What makes people never want to rewatch a great film?

Looking at the data behind which films appear on user-generated lists of 'Movies which are awesome, but I don't ever want to watch again' reveals what feeling audiences never want to return to.

If you ask most people about Darren Aronofsky's drug-fuelled mad 2000 classic movie Requiem for a Dream, they will say the same thing:

Wow, such a great movie. I’m never watching it again.

So much so that it has become shorthand among film fans for ‘A great movie that doesn’t attract repeat viewing’.

When you stop to think about that concept - an objectively great movie that people avoid - it’s quite kinda strange. If you like watching great movies, and you think that Requiem for a Dream is indeed a great movie, why wouldn’t you want to watch it again?

Added to that, there are loads of mediocre and bad movies that we all collectively choose to re-watch, despite knowing (either from experience or their reputation) that better movies are available.

I’m going to tackle the notion of “re-watchability” in a future article, but today I’m going to focus on the following question:

What is the element that, when present in a great movie, means that audiences never want to watch it again?

To do this, I built up a dataset of 19,821 movies which appeared at least once on 530 user-created lists on Letterboxd, centred around the theme of ‘Movies you’ll only watch once’. I then narrowed down to the most oft-cited movies and their ratings.

In doing so, I think I have worked out what it is that is driving the ‘One and Done’ approach to viewing some great movies.

The archetypal one-time gem

Let’s start by studying our principal example to ensure we know what we’re looking for.

Requiem for a Dream was directed by Darren Aronofsky and adapted from Hubert Selby Jr.’s 1978 novel of the same name. It follows four characters in Brooklyn whose lives gradually unravel through different forms of addiction.

The film is about one’s options narrowing and the inevitability of a bad outcome, even as the characters seek escape. The way it’s shot only adds to this, with lots of repetition, escalation, rapid editing, extreme close-ups, and an insistent score to reinforce the sense of momentum without release.

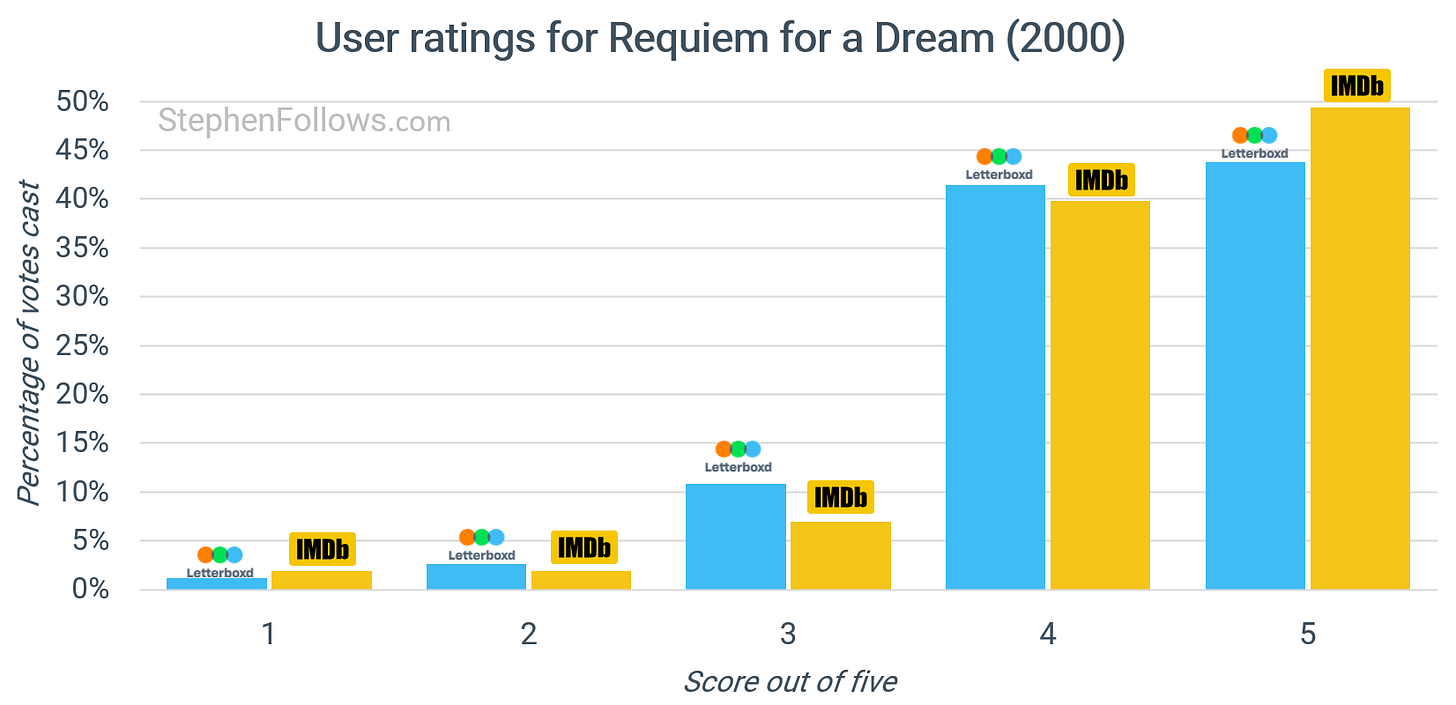

The movie consistently gets high ratings from people of all types.

Critics give it an average of 71 out of 100 on Metacritic.

80% of the 128 critics on Rotten Tomatoes gave it a positive review.

43.8% of the cinephiles on Letterboxd who rated it gave it 4.5 or 5 out of five.

75.9% of IMDb users gave it a rating of 8 or higher out of 10.

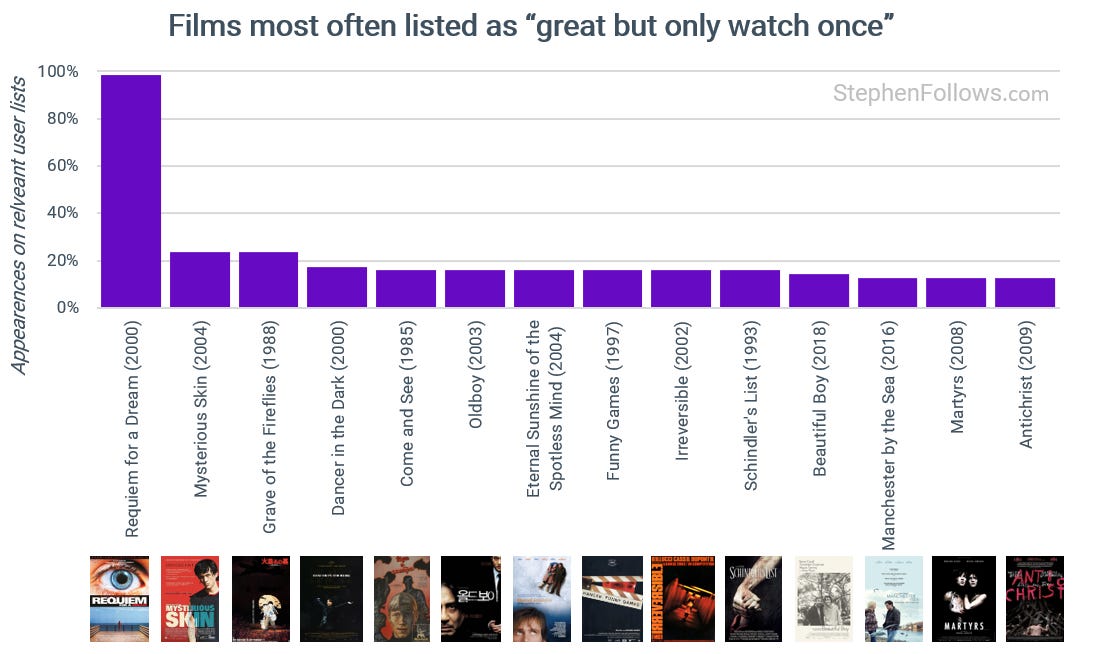

Despite its universal acclaim, when I built a list of Letterboxd user lists along the lines of ‘great films you don’t rewatch’, Requiem for a Dream appeared on 99.2% lists.

That’s right - it seems almost impossible to make a list of one-time masterpieces and not include Requiem for a Dream. The next most frequently mentioned films were way behind, and were:

Mysterious Skin (2004)

Grave of the Fireflies (1988)

Dancer in the Dark (2000)

Come and See (1985)

Oldboy (2003)

Funny Games (1997)

Irreversible (2002)

Schindler’s List (1993)

Beautiful Boy (2018)

Manchester by the Sea (2016)

One theme to ruin them all

I wanted to see if I could deduce a theme running through the long list of movie titles.

My first thought was bleak intensity. Requiem for a Dream is exhausting, bleak, and emotionally punishing.

But when I looked at what made the films on the list stand out, there didn’t seem to be any difference in this regard from many other movies.

Many violent, upsetting, or emotionally heavy films attract repeat viewings, with some even becoming comfort watches for certain audiences.

The Shining (1980) has sustained dread, violence, and psychological collapse.

Alien (1979) is claustrophobic, violent, and relentlessly tense.

Se7en (1995) is so bleak - to the extent I think many people forget just how grim it is until they rewatch it. (Not to mention nihilistic).

Jaws (1975) has sustained dread, violent deaths, and existential fear.

Rosemary’s Baby (1968) is all about intense paranoia and violation.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) is relentless and stressful.

So I don’t think that bleak intensity alone reliably indicates whether people come back.

And then I found a thread which ran through many of these one-and-done classics..

Powerlessness.

What Requiem for a Dream does so well is place the viewer in a position where effort and insight offer no protection. The film does not invite you to anticipate improvement, recovery, or escape. Each character moves forward with a sense of inevitability, and we as the audience are carried along.

Unlike bleak, intense films such as The Shining, Alien, Se7en, or Jaws, knowing where the story ends does not make the experience easier. With those films, as we become more familiar with them, we experience an added sense of orientation and control. Our knowledge of the movie helps us turn fear into anticipation, making it manageable.

The opposite applies to films like Irreversible, Come and See, Dancer in the Dark, and Grave of the Fireflies. In each case, knowing what is coming does not provide comfort or control. It removes any remaining distance. The outcome is fixed, the damage is unavoidable, and we are required to sit with that knowledge during the movie.

So that’s my theory - great films that people don’t want to re-watch often elicit an intense feeling of powerlessness in us.

Notes

The user-generated lists I gathered for this research all had two criteria:

They claimed to contain films that were good, high quality and/or admired (which I then verified via user ratings); and

Were films the author would not want/choose to watch again.

To give you a favour, here are a few:

Amazing, but never again

Best movies that I’ll never watch again

Great films I’ll never watch again

Movies everyone should watch once that I’m never watching again

One-Time Masterpieces

The language people use to name and describe these lists is fascinating. They fell into three categories

Refusal. This was the “Never again” type, which implied that the author was adamant they were not going back.

Once only. This summed up the ‘single viewing’ perspective in a fairly neutral way.

Must see. This was the smallest group, but still present. They framed it almost as a duty to watch these movies.

I feel the same about the ones you listed EXCEPT Eternal Sunshine. Both my wife and I watch it at least a couple times a year. It’s definitely a tragic story but it lands on hope —not sure why but it’s almost a comfort movie for us.

Because many it wasn't a great film after all?