I have produced films alone and I have produced in partnership with other producers. Personally, I prefer the latter.

I have produced films alone and I have produced in partnership with other producers. Personally, I prefer the latter.

Producing a movie is a big undertaking and so it’s good to have people to share the load and journey with. Plus the film gets to benefit from multiple people’s strengths, passion and contacts.

Recently, I was chatting to a producer who has the opposite view. They prefer to have the sole producing responsibilities rest on their shoulders as it allows them to keep the film on track: one vision with one leader.

So I thought it would be interesting to look at what the data reveals. We can’t objectively test ‘which is best’, but we can look at one facet of the question – are films produced by one producer more successful than those made by teams?

Let’s start by looking at how many people produce movies alone, and then move on to looking at how it correlates with financial performance.

Note: We’re looking at people receiving a full ‘Producer’ credit, not Execs, Associates, etc. More on that at the end of the article.

How many films are produced by just one producer?

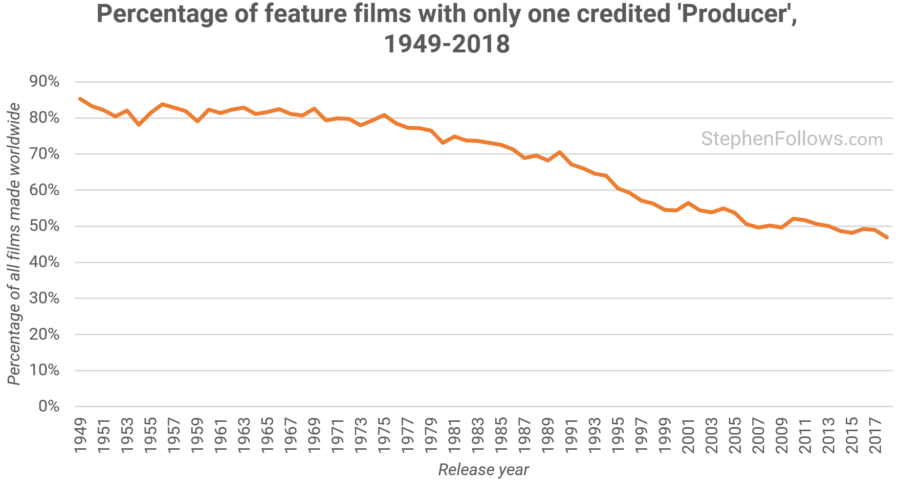

Over the past fifty years, the solo approach to producing has been in decline.

Four out of five movies made in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s had just one credited Producer. This fell fairly consistently and so far in the 2010s, it’s just half of movies made.

Do solo-produced movies make more money?

Do solo-produced movies make more money?

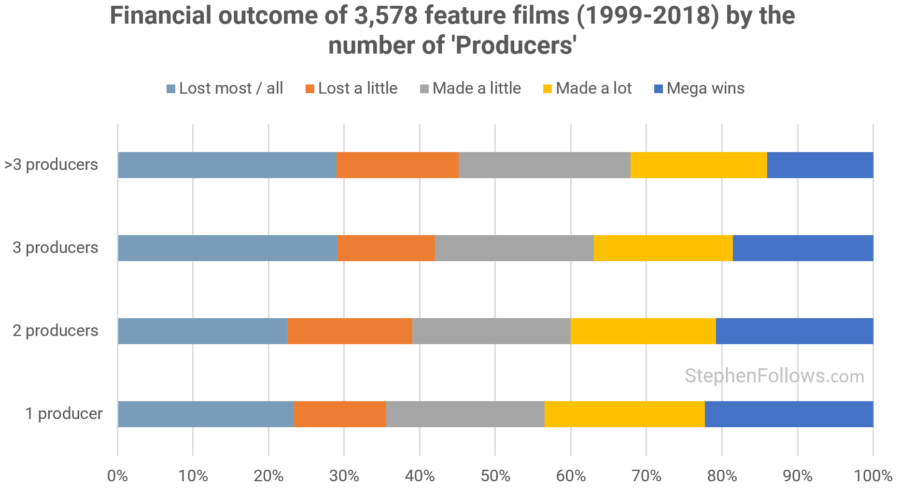

Next, we need to bring in financial data on 3,578 feature films made between 1999 and 2018 to assess their performance (there are more details on this in the Notes section).

Next, we need to bring in financial data on 3,578 feature films made between 1999 and 2018 to assess their performance (there are more details on this in the Notes section).

Taking into account all costs and income it is possible to calculate the likely financial return for each movie. I have categorised them into the following five outcomes:

- Lost most / all – Returned below 50% of the production budget.

- Lost a little – Returned between 50% and 100% of the budget.

- Made a little – The film recouped its budget and earned additional profit up to its original budget.

- Made a lot – Returned a profit of between one and three times its budget.

- Mega wins – The film’s profit was more than three times its original budget.

This reveals a result I was not expecting – solo-produced movies perform slightly better than those with multiple ‘Producers’.

Movies with one or two producers were the least lightly to completely flop, and at the other end of the spectrum, the ‘mega wins’ were more likely to have just one ‘Producer’.

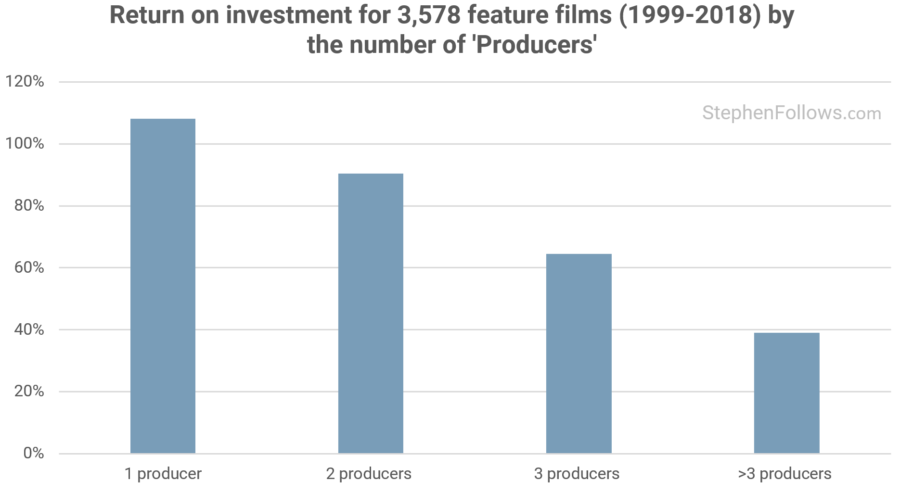

There is a little more to be said on the topic as the chart above is hiding one element of film investment – the power-law of financial returns.

Put simply, the top few films earn massively more than all the others put together. In the case of this dataset, half of all the profits generated were from just 2% of the films. Therefore, as films with one Producer perform marginally better in the ‘Mega wins’ category (i.e. those returning more than three times their production budget) it is perhaps not surprising that such films hugely out-perform those with additional producers.

Let’s imagine we group all 3,578 films into four index funds – those with one Producer, those with two, those with three and those with four or more Producers. You invest $100 into each of the funds – how would your investment perform?

The ‘One Producer’ fund would return 108% – not a bad return in today’s financial climate. However, the other three funds would not pay back your original investment in full, with the ‘Four-or-More Producers’ fund returning less than half.

Does this mean that all teams of producers should start re-creating Highlander for the sake of their movies? Beyond how much fun that sounds, no, I don’t recommend it.

Partly because this is not a massive result and therefore is likely to be overpowered by bigger factors on each individual movie. Secondly, we don’t know why this is happening. We can spot the correlation but not the causation.

Each movie is unique and so there will be cases where the data-driven ‘average’ answer does not apply. Producing a movie has two aspects: 1) learning the rules, and 2) acquiring the wisdom/experience/awareness to know when to break them.

Further reading

If you want to learn more about producer credits then you may enjoy these past articles:

- What percentage of film producers are women?

- On average, how many films does a producer produce?

- How old are Hollywood film producers?

- How many movie producers does a film need?

Notes

Data for the number of producer credits on each movie came from my database of movies, built from a number of sources including IMDb, The Numbers / Opus Data and Wikipedia.

Data for the number of producer credits on each movie came from my database of movies, built from a number of sources including IMDb, The Numbers / Opus Data and Wikipedia.

The financial data comes from The Numbers’ financial database. This takes into account all full financial details, including North American (i.e. “domestic”) and international box office, video sales and rentals, TV and ancillary revenue to calculate the likely profit margin for the producers, after all revenue and expenses. The financial figures come from a variety of sources, including people directly connected to the films, verified third-party data and computation models based on partial data and industry norms. It is possible that one or two of the individual figures are different from the predictions, though en masse I am confident of the larger picture.

It’s worth noting that today’s figures should not be used to infer the overall profitability of films more broadly. The dataset has been created based on available data and while this works for answering our core question, it cannot be read as an objective measure of sector averages.

There is no comparative advantage or disadvantage to increasing the number of Executive Producers. This is likely to be due to the fact that people are given Executive Producer credits for a variety of reasons, ranging from being heavily involved in the creation or sale of the movie through to being a silent investor.

Epilogue

Producing credits are interesting as they give us a window into an otherwise opaque part of the filmmaking process. They are not regulated by unions (the way that directing or writing credits are) and there are a number of types of producing credits which each production is free to interpret. Therefore they can often reveal power dynamics and hierarchies.

Producing credits are interesting as they give us a window into an otherwise opaque part of the filmmaking process. They are not regulated by unions (the way that directing or writing credits are) and there are a number of types of producing credits which each production is free to interpret. Therefore they can often reveal power dynamics and hierarchies.

For example, Kevin Feige is the only credited Producer on all Marvel films (well, not the Sony/Marvel hybrids but even in those cases there are only two Producers – Kevin Feige and Amy Pascal). On Avengers: Endgame, there were twelve people listed with producing credits other than Producer, including Executive Producers, Co-producers, an Associate Producer and a Line Producer.

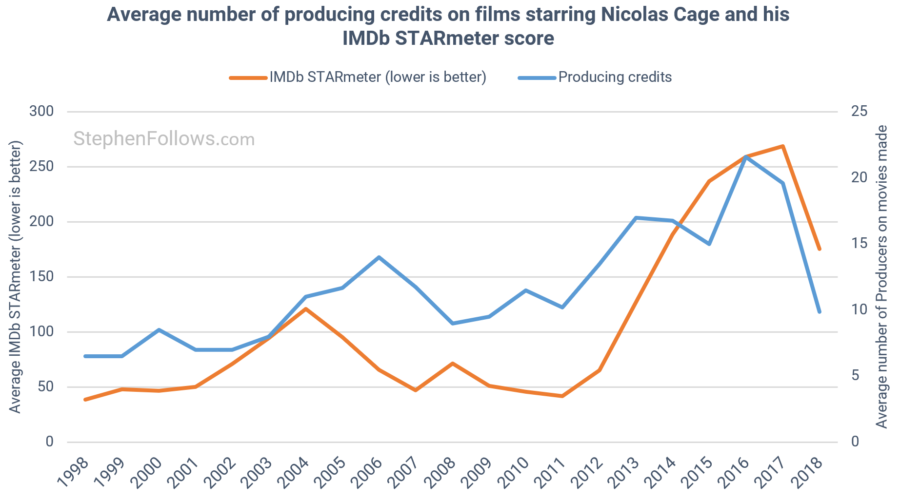

I will leave you with this fun nugget: Nicolas Cage’s career seems to be inversely correlated with the number of people who have received producing credits on his movies. The chart below shows the average number of Producers on each of his movies and the average IMDb STARmeter for each year, where the most famous person in the world at any one time would have a STARmeter score of 1.

I’m not quite sure what to make of this. Suggestions in the comments, please!

Comments

The Nicolas Cage data seems to correlate with the recent NYTimes profile. That is, he’s a very quirky actor in many ways and might therefore be best used by an individual with insight into his sometimes eccentric choices. A team of producers seems less likely to have this insight collectively.

I’m guessing the upwards trend in producers has a lot to do with the transition from developed-in-house studio films to the rise in numbers of indie films and coproductions, where multiple sources of financing and tax incentives come with credit requirements and, on tightly budgeted indies, credits are often awarded in lieu of fees, especially for producers, which, as you note, are not restricted by guild contracts, etc. In the case of poor Mr Cage, the plethora of producers is usually indicative of projects that passed through a number of hands before getting to production.

“Put simply, the top few films earn massively more than all the others put together. In the case of this dataset, half of all the profits generated were from just 2% of the films”

Wonder how this would look if you removed the top 2% ? Would that make for a more accurate picture or not? Honestly unsure.

As always great article.

Hi Robert. Good thought.

Firstly, I’d say that there is no “accurate” picture as all the crunching involves some subjectivity and relates to what you want to know. If you have an index fund then the top 2% are extremely relevant, whereas if you’re picking just one or two films to invest in, then they may be a dangerous distraction.

I just checked and removing the top 2& of earners (by raw dollars) massively reduces the overall returns but keeps the pattern exactly the same. Removing the top 2% by ROI has a negligible effect (because the ones with crazy high ROI tend to be tiny films by their very nature).

Interesting and great articles.

I am a film practitioner from China. I often read your articles, which benefits me a lot. Thanks!