Last week I was teaching a group of early-stage filmmakers and the topic of running time came up.

Filmmakers often feel limited by the demands on them to make shorter movies. The indie film market doesn't favour longer movies (partly because cinemas hate long movies) and due to the fact that a longer running time typically means a higher budget (data on that here). And yet a shorter running time gives less time to develop characters, stories and deliver the visual and emotional journeys the director has in mind.

The filmmakers I was speaking with cited countless examples of longer movies and I instinctively said that they may get to make longer movies as their careers progress. They requested evidence and I couldn't back up my hunch. From past research, I knew that the average movie in cinemas comes in at 96.5 minutes and that just 5.8% of movies are over 140 minutes long. I knew that many of the longest films come from established directors such as James Cameron, Peter Jackson, Spike Lee, Oliver Stone and Steven Spielberg but the plural of 'anecdote' is not 'data'! I did not have hard numbers.

Feeling a mix of foolish (that I'd made an unsubstantiated claim) and pride (students thinking critically is exactly what I was after), I resolved to explore the data.

I built a dataset of all feature films made between 1949 and 2020 (282,459 films in total), studying their running time and what stage in the director's career they represented. There is more data on my methodology and criteria at the end of the article.

The connection between a director's experience and running time

Let's start by answering the question directly, and then digging a little deeper into the numbers to discover more.

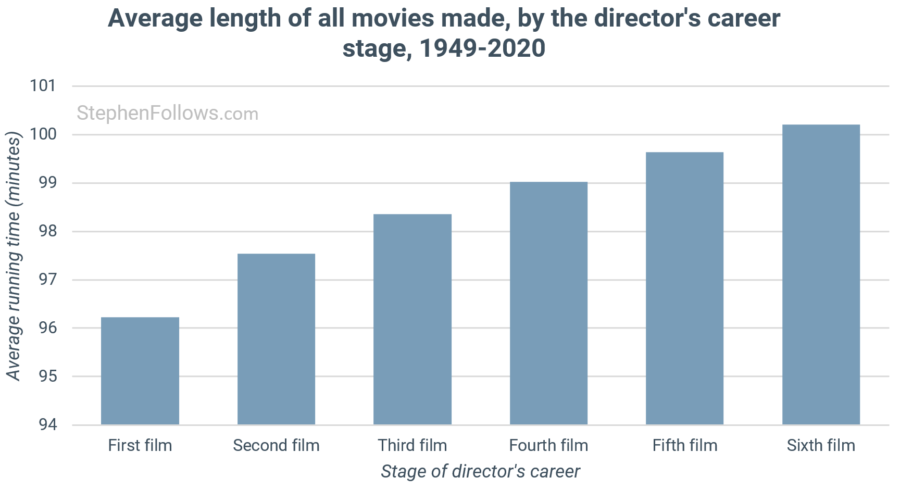

It turns out that, yes, experienced directors do tend to make longer films than first-timers. The average runtime of a film by a first-time film director was 96.2 minutes, compared to 100.2 minutes for a film directed by a director with five previous films under their belt.

How recent is this trend?

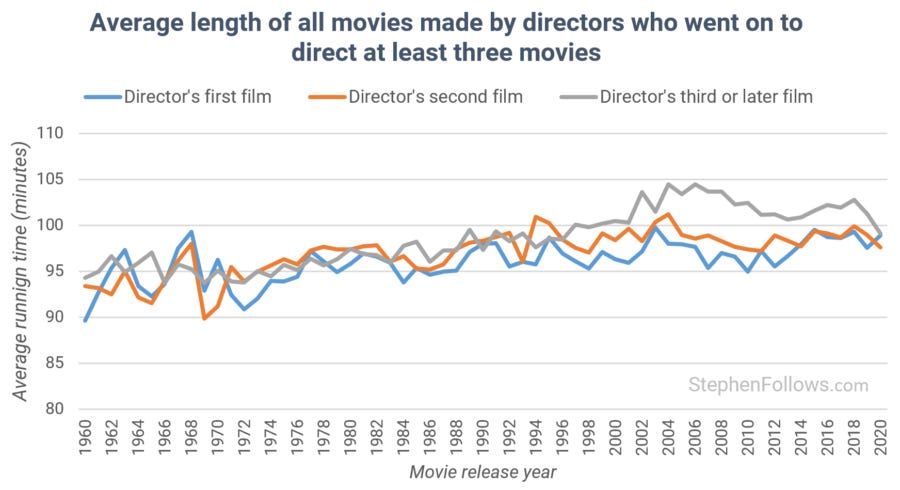

As we dig deeper it's worth noting that movies are broadly getting longer. In 1950 the average movie was 90.7 minutes long, whereas by 2018 it was 10% longer, at 99.3 minutes.

This means we need to be careful to take this into account. Hypothetically, if movies all got exactly 1% longer each year then all second, third and fourth movies would automatically also be longer, given that they have to come after a director's first movie.

Therefore, the chart below groups movies by their release year, and assigns each movie one of three states - if it's a "first movie", a "second movie" or "third or later movie". This reveals that much of the discrepancy between the running time of our three types of movies has come about in the past two decades.

This recent de-synchronisation could be due to a number of factors, including:

Technological changes - Digital cameras and computer-based editing make longer movies cheaper and easier to make.

Industry changes - There could have been an evolution in the power of the director to affect the pressure on them.

More movies - A greater number of independent films being made.

More data - Better reporting of movie data, thanks to the rise of internet databases.

Not all movies are the same

By subdividing the films by genre we can see that this effect is not universal.

Using the Pearson coefficient we can measure the level of correlation between the running time and the experience of its director for each genre. A score of positive one would indicate they are completely positively correlated, zero means no connection and minus one means they are negatively correlated.

As the chart below reveals, all but a handful of genres show a very strong positive correlation.

Some readers may prefer to have the same data displayed in a different form, as I know Pearson Coefficients are not typically taught in film school. Below are the three genres which have the strongest positive correlation between the two factors - sci-fi, drama and thriller.

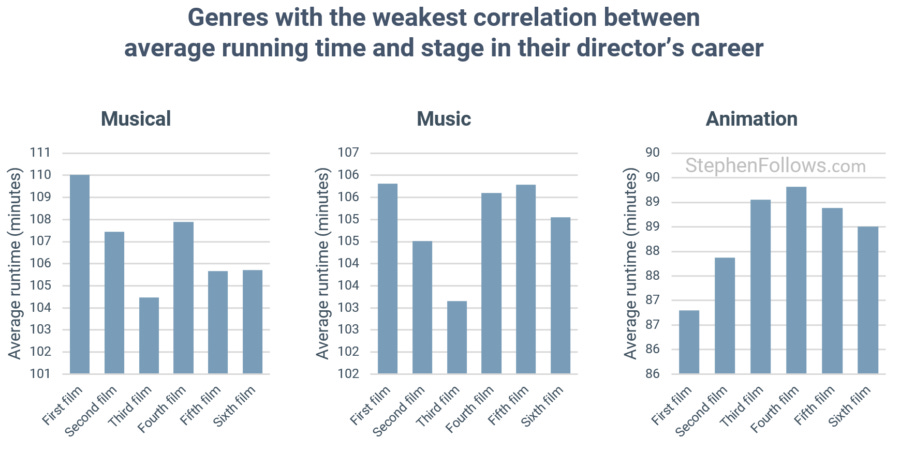

And here are the ones with the weakest connection. Interestingly, musicals are the only genre of movie where more experienced directors don't tend to make longer films. Musicals are also the genre that typically has the longest durations across the board, so maybe they've already maxed out on their first movie.

(Note that the y axis values on the three charts above are not the same).

Why is this happening?

The data can reveal the trend but not the reasons behind it. My early thoughts include:

More power - As directors get more experienced, they get more power to push back against producers and other forces coming from the indie film market.

Bigger ambitions - As directors get more familiar with the process of making movies, they are able to create and tell bigger stories and go deeper into ideas and themes.

More support - First-time films are invariably smaller in budget and have fewer industry supporters to help them. These limitations can restrict a director's ability to tell the full version of their vision.

These are just my first thoughts as to why more experienced directors tend to make longer movies. But what do you think? Add your thoughts, theories and experiences in the comments below.

Further reading

If you enjoyed today's piece then you may enjoy reading some of my past articles on related topics:

Does one page of a film script really equal one minute of screentime?

Are rom-coms shorter (and worse) than serious romance films?

Notes

The data for today’s research came from a variety of sources, including IMDb, Wikipedia and Movie Insider. This research is focused on fiction feature films (so not short films, TV movies, documentaries, etc) and includes all movies produced, not just those that were released in cinemas. I excluded any films with a run time under 60 minutes, over five hours or without a publicly available runtime.

I allowed each movie to have up to three genres, which was derived as an aggregate of all the sources listing that movie. Across the dataset, the average movie had 1.7 genre classifications.

The research was centered around directing credits, not around movies. This means if there was a film with two directors, the data would treat them as two data points rather than trying calculated an average for the movie. Only around 6% of movies have more than one director (more on that here).