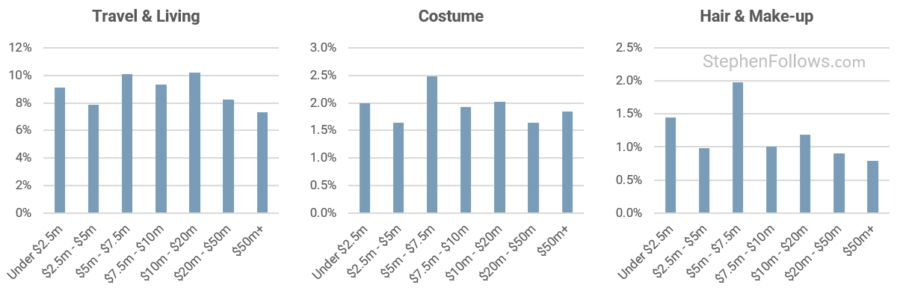

And the final group in below the line production is those whose scale roughly stays the same. Travel and living (covering all transportation, accommodation and catering), costume and hair & make-up all increase loosely in line with the budget’s total cost.

Note: The jump in hair & make-up costs for films costing $5m to $7.5m is a consequence of the films I studied, rather than an industry-wide trend.

How the Post-Production costs change

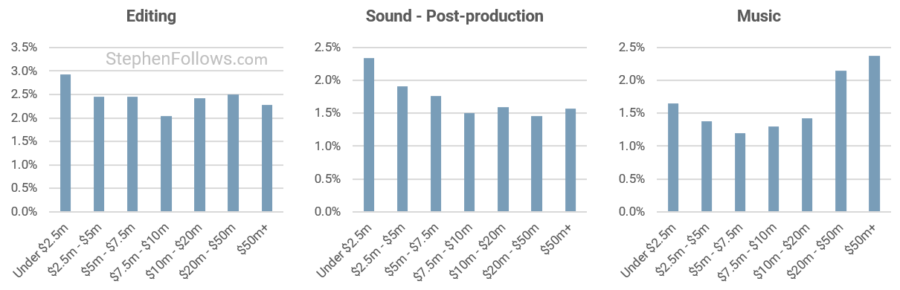

The key parts of post-production (i.e. assembling, editing and finishing the picture and sound elements) shrink slightly, relative to the total cost. The main post-production element which grows with the budget is music. This will be a mix of increasing the cost and scale of the score (i.e. a more expensive composer who is working with a larger set of musicians) and an increase in the use of licensed music tracks from well-known artists.

How the ‘Other’ costs change

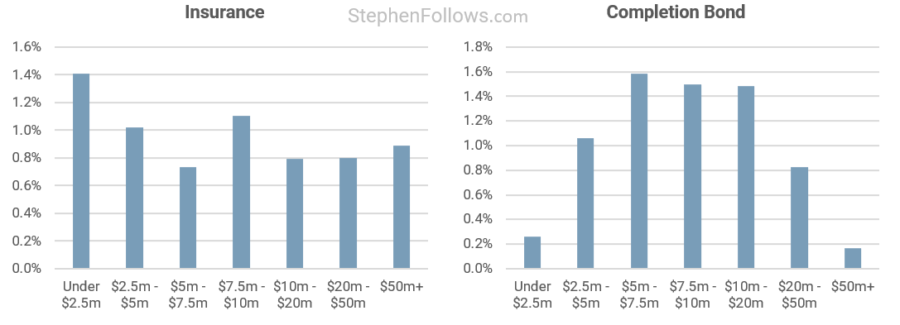

Finally, we come to the last part of the budget top sheet – Other costs. This is grab bag of costs which changes significantly between budgets. The two items I wanted to highlight are both forms of insurance.

The first is the standard insurance coverage which productions need to protect their cast, crew, equipment and locations. This falls as budget increases but is roughly around 1% of the total cost. The actual cost of insurance is often pegged to below the line production costs, rather than the films’ total cost, and so if you’re used to paying a higher percentage than 1% then this could be because it’s being calculated differently to my methods for today’s research.

The second type of insurance is the Completion Bond, which is effectively investors’ insurance. A completion bond company will, for a fee, agree to insure the production in case of a failure to produce a final film. They have hiring and firing rights and will step in if they feel the budget and/or schedule are being missed. They will take action to get the production back on track and, if they fail, they will refund the investors the money they put in.

The very smallest films will struggle to get a completion bond as (a) they don’t have much money and (b) they are inherently more risky productions and so few bond companies will be willing to take on the risk. I’m not entirely sure why completion bond costs seem to decline on the biggest budgets. Maybe a helpful reader in the sector can add a comment or drop me a line to set us straight.

Further reading

If you want to explore these topics in more detail then you may enjoy these past articles:

- How movies make money: $100m+ Hollywood blockbusters

- What’s the average budget of a low or micro-budget film?

- Do filmmakers lie about their budgets?

- Do more film crew members work on-set or in post-production?

Notes

The raw budgets for today’s research came from leaks online and from industry sources.

The raw budgets for today’s research came from leaks online and from industry sources.

The biggest single source (and someone who is happy to be mentioned publicly) is film producer and financier Wayne Godfrey. I am immensely grateful to Wayne for his generosity in sharing the budgets and his patience in waiting the months it took me to be able to turn them into useful findings for the community.

It’s worth noting that although this dataset is not tiny, it cannot stand in for every film ever made. A film’s requirements can differ significantly from one another, meaning that the figures shown above are just averages of this dataset, not rules of thumb or the “right” amount to spend. Line Producers spend their careers building up an understanding of how much things cost and even then will spend time and research building the budget of each new project they work on.

Therefore, today’s research is presented as an aid to new and emerging filmmakers who have no scale of reference for how line items shift as budgets change.

The combining of all this data presented some challenges. Before this project, I was not aware of just how differently budgets can be structured. Almost all fit into the four major sections (above the line, production, post-production and other) but within each there are all manner of approaches. These include how travel, living and transport are accounted for. Sometimes this can be within department budgets, sometimes split into three categories and sometimes combined with each other.

When there were just a few cases of different categories being combined (such as when both the director and producer(s) came under “Director & Producer), where possible I asked the film’s producer to provide a reasonable estimation of how the combined line item should be split.

When there were just a few cases of different categories being combined (such as when both the director and producer(s) came under “Director & Producer), where possible I asked the film’s producer to provide a reasonable estimation of how the combined line item should be split.

The budgets were mostly in US dollars but about a quarter of them had to be converted from local currency. I used historic exchange rates in this conversation, ideally based on the film’s shoot dates but otherwise on the film’s release date.

Not all the money paid to key creatives for their role in a movie will show up in the budget. If they have a participation deal then they will expect to get further payments depending on how well the film performs.

I ignored tax rebate in these budgets. They are normally an important part in calculating the final raw cost to investors but are not useful in this particular article. They threw the figures off considerably as they are listed as a minus cost (in other words a credit rather than a debit), thereby making it look like a department was making money. Tax incentives and credits is a topic I can return to in the future and address properly. In the meantime, here’s a primer of the UK Tax Credit system.

I also removed contingency allocations. This was done partly because some of my budgets were post-completion and therefore did not have any contingency listed but also because the contingency is not, in itself, a cost. It’s a portion of the funding that’s put aside to cover unexpected additional costs or over-spends. Filmmaking is a highly unpredictable and inflexible endeavour in which simple things like minor weather changes can wreak havoc with even the best-managed budget. The contingency is there to be spent on almost any area of costs which needs it (Line Producers are far more careful and judicious than this sounds!)

For the avoidance of doubt, this is true collaboration with been Wayne and myself. No money changed hands, there was no influence on the results and I had full and final cut of the results.

Comments

Dear Stephen,

As always, you do a great job for filmmakers.

Another interesting subject – but probably more difficult to study due to the difficulty of finding relevant data – would be about film promotion and distribution, which is perhaps the most important issue for indie producers, as markets are changing very quickly and as associated strategies are what makes the final success and potential ROI of every movie.

Thank you for your hard work.

Best

Thanks, insightful.

Hope permission was given by all those with their wages specified in the budgets. Otherwise this is a massive data protection/ GDPR breach by Mr. Godfrey, you cannot just disclose such personal details to a third party even for research (or to promote a new business venture)!

Hi John. Fear not, we took care to ensure we were not breaking any laws here. No personal data was given and no individual wages were disclosed.

Even the directors’ fees were listed for the ‘Directors Unit’, rather than the fee paid to the person.

Also, there is an exclusion in GDPR regulations for research. It’s not a total free pass but so long as there’s a “lawful basis for data processing”, the research is “in the public interest” and all necessary care is taken to protect the data, it’s permissible. (There are further restrictions on more sensitive research topics, like health data, but that doesn’t apply here).

Another great article.

Since this article is meant for new and emerging filmmakers, I would love to see an article on structuring the budget for a low budget film. It would be so great to see where successful low budget films put their money.

Thanks so much for doing this! From a project management perspective, this is wonderful historical data and allows me, as a producer, to better budget films, from understanding “where the money typically goes” to having a much more in-depth understanding of risk and contingency funding per budget area. Great stuff!

It will no doubt vary according to genre, but do you have anything on VFX as a percentage of the budget?

Good question. I hope it gets answered.

From my experience – this is very unpredictable with higher budget productions that need to look sharp to be a success. Whereas the lower budget films aspire to do top notch work but can always make it good enough for QC if they run out of funds. QC being a 3rd party that reviews for quality control.

Thank you so much, Stephen Follows! I so appreciate your statistical input. Hopefully, we can start a collective feed hive where all film producers will be invited to contribute anonymous budgets that help make analysis impactful and provide breadcrumbs for emerging Industry pros. Kudos to you!

Should the graphs by category (E.g. Above the line, Production, postproduction and others) match with their breakdown?

E.g. You are saying that the above-the-line costs of a film below a 2.5m budget comprise the 24.5%aprox of the total film costs in the “above-the-line costs” graph. However, if you sum the concepts in the breakdown of the above-the-line costs such as Development and writing 3.1% , Producers 11.2%, Directors 1.9% and All Cast and Supporting Artist 16.5% , you will hace a total of 32.7% .

Dear Stephen,

What a fantastic blog I just stumbled upon. I’m a data and film enthusiast and am very interested in independent film datasets containing features such as budget (even coarse-grained, but of course better if broken-down by line items), genre, duration, production country/ies, whether the film was accepted to a festival, whether it acquired sales representation, whether it won a distribution deal etc.

I know it’s a long shot, but can the datasets on which you base your analyses be shared (even in a redacted/reduced format) or do they form part of your intellectual property. I don’t plan to publish my results but I’m interested in the data for my personal interest; my wife is a film lecturer, film festival programmer and is producing her first film and the data would be massively useful.

Please let me know and keep up the great work!

Regards,

James

Thanks a bundle. I’ve learned here the folly of planning a first-time Indie movie to too small a budget. Reason being there are so many relatively fixed-cost production line-items which have such an impact on the perceived quality of final result that cost cutting would be counter productive.