Can media coverage predict who wins an Oscar?

I analysed fifteen years of Oscar nominees to see whether the most-mentioned contenders in the trades tend to go on to win.

Over the past few weeks, Matthew Belloni and I have been talking about how the Oscar race functions and, in particular, the role of press coverage during the long stretch between September and February.

Matthew asked me to look into the connection between the volume of coverage nominees receive and who ultimately wins the Oscar.

To explore it, I gathered all acting and directing nominees from 2010 to 2024 and mapped how often each was mentioned in the main film trades during the six-month voting window. (See the Notes section at the end of this article for full details).

By comparing the nominee’s share of coverage with eventual outcomes, we can gauge how much coverage actually matters.

Let’s look at actors first, before turning to directors.

Does the trade press cover nominees more often?

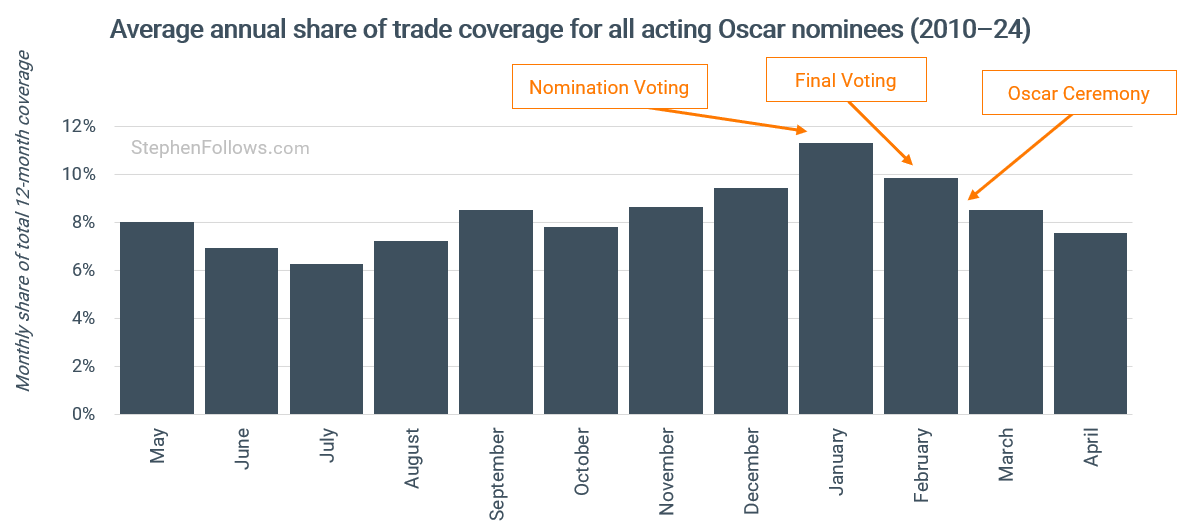

When we look at the monthly stats on the amount of coverage each nominee gets, we can see a strong up-tick as the ceremony gets closer.

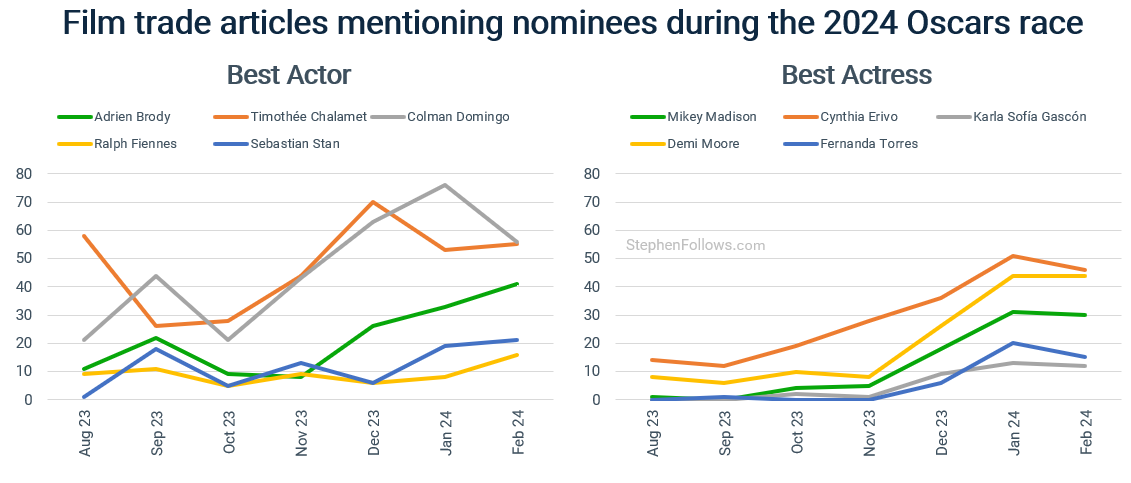

For example, in last year’s race, the best month for all five Best Actress nominees was January 2024. For the Best Actors hopefuls, three had their greatest amount of coverage in February, one in January and one in the preceding December.

This is a pattern which repeats each year, and makes sense when you consider the timing of the Oscar race.

Early possible contenders might be spoken about during the summer, but it’s from around September that “the buzz” starts in earnest. Publicists work in overdrive to secure favourable press coverage for their clients during the fall, in order to influence the voting for nominations in the new year.

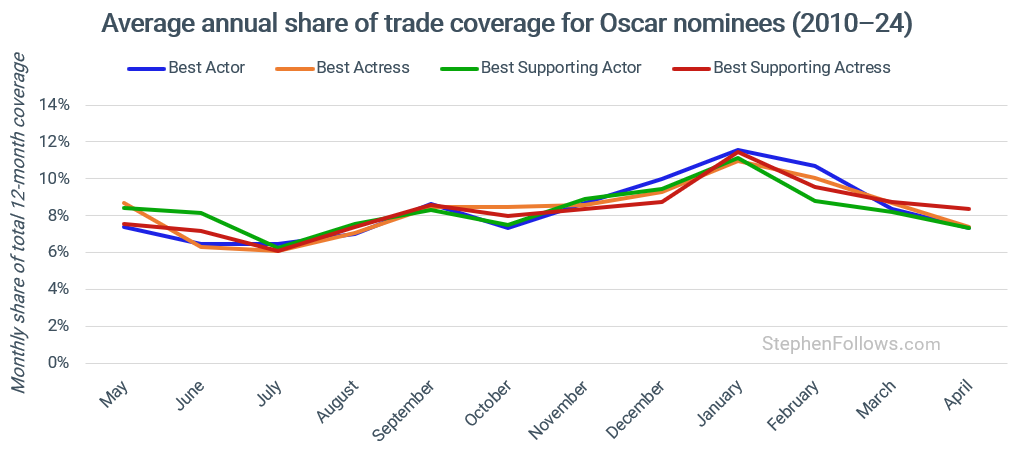

This is the same for all four of the major acting awards.

So we can say that being nominated for an Oscar means the film trade press will write about you more often as the event gets closer - no surprises there. But is there a useful link between the coverage and outcome?

There are two ways to think about what we’re asking:

The first is to ask “How often is the most talked about nominee the eventual winner?”. This gives us a quick answer to whether we can use this method as a predictor of Oscar glory.

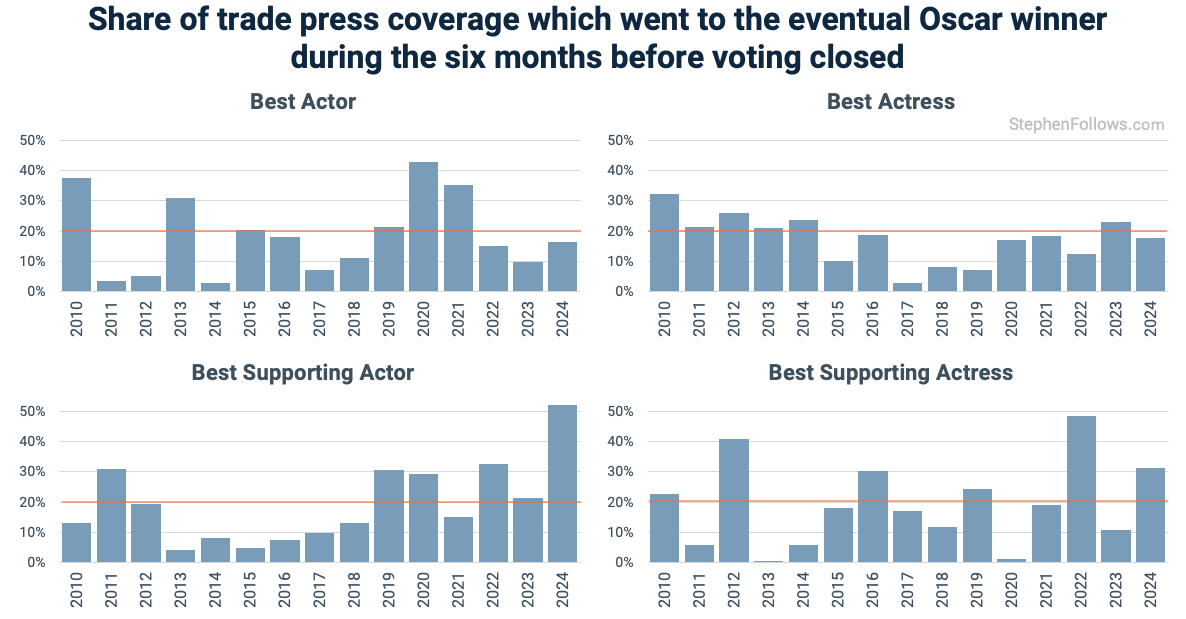

The second is to ask “Does the eventual winner get a disproportionate amount of coverage in the lead-up to the awards?”. In a five-person field, you would expect each nominee to receive 20% of all mentions if attention were shared evenly and/or random.

Q1. How often is the most talked about nominee the eventual winner?

Almost never. It’s extremely rare for the most talked about person to be the winner.

Over the fifteen years I studied, across all four acting categories, it happen just 8.3% of the time.

Best Actor: 0 out of 15.

Best Actress: 1 out of 15. Natalie Portman (2010).

Supporting Actor: 2 out of 15. Ke Huy Quan (2022) and Kieran Culkin (2024)

Supporting Actress: 2 out of 15. Anne Hathaway (2012) and Jamie Lee Curtis (2022).

So we can’t use this to predict winners. Damn - there go my dreams of making a fortune on the betting markets in a few months from now.

But can we infer some kind of soft signal to narrow the odds?

Q2. Does the eventual winner get a disproportionate amount of coverage in the lead-up to the awards?

Also no.

Across all acting nominations, the winners accounted for just 18.6% of the coverage - slightly less than they would have got if it were random.

What about directors?

The data for Best Director is even weaker. The winner director gets an average of 15.3% of the mentions - way under the 20% we would expect is things were random.

Only twice did the buzziest director go on to win the award - Alejandro G. Iñárritu in 2015 and Sean Baker in 2024. In every other year, the nominee who dominated the coverage was someone else entirely.

So who DOES get the most coverage leading up to the Oscars?

At the risk of sounding obvious, the most coverage is given to the most famous people.

Whenever the field of nominees includes someone who is already famous within the industry (think Nolan, Spielberg, Scorsese, etc) then they will receive the greatest amount of coverage.

Put simply, the effect of being an Oscar nominee is not enough to combat the normal power dynamics of the industry.

Does this mean it’s a waste of time doing press before the Oscars?

This question is a little above my paygrade. We can certainly say that there is no strong evidence from this dataset that nominees should seek every chance they can get at press coverage, purely in attempt to increase their chances of winning.

But there are more factors at play than we are tracking here, so who knows.

Matthew Belloni is a man who might and he said:

Back when I was running The Hollywood Reporter, it never ceased to amaze how downright available the stars and filmmakers became this time of year. Actors like Leo DiCaprio or Ben Affleck or Jennifer Lawrence, whose P.R. teams wouldn’t stoop to allowing us within smelling distance during most of the year, were suddenly clamoring for covers and roundtable slots or, if their race was tight, any coverage, really. “What can we do?” was a not-infrequent question.

That’s despite the fact that we were never able to prove that the media attention we offered was actually meaningful to their campaigns.

In fact, THR’s website traffic suggested the opposite: With rare exceptions, the awards coverage during the Oscar and especially Emmy seasons generated relatively little reader interest.

Yet it was simply accepted by the various awards consultants and campaigners that more interviews led to being “in the conversation,” and thus a better shot at earning a coveted Oscar. Hence the firehose of awards media during “Phase One” of the campaigns, when everyone and their publicist thinks they’re a contender.

Notes

I focused on the five Oscar categories with individual nominees:

Best Actor

Best Actress

Best Supporting Actor

Best Supporting Actress

Best Director

For each year from 2010 to 2024, I took all the nominees in a category and measured how often they were mentioned in four major film trades during the six-month awards window. This runs from 1st September in the year before the Oscars to the end of February in the award year, covering festival premieres, campaigning, screenings, and voting.

The outlets were Deadline, Variety, Hollywood Reporter, and Screen Daily. I also looked into tracking coverage from the LA Times and the New York Times, but their coverage of the nominees is erratic and sporadic, making the data unreliable.

For each nominee, I counted the total number of articles that mentioned them in that period and calculated their share of all nominee mentions in that category. I then compared these shares with the eventual outcomes and ran a set of statistical tests to determine whether higher visibility was associated with a greater likelihood of winning.

Glad your numbers back up what I've suspected all along. Let's hope someone realizes that a few, in depth, perspective articles help inform the public, voters included, rather than a scattershot of repeated answers to the same, "you've got two minutes, go!" interviews with every publication and influencer out there. My interview opportunities are few and far between but i turn them down if there isn't enough time to get substantive inquiry going. I don't want to waste anyone's time and hope to make it an enjoyable process for the interviewee. makes for a more interesting time for everyone.

i'd be curious about any correlation (or lack thereof) of pre-nomination press coverage translating to a nomination. There are at least a dozen viable contenders during this stage which could make trade coverage more important than when there's just five finalists.

to control for popularity, perhaps volume of google searches or wikipedia pageviews?