Industry watchers (and regular readers) will know that there is an increasing concern in the film business about the declining cinema attendance among young people. Teenagers and young adults have always formed the biggest group of cinema attendees and yet we have seen a decline in many countries in the current decade.

Last week, I ran a symposium for senior industry figures in UK cinema, supported by Into Film. In attendance were representatives from the biggest cinema chains, distributors, public bodies, industry bodies and some big names from film production. The event was a private forum for executives to share their experiences, ideas and solutions with the aim of increasing cinema attendance among young people. (Note: We observed the Chatham House Rule, meaning that I can share what was said but not who said it. This proved vital in the discussion of the topic and for the freeflow of ideas).

To aid the debate, I worked with Liora Michlin to prepare two new reports on the topic:

A literature review of 47 existing studies into young audiences, summarising and collating the key findings.

A survey of 1,000 11-to-15-year-olds in the UK, looking at their attitudes and interactions with cinema-going.

The full papers are available to download at the links above but I thought I would pick out nine choice tidbits and three primers on the topic. We're going to address three questions:

What is happening to cinema attendance among young people?

Why does this matter?

What can be done to regain younger audiences?

What is happening to cinema attendance among young people?

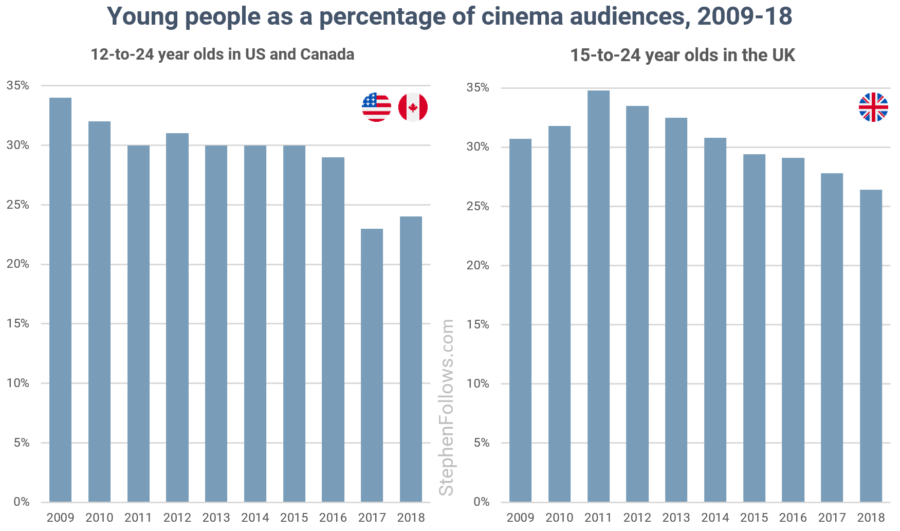

Ever fewer young people are visiting UK cinemas. Between 2011 and 2017, UK cinema admissions were close to static (a 0.6% decline) whereas admissions from 15- to 24-year-olds fell by 20.6%.

It's not just the UK. Many other countries have seen a decline, including major markets such as the US and Germany. The International Union of Cinemas (UNIC) reports that the average age of a cinema-goer in 2001 was 38.3 years old, whereas by 2016 it had risen to 42.6.

This trend is related to the cinema itself. There has been no comparable change in young people’s engagement with other major art forms.

The trend is best illustrated in the two charts below. The UK data comes from Film Monitor via the BFI and the US data is from the MPAA. (More on the data in the Notes section).

Why does this matter?

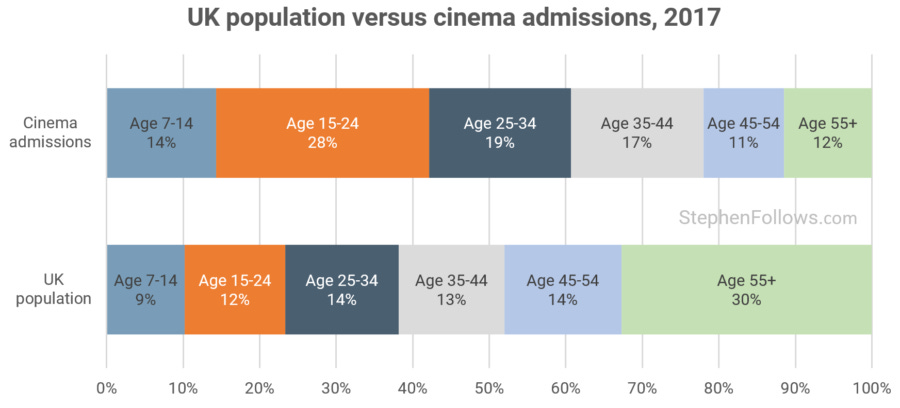

Young audiences are a key demographic for cinemas. 15- to 24-year-olds make up a larger proportion of cinema audiences than any other age group – in 2017 they made up 28% of admissions in the UK, despite being only 12% of the population. In addition, young people are especially over-represented during opening weekends and opening week, and once they engage with a film they tend to be very active in all aspects of it.

Due to the social nature of cinema-attendance among young people, a small decline could spiral. One of the common reasons young people cite for not going to the cinema is not having people to go with them. The network effect suggests that as fewer young people attend cinemas, their remaining pro-cinema peers will have even fewer people to go with, creating a vicious cycle further depressing demand.

Cinema-going habits are formed young and remain as we age. If the current generation of young people disengages with cinema-going in a big way then it is unlikely they will attend cinemas in the decades to come. This also extends to the appreciation of film as an art-form (assuming that these non-cinema attending young people are not replacing their cinema viewing with equally-reverent movie watching on other platforms).

Using BFI and ONS data we can see that young people hugely over-index for cinema admissions.

What can be done to regain younger audiences?

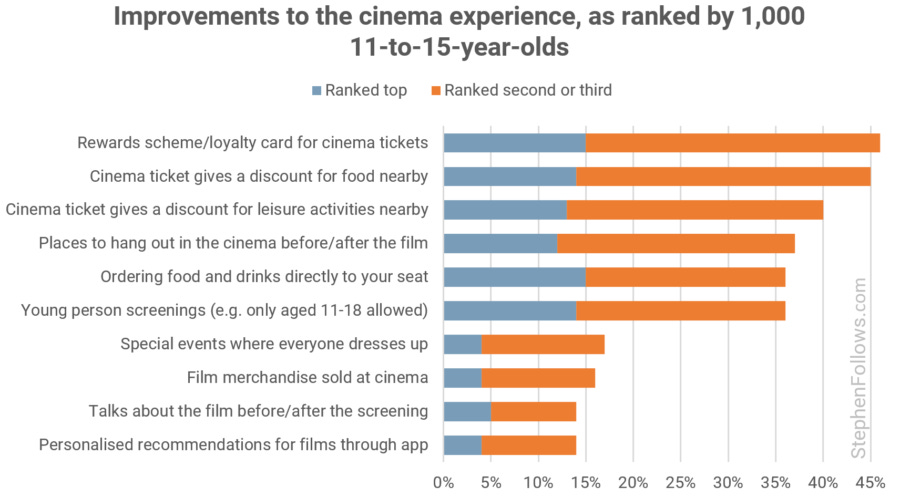

In our survey of 1,000 11-to-15-year-olds, we asked all sorts of questions around attendees and behaviours towards cinema attendance. I suggest you read the full report as I can only scratch the surface here. Nonetheless, I want to highlight three strong findings which suggest actions the industry can take to make cinema more attractive to young audiences.

Reduce the actual (or perceived) cost of a cinema trip. Spending money and socio-economic factors are very strong predictors of cinema attendance. In particular, a group we call 'potential cinema-goers' (i.e. those who like visiting the cinema, live near one but who don't go often) typically have less spending money and are from lower socio-economic backgrounds. This means that lower ticket prices are likely to increase cinema attendance among young people. The research also highlighted that it's not just the actual cost of the trip which matters but also the perception that cinema is expensive. Therefore, increasing the perceived value of a cinema visit could have a positive effect on attendance.

Tackle the struggles of organising a trip to the cinema. For regular cinema-attendees, friends/family having different film tastes is a strong block to going more often. Facilitating group outings for those held back by the film tastes of their friends is an opportunity to increase attendance, such as through film clubs or social mixers. Furthermore, a commonly cited barrier to cinema attendance is how hard it can be to organise a cinema trip and so anything cinemas can do to help with this is likely to have a strong positive effect.

Enhance the whole experience of a cinema trip, beyond just the movie being screened. The research shows that sociability is the key selling point of cinema for young people. This means that the whole experience before, during and after the screening is taken into account when assessing whether to visit. Cinema attendance is likely to be increased via things like sofas in the lobby, discounts on post-cinema activities (i.e. ten pin bowling), access to social eating facilities (whether on-site or nearby), etc.

A bonus note on programming

So far there has been no discussion of the films on offer. This is partly because younger audiences care much less about which movies are playing than older audiences (hence the state of modern Hollywood blockbusters) and partly because cinemas don't have a great deal of choice in what to show.

In theory, there are a large number of movies they can screen, as there are over 900 new movies released each year in the UK. However, in practice, the vast majority of tickets sold are for the biggest studio movies with massive marketing budgets and the most famous names. This means that if cinemas want to be able to pay their rent and staff, they have to be offering whatever major release opens each week.

However, our survey of young people did throw up one programming suggestion.

Boys go to the cinema more often than girls, but there is no difference in the proportion that have not been to the cinema at all in the past month. i.e. boys are more likely to be repeat cinema-goers. There was no difference in the perception of cinema as a most valued local facility, suggesting that the difference in levels of attendance between genders isn’t due to attitudes towards the cinema-going experience. Girls especially felt that the barrier to going more often is that cinemas were not showing films they wanted to see.

This suggests that more films targeted towards young women will increase cinema admissions among that group.

Notes

The literature review and new research together run over 62 pages and so I have heavily summarised the work for this article. If I have made a claim or quoted a statistic in this article which you would like to know more about, please take a look at the reports for the source, details, context and caveats. This blog is read by people in many different areas of film and some just want headlines. If you would like to go deeper, I highly recommend you refer to the reports rather than the article, just for the sake of being complete.

The data showing the percentage of young people in cinema audiences across the UK and Domestic markets are measuring subtly different things. The UK data come from the Film Monitor survey via the BFI Yearbook. It is gathered via exit polls of audiences seeing a selection of top films each year. The US and Canadian data cames via MPAA annual reports, and covers "tickets sold".

I don't wish to imply that this is an uncontroversial or inevitable decline. One of the views expressed by a knowledgeable executive in the exhibition sector at the event was that there isn't really a problem in the UK. They pointed out that the decline is from a high base (i.e. in 2011, The Inbetweeners was a huge success with young audiences) and that young audiences are returning to the cinema at the level of the early 2000s. I would say that their views are in the minority among fellow film professionals but they are certainly not alone or without merit. It could well be that this is a minor cyclical blip which will naturally rebound in the fullness of time.

It's also true that there is nothing the film industry likes more than a declaration of doom and gloom - the UK industry especially! The history of the film business is that of crying "Agh! The good times are over", whether it be the introduction of television, pre-recorded videos, piracy, streaming, sequels or people enjoying superhero movies.

I'm extremely grateful to Into Film for their tireless support of the research and of the event. None of it would have been possible without their encouragement, work, resources and financial backing. Not only that, but this symposium took place during their month-long annual festival in which they hold screenings and events for over half a million school children across the UK. Chatting to Into Film staff on the day, I learned that our symposium was taking place at the same moment as almost 400 other events throughout the UK. Yikes!

I'm also very grateful to my co-author Liora Michlin, without whom the research and event would not have taken place.

Epilogue

It's impossible to know what the future holds for film and for cinema-going. There's no doubt that the world is changing in so many ways. The opportunities and pressures on young people today are so different from those of the past century that it seems extremely unlikely that cinema attendance will remain completely unchanged. However, despite the massive shifts we've seen in technology, social interactions and societal norms, young people will always need fun ways to be social in the real world.

One possible outcome is that the current trends continue and we see further fragmentation of the cinema into two ever-more-different experiences:

"Spectacle cinema" - Big blockbuster films get bigger, dominate more of the space in multiplexes and cinemas focus on brighter, louder shared experiences designed to provide visual and audible awe. We've seen how successful this can be for recent movies in the Marvel and Star Wars franchises.

"Premium cinema" - Plusher cinemas offer arthouse fare and unique experiences. Patrons pay a higher ticket price than those in the 'spectacle cinemas' and in return receive a premium experience, watch less spectacle-driven programming, with live elements. The Everyman cinema chain has profited from this approach in the UK and we can see examples of the programming from Secret Cinema and NT Live theatre performances.

The former is likely to skew younger, due to the types of the movies on offer and the social aspect of simultaneous shared experiences, both on- and offline. The latter would skew older, due to the increased cost, the mature setting and the movies on offer.

Who knows if this will come to pass. What is certain is that all aspects of the film industry flourish when they are connected to their audiences and what they want to pay for.