Which agencies represent the most in-demand directors?

I gathered data on a thousand directors and their agencies to understand how much control a handful of companies really have.

A few weeks ago I looked at which Hollywood agencies represented the top 2,000 acting names.

This prompted a few readers to get in touch and ask if the same domination (i.e. four companies representing half the entire field) is present for directors.

To answer that, I gathered data on the top 1,000 directors and linked them to their current agencies. There is more detail on my methodology in the Notes section at the end of the article.

It’s lonely at the top

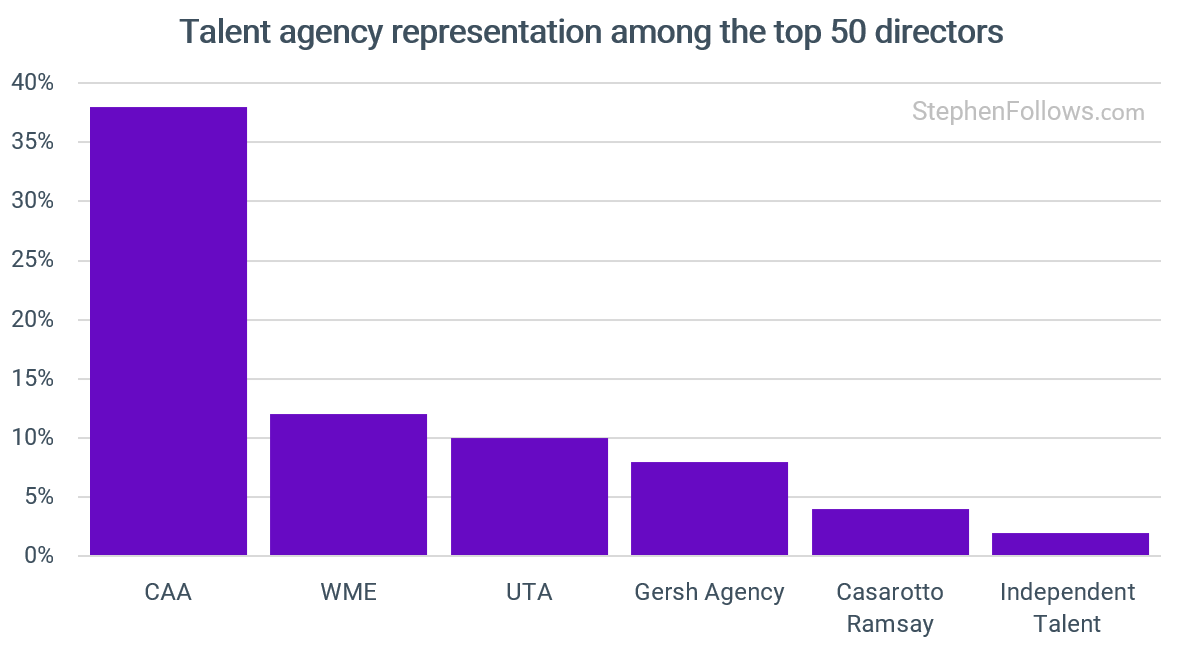

For actors, Creative Artists Agency (CAA) was at the top, with almost a quarter of top actors on their books. The effect is even more pronounced among the most elite directors, as CAA represents 19 of the top 50 directing names (38%).

Coming in behind are William Morris Endeavor (WME) at 12%, United Talent Agency (UTA) at 10%, and Gersh with 8%.

It won’t come as a shock to any industry-watchers that CAA is the top dog. CAA was founded in 1975 by five agents who left William Morris, and went on to restructure how Hollywood works. It introduced packaging, whereby the agency brings together a director, writer, and lead actor into a fully formed project and sells it to a studio.

This gave CAA enormous influence, allowing them to control not just talent deals but entire films. For directors, this means that CAA became a development engine, attaching financing, talent, and distribution from inside its own ecosystem. It remains the most powerful agency in the business, especially for top-tier directors.

Second placer WME, while also being a major player, has a slightly different profile to CAA. It was formed in 2009 when Endeavor acquired the legacy William Morris Agency, and since then has pursued a strategy of vertical integration. Through Endeavor, it owns major global properties like UFC, WWE, and IMG. The agency is structured more like a global entertainment company than a traditional rep firm.

When we widen the field, more come out to play

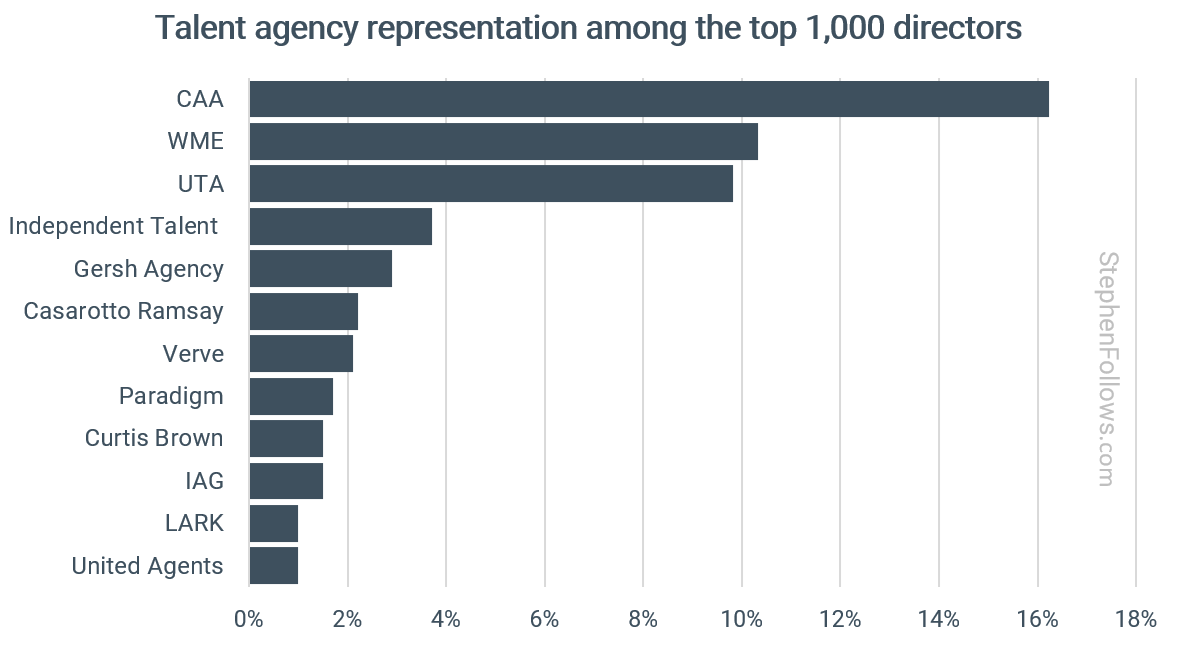

Zooming out from the top 50 to the top 1,000 gives us a fuller picture of how agencies operate across the spectrum of director visibility.

CAA is still top, but their share drops to 16.2%. The next two spots are taken up by WME (10.3%) and UTA (9.8%).

Gersh is smaller than the ‘Big Three’, but punches above its weight in director representation, especially in the independent film space. Known for its presence at Sundance, TIFF, and Berlinale, it represents many breakout voices and first-time filmmakers.

Independent Talent is the largest agency in the UK and a key player in British film and television. It represents a wide range of directors, from commercial studio names to public-service auteurs. Unlike US agencies, it doesn’t package aggressively or operate across media verticals. Instead, it offers deep ties to UK broadcasters, funders like BFI and Film4, and international co-production partners.

Casarotto Ramsay is probably the most unique of the agencies I’ve name-checked so far. It’s selective, independent, partner-owned, and focused solely on creative representation. It doesn’t represent actors, doesn’t take packaging fees, and rarely chases commercial scale. Instead, its directors are positioned for prestige work, long-term development deals, and international recognition.

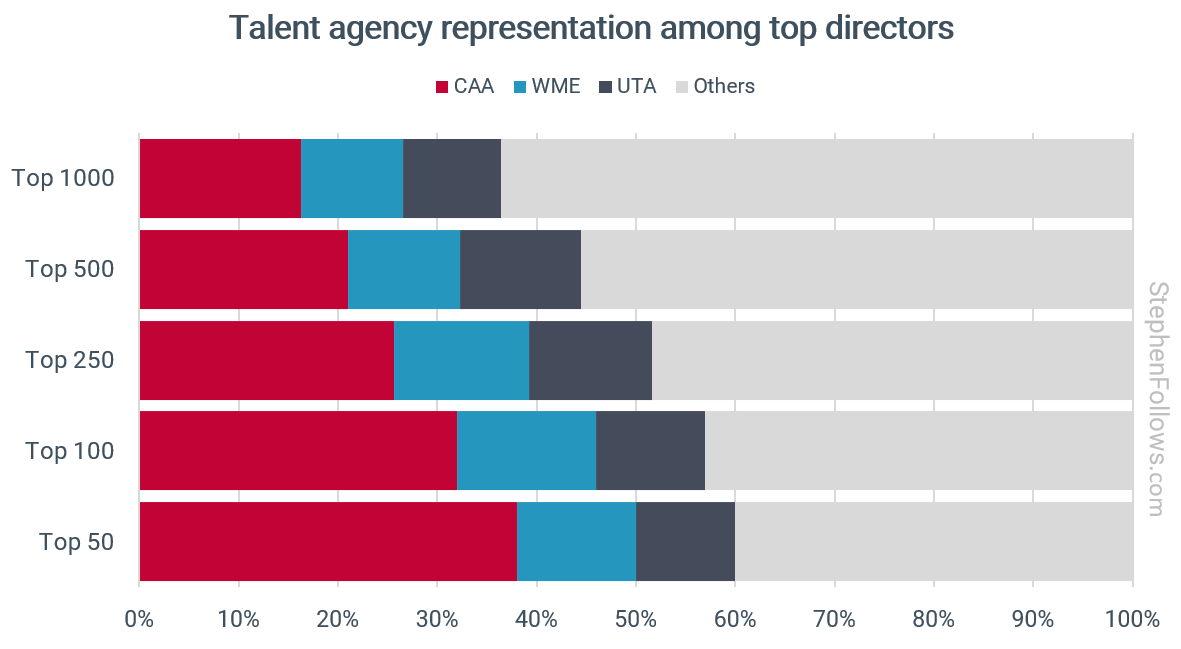

The ‘Big Three’ are top heavy

We’ve already seen how CAA dominates the very top tier but loses market share as we widen the pool of directors. This sets it apart from its neighbours, who have the opposite pattern.

WME and UTA may be less concentrated at the very top, but hold their ground more consistently as the dataset expands.

The result is that director representation looks more top-heavy than actor representation. The biggest agencies secure the most visible names, but as you move beyond the top tier the field opens up to a broader set of players.

How director-agent relationships differ from actors

Before we go, I wanted to quickly note that directors want slightly different things from their agent than actors do.

Representation for directors tends to be a slower, more strategic relationship. Instead of job-getting, the agent’s role is closer to career architecture. This difference shapes how agencies build their rosters and how power functions inside the system.

Where an actor might bounce between studio, streaming, or indie films year to year, directors often wait years between projects. In that time, it’s the agent who keeps momentum going, by positioning scripts, attaching cast, building financing, or shaping festival strategy.

Consequently, while actors often switch agencies after a single breakout role, directors rarely do.

Notes

The cohorts of actors I studied were based on IMDb’s STARmeter, which ranks actors by a combination of public interest signals, including page views and media coverage. It changes every week and I looked at it during the week commencing 25th August 2025. I’m sure if I re-ran this another time, the order of the people would shift around. That said, this is unlikely to change the overall picture in any meaningful way.

Actors move agents and agencies. This means both that the picture may change in the future, and also that just because a successful actor is currently with a certain agency it doesn’t mean that it was that agency that got them there.

Each director’s agency was taken from their IMDb Pro profile, focusing only on the first-listed agent. This is usually their main representative for film and television work. Some actors have multiple agents across different departments, territories or media. Some may also have managers, lawyers or publicists listed. These were excluded.

In just a few cases, no agent was listed. Percentages are calculated based only on those actors who actually had a talent agent named at the time I looked at it.

Although UTA acquired a controlling stake in Curtis Brown in 2022, I have kept Curtis Brown listed separately in this analysis. This reflects how directors themselves present their representation on IMDbPro, where Curtis Brown is typically listed as a distinct agency rather than as part of UTA. While the two agencies may collaborate internally, this approach preserves the way directors identify their primary representation.

It’s worth emphasising that this is not a measure of quality. An agency may have fewer clients because it is selective, or because it is smaller. An agent with many famous clients is not automatically more effective than one with a small, focused roster. Today’s research is tracking the representation distribution, not an endorsement of any one approach.

Finally, while directors within the same agency benefit from shared infrastructure and branding, they may have different personal agents, priorities or strategies. This analysis treats agency affiliation as a meaningful organisational link, but not as evidence of uniform treatment or outcomes.

Interesting that five UK based agencies are in the list of agencies repping the top 1000 directors, and two in the top 50 directors, I was surprised by this. I expected it would be all the US agencies but I guess it's that UK based directors are naturally making English speaking shows so there is a transfer of their high profile credits to US channels and cinemas.

Whereas European/Asian/other directors make shows and films that are less prominent in English speaking countries so they would be in less demand in the UK and US and so less visible at the agents of those countries.