When and how the film business went digital

Last week, I looked at six trends for how the film business is changing. It got a great response and I was heartened to see such interesting, lively debate about it. One of the topics raised by a few people was the move from analog to digital processes. I didn't include the move to digital as a trend because it's not one single thing, with each corner of the industry transitioning at a different pace.

So this week I thought I would take you through a quick tour of when and how various aspects of the film industry moved to digital technology. For some aspects, I have lots of data, while others are a little scant. If you have knowledge or data on anything I'm missing, please get in touch and I'll add it to the piece.

Digital cameras in Hollywood

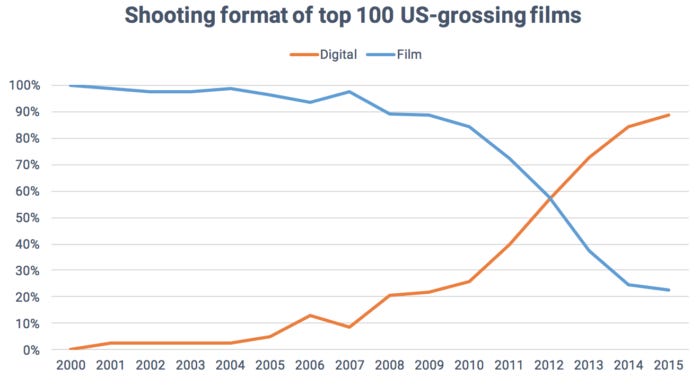

When most people talk about films 'going digital' they are referring to the move from shooting movies on celluloid film (typically 35mm stock) to digital cameras which capture footage as digital films on a hard drive. Hollywood started to capture films digitally in the 2000s but it wasn't until 2013 that digitally shot films were more common than celluloid productions among the top 100 grossing films.

Although we are moving to entirely new formats, many of the companies that dominated the film camera market back then are still major players. Arri was founded in 1917 and quickly became one of a handful of manufacturers of cameras and lenses used by Hollywood productions. Their first digital camera was the Arri D20 (introduced in 2005), followed by the D21 (in 2008) but it was their Alexa which became by far and away the most commonly-used camera among the largest Hollywood productions.

I have looked at this topic in more detail in the past: Film vs digital – What is Hollywood shooting on?

Digital cameras among independent shorts and features

By their very nature, independent shorts and features are harder to track than big budget Hollywood fare. They are often made by early filmmakers for little money and the vast majority don't get shown at festivals or to the public. This means that it's not possible to definitively say when the majority of independent filmmakers moved to digital. However, last year I was given access to the submission history of the Raindance Film Festival (2002-15) and so I have returned to that dataset to look at the formats used by filmmakers submitting to the festival.

As you can see below, it's not as simple as 'film or digital'. Many independent productions are extremely strapped for cash and so opt for the cheaper option of shooting on tape.

In the early 2000s, the most common tape formats were in standard definition (MiniDV and DigiBeta) but they were soon joined by high definition counterparts (such as HDV and HDCam). Digital overtook film for features in 2010 and a year later for shorts, but tape remained on top, right up to 2015. One thing to bear in mind is that the dates relate to the festival year, so a film submitting to the 2015 festival could have been shot in 2014, or even the tailend of 2013.

For more details, here is the full Raindance piece: Full costs and income of the Raindance Film Festival.

Theatrical release

Another area which benefited greatly from the shift to digital was exhibition. It was much quicker, cheaper and more secure to move a hard drive containing video files than huge cans of physical 35mm stock.

Distributors were keen to use the technology as soon as it was available but cinemas resisted as they were the ones who had to shell out for the new projectors. A compromise was reached whereby distributors pay an additional levy to cinemas when they screen a film digitally, called the Virtual Print Fee. In addition, the UK Film Council established the Digital Screen Network which helped fund the conversion to digital for 250 screens in smaller, regional and independent cinemas.

The two schemes ensured that UK cinemas screens were almost entirely digital by 2013. Pretty good, but still behind Norway and Luxembourg who were the first countries to go completely digital in 2011.

You can read more on this topic here: Digital film distribution in the UK.

Home Entertainment

Last week, the Entertainment Retailers Association announced that 2016 was the first year in which overall digital video spending (i.e. retail and rental) beat spending on physical formats.

It's actually quite hard to get exact figures because, unlike the physical marketplace, the digital marketplace is broad, diverse and often keeps numbers private. In the chart above, physical spend is as reported by The Official Charts Company and digital spend is a combination of estimates by IHS for many types of VOD (including EST, TV-VoD, web-based VoD and sVoD services).

Other aspects of the industry

Other pockets of the industry have moved to digital processes, but I couldn't find data on exactly when digital became the norm. These include:

Screenwriting. Perhaps the first areas to move to digital processes were those which needed very simple technology, such as screenwriting. Film scripts have a very strict layout and it was a nightmare meeting the specifications manually. However, templates in existing software packages (like Microsoft Word) and bespoke packages (like Final Draft) took the headache out of formatting. Final Draft was launched in 1991 and a rival, Scriptor, won an Academy Award for technical achievement in 1994.

Production Management. I couldn't find a date as to when industry-standard budgeting and scheduling software Movie Magic was launched, but I did find an old manual dating back to 2002.

Makeup, costume and continuity. As a film can take months to shoot, many on-set roles involve matching their artistic work to previously-shot scenes. In the 20th century, polaroid film was used whereas now digital photos are far more cost effective.

Editing. The digitisation of the editing process was a gradual one. For most of the 20th century, edits were made by hand on a 35mm copy of the rushes, with the editor physically splicing and sticking shots together. Once the edit was finished (i.e. "locked"), a Neg Cutter would cut the original film negative to match the agreed edits. The emergence of tape formats allowed editors to do the initial rough editing (known as "offline editing") on tape copies of the rushes rather than film, making the process cheaper, quicker and more user-friendly. The first tape-based editing suite was launched in 1971, but it wasn't until the 1980s that they become widely used. In the 1990s, computers had increased in power and speed to the point where the offline process could be moved into the digital environment. Very low-resolution digital copies of the rushes were edited on a computer and then the edits were sent to the neg cutter to produce the final 35mm negative. The first Hollywood studio movie edited digitally (on an Avid system) was Lost in Yonkers in 1993 and the 1996 Best Editing Oscar went to Walter Murch for the digitally-cut The English Patient. Filmmaker IQ have a couple of great free lessons if you want to learn more on this topic.

Post-production. Other aspects of post-production were also digitised (such as colour grading, audio and visual effects), leading to the situation we have now whereby the film stays entirely in a digital environment for its entire post-production period, via a Digital Intermediate (aka a "DI"). So even if a movie is shot on celluloid film, it will be completed digitally. As previously discussed, the vast majority of films are also screened digitally but the few which project on film (such as movies by Paul Thomas Anderson and Christopher Nolan) will be printed out to film once the DI is complete.

Notes

The data for today's piece came from the BFI, Raindance, IHS, Entertainment Retailers Association, The Official Charts Company and studies and databases I've built over the years. In some cases, charts add up to more than 100% due to the fact that some films use both digital and film formats.

Epilogue

This piece is a classic example of two aspects of this blog:

Firstly, it came from reader questions. If there's something you'd like me to look into about the film business then drop me a line.

Secondly, it will likely be improved, expanded (and corrected) by reader input, so please leave a comment below or send me a message directly if I've missed things off or got anything wrong.