What modern movie franchises can learn from the enduring success of The Lord of the Rings

The Lord of the Rings remains rewatchable because it's accessible to all, feels whole, remains timeless, and is perfectly crafted to make cinema love it.

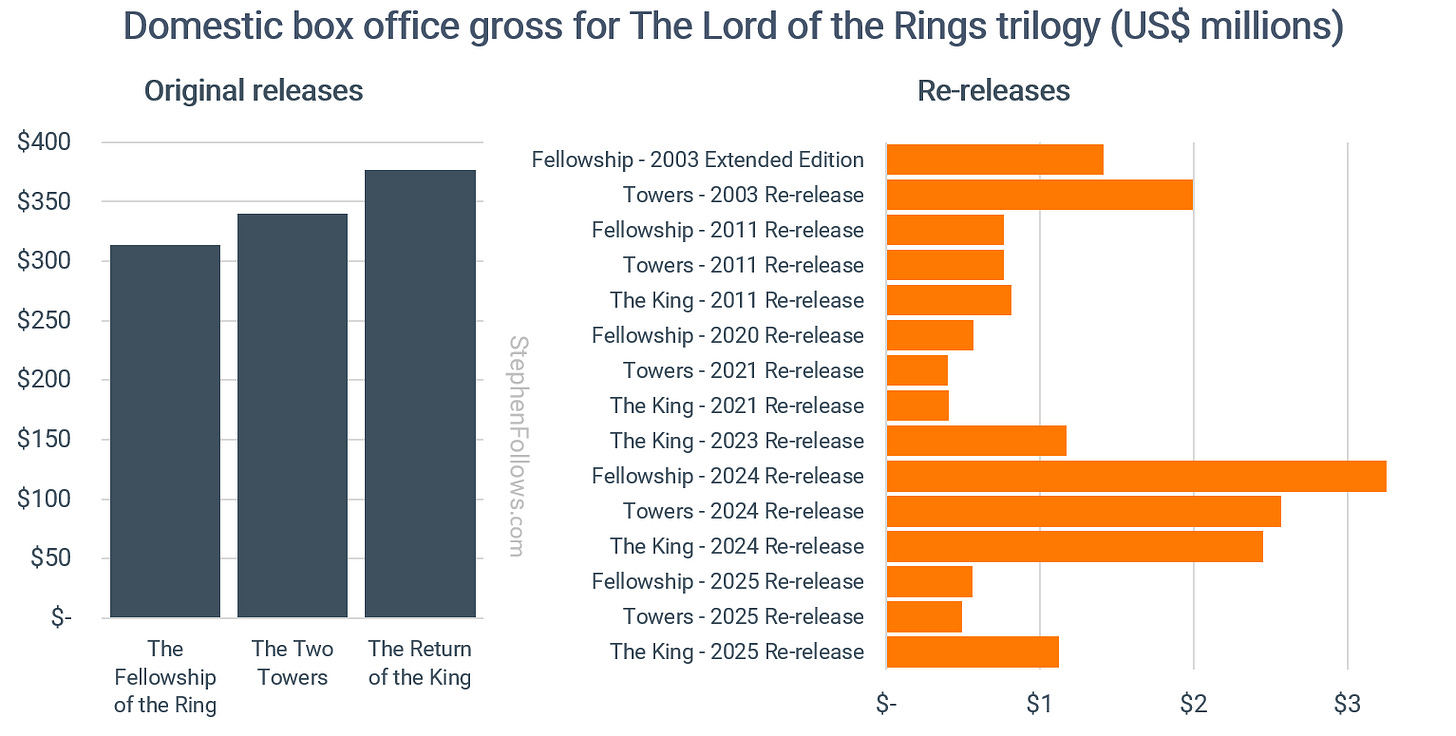

This month, the 25th anniversary of The Fellowship of the Ring has brought all three extended editions back to cinemas again, many in IMAX. The box office grosses for last weekend looks to be north of $6 million in North America.

Not only are these films almost a quarter of a century old, but many of the people who will pay to see them in 2026 will have already done so when the same films were re-released in theatres in 2011, 2024, and 2025, not to mention the ad hoc marathon screenings which regularly sell out.

Before 2026, the re-releases have grossed almost $19 million in the US alone.

Why can these films still draw a crowd?

What is it about this particular trilogy that means that so many people are willing to return to cinemas and re-watch movies they know so well? We don’t see the same love for early-2000s bedfellow tentpole trilogies, such as The Matrix, Spider-Man, Pirates of the Caribbean, or the Bourne trilogy.

I was asked by Ben Stevens from The Sunday Times what modern franchise movies can learn from The Lord of the Rings’ enduring legacy. I came away with seven factors:

It’s complete

It’s sincere

It’s very attractive to cinemas

It’s accessible

It hasn’t changed

It’s timeless

It’s family-friendly

When The Fellowship of the Ring opened in December 2001, it was the first chapter in a high-risk adaptation. All three films had been shot concurrently in New Zealand on a combined budget of over a quarter of a billion dollars. Peter Jackson, then best known for horror and splatter comedies, was overseeing a fantasy epic spanning over 11 hours of screen time. It could have collapsed under the weight of its ambition.

Instead, it became a global landmark. The trilogy earned nearly $3 billion worldwide at the box office. The Return of the King alone grossed over $1.1 billion and swept the Oscars with 11 wins. Across all three films, the trilogy received 17 Academy Awards and more than 100 nominations across major ceremonies. It remains the most decorated fantasy franchise in cinema history.

But why does it keep successfully coming back to movie theatres time after time?

Here’s why…

1. It’s complete

The story within the Lord of the Rings trilogy is neat and delivers narrative closure. Frodo’s journey ends in separation from the world he saved, Aragorn’s coronation marks the return of human rule, and the Fellowship dissolves and does not reform. The resolution is final, without cliff-hangers or post-credit sequences that undermine the emotional catharsis.

This is due to more than just the source material. All three films were produced as a single, continuous project rather than as a sequence of individual instalments. Having a single 14-month shoot allowed the same team to manage script development, set construction, visual effects, and character progression across the entire trilogy.

Director Peter Jackson said of the schedule:

So one day we’d be shooting a bit from The Fellowship, then that would be on Monday. On Tuesday, we’d shoot a scene from The Two Towers, on Wednesday, back to Fellowship again, on Thursday to The Return of the King. So it was just one film really for us.

Planning the entire story upfront meant that narrative and emotional arcs could be completed with purpose. All this helped to create a sense of cohesion that is difficult to replicate when films are developed one at a time.

You don’t need to know anything when you start the first movie, and everything is tied up by the close of the third - a very pleasing viewing experience.

2. It’s sincere

The trilogy’s emotional register is direct and unironic. Characters speak plainly about fear, courage, loyalty and hope. There is no distancing from the material, no comic relief that cuts the weight of the moment, no genre-savvy dialogue to reassure the audience that it’s all just a bit of fun.

The same tone is carried through to the score and performances, resulting in scenes that continue to resonate even for viewers who have seen them dozens of times. This is worlds away from the knowing tone of most scenes in most Marvel movies.

As Rodger Ebert put it in his review of the first film:

The Ring Trilogy embodies the kind of innocence that belongs to an earlier, gentler time. The Hollywood that made “The Wizard of Oz” might have been equal to it.

That earnestness has given the trilogy an unusual afterlife in serious settings. Lines from Gandalf and Sam are quoted in wedding speeches, graduation cards and memorial services. They circulate on social media with minimal alteration, used to anchor real-world emotions rather than parody them.

3. It’s very attractive to cinemas

The trilogy was never built as repertory cinema, yet it behaves like it was. Everything about the creative storytelling, through to its commercial package, makes it perfect for exhibitors seeking an event title that audiences already understand.

The extended editions run for roughly 11 hours, which is long enough to justify premium pricing and make a screening a day out. It is also short enough to schedule without breaking the building. A cinema can sell it as a Saturday marathon and still programme a late-night title afterwards.

The films also come with built-in intermissions. Each instalment has a clear endpoint and a clear restart point. That matters for audience comfort and for front-of-house operations. It gives cinemas natural windows for cleaning, food resets, late seating, and staffing changes without disrupting the event.

Just as importantly, the trilogy does not require external knowledge. Viewers do not need to have watched ten earlier titles, a streaming series, or a spin-off to follow the emotional logic. That makes the audience pool wider. It also makes marketing simpler. The poster can promise “all three films” and the proposition is complete.

Most franchise libraries do not offer this. MCU films rarely work as standalone repertory programming because their meaning is often tied to continuity. Harry Potter works as an event, but eight films pushes it into a multi-day commitment that many venues cannot spare and many audiences will not schedule.

The Lord of the Rings sits in the sweet spot: three films that feel substantial yet also manageable for cinemas.

4. It’s accessible

The Lord of the Rings asks very little of the viewer in advance. You can begin the trilogy knowing nothing about Middle-earth and still follow the story with ease. There are no required prologues, prequels or encyclopaedic guides. The films do not rely on prior knowledge to generate meaning. Everything you need to understand (about the Ring, the stakes, the people involved, etc) is introduced clearly and carried through to resolution by the end of the third film.

By contrast, many Star Wars movies open with dense prologues about trade disputes or galactic politics, and the significance of characters or conflicts can depend on knowledge from previous films or external media.

As well as being accessible from the start, The Lord of the Rings trilogy supports deeper engagement if viewers want it. For those who want to look further, there are layers of history, language and symbolism available to explore. There are meaningful maps, lineages, and pace names, but none are mandatory.

Middle-earth reveals itself in proportion to the attention given, and does not punish viewers who are simply there for the story.

5. It hasn’t changed

The trilogy exists in two forms: the original theatrical cuts and the extended editions. Both were completed under the same creative team, with the same actors, score and effects. Since then, nothing has been added or revised. There are no special editions, no alternate cuts, no retrospective tinkering with the visuals or pacing. The films remain exactly as they were when first released.

That stability has helped preserve them as cultural landmarks. Audiences returning to the trilogy know what they are getting. The look, tone and rhythm of the films have not shifted to match new trends or technologies. They still reflect the choices made at the time, and that gives them a sense of integrity.

Other major franchises have treated their back catalogues as mutable. Star Wars has been repeatedly re-edited, with new effects layered onto old footage and changes to character dynamics that alter tone.

6. It’s timeless

Many of the trilogy’s current viewers were not born when The Fellowship of the Ring arrived. The films have moved into the category of stories that get handed down, watched with children, and revisited on a schedule.

Part of that is theme. Sacrifice, courage, friendship, mercy, and the temptation of power remain legible even when a viewer forgets the plot mechanics. The stakes sit at the level of values rather than references.

The other part is that the trilogy does not feel like a movie limited by the era in which it was made. The mix of real-world sets, world-class miniatures, and integrated visual effects means it stood apart from the “this is what CG looked like back then” feeling that often accompanies a lot of early-2000s spectacle, such as:

The Mummy Returns (2001) has a lot of early-CG creature work that now looks shockingly poor.

Star Wars: Attack of the Clones (2002) has a digital look and compositing style that firmly places it in the early 2000s.

The Matrix Reloaded (2003) tried so hard to be cutting-edge that it now looks tired.

Sometimes it’s more subtle than just ‘bad VFX’. Spider-Man (2002) has a bright, pre-MCU tonal register that marks it as an early-2000s movie.

This is carried through into the editing, too. The trilogy’s big sequences have clear spatial logic and a steady rhythm, and do not rely on hyperactive cutting or frantic escalation to keep attention. That makes them play less like an action product of 2001–2003 and more like a self-contained myth with its own pacing.

7. It’s family-friendly

Despite its darkness, the trilogy avoids many of the elements that routinely make modern tentpole franchises inaccessible to families. There is no nudity, no drug culture, minimal profanity, and very little humour rooted in crudeness. Its violence is intense but not prurient, and its fear is mythic rather than exploitative. For many parents, this places The Lord of the Rings in a rare category: films that are serious, frightening and emotionally demanding, yet still broadly appropriate for shared viewing.

This is not a given for large-scale studio franchises. Fast & Furious evolved into a global spectacle but is steeped in criminal economies, drug-running origins, and an increasingly aggressive tone that rarely plays well for younger audiences. Blade Runner and Blade Runner 2049 are prestige science fiction landmarks, but their worlds are saturated with drug use, sexual violence, and adult despair. The James Bond franchise, even at its most cartoonish, is inseparable from sex, alcoholism, and casual brutality. Even ostensibly comedic franchises such as Deadpool or The Hangover are built around material that actively repels family viewing.

What distinguishes The Lord of the Rings is not that it is “for children”, but that it does not require adult content to sustain scale, seriousness or emotional weight. Its appeal spans generations without being softened or sanitised. That makes it easier to pass down, easier to revisit collectively, and easier for cinemas to programme for broad audiences.

A franchise that parents are comfortable introducing to their children has a longer cultural half-life than one that must be rediscovered on its own.

Notes

I referenced Rodger Ebert’s review of the first film to make a point about the story’s timeless innocence. A longer quotation from the review would be:

The Ring Trilogy embodies the kind of innocence that belongs to an earlier, gentler time. The Hollywood that made “The Wizard of Oz” might have been equal to it. But “Fellowship” is a film that comes after “Gladiator” and “Matrix,” and it instinctively ramps up to the genre of the overwrought special-effects action picture.

Ebert is suggesting that the film did not live up to the true innocence of the books, but I disagree. Since then, twenty years of ever-larger, ever-louder Hollywood movies have ramped up the relative innocence of the movies in modern eyes, closer to the point he was making about the books. So I hope Roger will forgive me for making a point with his review, which is only somewhat the point he initially intended!

Great article and I agree with almost all of it. The one omission is that the further observation “it’s authentic” could be added. By that I mean it feels entirely integrated with the tone of the source material. As such it carries the original fan base (which is passionate and large).

This stands in huge contrast to productions such as the dreadful “Rings of Power”, the Disney Star Wars sequels, the Witcher or the Wheel of Time etc where creators try and impose their own world view on cultural/ racial issues and end up landing on their faces. Jackson specifically and deliberately avoided the “modern audience” bear trap. That is why it is a timeless masterpiece.

My all-time favourite trilogy. I could watch it over and over again and still be on edge when Frodo gets to Mount Doom!