Do male and female critics judge films differently?

Last week, a row erupted over a film review in Variety of Carey Mulligan's new movie Promising Young Woman.

In an interview for The New York Times, Mulligan discussed her frustration of reading character descriptions along the lines of "Beautiful but doesn’t know it", and with the way movies present women as sexual objects for the gratification of men. As a case in point, she highlighted a review of her new movie in Variety by Dennis Harvey which included the following:

Mulligan, a fine actress, seems a bit of an odd choice as this admittedly many-layered apparent femme fatale – Margot Robbie is a producer here, and one can (perhaps too easily) imagine the role might once have been intended for her. Whereas with this star, Cassie wears her pickup-bait gear like bad drag; even her long blonde hair seems a put-on.

Carey Mulligan told The Times:

He was basically saying that I wasn’t hot enough.... It drove me so crazy. I was like, ‘Really? For this film, you’re going to write something that is so transparent? Now? In 2020?’ I just couldn’t believe it.

This led to Variety adding an editor's note to the review, apologising for the "insensitive language and insinuation". A few days later, the review's author spoke to The Guardian, saying:

I’m a 60-year-old gay man. I don’t actually go around dwelling on the comparative hotnesses of young actresses, let alone writing about that... And while Carey Mulligan is certainly entitled to interpret the review however she likes, her projection of it suggesting she’s ‘not hot enough’ is, to me, just bizarre. I’m sorry she feels that way. But I’m also sorry that’s a conclusion she would jump to, because it’s quite a leap.

I am not seeking to add commentary to this particular fracas, nor to litigate who's right about what. But I do want to look at Mulligan's initial point about the male gaze, specifically in relation to film criticism.

The 'male gaze' is a complex topic which cannot be 'solved' using data. We can't measure bias directly but we can answer the following related questions:

What percentage of film critics are women?

Do female critics cover the same films as their male peers?

Do female critics like different movies to their male peers?

To be clear, these are not the main questions at the heart of the debate over male gaze, but hopefully answering them will aid the conversation. To do so, I built up a database of 181,927 professional film reviews, covering 7,312 movies released over the past two decades. I then found the gender of the critics via their biographies (more on the methodology in the Notes section at the end) and to provide a comparison, I also gathered IMDb audience ratings on those same movies, split by gender.

1. What percentage of film critics are women?

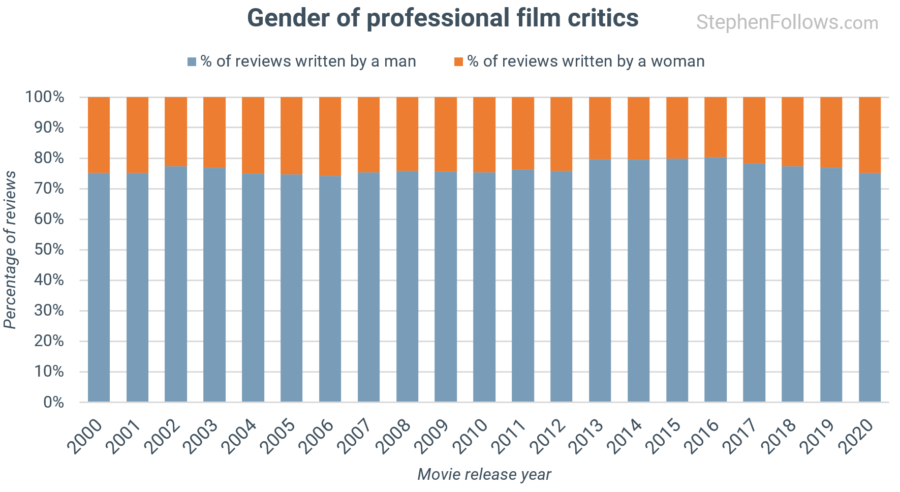

Over the past 21 years, 23.2% of professional film reviews were written by a woman. In 2000, women wrote 24.8% of reviews and by 2020 the figure stood at an almost-identical 24.9%. The best year for female representation was 2006 (25.8%) and the worst was 2016 (19.7%).

Given the gender shifts which have taken place elsewhere in the industry over these two decades, it's quite surprising to see such a static result.

2. Do female critics cover the same films as as their male peers?

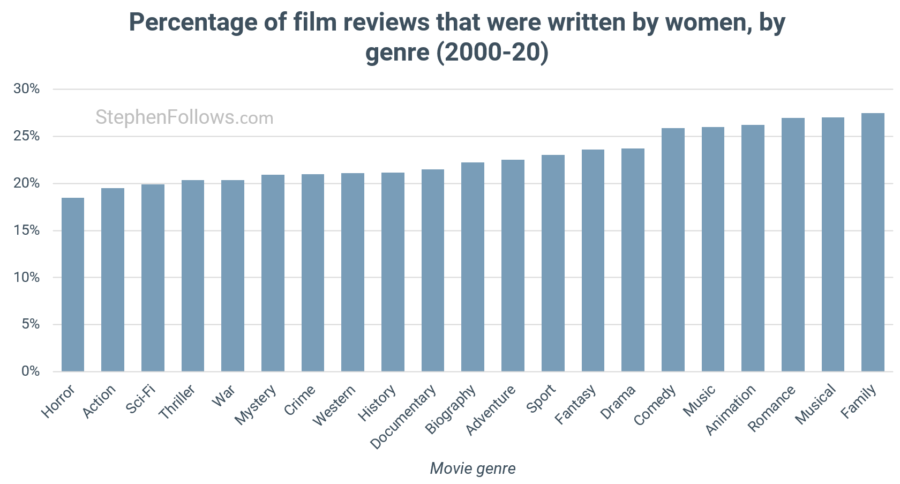

By splitting the films by genre we can look at how the gender of critics changes between genres.

Female critics are more likely to review romances (27% of reviews are written by women), musicals (27%) or family-orientated (27.5%) movies. Men outnumber women most in reviews of horror (18.5% are penned by women), action (19.5%) and sci-fi (19.9%) movies.

The genres which had the highest percentage of female critics largely fall into the stereotypes of "female-orientated" movies. Interestingly, they heavily overlap with the gender split of IMDb users. The chart below shows the percentage of film reviews and IMDb audience votes which come from women, with a trendline in blue.

I don't know enough about how reviews are assigned to critics within a publication so I would be keen to hear from people with experience in the comments. To what degree do critics get to chose which films they review? Is genre a factor when picking which of the possible reviewers will be chosen for each film?

3. Do female critics like different movies to their male peers?

We can using ratings from our two different datasets to get a sense of whether men and women rate films differently.

The chart below shows the average ratings given by IMDb users and professional film critics, split by genre and gender. Overall, female IMDb users rate all genres slightly higher than their male counterparts, but film critics largely agree, no matter the gender of the critic. In both cases, there is a broad consensus on the relative quality of genre, i.e. everyone put documentary first and horror last.

We can simplify the chart above to show more clearly the relative differences between genders. The chart below is looking at the same data but focuses on the difference between how men and women rated the same movies. The chart shows the percentage difference between female and male scores, with a positive number indicating that women rated the movies higher and a negative value showing that men rated it higher.

This indicates that, on average at least, the gender of film critics is of little to no importance when looking at the rating they assign to a movie.

We must remember that film criticism is much more than just a numerical rating. Different reviewers may highlight different aspects of a movie, provide differing perspectives and express their views, well, differently.

Notes

The data for today’s research came from a number of places, principally Metacritic, Rotten Tomatoes, IMDb and Wikipedia. The criteria for inclusion into the dataset was all feature films released in North America between 1st January 2000 and 31st December 2020, which had a Metascore, at least 10 professional film reviews, at least 300 user votes from male IMDb users and at least 300 votes from female IMDb users.

To determine a critic's gender, I used publicly available data, pronouns (such as in biographies) and first name analysis (i.e. if 99% of people called Daniel are male then I have regarded every Daniel with an unknown gender as male). I appreciate that this research takes no account of gender fluidity or other forms of self-identification. That’s not a conscious choice but rather a consequence of doing research at this scale. If anyone can suggest a way of taking this on board in the research process then I am very keen to hear it. Please drop me a line and we can talk it through.

If there was anyone for whom I could not reliably determine a gender, then they were not included in the charts which show a percentage split. These "unknown" people wrote just 1.7% of the reviews I studied. Although this is not ideal, I have no reason to think that these people skew towards one gender over another.

Finally, I have tried to be respectful to all in my choice of language when discussing gender and identity. If I’ve misspoken somewhere, drop me a line and I’ll fix it. I aim to use the words "men" and “women” where possible as it relates to identity, not biological sex. The only exception is where it would be grammatically incorrect to do so – i.e. both “woman” and “female” are nouns but only “female” is an adjective and a modifier (i.e. “female critic” is correct while “woman critic” is not).

Epilogue

Last year I studied whether certain publications of reviewers are harsher on big-budget movies than they are to smaller productions. I ended with a quick anecdote about the subjective nature of film criticism. It's actually more relevant to today's topic than it was to the budget correlations so I think bears repeating here.

A few years ago, I was disappointed to see a reviewer for a major publication receiving public taunting for not liking Deadpool 2. She had tweeted ahead of the film that she was dreading the upcoming press screening and was probably not going to like the film. Using screenshots of her tweet and her resulting poor review, online comments flooded in complaining that she was biased and the review should be taken down.

It could be argued that she was the wrong journalist to be assigned to the role, although even that is debatable. Should movies only be reviewed by people who expect to like the movie? In either case, she was not at fault for disliking a movie she wouldn’t choose to watch in her personal life. I’m sure each critic has their own experiences like this and I only single this one case out as it has stuck with me. The anger and cries for retribution were way out of whack with someone not liking a movie.

By its very nature, film criticism is subjective because (a) art can’t have a single objective verdict; and (b) that’s the point – you want to learn someone’s perspective. To me, this seems self-evident. And yet, so many of the public comments added to film reviews and on Twitter are based on the premise that film reviewers could be reaching a single universal objective truth if they weren’t so damned lazy / biased / female.

---

On a wider note, the idea of gendered movie tastes is exacerbated by the feedback loop of film development. If a certain genre has historically attracted a large audience from one gender then future productions will be encouraged to lean into this skew, further entrenching the gender divide.

This means that as fixed ideas of gender and gender tastes are being challenged, it could be that there is an underserved audience for certain types of films. Female-focused sci-fi or male-focused romance films could be the next big thing. Historically, Hollywood has been massively risk-averse and prized conformity over being right, so it's perhaps not surprising that we see the same patterns prevail.

To put on my optimist hat briefly (it's rather dusty from underuse but should still work), perhaps the nature of SVOD will help. It's easier and cheaper to try new ideas out and to get lots of reliable data on their performance. So if you hear of a show which challenges a norm you don't like - watch it! And if you discover an indie film which is right up your alley - buy/ rent it!

We vote with our attention and wallets, and as the industry is in a greater state of flux than it has been for many decades, now is the time to challenge old norms and set new ones.