What's happened to UK low-budget film production?

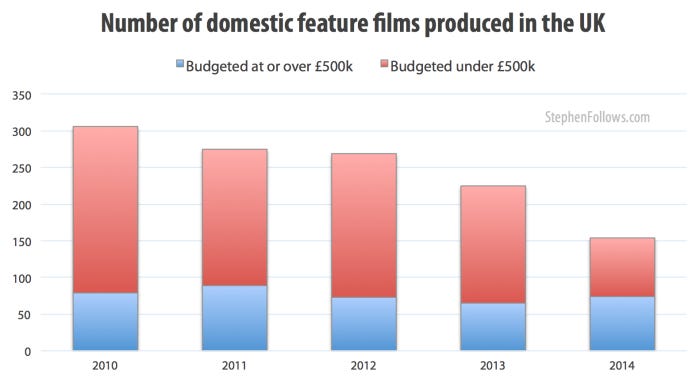

Today's article is looking at the recent decline in the number of films being made in the UK, specifically the dramatic fall in low-budget film productions. Every year the BFI publishes a Statistical Yearbook, which is a collection of facts and figures about the UK film industry. For the fourth consecutive year, they have recorded a fall in UK film production and the number of films being made on under £500,000 has fallen by 50% between 2010 and 2014.

In order to work out what's going on with low-budget film, we need to define what types of films are made in the UK...

Inward Investment - Films which are substantially financed and controlled from outside the UK. They shoot in the UK because of ...

Script requirements (eg locations); and/or

The UK’s filmmaking infrastructure; and/or

To access money via the UK film tax relief.

Co-productions - Films made across two or more countries whereby the film has multiple nationalities (i.e. the film is officially both a British film and a French film).

Domestic - These are films produced by a UK production company and made wholly or partly in the UK. This is the type of film which has experienced a sharp decline in production in the past few years.

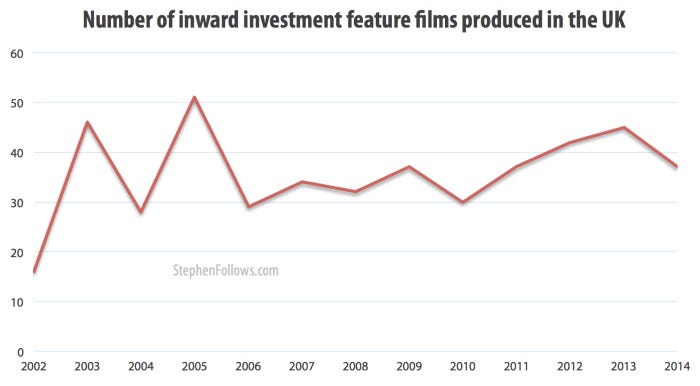

Inward investment

Thanks in part to the popular UK Film Tax Credit and to the quality of UK crew and facilities, the UK has seen a steady growth in inward investment films. The majority of these are American films from Hollywood studios, although in the past there have been a number of projects from India. In 2014, 17 out of the 37 'inward investment' films had budgets of over £30 million.

In 2014, inward investment only accounted for 17% of the films shot in the UK, up from 14% in 2013. However, more than four out of every five pounds spent on film production in the UK comes via inward investment (81% of total spend in 2013 and 84% in 2014).

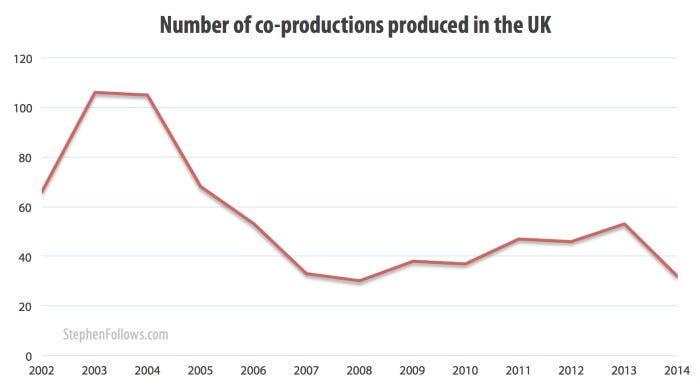

Co-productions

Co-productions are a method by which filmmakers can have their film officially classed as having multiple nationalities in order to access funding and tax benefits from more than one country. Co-productions are only possible if the two countries involved have a bilateral treaty (the UK currently has treaties with Australia, Canada, China, France, India, Israel, Jamaica, Morocco, New Zealand, the Occupied Palestinian Territories, South Africa and is soon to be signing one with Brazil) or if both countries are signed up to the European Convention on Cinematographic Co-production.

Co-productions have declined sharply in the UK since a change in the law which limited the amount co-productions can claim back via the UK Tax Credit to a percentage of the UK spend, not the whole budget. In 2014, co-productions accounted for 14% of films made in the UK.

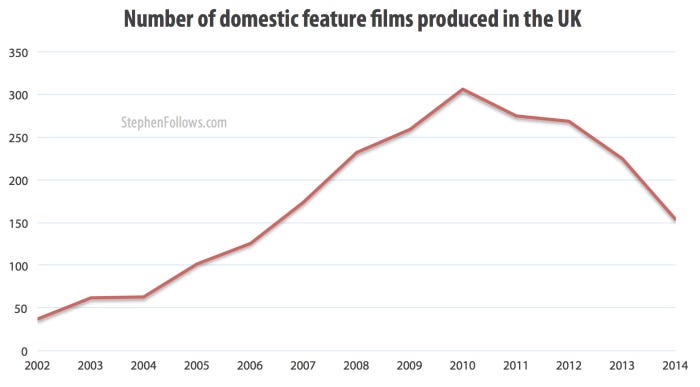

Domestic films

All films shot in the UK contribute to the UK film economy but when most people use the term "the British film industry" they normally are referring to domestic UK films. These are films made by UK productions companies, largely financed by private individuals and without support from Hollywood studios.

Between 1994 and 2010, UK domestic production increased ninefold, from 33 films in 1994 to a staggering 306 films in 2010. This was in part due to a dramatic fall in the cost of making a feature film and to the increase in the level of government funding available, via the UK tax credit and its predecessors. (Another factor is the support given by Lottery-funded bodies such as the UK Film Council, the BFI and regional screen agencies but it's hard to be able to pinpoint what impact they have had on production levels).

The decline of the past four years

Between 2011 and 2014, the number of domestic UK films has fallen by half, from 306 in 2010 to 154 in 2014. Almost all of this decline has been limited to films budgeted under £500,000.

What's happening to low-budget film production?

To be honest, I'm not sure. The decline could be down to a number of factors.

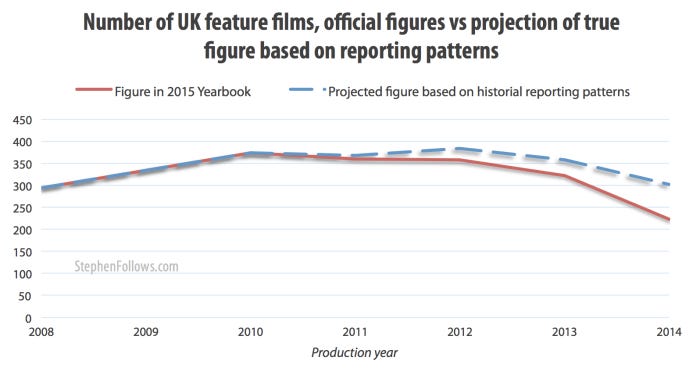

The first of which is underreporting. Today's figures come from the BFI who do a marvelous job tracking UK film productions and each year they publish a review of the previous year's figures via their Statistical Yearbooks (i.e. the 2015 Yearbook contains the figures for films shot in the UK during 2014). There is no legal requirement for filmmakers to inform the BFI of their production and so the BFI has to use a number of sources to generate these numbers. In many cases, the first the BFI hear of a film is when the production company applies for tax relief via the Cultural Test, which can only happen after the film is complete.

This means that with each new edition of the annual Yearbook, the BFI revise their figures from previous years. For example, the 2011 Statistical Yearbook listed 275 films as having been shot in the UK in during 2010 but by the time the 2015 Statistical Yearbook had been published, the 2010 production figure had risen to 373 films. I took a look at the changes in production data for the past five years and found...

Across all films shot in the UK, the figure for the previous year's production levels (i.e. the 2010 data in the 2011 Yearbook) only includes 74% of the films which will eventually be attributed to that year (i.e. the 2010 data in the 2015 Yearbook).

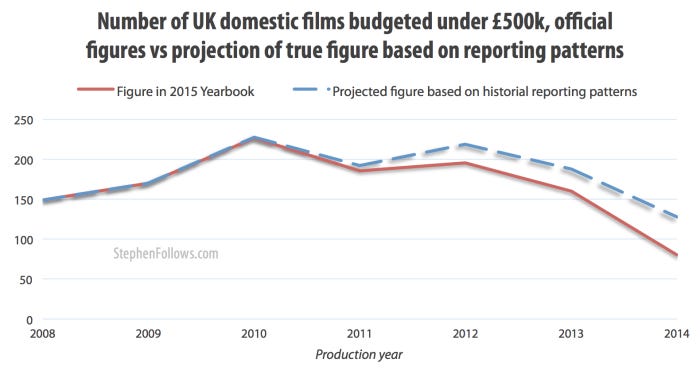

For domestic films budgeted over £500,000 93% are listed in the following year.

For domestic films budgeted under £500,000, the films listed in a new Yearbook for the previous year account for only 64% of the films which will eventually be tracked.

So, if the current pattern continues then we should expect the official count of the number of films made in the UK in recent years to be revised upwards in coming Yearbooks. Using the historic patterns, I have projected how the production data for 2008-14 will look in the fullness of time.

And this underreporting is most acute in low-budget film, due to the challenges in finding these productions before they are distributed, screened at film festivals or apply for their tax rebate upon completion.

(This all leads to a philosophical question... If a micro-budget film shoots in the forest but there's no-one there to distribute it, is it really a film...?)

So even when we take into account underreporting, low budget film in the UK have experienced a sharp decline, from 307 in 2010 to 216 in 2014 (both projected figures, as detailed above). Other reasons could include...

A regression to a more 'normal' level after an unsustainable boom caused by the financial crisis. It has often been said that the film industry is recession proof as when consumers have less money to spend they reduce their consumption of expensive goods and rely more on cheaper entertainment, such as movies and television. Further more, the recent financial crisis saw a number of previously well paid individuals being forced to find new careers. (Anecdotally I have heard from a number of UK film training providers that demand for introductory film training increased after the financial crisis). So one could make a case that the recent boom in filmmaking was caused by a perfect storm of new tax rules, the proliferation of high-end digital filmmaking equipment and increased funding from high net worth individuals who were looking to start a career in filmmaking.

It's a generational thing. Making a feature film used to be much more of an achievement than it is today. The generation of filmmakers who learnt on celluloid film (I count myself among this group) have regarded the recent shift to professional digital filmmaking as a chance to finally achieve the previously-unachievable goal of making a feature film. They ran out in their hundreds and shot everything that moved. However, the next generation of filmmakers grew up in the digital revolution and so making a feature film is less of an achievement. The turnover in filmmakers is quite high, as I've shown before, with only one out of five feature filmmakers making a second film. This means the people producing feature films in 2010 are a very different group of people to those producing features in 2014.

The increase in aspirational alternatives to making a feature film. The route into filmmaking used to be fairly linear - small short films lead to larger, funded short films which hopefully lead to features. Feature films were the main goal as there were few aspirational alternatives. However currently many filmmakers are making content directly for the web (web series, vlogs, comedy sketch series, etc) or being drawn towards a career in television by the recent trend of high-end epic series (such as Game of Thrones, House of Cards, etc).

The glut of films caused an over-supply, meaning that more recent films have a harder time securing finance. In the past decade, the number of films available to film buyers has massively increased (727% times in the UK between 2002 and 2010) whereas the demand from consumers has not grown by an equivalent amount (over the same period UK cinema admissions shrank by 4%, from 176 million in 2002 to 169 million by 2010). This means more films are not able to secure distribution and therefore their investors are not repaid. The films shot during the boom in 2010 would have been approaching investors in 2008 and 2009, using recoupment data from films released in the previous ten years or so. This would have painted a much rosier picture of film investment than the figures filmmakers who shot in 2014 had to work with.

But these are just my theories. I am keen to hear what readers think about this recent decline. Feel free to leave a comment below or contact me directly.

Epilogue

It should be noted that a decline in the number of feature films being made is not necessarily a bad thing. Many industry professionals felt that the recent boom in filmmaking was harmful to the industry as it flooded an already crowded market and hurt the image of film as a viable investment. In addition, many of the films made on the smallest budgets involved people working for free and/or in unprofessional environments.

Personally I don't see an increase or decrease in UK film production as inherently good nor bad. I think it's important that our industry is inclusive and allows people from all backgrounds to get involved if they want. There's no doubt that too many films being made is harmful to the industry but I like to think that the industry is more accessible than in the 1990s where feature filmmaking was the preserve of the connected, the rich and the crazy.