Does the timing of reviews predict whether a film is any good?

I tracked the timing of 175,902 critic reviews across 10,766 films to see what it signals before the opening weekend.

I think we all suspect that if a distributor is preventing critics from reviewing a movie, it’s not because they’re so pleased with how good it is that they want to make sure the critics really enjoy the anticipation of seeing it.

No, it’s because the movie stinks. And they know it. And they don’t want the rest of us to know it until a few minutes after the movie starts, once they’ve got our poorly spent money.

But this blog is not about guesses - it’s about seeing what the data reveals. Which means we have two questions to answer today:

If a movie doesn’t have advance reviews, should we use that as an indicator that it won’t be very good?

And if it is true, should we use this to decide what to see in cinemas?

Today’s topic was suggested by Matt Liebmann from Vista Group, who, despite being deep in planning their upcoming VistaCon 2026 conference, took a moment away to ask:

Is there a correlation between when a movie’s reviews are released and the box office?

I turned to the data to find out. I tracked the publication date and review score of 175,902 film critic reviews across 10,766 movies released since 2000.

Let’s start at the beginning and ask why distributors would want to delay bad reviews, which are going to come out anyway.

First, a little promo for a fellow film data Substacker - Daniel Parris...

Stat Significant is a free weekly newsletter with 24k subscribers featuring data-centric essays about movies, music, TV, and more.

When do we stop finding new music? Which TV shows got their finale right, and which didn’t? Which movies popularised (or tarnished) baby names? Subscribe to Daniel’s blog for free to find out!

The advantage of delaying reviews

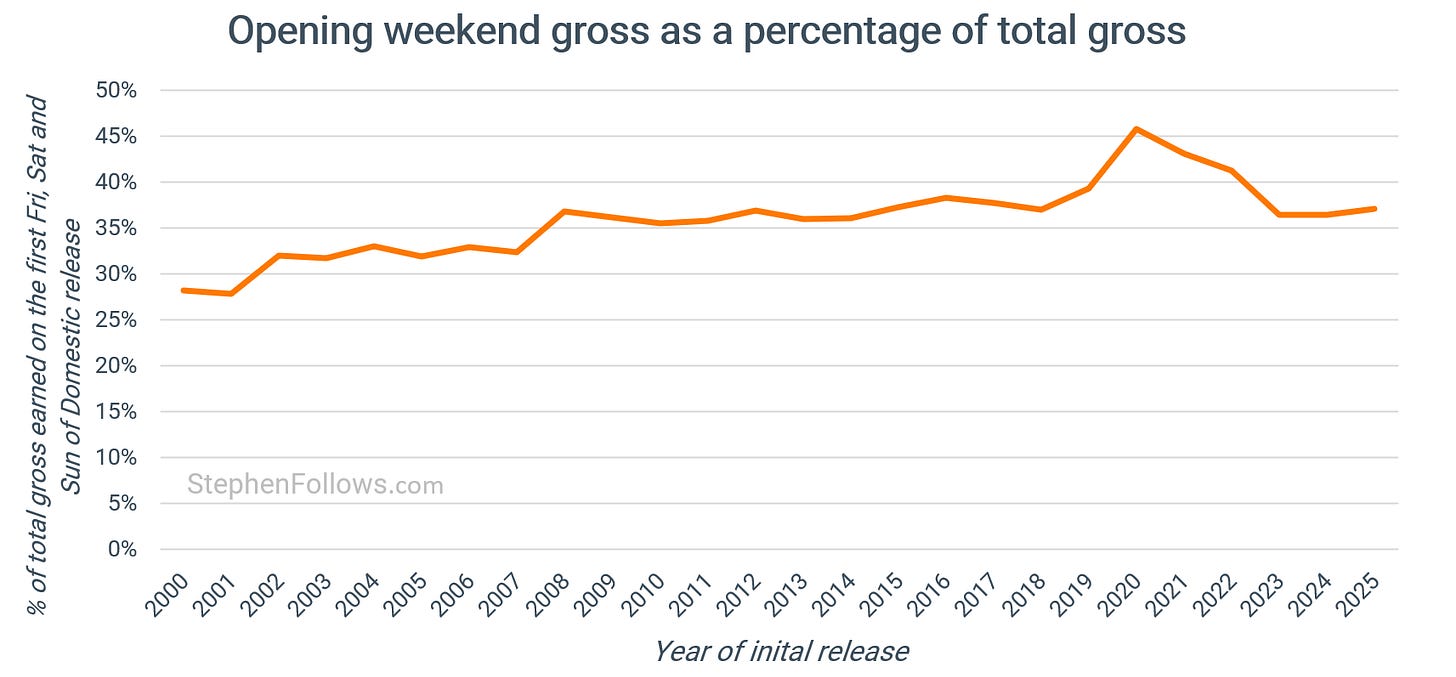

The theatrical market is built around a narrow window in which information and money move very quickly. Opening weekend still does a disproportionate amount of the work, especially for wide releases.

So if a large share of a film’s eventual box office is earned before audiences have had much time to talk to each other, distributors will want to protect that.

A 2006 study found that the quality of the movie had much less of an effect on opening-weekend box office than on overall box office gross. You could read this to say: the more time people have to learn about how good the movie is, the more it matters if it’s any good.

Another study in the Journal of Marketing found that reviews have their strongest impact early in a film’s run. Negative reviews, in particular, hurt box office performance more than positive reviews help it, but that asymmetry is concentrated almost entirely in the first week. As the run continues and audience word of mouth takes over, the effect of criticism weakens.

In other words, bad reviews are most dangerous precisely when studios are trying to maximise opening-weekend demand.

So let’s turn to the data and see if we can detect this effect in the wild.

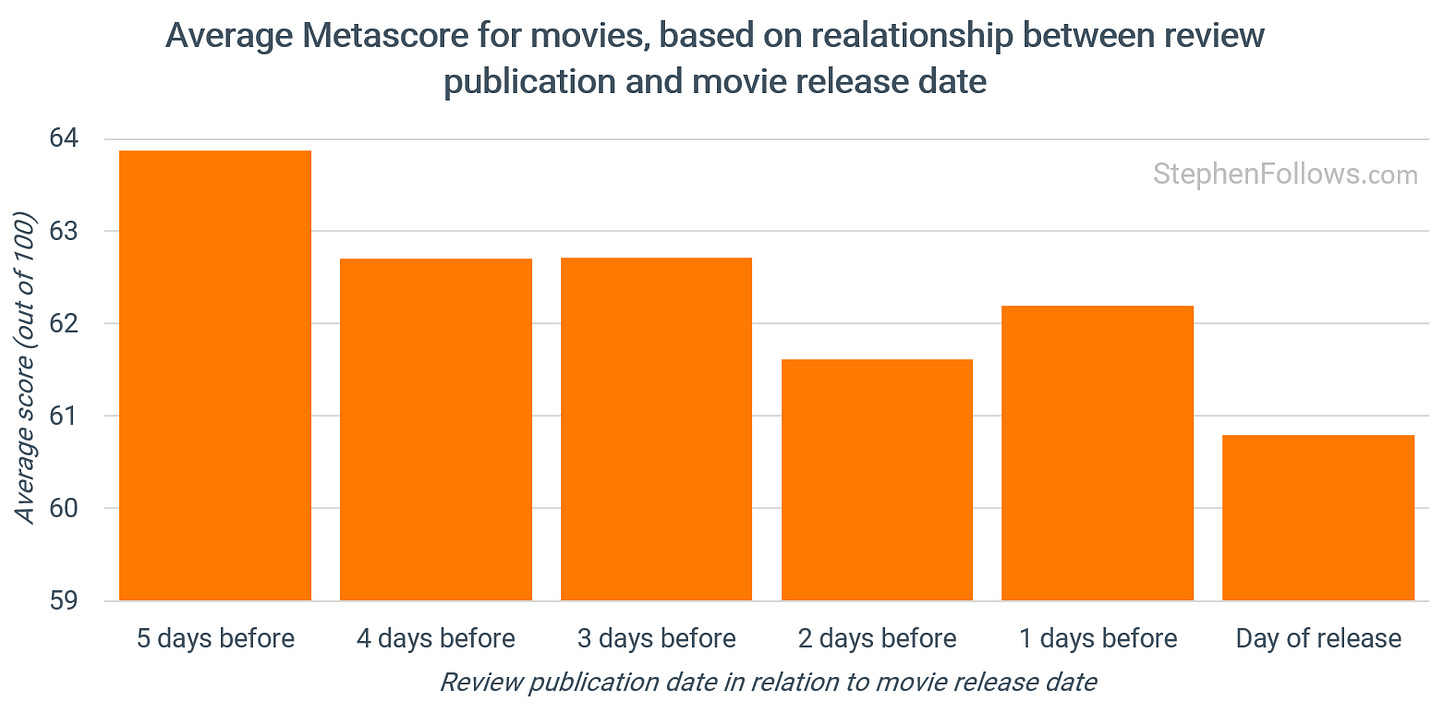

Do earlier reviews correlate with better films?

Yes.

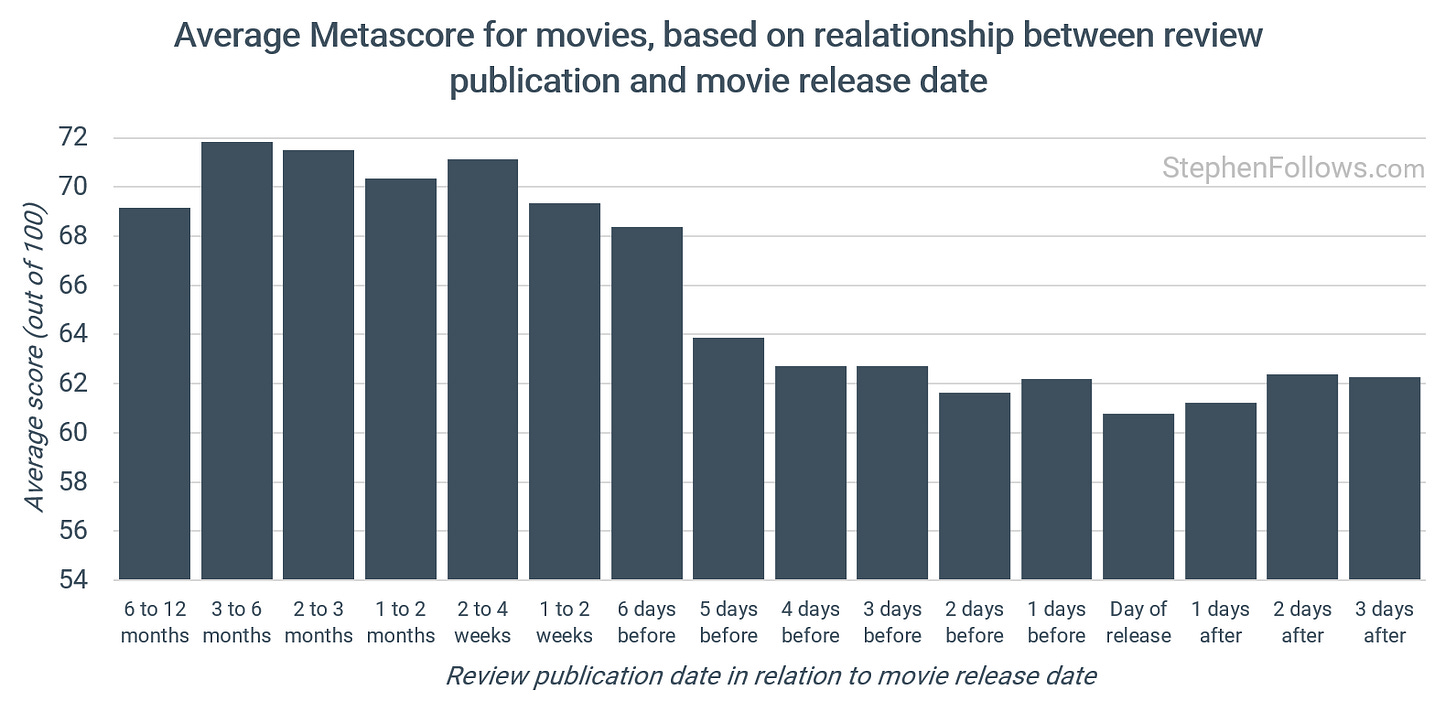

When we track the Metascore for movie reviews by the time difference between the review publication date and the movie’s release, the average score falls.

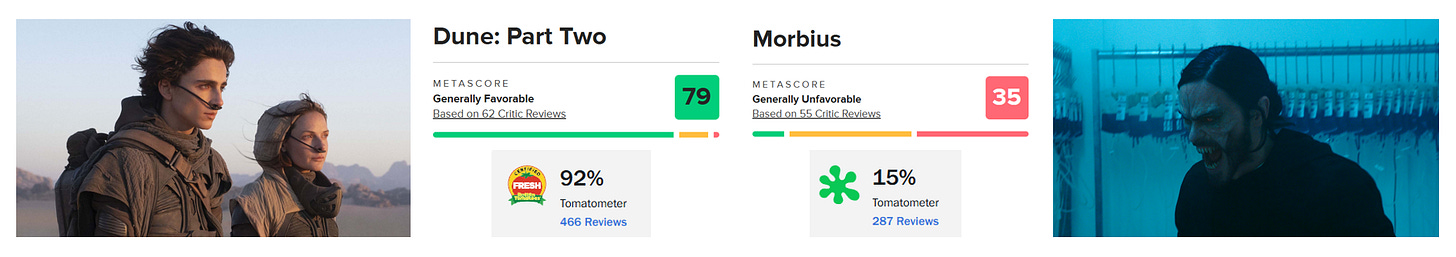

Reviews for both parts of the recent Dune duology came out well over a month before the movies were released, gaining Metascores of 74 and 79 out of 100. This built buzz and helped the movies have stellar opening weekends.

Conversely, reviews for Morbius (Metascore 35 out of 100) were embargoed right until the last possible moment, landing effectively on release. When they did appear, the response was overwhelmingly negative. The film opened on marketing and brand recognition, then collapsed once audiences caught up with the critical consensus.

Do even earlier reviews correlate with even better films?

Again, yes.

If we zoom out wider than just the week of release, we see an even stronger effect

The Metascore of movies reviewed months ahead of release clusters in the low 70s. Films reviewed in the final days cluster in the low 60s.

There are two things going on here:

Firstly, when a movie is way above average, then the senior folk at the distributor or studio will want to shout about it. In part because it’s such a rare occurrence that the sheer shock causes them to jump out of their palatial bath, run naked through the streets, shouting “Eureka! I always knew I was a genius” and also because it can form part of the marketing strategy.

Word of mouth has consistently been shown to be the most powerful force in movie marketing, so when the buzz looks good, it makes sense to lean heavily into it. The marketers will want to get as many chatty people with a platform to see the movie, in order to build anticipation. This will include “talkers“ (i.e. advance cinema screenings for the public) as well as getting professional reviewers to see it earlier.

The second big reason is film festivals. When a film premieres at film festivals, film critics get a chance to review it months before its commercial release.

In general, film festivals tend to show the better films (although not always, see point 6 here) and so it makes sense that the films reviewed early at film festivals will receive higher-than-average reviews from critics.

But even if the film is not officially “In Competition”, film festivals can be great platforms for distributors to use to gain buzz and get the word out there. Top Gun: Maverick had a glitzy red carpet premiere at the Cannes Film Festival weeks before its release, earning column inches in the celebrity-focused press and positive reviews from film critics.

So when we see reviews appearing three, six, or twelve months before release, it usually reflects a festival debut rather than a distributor taking an unusual marketing risk.

Notes

The dataset covers 175,902 individual critic reviews of 10,766 commercially released US films between 2000 and 2025, for which I found at least 10 reviews. Each review is matched to a publication date and a theatrical release date, allowing me to measure the gap between the two.

My approach weights reviews equally, without accounting for the outlets’ influence or reputation. It’s also tracking the reviews, not film averages. Both these choices will affect the numbers, but I don’t think they change the outcome.

I’m attributing almost all of the correlation here to the quality of the movie, but it’s possible that critics are punishing films (relevant reading: Do film critics punish films with bigger budgets?) because they feel snubbed from not getting a sneak peek ahead of the Great Unwashed. While it’s possible that perceptions do play a role, I very much doubt this is the core mechanism.

A point for the argument of why film festivals are an important part of the ecosystem, and also, perhaps, why we should be looking at longer theatrical windows — to protect the power of word-of-mouth! Thanks for this!

I would love to see a data study on who reviews true independent movies. Where does that happen - if at all? Is that an untapped market/readership? What happened to film criticism? etc., etc.