A bigger market is emerging for independent films worldwide

Audience habits, localisation workflows, and global rights deals are moving in the same direction, and the combined effect is larger than most people are treating it.

A larger market for independent films worldwide is emerging, and I don’t think the industry has fully taken on board the consequences yet.

To be clear, I think the individual forces behind this are widely known. But it occurs to me that the knock-on effects of these changes (a) have not yet played the huge role I suspect they might and (b) I don’t hear film professionals building this new reality into their plans.

This feels like a classic case of Amara’s Law, which states:

We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.

Many of the tools and behaviours I’m going to talk about today have been visible for a while, but taken together, and given time to settle, they may reshape the market more profoundly than most people currently expect.

I’ve grouped the changes into three broad ‘forces’:

Audience behaviour has shifted, with viewers in English-speaking markets now routinely watching subtitled and non-native content.

Localisation is becoming faster and cheaper, turning subtitles and dubbing from specialist bottlenecks into repeatable workflows.

Distribution operates globally by default, with availability and discovery increasingly crossing borders simultaneously.

Each, in its own sphere, is seriously reducing, maybe even eliminating, a major barrier to films.

Let’s set the scene…

Film in the early 20th century was a local affair

For most of the modern film industry, language set the practical limits of a film’s market.

A film made most of its money at home, as international distribution was hard to arrange and required physical distribution and localisation.

Some markets would have sympathetic neighbouring territories, thanks to shared languages and/or compatible cultures. But to access non-local income streams, you had to:

Connect with film professionals worldwide. The industry developed a model of three major film markets a year, in which filmmakers would have a single representative (a “Sales Agent”) who would negotiate with companies around the world (“Distributors”) to agree a deal for each country.

Once the deal was done, the film would need to be delivered to the distributor in each country, who would then adapt it for their territory. This usually meant getting it trimmed to meet censorship rules, translating the dialogue and on-screen text, and then either adding subtitles or re-recording all the dialogue with voice actors in the local language.

Finally, the film had to be marketed to consumers. Some films played up the foreign aspect of the title (in the US, Parasite was framed as a prestige title from a foreign country), while others tried to hide that it was a dubbed or subtitled title until the audience was in the cinema (in the UK Amélie was presented as a mainstream feel-good movie, rather than a subtitled French film).

In the second half of the 20th century, big films went global

As the commercial value of international distribution became clearer, the largest studios began to build global appeal directly into their films.

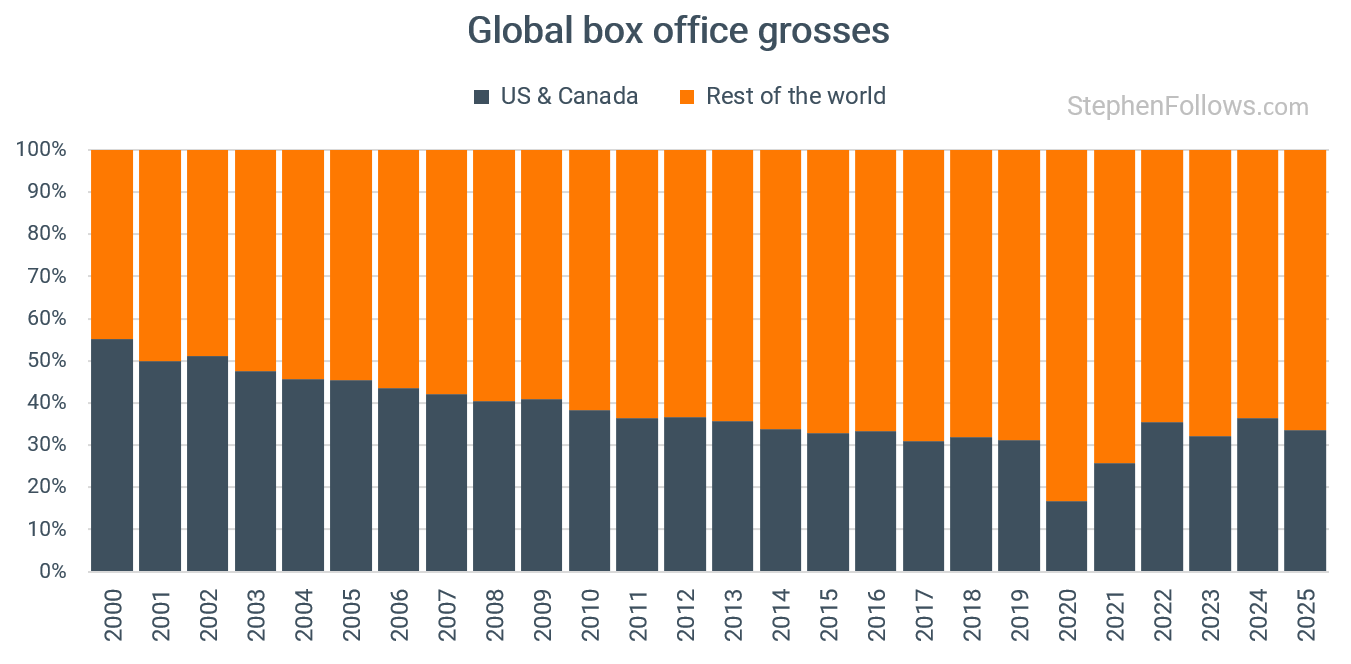

By the 1970s and 1980s, Hollywood was no longer treating foreign markets as a bonus on top of domestic success. International box office began to account for a growing share of revenues, particularly in Europe and Japan, and later in emerging markets across Asia and Latin America. By the late 1990s, it was increasingly common for US studio films to make more money outside North America than within it.

This shift shaped both financing and creative decisions. Films were selected, packaged, and developed with international travel in mind. Action, spectacle, and visual storytelling became more prominent, as they crossed language and cultural boundaries more easily than dialogue-heavy or culturally specific drama.

At the same time, audiences in many non-English-speaking territories became accustomed to consuming foreign films with subtitles or dubbing. Imported Hollywood titles dominated local box offices, and the infrastructure for localisation became well established. In these markets, watching films that were not in your native language became normal rather than exceptional.

English-speaking markets did not experience the same shift. Subtitles remained associated with arthouse cinema, foreignness, or effort. Dubbed content was often treated with suspicion or outright rejection.

As a result, non-English-language films struggled to break through in the US, the UK, and other English-speaking territories, even when they performed strongly elsewhere.

As studios leaned further into global revenues, stories were increasingly designed with worldwide potential in mind. Settings became more abstract or interchangeable, and films avoided political or historical elements that could be troublesome in key territories.

When China began to emerge as a major source of income in the 2010s, Hollywood was quick to change its movies. Red Dawn (2012) changed the invading army from Chinese to North Korean in post-production, and World War Z (2013) removed references that pointed to China as the outbreak’s origin.

My favourite example is Transformers: Age of Extinction (2014). When an intergalactic evil bounty-hunting robot attacks Hong Kong from outer space (aided by an army of killer drones), the film pauses mid-battle to show Chinese officials stating that the situation must be escalated to the central government because they can help, followed by shots implying swift, coordinated state-level intervention.

By the end of the 20th century, you could describe the global market for movies as:

The studios learned how to make films that travelled, but that came at the cost of narrowing the range of stories considered commercially viable at scale. Each new territory they released needed to generate significant revenue to justify the cost of adaptation and distribution.

Audiences in smaller, non-English-speaking territories grew accustomed to foreign imports with dialogue dubbing and/or subtitles, but the costs and hassle of localisation created a heavy friction point to true global expansion for indie films.

Most English-language territories never quite got on board with dubbing or subtitles, thereby limiting the appeal of foreign titles. A few would break out each year, but the marketplace accounted for only a fraction of English-language titles.

The 21st century is global, but movies are still catching up

By the early 21st century, most consumer behaviour had already gone global. We shop internationally, chat across borders, and consume news, culture, and commentary from anywhere with a connection.

But despite digital delivery, global platforms, and worldwide conversation, language remained a hard boundary for movies.

Non-English films were still framed as foreign, niche, or specialist in English-speaking markets. International availability does exist, but discovery, localisation, and audience behaviour haven’t yet aligned in a way that allows films to travel smoothly.

Over the last few years, three forces have been developing simultaneously, and together they have the potential to remove language as a meaningful barrier to audience reach:

First, audience behaviour in English-speaking markets has shifted. Watching subtitled and non-native content has become a routine part of viewing, particularly among younger audiences, and no longer sits at the margins of taste.

Second, the friction around localisation is falling. Subtitling and dubbing are faster to produce, easier to manage across multiple versions, and cheaper than they were even a few years ago. Tools that support this are now reliable enough to be used at scale.

Third, distribution now operates on a global footing by default. Platforms release content across borders, and discovery increasingly travels through shared recommendations, communities, and online conversation rather than national schedules.

Each of these changes is reshaping the market for movies, but taken together, they may completely reframe who the market is for.

Let’s look at them each in turn.

Force 1 - Audiences have changed what (and how) they watch

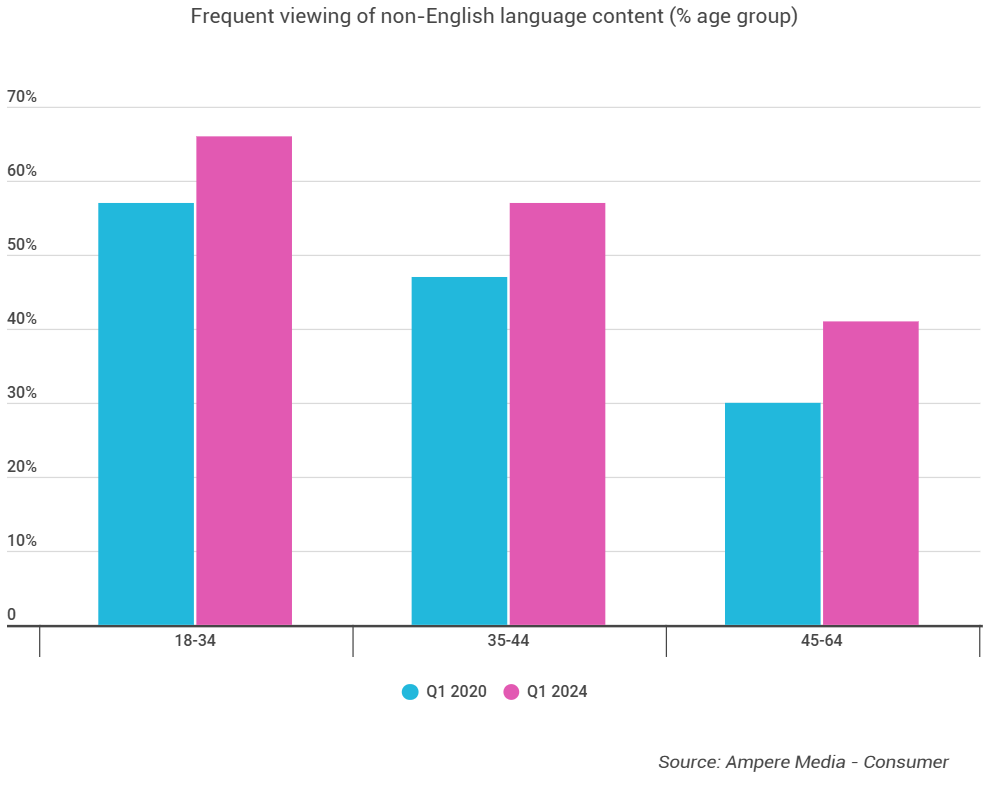

Non-English film and TV viewing has become fairly commonplace in English-speaking markets. Ampere’s tracking across the US, UK, Canada and Australia shows 54% of internet users aged 18–64 now watch non-English content “very often” or “sometimes”, up from 43% in Q1 2020.

The shift is strongest among younger viewers, and the older end is moving too. Ampere reports 66% of 18–34s regularly watch non-English titles, compared with 41% of 45–64s, with the older group rising from 30% to 41% over the same period.

The streamers are well aware of this and have built it into the core of their business models. Netflix says more than one-third of viewing in the first half of 2025 came from non-English language titles, and 10 of the 25 most-watched series in that period were non-English.

Subtitles have also become a default viewing mode. Almost half of all viewing hours in the US on Netflix happen with subtitles or captions turned on, and a 2022 Preply survey found that 50% of Americans watch with subtitles “most of the time”.