How does the use of the terms 'cinematographer' and 'director of photography' differ?

I looked at the credit of 4,000 top-grossing films reveals when and where the titles 'cinematographer' and 'director of photography' appear, and what that tells us about style, genre, and convention

When I was starting out in film, I always heard the head of the camera department being referred to as either "DoP" (pronounced dee-oh-pea) or "DP" (pronounced dee-pea), both of which are short for director of photography. As I met more filmmakers, I learned that the same role is often called the cinematographer (pronounced... well, the way it's written).

Today, I thought I'd take a look at these two job titles and try to make sense of where each is used.

What is a cinematographer / director of photography?

In most real-world situations, the two job titles are interchangeable. Simply put, this person is responsible for crafting the film's visual style, or 'look'. They report directly to the director and have a large number of people answering to them. They run the camera department and also manage the gaffer (who runs the lighting department) and the grips (who are responsible for moving the camera on dollies, cranes, rigs, gibs, etc).

Whilst their work may be most apparent during the shoot, it actually starts in pre-production, when they will be working with the director to plan the look, hiring their team and managing decisions over what equipment to use. And after the shoot is over they will often be included in the grade (the post-production process which tweaks the look and colour of the final film).

So, you may ask, why have both terms? The historical reason is that many national film industries evolved independently from each other and so different terms developed for similar roles. The modern-day reason is that some of the people doing the job want to be credited as cinematographer while others prefer to be called the director of photography. It's this that I'm studying today. It's mostly a matter of fashion and convention, which makes it a fascinating thing to measure, as we can see how states change in different parts of the industry.

A few years ago I used my dataset of the top 200 US-grossing films of each year of the past two decades (i.e. 4,000 films released between 1997 and 2016) and looked at the credits given to the cinematographer / DoP. Over this period, 1,092 different people received a cinematography credit on the films in my dataset.

Which term is used more widely?

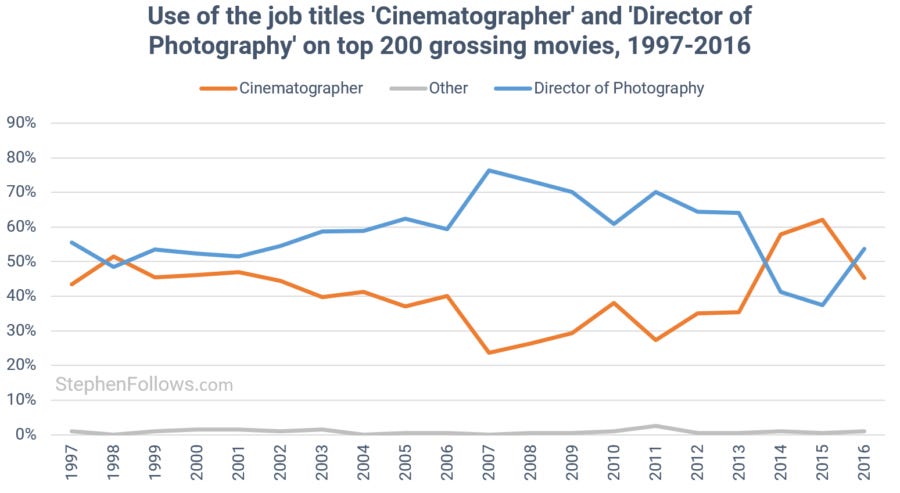

The short answer is that director of photography is more commonly used. 58.4% of films released over the past two decades use the term, compared with 40.8% opting for cinematographer. 0.8% used other terms, including "shot by" (Sin City), "lighting cameraman" (Eyes Wide Shut), "director of cinematography" (Tees Maar Khan) and "photographed by" (Enemy).

The fashion for one term over another does seem to be cyclical, with cinematographer overtaking director of photography in the late 1990s and again in the early 2010s.

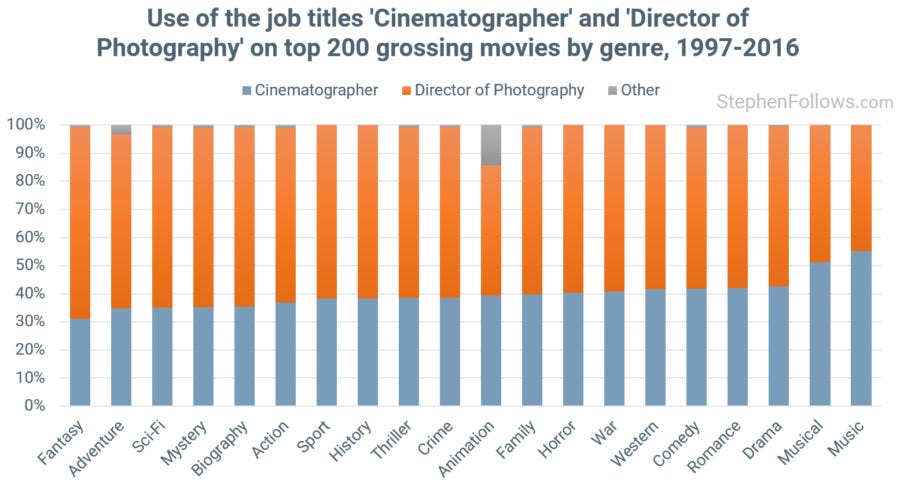

When we look at the genre of movies using each term, it seems that movies which rely on big, expensive visuals (i.e. fantasy, adventure and sci-fi movies) are much more likely to favour 'director of photography', while smaller, more human-interest genres (i.e. romance, drama and music-based movies) opt more often for 'cinematographer'.

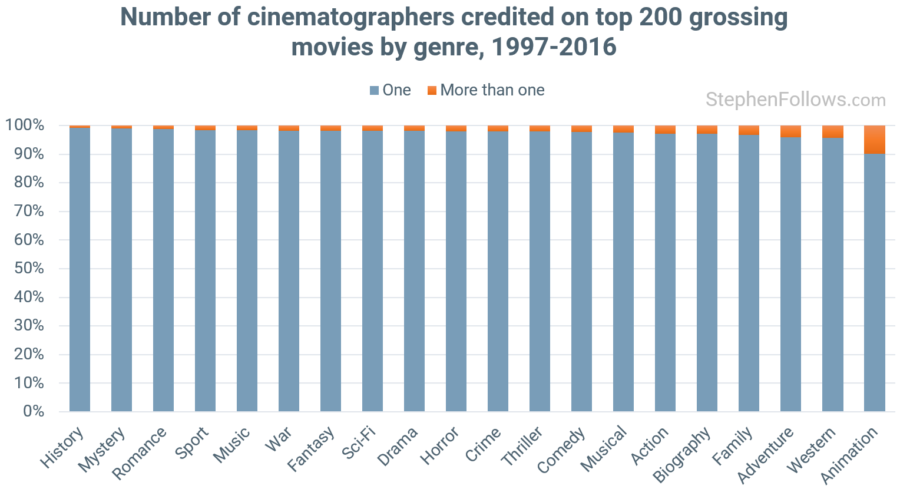

In the chart above, you may notice that animation is the genre with the largest percentage of 'other' terms. That's because the traditional role of a cinematographer is more varied on animation-based movies. The process of creating the visual look of a live-action film differs significantly from that of a 2D hand-drawn animated movie, which again differs from a 3D computer-generated production. In fact, only 52% of animated movies in my dataset even listed a cinematographer of any type.

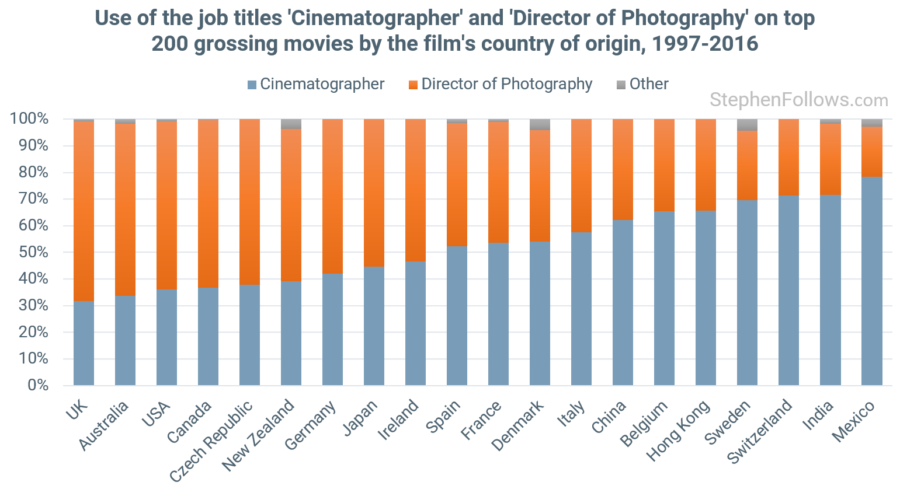

An oft-repeated line about the difference between the two roles is that it has to do with the nationality of the crews. I looked at the countries of origin for the movies and, as shown below, the UK seems to be where director of photography is most commonly used.

It should be noted that this study is only of the top 200 US grossing movies, and so if we wanted to do a thorough investigation of how the terms change between countries we'd need to study all movies made in each country, not just the ones which performed well in US cinemas.

Note: For readability, in the rest of the article I'm going to use the phrase 'cinematographer' to refer to people credited both with cinematographers and director of photography.

How many cinematographers shoot multiple movies?

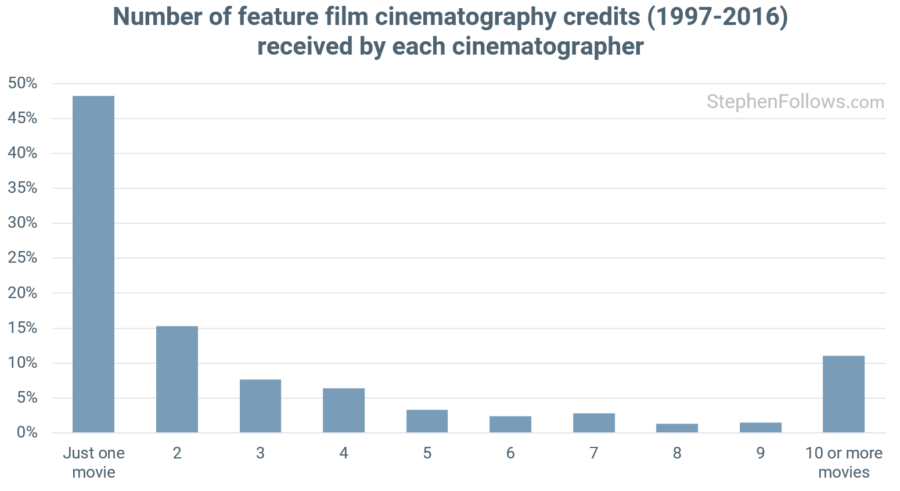

A few weeks ago, I looked at the most prolific crew members on top-grossing movies, including cinematographers. Roger Deakins came top, with 29 movies credits as cinematographer over the two decades studied, followed by Dean Semler (26 movies in the study), Robert Elswit (26), Andrew Dunn (26), Oliver Wood (24) and Don Burgess (24). But how typical are these prolific cinematographers?

Only 1.3% of cinematographers in my study were credited: an average of one movie a year (i.e. at least twenty credits over the twenty-year period). Fewer than one in five cinematographers have shot more than five movies over these two decades.

Do cinematographers play well with other cinematographers?

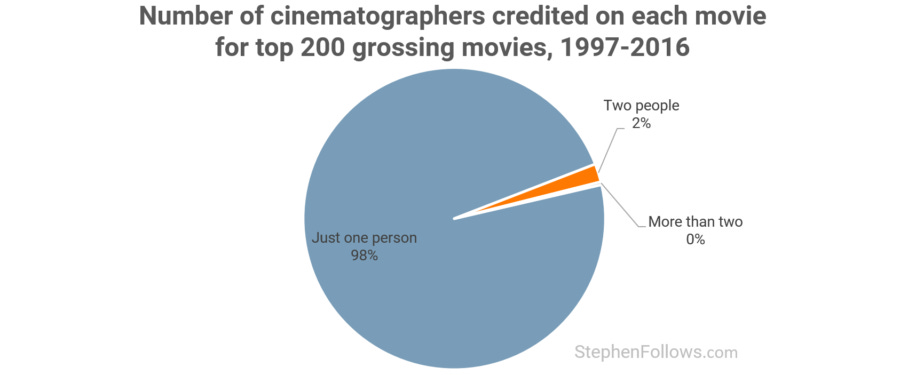

I've previously shown how the role of cinematographer is the least likely of all major creative roles on a movie to be shared among two or more people - even less so than the role of director.

Only 2% of movies in my dataset had two cinematographers (such as Bollywood movie Ra.One which credits both a director of photography and a co-director of photography) and only 12 movies (that's 0.3% of the whole dataset) listed three or more.

So what are these rare movies which list multiple cinematographers? Mostly animations (such as Chicken Run, which has two directors of photography and three lighting cameramen) and portmanteau movies (such as Paris, je t'aime and Movie 43, which have 17 and 9 respectively).

It's a man's world

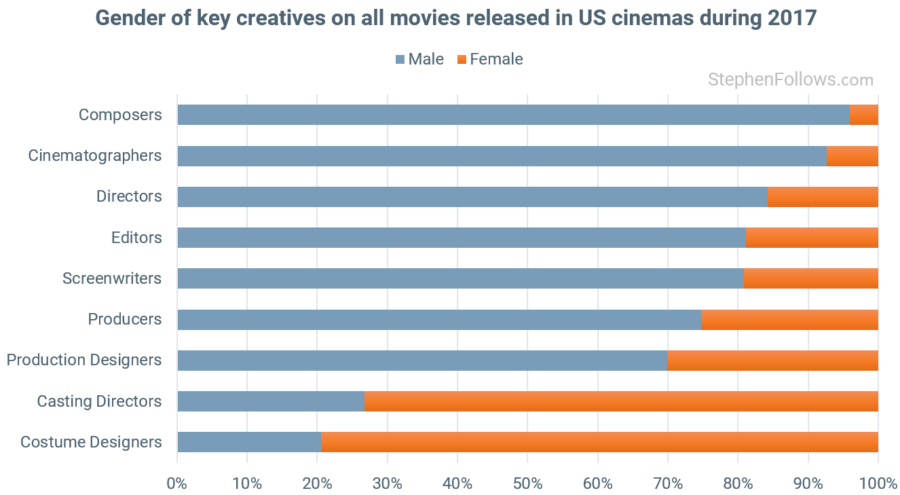

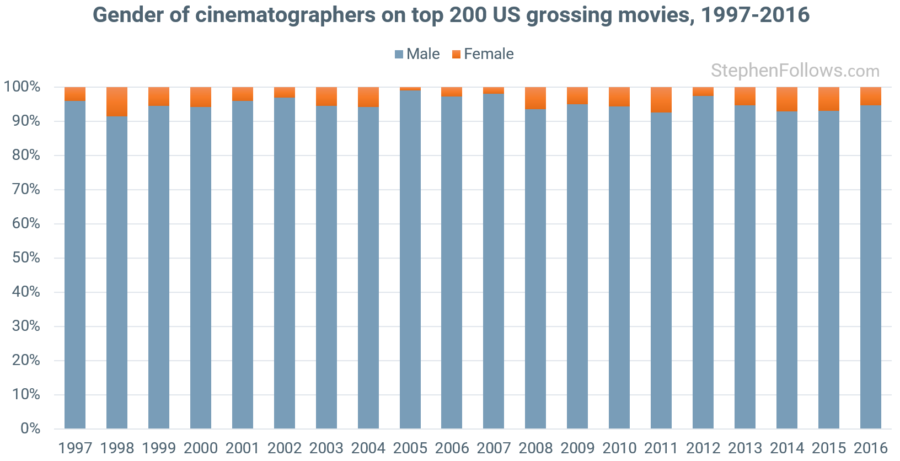

Today's article focuses on the different terms used to describe the job, but it's not possible to cover cinematography and ignore the gender inequity. Of all the major creative roles, cinematographers have the second worse female representation, only faring better than composers.

This has been a common thread for as long as the role has existed. It wasn't until 1980 that the first woman was accepted into the American Society of Cinematographers (Brianne Murphy) and the first woman to receive an Oscar nomination for Best Cinematography did so this year! Rachel Morrison earned her nomination for her work shooting Mudbound. Over the twenty years, only 45 of the 1,091 people I studied were female - that's just 4%.

Notes

The data for today’s research came from IMDb, Wikipedia and The Numbers. I have used the US box office as the criteria because the data is more reliable (and complete) than that of the worldwide box office. I focused on the top 200 grossing films, rather than all films made or all films released, in order to be able to compare like with like.

I used biographical information to determine the gender of cinematographers, with only one person out of 1,092 people eluding me. It’s worth reiterating that I was just looking at movies. This means that a cinematographer could have a very prolific career within TV, music videos, adverts, etc and yet not rank too highly within today’s charts.

Epilogue

The aim of today's research is not to decide which term is correct, but rather just to observe what has been happening in recent decades.

In researching this piece, I reached out to a number of cinematographers in the hope of finding a common consensus on the use of the terms. After all my conversations, I concluded that there isn't any industry-wide agreement. I am sure many people will have thoughts on the debate between the two titles, so I'd welcome these in the comments below.

This is great!! I love charts to explain stuff like this ✨️