WGA Writers Strike 2017: The numbers behind the demands

You may have heard rumblings in the press about a possible upcoming writers' strike in Hollywood, and a few readers have been in touch to ask about the debate.

In today's article, I will look at some of the key numbers that lie at the heart of the disagreement between the writers and the studios.

I am going to avoid taking sides in this piece as my aim is to provide useful data for the debate, rather than to argue for one view or another. If I've missed anything, or if you want to add your thoughts on the topic, please do so in comments at the bottom of the page. Topics like this can arouse strong feelings on both sides, so I would ask that we keep it like the capital of Andalusia (i.e civil).

Which bodies are involved in the possible writers' strike?

Short answer: The writers are represented by the Writers Guild of America (WGA) and the employers are represented by the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP).

Long answer: The WGA is not actually one union, but two - the Writers Guild of America, East (WGAE) and the Writers Guild of America, West (WGAW).

The first dedicated American screenwriters' union was established in 1921 as the Screen Writers Guild (SWG), although it wasn't until the 1930s that it started to perform the duties of a union, taking on such activities as collective bargaining and protecting its members. The union grew in power and scope, joining forces with the Authors' League of America (in 1933), then with the Radio Writers Guild (in 1942) and eventually also representing TV writers (from 1948).

In 1951, the union split into the two bodies we have today - the WGAE and WGAW. The WGAE represents TV, radio and film writers east of the Mississippi and the WGAW focuses on TV, radio and film writers in Hollywood and California.

The two WGA organisations work together on collective bargaining and in the disputed agreement are treated as one party (called 'the Guild'). Therefore, for today's article, I will be referring to them collectively as the WGA.

The Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) is made of up "over 350" movie and television producers, including studios, broadcast networks, certain cable networks and independent producers. They represent "the employers" on 80 collective bargaining agreements within the creative industries, including with the American Federation of Musicians, the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, the Directors Guild of America, the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, the Screen Actors Guild, the Teamsters and of course the Writers Guild of America (WGA).

Every three years the WGA and AMPTP negotiate a new agreement which covers how writers are treated and compensated. It's the renewal of this agreement which has sparked the talk of a possible writers' strike in 2017.

What does the WGA / AMPTP agreement cover?

Short answer: The agreement binds film and TV producers to pay writers above certain mandated minimum rates of pay, and also requires that writers receive a share of some future income earned by the show or movie.

Long answer: The agreement covers a whole host of issues relating to how writers are hired, fired, treated, compensated and credited. I am going to focus on the financial side of the topic in this article, but it's worth noting that these agreements also cover things like pension rights, health care, travel expenses, dispute resolution and more.

Writers receive payment for their work via two methods - fixed fees and performance-related payments.

The fixed fees are normally paid before or during the making of the production. Part of the WGA agreement relates to what are known as 'WGA Minimums'. These are the lowest amount of money that writers can be paid for each tranche of work, such as a draft or re-write.

The performance-related payments are linked to the financial performance of the production and can be split into two categories - contingent compensation and residuals. Contingent compensation is a share of the profits a movie or TV show makes, and are typically reserved for the biggest writers on the largest shows. The WGA does not demand such payments for all its members and doesn't get involved as to how much these should be. However, all WGA writers are entitled to residuals, which are a highly regulated share of the income the production collects.

The exact amount of money due to a writer can vary wildly between productions, depending on how much work that writer did, where the production is screened, how the production performed financially, etc. Therefore, it's not possible to give a simple answer to 'How much are writers paid?' The WGA document summarising the current minimums is 45 pages long (you can read that here) and so including all that data would make this article interminably long. However, to give you a sense of how they work and how large they are, below are a few examples.

On films budgeted under $5 million, the WGA minimum for an original screenplay is $71,236 (i.e. 1.4% of the budget for a $5m movie). For films with a budget higher than $5 million, the same work would almost double the writer's income, at $133,739.

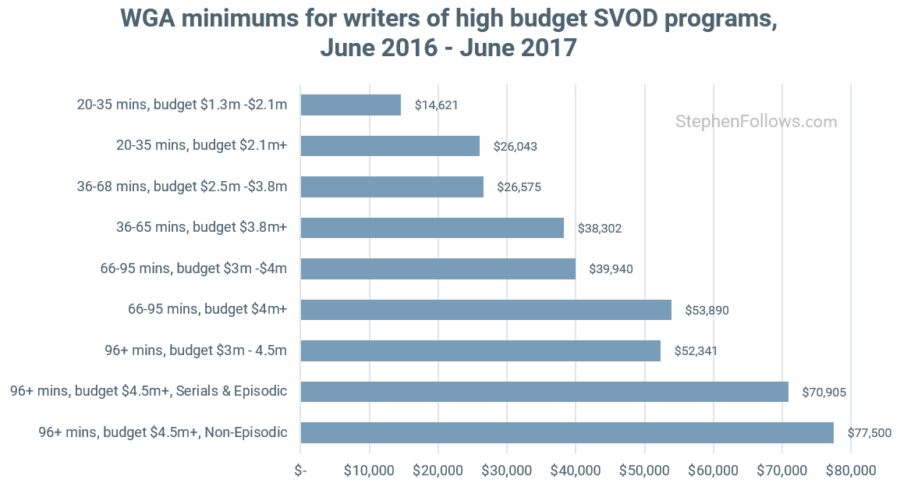

The WGA minimums for the writer of a "Low Budget" (i.e. sub $5m) feature film is similar to the minimum for the writer of an episode of a "High Budget" (i.e. over $4.5m) series on Netflix, lasting over 96 minutes - i.e $71,236 vs $70,905 respectively.

And finally, the WGA minimum for writing an episode of a network prime-time television show (i.e. on ABC, CBS, NBC or Fox) are similar to the High-End SVOD rates.

In addition to the money paid up front, writers are also entitled to residual payments. Feature film residuals are calculated as follows:

Theatrical (i.e. cinema) - No residuals are due for worldwide theatrical release, including in-flight, as this is regarded as being included in the original amount(s) paid and governed by the WGA Minimums as detailed above.

Free Television - 1.2% of distributor’s gross receipts for worldwide free television reuse.

Pay Television - 1.2% of distributor’s gross receipts for worldwide reuse.

Home Entertainment (i.e. DVD, Blu-Ray and VHS) - 1.5% of the first million dollars of the Company’s reportable gross (or “producer’s gross”) and then 1.8% thereafter. There is an additional 'DVD script fee' of $10,000 which is paid to writers. It's technically designed to cover the inclusion of the script on the DVD but is due to be paid whether the distribution actually includes it on the DVD or not.

Basic Cable - 1.2% of distributor’s gross receipts for worldwide reuse.

All of the above amounts are assuming that there is one writer for the project. However, if one writer receives a 'Story by' credit and the second writer receives a 'Screenplay by' credit, then the residuals will be split 25:75 in favour of the 'Screenplay by' writer.

In 2015, the WGAW collected $138,370,000 in residuals on behalf of feature film writers, 71% of which came from television screenings of the movies.

Television residuals are more complicated, due to the wide variety of shows and the need to deal with re-runs and syndication. While the money paid upfront is linked to the type of show and channel it is made for, residuals are often linked to the running time of the show. This means that while a writer of a one-hour prime-time network TV show may get paid a lot more up front than a writer of a one-hour basic cable show (i.e the minimums in these cases are $38,302 and $26,575), they will both receive a similar amount of money if their shows are re-broadcast.

The re-run residual is calculated using a 'Residual Base', which in the example above would be $24,558 for the network show and $26,575 for the basic cable show. (The reason that the network writer gets ever-so-slightly less is that it's based on run time and a "one hour" network show is actually shorter than a "one hour" basic cable show).

To cover television residuals, let's look at just one example - a show made for network prime-time.

First broadcast - The first time the show is broadcast there is no residual due, as it's assumed that the minimum paid upfront covers this use.

Re-runs on network prime time - 100% of the residual base.

Re-runs on network non-prime-time - It's a sliding scale, with the first re-run (i.e. broadcast #2) leading to a payment of 50% of the residual base and then declining on further broadcasts - broadcast 3 at 40%, broadcasts 4 to 6 at 25%, broadcasts 7 to 10 at 15%, broadcasts 11 & 12 at 10% and all other re-runs at 5% of the residual base.

Re-runs on network non-prime-time - Again, it's a sliding scale, with broadcast 2 leading to a payment of 40% of the residual base, broadcast 3 at 30%, broadcasts 4 to 6 at 25%, broadcasts 7 to 10 at 15%, broadcasts 11 & 12 at 10% and all other re-runs at 5% of the residual base.

Foreign income - An initial payment of 35% of residual base and then 1.2% of the foreign gross (after a certain threshold).

If you want to read an in-depth breakdown of how WGA residuals work, then check out this document.

Why are the WGA suggesting there may be a writers' strike?

Short answer: Profits among major studios are rising but the average television writing salary is falling. The WGA are seeking higher minimums and residuals to reverse this decline. Also, the WGA health insurance plan is close to going broke, so they want higher employer contributions to help stabilise it.

Long answer: Agreements between the WGA and AMPTP last three years, after which they are re-negotiating. In most cases, the two sides agree a slight increase to the minimums and residuals and a new agreement is signed. However, this time the WGA is digging its heels in and demanding that the next three-year agreement gives more than the employers are currently offering.

The current WGA agreement is valid between 2nd May 2014 and 1st May 2017, meaning that unless a new agreement is signed by the start of May, the WGA will call a strike of its members, thereby shutting down work on scripted movies and television shows until the two sides agree to a new deal. Reality television, re-runs and any show with scripts finished before the strike date will be unaffected.

The WGA says:

The entertainment industry has never been more profitable... In 2016 the six major media companies that dominate film and television, and employ almost all Guild writers (CBS, Comcast, Disney, Fox, Time Warner, and Viacom), reported almost $51 billion in operating profits. Those profits have doubled in the last decade and continue to grow... The entertainment business is thriving because of the content WGA members create... This content has fueled the global growth of the media companies and the meteoric rise of online video distribution. The companies which control this content have reaped the rewards many times over. Writers deserve a fair share of this unprecedented prosperity.

Issue #1: Television writers are receiving less money

Many current television shows have fewer episodes per season than even just a few years ago, and yet writers are still tied into exclusive deals. This means that the total amount they bring home has fallen, in some cases quite dramatically.

The WGA says:

During this ‘peak TV’ era, when more television is being produced than ever, and when everyone who works in television is finding a sellers’ market for their skills, why is the average TV writer seeing their income go down?

The percentage of writers who are working at the WGA minimums (i.e. the lowest amount the employers are allowed to pay them) has risen dramatically in the past three years.

The WGA says:

Writer-producers at all levels of experience have seen their compensation for a year of working on a series drop, at the median, between 8% and 26%. Even showrunners not on overall deals have seen their compensation drop 21%.

Issue #2: A hole in the WGA health plan

The WGA have a major problem in the shape of a $145 million projected deficit in their health plan, meaning that unless something changes it will be broke by 2021. Employer contributions towards this plan are lower than those made for directors (9.5% for writers and 10.5% for directors). In addition, due to the intricacies of the way the minimums are structured, the effective rate for most television writers is just 6%.

The chart below shows the trouble the WGA are predicting they will be in soon (figures for 2017 onward are estimates).

The WGA are asking employers to pay more into the plan, or in their words:

In this negotiation, we don’t seek a better health plan, only a solvent one.

Issue #3: Changes in development practices

There are complaints of exploitation by employers. The WGA agreements strictly forbid writers working for free, and detail minimums for each stage of work such as development, first draft, re-drafts, polishes, etc. However, in recent years there has been a rise in "one-step" deals, whereby a writer is paid just once for a single pass at a script. Traditionally, the vast majority of scripts are re-written a number of times before being ready to shoot, so the implication is that the one-step deal puts pressure on writers to do additional work for free, results in poorer work and means lower payments to writers. As the WGA puts it:

The worst offenses – pre-writes, free rewrites, sweepstakes pitching, screen writing rooms, and, one-step deals – are often exploitive at all income levels, but they are especially pernicious at lower levels of compensation. Many of these are enforcement issues, as free writing is already outlawed by the guild’s MBA. One-step deals are currently permitted by our contract. Curtailing these is a goal in the current negotiation.

At this stage, it's hard to tell what are the WGA's 'red lines' and what are just bargaining positions. It's a high stakes game and both sides wield pretty hefty weapons. A strike means a number of things:

The studios won't have any new content to sell. This will hurt their bottom line directly (via a loss in advertising income and fewer movies to release) and more indirectly (unpolished scripts will need to be made, resulting in poorer quality output).

The writers will have to go unpaid for the length of the strike.

A writers' strike will affect far more than just the writers. All of the cast, crew and support staff of cancelled or suspended television shows and movies will lose employment.

The studios may use it as cover to break other deals. During the most recent big writers' strike (2007-08), the major studios used the action as a cover to cancel a large number of 'first look' and development deals they had on the books but couldn't ordinarily get out of. Most such deals have a 'force majeure' clause covering unexpected major disruption, and this allowed the studios to cancel over 65 deals.

What's next?

It all depends on the talks currently taking place. The WGA do appear to be set on striking, but doing so would be painful and expensive for everyone, so both sides hope for an amicable agreement.

Notes

Data for today's article came from the WGAE, the WGAW, the AMPTP, the US Office of Labor Management Standards and Deadline. I have presented more data and quotes from the WGA side of the debate because they have placed far more in the public domain than AMPTP. I'm happy to update it if and when more is available.

Epilogue

For many, this is a very complicated topic. Certainly, I have found it a mission to read, understand and condense the many 1000s of pages of rules, agreements and public statements by both sides. Things like residuals and structural changes in studio development practices are not easy to follow, which means that the potential strike will be hard for most people to truly understand.

While for others, this is a very simple issue: either 'Writers are being abused by profit-hoarding, greedy studios' or 'Overpaid writers put entertainment jobs at stake just to get themselves more money'.

I have tried to be impartial in the crafting of this article. But you don't have to be, in the comments below!