Which types of features films are called 'films', and which are called 'movies'?

I wanted to know if my instinct to choose ‘film’ or ‘movie’ was random so I tested it against millions of reviews. Turns out, there are clear patterns when each is used.

I write a lot of about feature films and so I often have to pick between using ‘film’ or movie’.

Fortunately, in most cases both choices are valid and I can just go with whichever seems contextually relevant without thinking too hard. One of the two just feels right.

But behind that snap decision is a whole bunch of semi-subconscious connections, correlations and prejudices, and I want to understand them a little better.

I have previously looked at which is most commonly used in the film industry (answer = film), on Reddit (movie), and how it changes around the world (USA is Team Movie, Italy is Team Film, and unsurprisingly the UK can’t pick between the two).

Today I am turning to a data from over five million reviews written by film fans online.

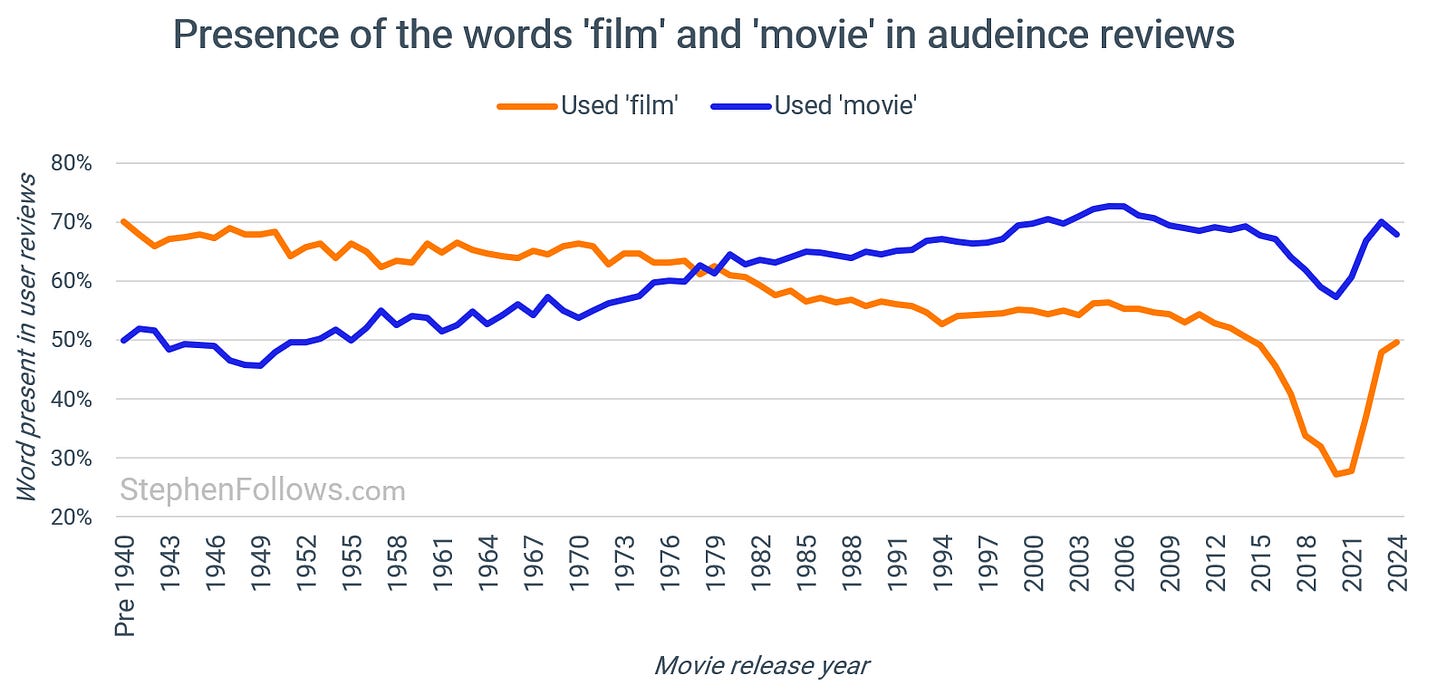

I looked to see what percentage of the reviews used either word (reviews could contain both, hence why the figures add up to more than 100%)

Over such a large dataset, some clear patterns emerge.

Which is used more often - film or movie?

When referring to films that were first released before the late 1970s, the word 'film is preeminent. For films released from the 1980s onward, movie takes the lead, and doesn’t let go.

Note: You might have spotted the strange dip for both words around the pandemic. It’s intriguing but I don’t think it’s relevant to today’s topic of film vs movie. Something for later research, me thinks.

What kinds of movies are films, and what kinds of films are movies?

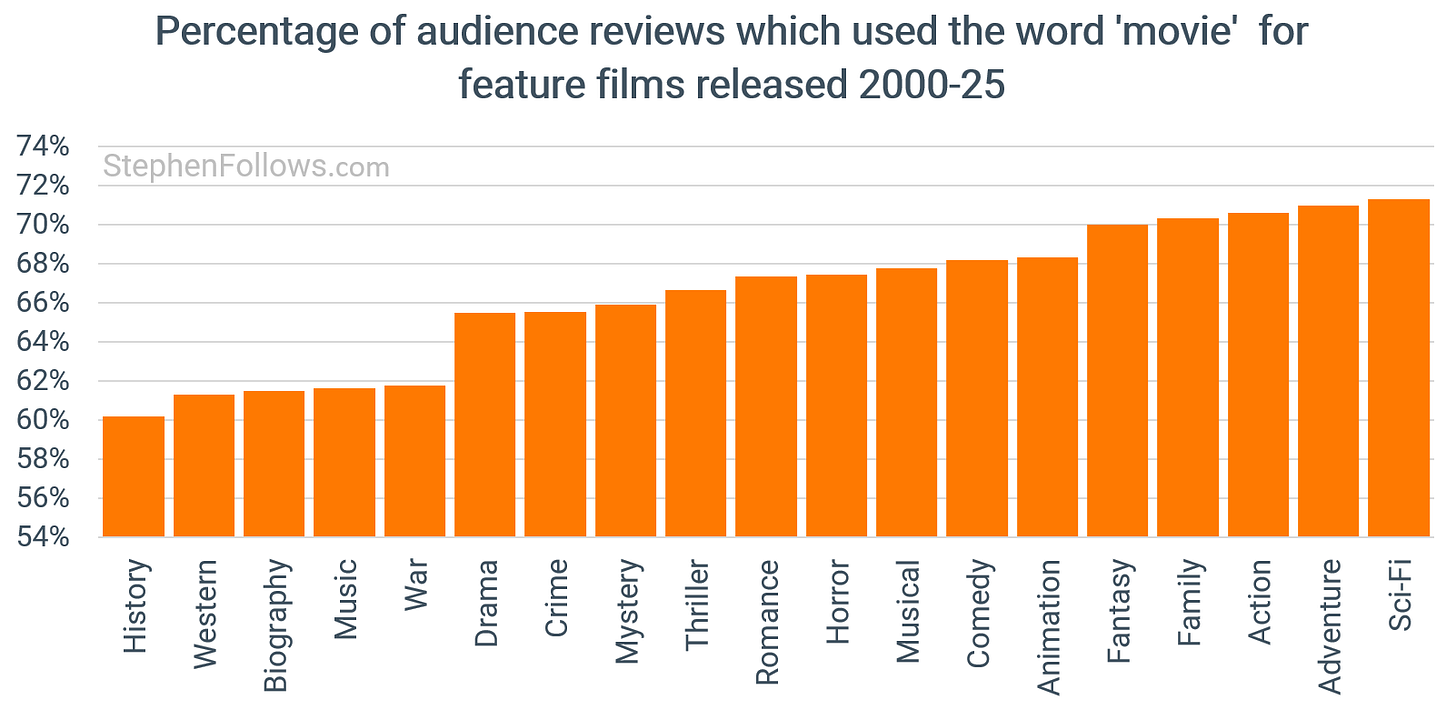

If we focus on movies released since 2000, and split them by genre, the true nature of the two words is revealed.

The projects most likely to be referred to as a ‘movie’ are those set around spectacle and light fun. Action. adventure and sci-fi top the list.

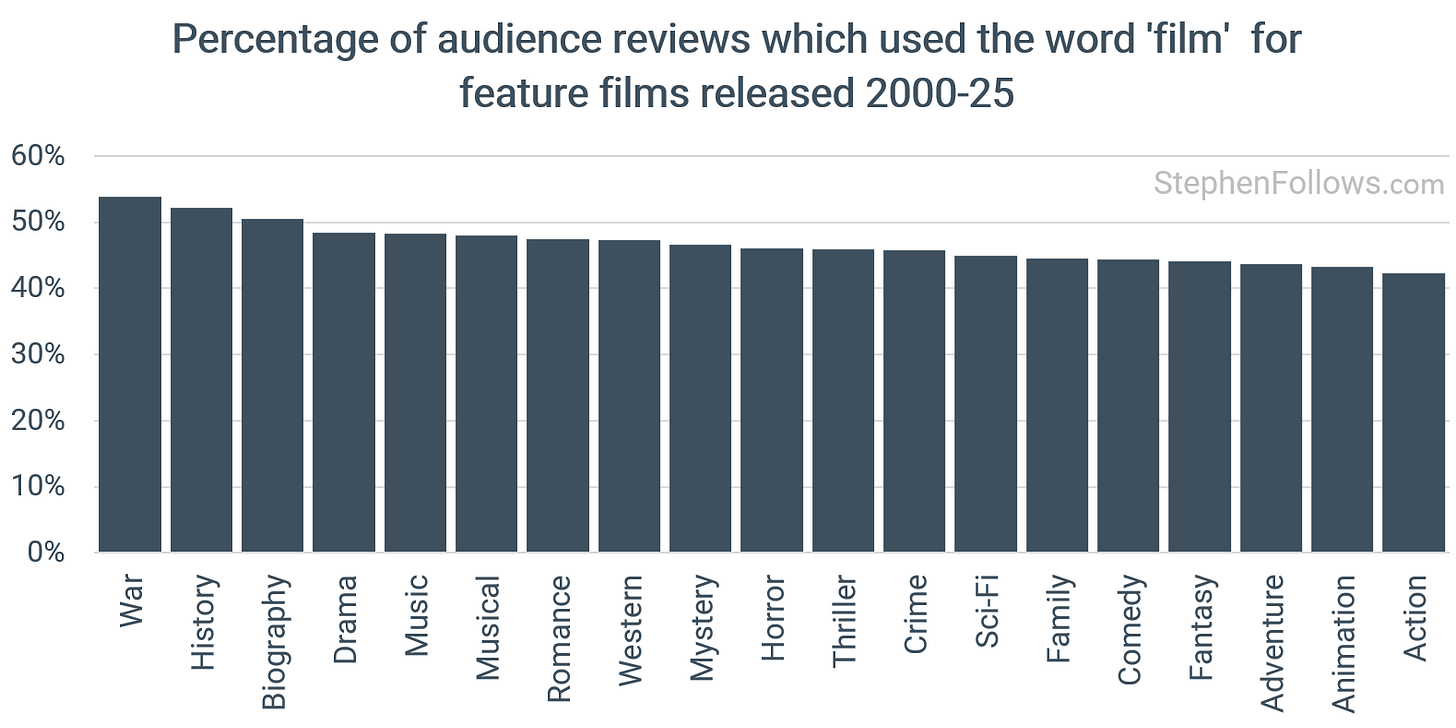

And if we look at the genres most likely to use ‘film’ we see almost the complete inverse.

The genres most likely to be called films are war, biographical, historical and dramas. The least are the ‘popcorn fare’ of adventure, animation and action.

Note: I flipped the order on the chart above, with the greatest number of uses of the word to the left, rather than the right as it was for the ‘movie’ chart. I did this as it makes the inverse similarity between the two words abundantly clear. The same kinds of genres sit to the left and to the right.

So we could say that the more fun a genre appears to be, the greater chance it has to be a movie.

Or as legendary film director Alan Parker put it in his superb book Will Write And Direct For Food…

The difference between a ‘movie’ and a ‘film is that one is scared to death of boring you for a second and the latter refuses to entertain you fort a moment.

Who prefers films over movies?

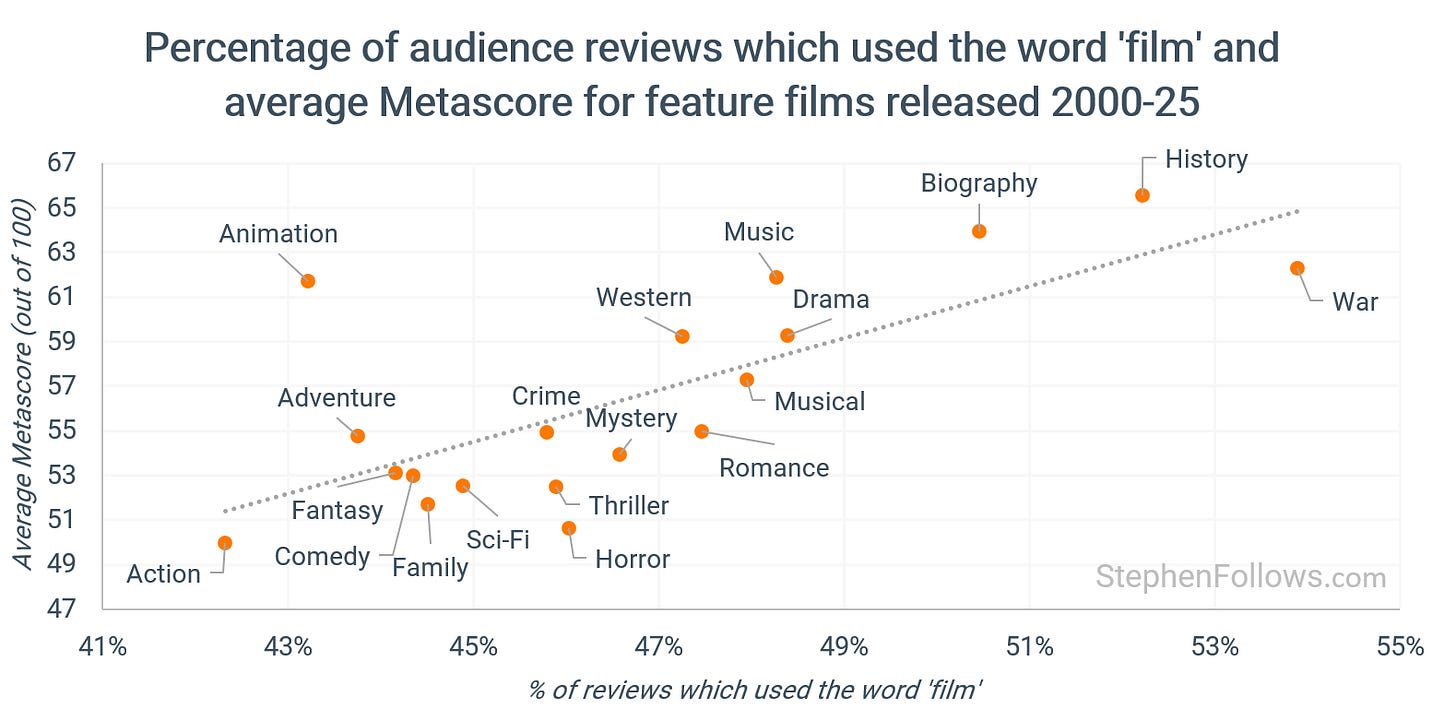

When I tracked the average Metascore of the genres against how often they are referred to as a ‘film’ we see a neat corelation.

The pattern mirrors what I found in 2016. People in the film industry preferred using “film” while the public default to “movie”. Here we see audiences reach for “film” when they feel a title sits in the high‑prestige lane, and “movie” when it reads as entertainment.

Who makes films vs who makes movies?

Given that most directors have a strong creative voice and a narrow set of types of films they choose (or are hired) to make, we can look to see who should be the poster child of each term.

The top directors most like to have their work described as a ‘movie’ are those making crowd-pleasing, formulaic, popcorn movies:

Raghava Lawrence

Anubhav Sinha

Jason Friedberg and Aaron Seltzer

Aanand L. Rai

Keenen Ivory Wayans

Rohit Shetty

S.S. Rajamouli

Malcolm D. Lee

Tyler Perry

Adam Shankman

Whereas those most likely to be producing ‘films’ are the people behind awards-bait high art:

Michael Haneke

Stephen Frears

Roman Polanski

Steve McQueen

Woody Allen

Paul Thomas Anderson

Terrence Malick

Lars von Trier

Fernando Meirelles

Park Chan-wook

Notes

The core data was gathered from a number of public sources, with the aim to sample what real people (well, people who spend their time adding reviews online, so at the very least ‘real-adjacent people’) say about projects. This obviously isn’t a precise tool but even so the patterns which naturally make sense have emerged in the data.

It’s worth having a read of my past article on the topic and geography plays a roles here. Online English language writing pulls towards “movie” in part because of the US dominance on publishing and audience.

The “top 250 directors” were selected on the basis of who had the greatest number of reviews in the dataset, and had made at least five films.

A fascinating and original piece, I would say 'Film' is used more in Europe, 'Movie' in the US obviously, but maybe Asia, Australia and New Zealand as well. Australia and New Zealand kinda following the US in many things.

However, an obvious question, why do we still call them 'Films' when no film is involved?! Not for many years and now virtually all movies and TV series are made digitally or on video. Certainly 'film' is more evocative and I guess a throw-back to the old days, but people even have 'film' credits, like, film editor, where no film touched their hands!

On a lot of entertainment shows, they're called, 'offline editors' which is more realistic, but does have a kinda downmarket feel, so I guess the more artistic 'film' just has more of a quality feel. Don't know how 'movie' fits in with this though!

Geoff