A major new study into gender inequality in the UK film industry

As regular readers will know, for the last nine months I've been working on a deep and comprehensive study of gender inequality in the UK film industry.

Today I'm pleased to be able to share the results (although less pleased with the content of the results!).

You can download the full report here and I have summarised the key findings in this article.

The report is broken down into three main sections...

Studying the current situation. We studied every feature film shot in the UK between 2005 and 2014 inclusive, looking at the gender of directors as it related to genre, budget, audience reaction, critical reviews and box office performance. We also looked at the gender of other crew on those films, including writers, producers, 1st ADs and directors of photography. We looked at the gender of people and projects backed by all of the film public bodies in the UK, as well as gender among film students, TV directors and theatre directors.

Assessing why the gender inequality exists. Using the data from the previous section, and via interviews with over 100 industry professionals, we looked at the reasons why such a large gender inequality exists and fails to improve. We tracked the journey directors make from student to working professional, measuring gender employment at each stage and assessing the challenges faced by female directors. Finally, we brought together these findings to explain why the industry's gender inequality survives.

Suggestions for redressing the gender imbalance. Based on our understanding of what was happening and why, we suggested actions which the industry could take to redress the gender inequality.

The report is 140 pages long and so what follows below is a very short precis. Each statistic, finding and suggestion is expanded upon in the report, so if anything piques your interest I would suggest you jump to that section of the report. At the bottom of this article you'll find a long list of our findings. Before that, I want to take you on a journey through the process and outcomes of the report.

Women are poorly represented within directors of UK films

We studied a total 2,591 films released between 2005 and 2014, inclusive. In that ten-year period, just 13.6% of working film directors were women.

Perhaps more problematically, there has not been any meaningful improvement in the representation of female directors in our studied period. In 2005, 11.3% of UK films had a female director but by 2014 this had only increased to 11.9%.

Female directors are also disadvantaged in their career progression and the opportunities they receive even after directing their first film. On average, female directors will direct fewer films in their career and are less likely to receive a second, third or fourth directing gig. Furthermore, as budgets rise, fewer female directors are hired and those that are hired are disproportionately limited to certain genres.

Female representation is poor across most of the UK film industry

Data on the crews of the films we studied revealed that the disparity between men and women, although most pronounced for directors, is evident throughout the industry. Of the main key head of department roles, only two had greater than 50% female representation with the rest ranging between 6% and 31%. Similarly, only casting, make-up, and costume departments have a majority of female crew, meaning of the seventeen crew credits we studied, fourteen had fewer women than men.

However, the scale of the disparity between men and women in crews was not as stark as that between key creatives, which in turn was not as severe as that between male and female directors. The general trend is for the percentage of women in a given role to broadly be dependent on the seniority of that role. In other words, the more senior a role, the less chance it is held by a woman, and, by extension, the less chance a woman has of being hired for it.

Female representation in key creative roles and among film crews has also stagnated across the last decade. Across the whole of the industry there is no meaningful trend towards greater representation of women or any real improvement in their career prospects.

Public funding for female-led films dropped significantly

Over a fifth of UK films receive some form of public funding (development and/or production), and we found that those films had a higher representation of women amongst directors. However, the overall average hides a clear decline in the support of female directors. In 2007, 32.9% of films with UK-based public funding had a woman director, but by 2014 that had dropped to just 17.0%.

We also discovered that the majority of UK film public bodies do not adequately track the gender of applicants and awardees.

Film students and industry 'new entrants' have gender parity

UK film students, like the UK population as a whole, are broadly 50% male and 50% female. Similarly, entrants to the film industry are 49% female.

Yet as they begin to progress through their careers and gain the credibility required to launch a directing career the disparity begins to emerge. As we’ve seen, women are already underrepresented in the majority of film crew departments and the difference between male and female representation increases as we progress to key creative roles.

Female directors face similar issues in other important stages of their career development: just 27.2% of British short film directors and 14% of drama television directors are female.

Once they become directors they struggle to progress to larger budgets (16.1% female directors on low-budget films compared to 3.3% on high-budget films) and to make additional films (12.5% of directors who have made two films are female compared to just 4.0% on directors who have made four or more).

The report's findings paint the picture of an industry where female directors are limited in their ability to become directors and their career progression once they do. They are limited in the number of films they can direct as well as the budget and genre of the films they do. They are less likely to be hired at all stages of their careers and find it proportionately more difficult to be hired to senior roles and gain the credibility and experience needed to launch a successful directing career. And there is no meaningful sign of improvement without concerted action to resolve these issues.

The causes of gender inequality among UK film directors

We found no evidence that that fewer women wish to become directors than men. Given the lack of any disparity during film education or at the point of entering the career, the scale of the disparity at later stages in directors’ career progressions and its consistency through careers and across the industry, this explanation simply seems highly unlikely to be even close to a full explanation of the issue.

If the personal choices of women in the film industry is inadequate as an explanation of the disparity between male and female directors then, given individual decisions and contacts are the gate-keepers to progression and success within the industry, whatever the root causes of the inequality are, the point at which they are realised must involve some action of the individuals with power in the industry. In other words, the disparity must be a result of the preferences of those making hiring decisions rather than those applying for those positions.

We found evidence to support this hypothesis in the difference in representation of female employees under female directors and heads of department and their male counterparts. Female key creatives have a notably higher percentage of women in their departments and female directors hire a greater percentage of female key creatives. Hence, the differing preferences of male and female employers is clearly resulting in a difference in their hiring practices.

However, we found no evidence of any organised, conscious or deliberate efforts to exclude women from the industry or certain positions within it. Therefore, it is our belief that the gender imbalance is primarily due to an unconscious bias.

By studying three aspects of UK films, namely audience ratings (popularity), critics rating (quality), and box office (profitability) we were able to show that the evidence available is not adequate to justify any such preference. Meaning that there is no evidence to support the notion that the bias against female applicants is in any way justified.

Hence, the best initial explanation of our findings is that they are the result of a widespread, unjustified, and unconscious bias within the industry. However, this is far from a full explanation. It is important to note we have not seen evidence to support the suggestion that those making hiring decisions genuinely hold such biases in a wider context, and we do not believe this to be the case.

The lack of any trend towards an improvement in female representation, despite the frequent churn of individuals within the film industry, suggests that there are systemic issues which are sustaining and perhaps creating these biases. In simple terms, the individual instances of bias are not the problem themselves but rather a symptom of it.

We identified four principal systemic issues we believe produce, allow, and protect the disparity between men and women in the film industry:

First, there is no effective regulatory system to police or enforce gender equality. Without adequate protection and in an industry where hiring is conducted primarily privately and reputation is of great importance (discouraging any complaints by a discriminated upon party) unfair hiring practices go unreported and ignored. In addition, just 7% of UK films make a profit, thereby effectively removing the power of the market to deselect unsuccessful projects and methods. Without competition driving change and with no external pressure to force change there is no reason to deselect damaging ideas, so no change occurs.

Second, the pervasive nature of uncertainty, which creates a climate of insecurity, leads to illogical and ritualistic behaviours, which results in the industry operating based on preconceived notions of the archetypal director, rather than on their individual abilities and talents.

Third, the permanent short-termism in the film industry discourages long-term thinking and prevents positive HR practices, best exemplified by the un-family-friendly nature of the industry. The vast majority of producers work film to film and build the team and structure for each project anew and at considerable pace. This means hiring must often, by necessity, rely on traditional methods and preconceived notions, as there simply isn’t time to conduct a more extensive hiring process. In addition, the sporadic employment, long hours, and unpredictable and constantly changing nature of the work make it nearly impossible to effectively progress in the industry whilst also being the primary care-giver in a family, a role which is disproportionately held by women.

Finally, inequality in the film industry is symbiotic – the various instances of inequality across various areas of the industry reinforce and facilitate each other – creating a vicious cycle. First, male employers hire a greater percentage of men, resulting in a greater percentage of men in positions to hire others. And second, a lack of female directors leads to a lack of role models for those starting out and greater pessimism about their prospects, which may discourage many candidates. And third, low female representation leads to low regard for female directors which in turn leads to low female representation.

We believe the evidence suggests that these four systemic issues protect and sustain the outdated, unconscious bias of the individuals within the industry, and these in turn result in fewer women being hired and fewer films being directed by women.

Providing solutions to remedy the gender inequality

We suggest the current vicious circle which perpetuates the under-employment of female directors can be used as the engine of change, becoming a virtuous circle, as shown below.

To this end, we have outlined three solutions to these systemic issues, which we believe would greatly improve the representation of female directors and women in the industry more generally.

First, we propose a target of 50/50 gender parity within public funding by 2020. Only 21.7% of the projects we studied that were funded by UK based funding bodies were helped by a female director. A target that half of films backed by UK-based public bodies be directed by women by 2020 offers one of the most direct opportunities to redress the imbalance between male and female directors on publicly backed films. In addition, we suggest that all bodies which disperse public money within the UK to films or filmmakers are required to provide full details of the gender of applicants, grantees, and key creatives on each production. The current lack of any widespread, comprehensive data has limited awareness of the issue and so slowed efforts to change it.

Second, we propose amending the Film Tax Relief to require all UK films to account for diversity. The Film Tax Relief (FTR) is the largest single element of government support for the UK film industry. It touches all films, no matter their origin, scale, genre, creative contents, or market potential and therefore it is one of the most powerful mechanisms with which to effect industry-wide change. We propose an additional ‘diversity’ dimension to the requirements all films must fulfil in order to be eligible for Film Tax Relief, within which gender would be specified group

Finally, we propose an industry wide campaign to rebalance gender inequality within UK film, whereby different parts of the film industry take responsibility for the respective roles they have to play in tackling gender inequality and enabling more women to become directors and direct films. Public bodies and agencies should continue to lead a coordinated campaign raising awareness and promoting action and intervention, including: funding, career support, unconscious bias training and challenging industry myths. The report includes suggestions and methods for running this campaign.

In combination, we believe these solutions would go much of the way towards fixing the gender disparity in the film industry. Not only by directly improving the opportunities for female directors and the number of female directed films, but also by removing the systemic issues which propagate inequality in the industry.

Why action is needed

What is clear is that without serious, concerted effort to alter the hiring practices in the industry, this is not an issue that will resolve itself. However, the reasons to implement such change are numerous and extend far beyond simply the benefit to women within film itself.

By expanding and diversifying the pool of working directors we increase the range and variety of the films we make and the stories we tell. By shutting out entire segments of society we exclude unique voices and limit the scope of our culture as a whole.

Equally audiences are limited in the films they can see. A male-dominated film industry leads to male-focused films, leaving women not only underrepresented amongst directors but underrepresented in the art and stories themselves.

The film industry benefits hugely by improving the meritocracy of its hiring decisions. By hiring more women in prominent positions we improve the opportunities for other talented women within the industry and create role models to inspire the next generation, further increasing the talent to choose from.

Finally, and most simply, it matters because it is unfair and unjust for any individual’s opportunities to be limited simply because of their gender and because this sort of discrimination is outdated, illegal and immoral.

Film occupies a unique position, sitting at the crossroads between being product and art. It has great influence over what we as a society believe and how we feel about it. It not only responds to but shapes public opinion, and so it has a greater obligation to represent our society as a whole and to project informed, developed beliefs than perhaps any other industry. The disparity between male and female directors and the inequality in the industry more generally means we are failing in this obligation. But it is well within the industry’s power to change this.

Long list of key statistics and findings

Click the chapter titles to read a summary of the key findings within each chapter.

Section A: The Current Landscape for Female directors

[toggle title_open="Chapter 3: Female directors within the UK Film Industry" title_closed="Chapter 3: Female directors within the UK Film Industry" hide="yes" border="yes" style="default" excerpt_length="0" read_more_text="Read More" read_less_text="Read Less" include_excerpt_html="no"]

The percentage of UK directors who are women

Just 13.6% of working film directors over the last decade were women.

Only 14.0% of UK films had at least one female director.

UK films are over six times more likely to be directed by a man than a woman.

The issue over time

In 2005, 11.3% of UK films had a woman director; by 2014 this had only increased to 11.9%.

Career progression for female film directors

During their careers, female directors tend to direct fewer films than male directors.

Men are 13.1% more likely to make a second film than women.

Female directors make fewer second, third and fourth films than men.

The budget level of female-directed UK films

As budgets rise, fewer female directors are hired.

16.1% of films budgeted under £500,000 have a woman director.

That figures drops to just 3.3% of films budgeted over £30 million.

The genre of female-directed UK films

Female directors appear to be limited to genres traditionally viewed as “female”.

Female directors are best represented within documentaries, drama, and romance films, while having the lowest representation within sci-fi, action, and crime.

Although female cinema-goers prefer some genres more than others (i.e. drama over sci-fi), the extent of this preference is not as stark as the employment of women as directors in each genre.

The quality of female-directed films

Films by female directors get higher ratings from film audiences and film critics compared to films by men.

22% of ‘Top Film Critics’ on Rotten Tomatoes are women.

36% of reviews written by female film critics and 21% of reviews written by male critics were about films directed by and / or written by a woman writer

[/toggle]

[toggle title_open="Chapter 4: Female representation in the UK film industry" title_closed="Chapter 4: Female representation in the UK film industry" hide="yes" border="yes" style="default" excerpt_length="0" read_more_text="Read More" read_less_text="Read Less" include_excerpt_html="no"]

Women in key creative roles on UK feature films

Only two out of the nine key creative roles have above 50% female representation.

25.7% of producers of UK films are women.

Women account for 14.6% of screenwriters on UK films.

Female crew members on UK feature films

The transportation, sound, and camera departments have under 10% women crew members.

Only casting, make-up, and costume departments have a majority of women crew.

Female representation among department heads and their crew

In the vast majority of cases, the more senior a role is, the lower the percentage of women holding the role is.

A crew member working in production is almost twice as likely to be women (49.9%) than the producer (25.7%).

The data suggests that in the vast majority of departments within UK film, women have a harder time working their way up the chain than men.

The weight of evidence suggests that there is a pervasive belief within the film industry that women, outside of the roles and departments that have been traditionally viewed as “female”, are less able to hold senior roles than their male counterparts.

The effect of a woman director on overall female representation

30.9% of crew working on female-directed films are women, compared with 24.1% of crew on male-directed films.

The difference is starkest for writers, where 65.4% of writers on female-directed projects are women compared with just 7.4% on male-directed films.

Changes in female representation on UK feature films over time

There is no meaningful trend towards improvement in female representation across the UK film industry.

[/toggle]

[toggle title_open="Chapter 5: Female directors in publicly-funded films" title_closed="Chapter 5: Female directors in publicly-funded films" hide="yes" border="yes" style="default" excerpt_length="0" read_more_text="Read More" read_less_text="Read Less" include_excerpt_html="no"]

Female directors within UK publicly-funded feature films

25% of UK films 2005-14 received some form of public funding.

21.7% of the films with UK-based public funding had a woman director.

Public funding support for films with female directors has fallen dramatically in the seven years.

In 2008, 32.9% of films with UK-based public funding had a woman director whereas in 2014 it was just 17.0%.

Female directors within UK Regional Film Funding Schemes

37.3% of funding awards via Northern Ireland Screen (April 2007 to March 2015) went to female applicants.

49.7% of funding awards via Creative England (Jan 2011 to October 2015) went to female applicants.

Women applying to Creative England have a much higher success rate (16.6%) than men applying (10.1%).

29% of funding awards via Ffilm Cymru Wales (Jan 2014 to May 2015) went to female applicants

The BFI, Creative Scotland and Film London could not provide gender statistics for their funding applications.

[/toggle]

[toggle title_open="Chapter 6: Female directors in related sectors" title_closed="Chapter 6:Female directors in related sectors" hide="yes" border="yes" style="default" excerpt_length="0" read_more_text="Read More" read_less_text="Read Less" include_excerpt_html="no"]

Female directors of British short films

Women make up 27.2% of directors of the 4,388 short films in the British Council’s British Film Database.

Female directors of films shortlisted at major international film festivals

Within our sample of major international film festivals, female directors are better represented within short films (25.4% of directors) than within feature films (15.9%).

Sundance had the highest female representation within feature films (32.6% of directors) and Cannes had the lowest (8.5%).

Film festival juries with male majority are more likely to give awards to male directors.

Female directors within the UK television industry

There is compelling evidence for the existence of gender stereotyping of television programmes directed by women across genres, particularly in factual television.

Only 14% of drama television programmes are directed by women.

Production executives responsible for hiring were (in 2013) unaware of low figures for female directors.

Women within the UK theatre industry

Women are underrepresented in senior positions in the UK theatre industry.

The larger the organisation, the harder it is for women to progress to senior roles.

There is an issue with career progression for women as artistic directors in UK theatre.

It’s not the result of a lack of supply of women candidates.

Female directors in European film

Between 2003 and 2012, 16.3% of European films had a woman director.

The majority of top female-directed films had female protagonists, were told from a women’s point of view and dealt mostly with romance and relationships.

Very few films by male-directors had these elements.

Women within UK film degree courses

Women account for roughly half of all film students.

The percentage of women applying for film-related degree courses is increasing.

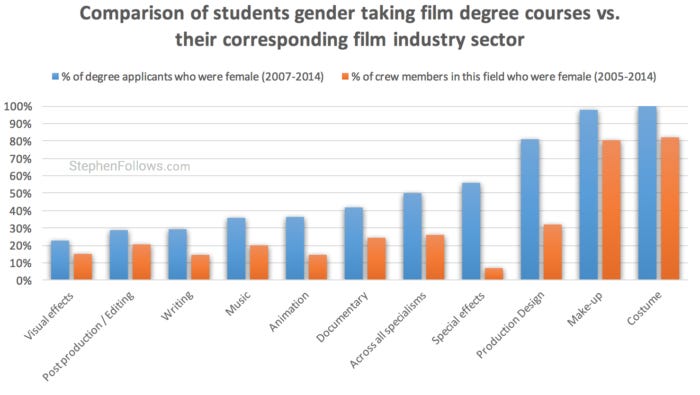

For each specialism, women are better represented in UK film degree courses than within crew employment in the UK film industry.

On average across all film-related degree programmes (2007-14) each course received 337 applications for sixty-six student places, meaning that one in five applications were successful.

[/toggle]

Section B: Why Are So Few Female Directors Hired?

[toggle title_open="Chapter 7: Routes into Directing" title_closed="Chapter 7: Routes into Directing" hide="yes" border="yes" style="default" excerpt_length="0" read_more_text="Read More" read_less_text="Read Less" include_excerpt_html="no"]

The path to becoming a professional film director in the UK

When we asked a number of working UK film directors about their route into directing, the most common responses were that they studied a film-related course, worked in television, made short films, and/or worked in other crew roles.

Education

Four out of five working film directors have a degree, although only 23.1% of directors have a film degree.

Entering the film or television industry

49.4% of Runners and Production Assistants in the UK Film Industry are women.

The principal method of advertising an entry-level job in the UK film industry is Facebook.

In employability terms for new entrants, owning a film degree is significantly less important than owning a driving license.

Gaining credibility

All of the six most common proving grounds for future-directors have an underrepresentation of women.

The crew roles which are the most useful to a director’s early carer are all male-dominated, including editing (14.4% women), producing (25.7%) and the camera department (9.8%).

The first directing gig

First films are typically on the lower budget range.

Most public funding schemes aimed at early filmmakers require the director to have a portfolio of work.

Success with a debut feature film can be measured in the film’s quality, box office performance and in the intangible ‘industry reputation’.

Career development

Making a second feature film is often harder than the first.

The most commonly cited reasons why a director failed to make a second film are not gender specific.

And yet, fewer female directors make a second film than their male counterparts.

Many of the directors who do have opportunities to make subsequent films feel severely limited in the types of films the industry will support them to make.

[/toggle]

[toggle title_open="Chapter 8: Why the gender disparity exists" title_closed="Chapter 8: Why the gender disparity exists" hide="yes" border="yes" style="default" excerpt_length="0" read_more_text="Read More" read_less_text="Read Less" include_excerpt_html="no"]

Individual Bias

We have found no evidence that gender inequality is the result of any conscious or deliberate effort to keep women out of the film industry.

There is no indication that the kinds of people attracted to work in film are disproportionally misogynistic or anti-women compared with the general population.

It is our belief that the gender imbalance is due in large part to unconscious bias, rather than considered actions by industry insiders.

We believe that this bias is created and sustained by a number systemic issues within the UK film industry.

Systemic Issues

Meritocracy tends to depend on either strictly enforced regulation or balancing market principals. Neither is clearly apparent in the UK Film Industry.

Only 7% of theatrically distributed British films return a profit, which undermines the ability of market forces to be the engine which drives change away from anti-commercial over-reliance on male directors.

The lack of certainty in the film business creates two major undesirable outcomes: firstly, a fear of doing something different resulting in the veneration of rituals and conventions over facts or reason. And secondly, a reliance on ‘on the job’ training resulting in a lack of progress based on new ideas and methods.

These, in combination with the pressured environment decisions are made under, have led to and maintained a reliance in the film industry on preconceived notions of the archetypal director, rather than on actual evidence of ability.

An issue further protected by permanent short-termism in the industry.

Film audiences do not care about the gender of the director, meaning that hiring a woman director is not negative from a film sales perspective.

Films that women chose to watch tend to have an above-average proportion of women writers, producers and directors, suggesting that if producers wish to target women cinema-goers then hiring a woman director can be advantageous.

There currently exists a vicious circle, whereby the lack of female directors leads to the image of a typical director being that of a man, which creates the unconscious assumption that men are better at directing, which leads to fewer female directors.

[/toggle]

Section C: Fixing the Gender Inequality issue

[toggle title_open="Chapter 9: Moving forward" title_closed="Chapter 9: Moving forward" hide="yes" border="yes" style="default" excerpt_length="0" read_more_text="Read More" read_less_text="Read Less" include_excerpt_html="no"]

The underrepresentation of female directors in the UK film industry has a number of negative externalities; for the industry, for film audiences, and, above all, for overlooked female directors.

The underemployment of women in the UK film industry has been reported on for decades.

The film industry shows no signs of self-correcting the current gender imbalance.

Film industry professionals do not believe they are consciously using gender as a factor when assessing directors.

Our suggested solutions target the two main causes of the gender imbalance; unconscious individual bias and the systemic issues which allow this to continue.

The current vicious circle which perpetuates the under-employment of female directors can be used as the engine of change, becoming a virtuous circle.

We propose:

A target of 50/50 gender parity within public funding by 2020.

Amend the Film Tax Relief to require all UK films to take account of diversity.

A co-ordinated, data-lead campaign for gender equality across the UK film industry.

We also believe that it is worth investigating amending the UK Film Tax Credit to reward female-directed productions, although this suggestion requires further study.

We do not feel that naming and shaming producers or production companies who hire few / no female directors will be an effective route to improving the situation, and could even harm the cause.

We advise against campaigning on the suggestion that female directors are, by definition, better than male directors.

While the campaign for gender equity among film directors should be promoted loudly and widely, there is a real danger in championing minor (or invented) successes as it could lead to the perception that the situation is ‘in hand’, despite the lack of actual change.

[/toggle]

Notes

The report was only possible thanks to Directors UK, who provided support, resources and advice throughout the process. It also would not have been possible without the help and support of a large number of people. Not least, my co-author Alexis Kreager as well as Eleanor Gomes, Alyssa Thorne, Sophie Lifschutz, Edward Dark and the hundreds of industry professionals we spoke to for research. Thank you all.

If you're interested in reporting more on the topic then you may enjoy the following previous articles from myblog...