UK films with public funding hire more women

Today's article is an offshoot of two strands of research I've been working on over the past few years - gender in the film industry and UK films with public funding. I looked at the percentage of female writers, producers and directors within UK films, focusing on how the female representation changes between films supported by a public body and those that are not.

In summary...

20% of UK films shot 2009-13 received some form of public funding

Across all UK films 2009-13, women accounted for 14% of directors, 27% of producers and 15% of writers

On publicly-backed films, women account for 20% of directors, 32% of producers and 24% of writers

The BFI fund a disproportionately large number of dramas, biopics and period dramas

The BFI fund a disproportionately small number of horror, documentary and fantasy films

45% of period dramas made in the UK received some kind of UK-based public funding

Who are the public funding bodies?

One in every five features films shot in the UK receives some sort of public funding, underlying the significance of public funders in the UK industry. In 2013, public funding bodies spent £157 million on UK film – through funding, training and support. (This is in addition to the £206 million tax breaks given to UK films by the HMRC).

The major funders are the British Film Institute (BFI), the BBC and regional screen agencies that look after geographic areas of the UK. In all, I tracked 37 public funding bodies (details here). I used IMDb users and Metascore as proxies for quality as judged by film audiences and film critics, respectively. I was able to show that the vast majority of UK films with public funding received better scores than the UK average.

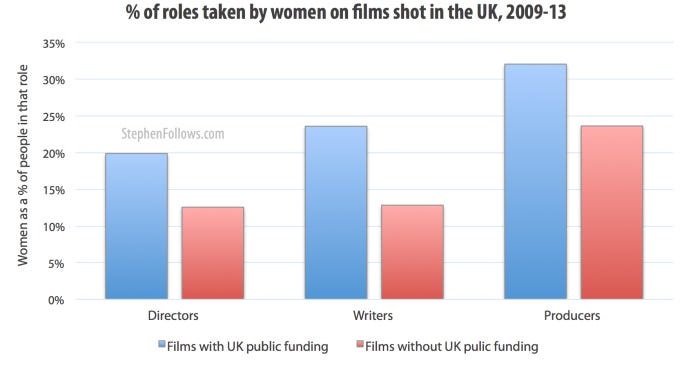

How well are women represented within UK films with public funding?

There's no getting around the numbers - women are massively underrepresented within UK film. Research I published last year showed that 14% of directors on UK films shot 2009-13 were women. Producers look a bit healthier at 27.2% and writers stand at 15.2% female. There is much debate as to why this is but I'm not going to address that in today's article. What interests me at this stage is measuring and quantifying the situation so we can have an open, healthy debate about the topic.

I combined my research into publicly-funded films and the gender split within the crew to see how the average percentage of women in key roles differs if a film receives public funding. And the results are quite clear - women are much better represented within the key roles of films backed by public funding.

19.9% of directors on UK films with public funding were women, compared to just 12.6% of directors on films not supported with public money. The trend continues with producers (32.1% versus 23.6%) and for writers (23.6% versus 12.8%).

Why is this?

Sadly, the numbers alone cannot reveal why this is happening – correlation is not causation. But it could be a combination of the following factors…

Female writers, producers and directors are more likely to make the kinds of films public funders wish to support. I've previously published research on the genres of the films publicly supported – i.e. a whole lot of dramas, period dramas and biopics and very few horror and action films. In the past I have also shown how the kinds of films women tend to write, produce and direct differ from men. Normally I would split out the data to test this theory but the number of films to study is so small in some cases that the margin of error would be quite high.

The public funding bodies are seeking out female creatives. Whether explicitly via diversity quotas or implicitly via personal choice of the decision makers. The BFI has recently instituted diversity quotas on all of its production funding, which includes gender, although the films I studied predate this quota.

People hire differently when they feel they are being watched (or have to submit an application justifying their actions). The film industry is mostly a collection of freelancers on short-term contracts, making it hard to monitor hiring practices. However, when a filmmaker wishes to apply for public support they are aware that their choices will be judged by others, and in some cases they need to provide details of why they have chosen the people they have. Social scientists tell us that people are more likely to act virtuously when they believe we're being watched and so this is a possible factor.

The kinds of people who make films outside of public funding are less keen to hire women. I find this argument unpleasant as that category includes my work as a writer and producer. That said, it cannot be ruled out as a possible factor.

But these are just possible reasons; further research is needed before we can say with any certainty why this is happening.

Notes

Today’s data relates to feature films shot in the UK between 2009 and 2013 (shoot year, not release year). For more details of the methodology please read the appendix of my ‘Women in UK Film Crews’ research which can be found here stephenfollows.com/what-percentage-of-a-british-film-crew-is-female