How many Hollywood movies are made outside America?

I crunched the data behind the state of "non-American" Hollywood movies, and considered how any system of American tariffs might work.

Yesterday, Donald Trump announced a plan to impose a 100% tariff on all foreign-made films. He claimed that international tax incentives were draining American productions from US soil and accused other nations of engaging in economic sabotage and cultural propaganda. In his Truth Social post, he wrote

"We want movies made in America, again!"

The statement lit a fire under an issue the industry has rarely confronted head-on. What does it actually mean for a movie to be made in America? Is it about where the cameras roll, where the money comes from, or who controls the creative vision? And how many so-called Hollywood films would actually pass the test if one were imposed?

Film production has become one of the most globalised industries on earth. Crews, financing, visual effects, post-production, and even actors routinely cross borders. Many American films are shot in Canada, the UK, or Australia. And while Trump’s proposal assumes a clear line between foreign and domestic, the modern reality of filmmaking is a blur.

Let’s see what the data can reveal about where they are really made, and what factors any American tariff system would need to contend with.

How many movies are made in America?

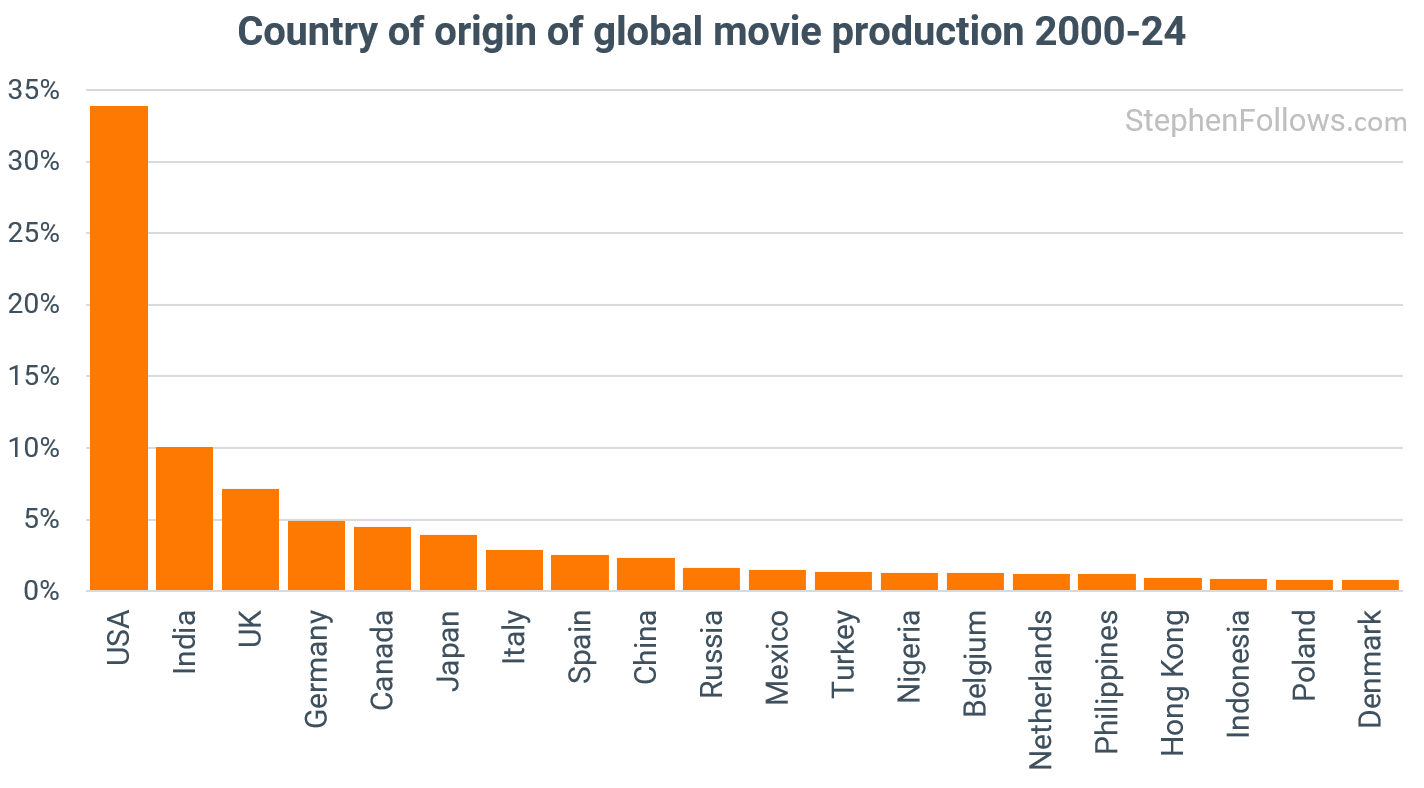

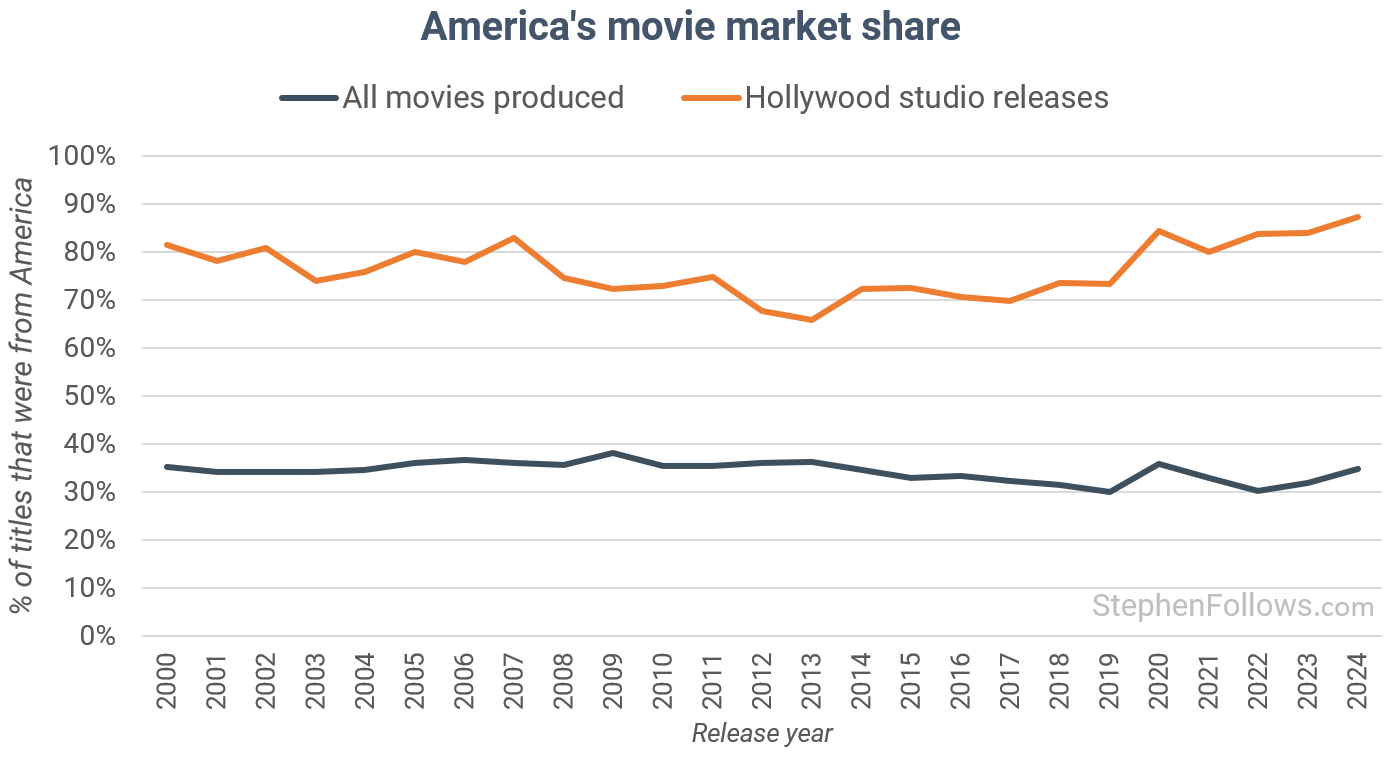

The phrase “made in America” sounds simple, but is hard to discern for most major movies. If we use IMDb’s country of origin, then around a third of global feature films could be classed as American since 2000.

If we focus just on movies from major American Hollywood studios, then that rises to more than four out of five (87.3% in 2024).

However, it’s not as simple as “American or not”. That’s because:

Films typically have multiple countries of origin. Many films today are co-productions between two or more countries. This allows them to access multiple tax incentives, funding sources, and distribution markets.

There’s no system for tracking it. There is no universal database or framework for defining or verifying a film’s national identity. IMDb allows producers to self-report, while awards bodies, festivals, and national funds each apply their own criteria. These systems often conflict, leading to different answers depending on who is asking and why.

A global supply chain. Films are made through a global production pipeline. Just like manufacturing, cinema today relies on an international supply chain rather than a single point of origin.

Streaming platforms blur boundaries further. Global streamers like Netflix and Amazon regularly commission films with no clear country of origin. A project might be developed in LA, produced by a UK company, shot in Spain, and marketed as “international content.”

American studios regularly back non-American films. Hollywood studios often finance, produce, or distribute films that are not American in origin. This can include prestige dramas aimed at awards season, international co-productions, or local-language content for foreign markets.

How do you figure out where a film is “from”?

Any tariffs would require films to have a clear national identity. Currently, the United States has no formal definition of what makes a film American. There is no certification process, no threshold of domestic content, and no single agency responsible for determining national status.

The term “nationality” can mean different things depending on who is asking and what is at stake. Festivals, awards bodies, funding agencies, and audiences all apply different criteria, and the results can vary dramatically (I’ve added some controversial examples at the end of this article).

Many people first wonder in which country the actual filmmaking took place. Shooting locations are, in theory, easy to identify. A film either rolls cameras in a place or it does not. But this becomes complicated when productions are split across multiple countries or use remote teams.

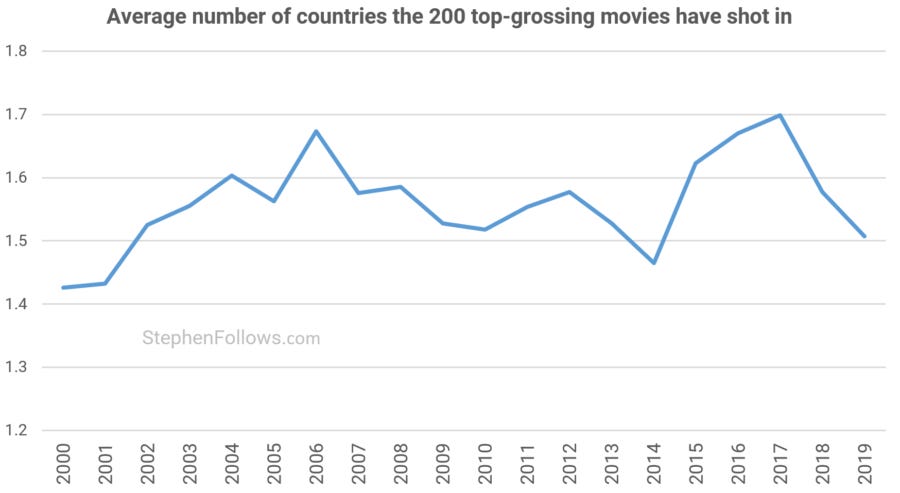

When I looked at this a few years ago, I discovered that the average top-grossing movie is shot in 1.6 countries.

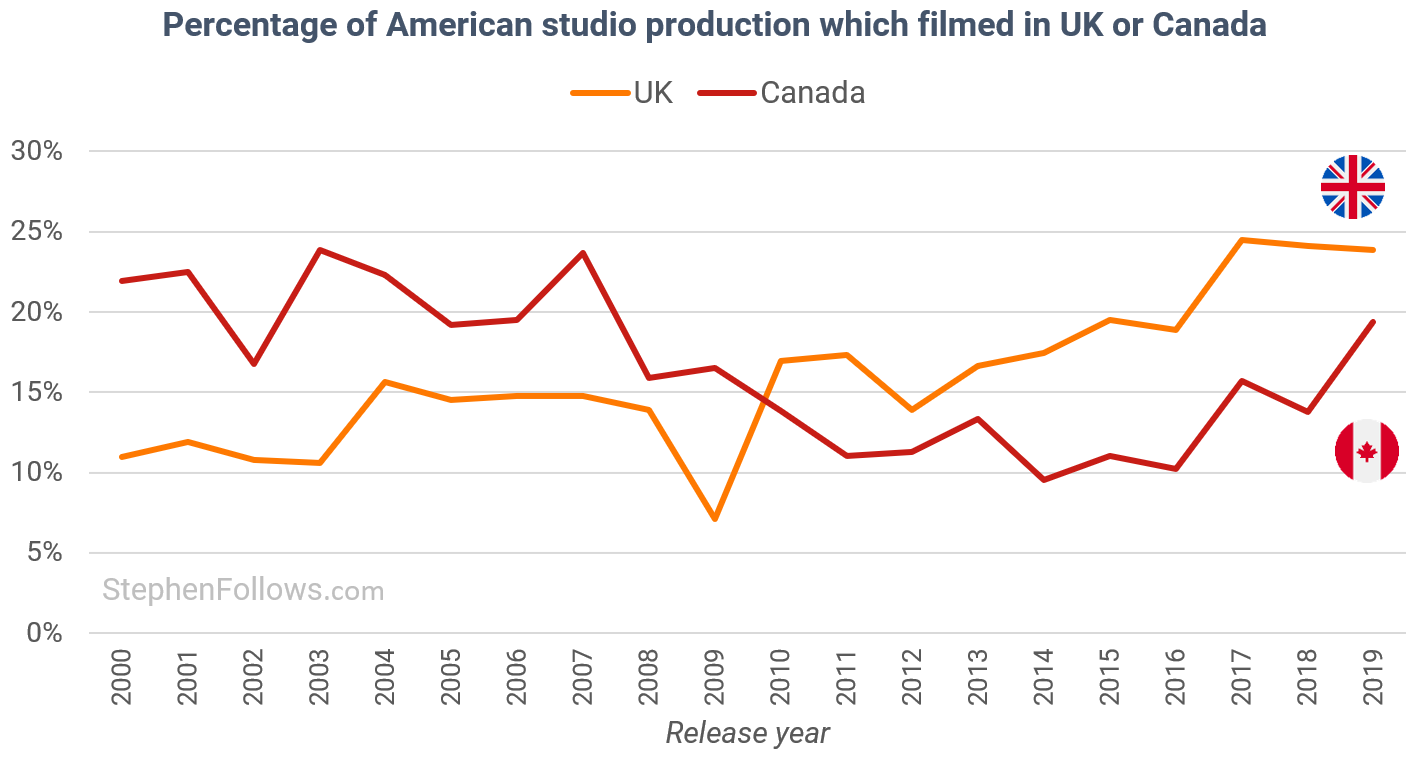

The UK and Canada are the top foreign locations for studio productions. The chart below shows the percentage of movies made by Hollywood studios, which have America as a country of origin on IMDb, that had at least one day of filming in the UK or Canada. As you can see, it’s significant. In 2019, 23.9% of such productions were shot in the UK, while for Canada, the figure was 19.4%.

These shoots are not always weighted equally. One country may host a few days of aerial photography, while another carries the bulk of the production. Some offer studios and crews. Others offer tax rebates or natural landscapes. Some supply specialist services like underwater filming or digital doubles. Measuring a film's production true footprint by location would require weighting the contribution of each territory.

Another method is to look at the primary production company. Some major festivals, such as the Berlinale, define a film’s origin based on the registered office address of its main production entity. This is easy to verify and administratively convenient. But it often fails to reflect the broader picture. Many films are made through international co-productions, with creative and financial input coming from multiple sources. Pinpointing the “main” producer is rarely clear-cut.

Official co-productions bring their own rules. Countries with bilateral or multilateral treaties often allow a film to qualify as “national” in more than one country. This provides access to local tax breaks and funding, but only if strict criteria are met. These include minimum financial contributions, nationality requirements for key crew, and points-based systems assessing cultural relevance. A film can pass as “French” under one set of rules and “Canadian” under another, depending on how the co-production is structured.

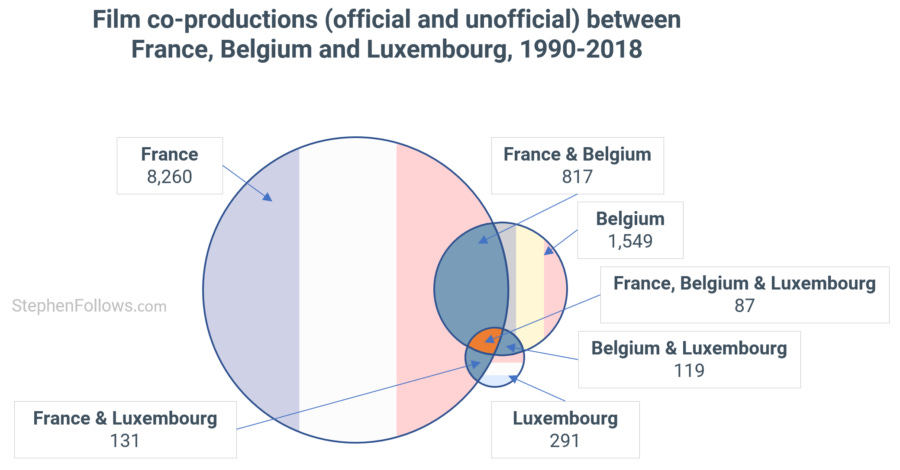

I looked at this topic a few years ago here Which countries most commonly team up to create film co-productions? As a good example, see below for the complicated relationship between movies made in France, Belgium and Luxembourg.

You could choose to follow the money. Countries contributing the majority of the budget are often assumed to be the film’s home. This logic drives many decisions around subsidies and eligibility for public funding. But modern films are rarely funded by a single source. Budgets may include pre-sales, equity investors, tax rebates, and soft money from several territories. Even identifying where most of the money comes from can be difficult, especially if financing is routed through holding companies or structured to meet treaty obligations.

The director’s nationality is sometimes used, particularly by critics and audiences, but is rarely decisive in formal classifications. The Oscar-winning Brokeback Mountain was directed by Ang Lee, who is Taiwanese, but no one questions its status as an American film. In contrast, Caché, directed by the Austrian Michael Haneke, was submitted to the Oscars by Austria but disqualified because it was in French. The Academy ruled that the language did not match the submitting country. This led to widespread criticism and a later rule change.

Language is another marker, particularly for awards. The Academy Awards’ International Feature Film category requires that more than 50% of the dialogue be in a non-English language. This rule disqualified Nigeria’s Lionheart, despite English being one of Nigeria’s official languages. Austria’s Joy, a film about Nigerian immigrants spoken in English and Pidgin, met the same fate. These decisions exposed how poorly the rules reflect the linguistic realities of post-colonial societies.

Sometimes the cultural content or aesthetic feel of a film shapes how it is perceived. A film may be classified as American, French, or Korean because of its themes, settings, or cinematic style. This kind of informal identification can matter a great deal to audiences and critics. Sergio Leone’s Westerns feel American to many viewers, despite being Italian productions. In other cases, films are labelled according to their narrative setting rather than their production background.

Then there is the question of post-production. Visual effects, editing, sound mixing, and colour grading are often done in countries that never appear in the credits as production partners. For example, a film shot in the UK may be finished in India or New Zealand, using remote teams and cloud-based pipelines.

Finally, the rise of AI in filmmaking is going to upend many of the foundational principles on which the current thinking is based on. If a shot is generated by a British person, living in France, on a Taiwanese computer, using a Chinese artificial intelligence model, trained on global training data, running on a Canadian server… then I’m lost already!

What are you trying to protect?

One aspect of the debate around country of origin is - what are you trying to protect? Three aspects to the film business could be prioritised in any scoring system of movie nationality:

The economy. Movies spend vast sums of money and thereby contribute to a country’s economy, both directly (i.e., employing people, buying consumables, renting locations, etc.) and indirectly (i.e., the multiplier effect of the employees buying things, paying taxes, etc.).

The industry. A product can employ thousands of people directly and via all the parts of the industry servicing the distribution, marketing, and release of those movies.

The culture. Movies are a major cultural export, showcasing a country and telling the stories of its people.

Let’s quickly think about the challenges in building a system to protect each of these priorities.

Priority #1 - Following the money

A simple method for tracking money would be to look at the source of the funds. However, that would not achieve President Trump's stated goals, as Hollywood movies are mostly made with American money already - it’s just that they spend a lot of that outside the US.

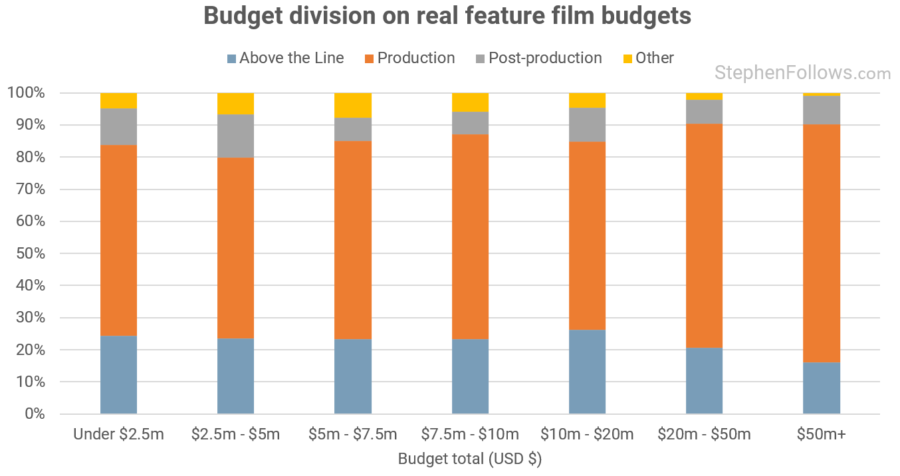

Another method for an economy-focused system would be where the money is spent. This would have a heavy correlation with where the majority of the filmmaking was conducted, as between half and three-quarters of a film’s budget is spent during filmmaking.

While the UK does not pay close attention to the amount spent to determine whether a film is “British” or not, the figure becomes incredibly important when calculating how much of a tax rebate the production will receive. In response, US studios set up Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs), which are British shell companies through which to spend the movie’s funds. This means that a British company is spending American money to employ people of many nationalities.

Priority #2 - Protecting jobs

Alternatively, if we were to value the industrial side of the film business (i.e., keeping jobs in America), we could focus on the nationality of the people who make the film and/or where they live.

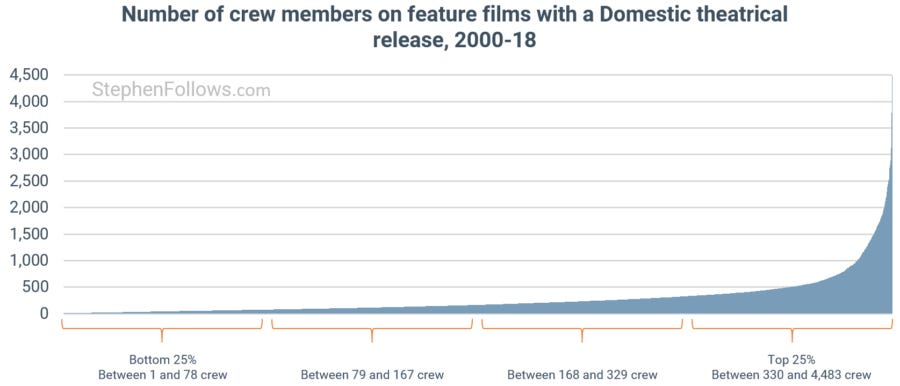

Hollywood productions typically employ thousands of people in their creations, and they have a power law in their distribution.

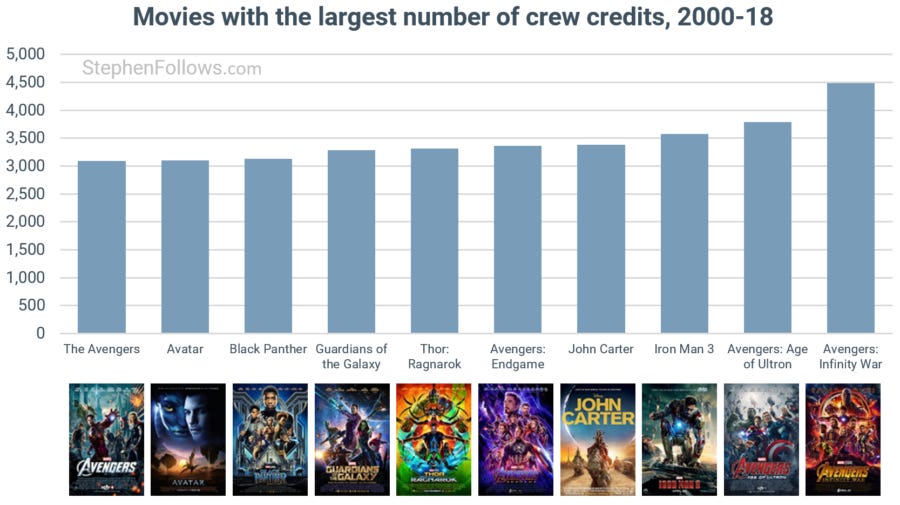

When I examined this a few years ago, I discovered that 4.3% of all movie credits were for Marvel movies.

The challenge here will be determining the weight of each person’s contribution. Most nationality-based scoring systems for movies focus only on the leading cast, main creatives (i.e. writers, producers, and directors) and heads of departments.

Priority #3 - Protecting Culture

Hollywood has played a massive part in spreading the American ideal and values around the world. Therefore, you could set up a system which rates a film’s “Americanness” based on what’s in the film - the characters, stories, settings, etc.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to StephenFollows.com - Using data to explain the film industry to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.