Do Hollywood movies make a profit?

For the third part in my series on the financial side of the film industry, I am turning to profitability and asking "Do Hollywood movies make a profit?"

Hollywood has a negative reputation when it comes to transparency and financial openness. It feels as though each month brings yet another news story about a Hollywood flop losing millions or another lawsuit where people accuse studios of fiddling the figures to prevent having to pay out profit shares.

So let's take a detailed look at profitability among Hollywood movies. I will be working with three datasets, each providing a unique perspective on the matter...

The 'Insider' dataset. A collection of 279 films for which I have inside financial data, revealing the true costs and income for the life of the films. I have spoken about the sources of this data in a previous article, but for now just know what it's real-world reliable data which comes from people directly involved in the financial side of Hollywood movies.

The 'Nash' dataset. Nash Information Services, LLC (and their public-facing sister site The-Numbers.com) are the film industry's leading provider of 'Comp Reports' for movie business plans and they have kindly shared with me their internal projections of profit and loss for 2,819 movies. They use a variety of sources to provide figures on how much movies have recouped from each part of the film value chain. Producers, investors and organisations use this data to find successful movies comparable to theirs (known as "comps") to inform their production and investment decisions. (If you want Nash Information Services to create your Comp Report then click here).

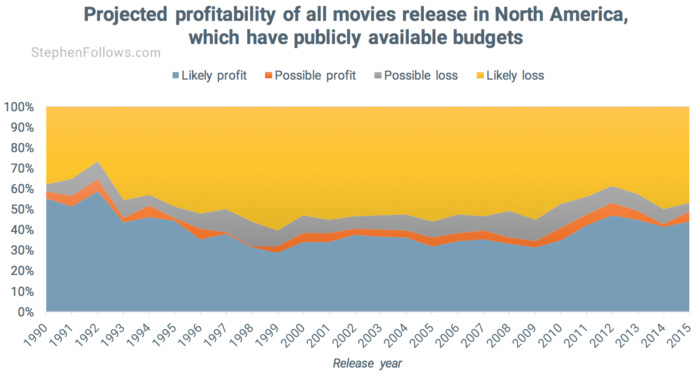

The 'Complete' dataset. This includes every film released in the US between 1990 and 2015 for which there is a budget figure online. I used the first two datasets to create rules of thumb on profitability and then applied those rules to this full dataset to get an idea of profitability across the whole industry.

What is profit?

I have frequently struggled to explain Hollywood economics to smart business types as they are often unwilling to be as flexible on certain terminology. For example, it can be completely legitimate for a number of stakeholders in the same movie to have different contractual definitions of profit. Three people who are each entitled to "1% of the profits" could each end up receiving vastly different sums, due to the particular type of "profit" they agreed to.

So let's define what we're discussing today. In a recent article, I went through at length all of the types of costs and income connected to making and releasing a Hollywood movie. We saw how a movie with a $150m budget will typically set the studio back around $417m when all costs for are accounted for. These include...

The original production budget

Marketing and advertising

The physical costs of getting the film in cinemas and on shelves

Contingent compensation for key talent

And other costs such as overhead, interests and financing costs

That same film will typically bring in $433m of revenue via...

The theatrical run (i.e. cinemas)

Home Entertainment (i.e. DVD and Blu-ray)

Television deals

Video on Demand (i.e. Netflix, iTunes, etc)

And other income streams such as hotels, airlines, merchandising and a cut of music sales.

So when we add up the money physically received from all income streams and subtract all costs, we're left with $14.8m "profit" for this typical $150m movie. And this is this definition we'll be using today when I talk of profit.

It's worth noting that studios charge their own movies a distribution fee (typically 30% of revenue received) within the costs calculation and so they will be generating far more turnover for the studio than just the $14.8m profit. However, I will assume that they earn this by applying their labour and resources in the act of distribution and won't include it in the final figure for how much the studio "made" or "lost" on each movie.

What percentage of Hollywood movies make a profit?

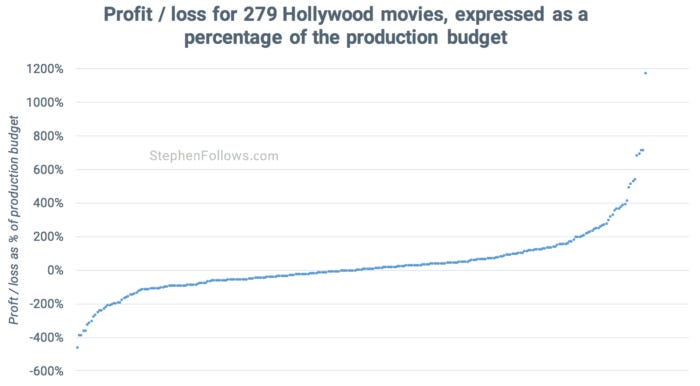

Using my 'Insider' dataset of 279 Hollywood movies I found that overall 51% made a profit and 49% made a loss. This pattern of 50:50 seems to be the common understanding of movie economics among the insiders I spoke to. When the final profit or loss is expressed as a percentage of the original production budget we can see how the majority of films make or lose a figure close to their original budget.

To provide a bit more context on the data above...

11% of the movies made a profit equivalent to more than twice their original budget

11% made a profit equal to between 100% and 200% of their original budget

28% made a profit equal to less than their budget

34% lost the equivalent of less than their budget

9% lost between 100% and 200% of their production budget

7% lost more than twice the value of their original budget

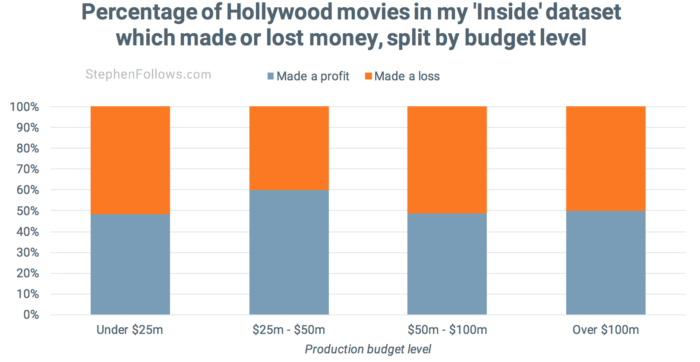

How does profitability change with budget level?

While it is helpful to know the percentage return, another important factor is the scale of the production. It would be twice as financially rewarding to be in the business of making $200m movies which make 5% profit than to be making $10m movies which return a 200% profit. So let's break the figures down by budget scale.

We can see that the 50:50 rule loosely applies to movies on every budget scale.

How important are the biggest winners and biggest losers?

Across all of those movies, the filmmakers and studios combined spent $31.0 billion and earned back $32.5 billion in revenue. This provided a profit of $1.5 billion, or 4.9% of the total amount spent. What's interesting is to look at where that money was made.

The top 6% of movies (i.e. those which made the most profit) provided 49% of all the money made by the profitable films. And similarly, the bottom 6% of movies (i.e. those which individually lost the largest amounts of money) accounted for 53% of the money lost by unprofitable films.

So, from the 'Insider' dataset we can already draw a few loose rules of thumb...

Across all these movies, half made money and half lost money.

Half of the money lost on unprofitable movies was lost on the worst performing 6% of movies.

Half of the money earned from profitable films came from the highest paying 6% of movies.

Can we estimate profitability for all Hollywood movies?

Now that we have some understanding of how films make a profit, I thought it would be fun to apply this learning to all movies released to make a good guess at overall movie industry profitability. There will always be some outliers (such as those movies which made unexpectedly high amounts on VOD or those which gross well but have very high costs to recoup) but overall these will be lost in the crowd of movies following the expected patterns.

To further refine our model, let's turn to the 'Nash' dataset of 2,819 movies for which the Nash team have financial performance data. All of these movies have been studied on the request of producers or investors who are investigating movies comparable to a project they are considering getting involved with. Therefore, we would expect there to be a higher-than-average number of profitable films (no one is going to pay for a report showing how a movie similar to theirs lost money!)

Across the Nash dataset, 64% were profitable and 36% lost money. What's surprising is that there are so many unprofitable films in this dataset as one would assume that the vast majority of movies were selected as the producer / investor believed they were positive case studies. Nonetheless, I guess it's better to be shown the financial reality on paper before any serious money has been committed rather than repeat an unprofitable route.

As the selection of films is not random, we cannot draw any lesson from the overall figures, but we can use the data to look for patterns which would allow us to infer profitability in Hollywood en masse. I decided to focus on the two figures which are most easily available for movies - the production budget and domestic theatrical box office (i.e. the total grossed in US and Canadian cinemas).

In a previous article, I explained the BFI's rule of thumb that they discovered when looking at the profitability of British films whereby if a film made twice its budget at the global box office then it was very likely to have made a profit. They tested this rule for their own films and with the help of independent private film financiers and they said it was robust.

Thanks to the Nash and Insider datasets, we can test this rule against the actual outcome. With just the production budget and global box office gross, the 'Twice Budget' rule correctly identifies whether a movie made a profit or a loss 72% of the time with Nash movies and 75% of the time within the Insider movies.

I have tried to find a more reliable multiple than just "budget times two" but unfortunately the intricacies of movie economics make this too hard to do with just the two figures to work from (i.e. budget and box office gross). Therefore, I tweaked the formula slightly to add an element of confidence to the result, rather than a binary "Profit" or "Loss" outcome, and then applied it to my dataset of all movies released in US cinemas between 1990 and 2015.

For the 4,526 movies I tracked, 37% were very likely to have made money, 4% were possibly in profit, 9% possibly made a loss and 50% almost certainly made a loss.

How can some movies gross many times their budget but still make a loss?

There are a handful of films which grossed a high multiple of their budget but still lost money. This may strike you as strange because one would assume that a movie which grossed, say, four times its budget at the box office would be guaranteed to make at least some money as profit. Not so, due to the convoluted way that money makes its way back to the filmmakers.

Note: In this section, I will refer to the people receiving the final profits of a movie as 'The Filmmakers' for ease. In truth, filmmakers will most likely have promised a share of these profits to investors, members of the cast and crew, etc. So whenever I say "The filmmakers received $x" read that as "The filmmakers / investors / people with profit points each received a share of $x".

Let me take you through the stages money passes on its journey from the movie-goers to the filmmakers. The proper name for this is a Recoupment Waterfall, although it occurs to me that 'Trickle Down Recoupment' may be more appropriate.

To see it in practice I included the figures for a fictional movie which cost £500k to make and grossed £1 million at the UK box office. Before you read on, have a guess about how much of the £1 million gross will be left for the filmmakers to recoup their £500k production cost.

Start with Cinema box office gross. The "box office gross" is the total amount of money collected by cinemas from movie audiences. In our fictional example, our film grossed £1,000,000 at the UK box office.

Minus sales taxes The first deduction is any relevant sales taxes which were added to the price of the cinema ticket. In the UK this means VAT (currently 20%), so the £1,000,000 box office gross actually includes £166,667 worth of VAT which goes to the tax man, leaving us with £833,333.

Minus the cinema's share. The exact percentage cinemas take from tickets is negotiated on a case-by-case basis between the movie's distributors and the cinema chains. Studios have much more clout than small independent distributors so can normally negotiate a better deal. It's also common for cinemas to agree to a lower percentage in the movie's first week of release compared with the rest of its run. A couple of years ago I ran a survey of 1,235 film professionals and asked about their experiences of distribution fees (you can read more about it here). The average figure charged by cinemas was 44%. To my mind this sounds a little low, as it is typically seen as around 50% for studios and can be as high as 70% for very small independent movies. For our fictional recoupment example I'm going to go with the wisdom of the crowd and so after the cinemas keep 44% of our remaining £833,333 we're left with £466,667.

Minus distributor's fee. The UK release of our movie has been handled by UK distributors, who now take off their cut. As with the cinema fee, the exact percentage will vary between movies, but my survey gave an average of 27% so that leaves us with £340,667.

Minus Prints and Advertising (P&A) costs. The costs of marketing (posters, trailer, advertising, etc) and of getting the movie physically in cinemas are all paid up front by the distributor. These can be considerable, with BFI data for 2012 showing that a film budgeted between £500k and £1 million will have average UK release costs of £190,000. This leaves us with £150,667.

Minus sales agent's fee. The UK distributor secured the rights to distribute our movie by doing a deal in Cannes with our exclusive global sales agent. The average sales agent fee in the survey was 19%, leaving £122,040.

Minus sales agents costs. Now we repay the cost the sales agent incurred in the selling of our rights in Cannes. This includes the promotional materials they made, a share of the costs of their booth in the market, travel costs etc. This can vary considerably (and is often a bone of contention for first time filmmakers who feel that too many costs are added) but I'd say that a reasonable estimation for our film would be £50,000. This means that we have £72,040 remaining.

Finally, we repay the filmmakers / investors. The movie cost £500,000 to make, so we have recouped just 14% of the money we spent or, to put it another way, so far we've made a loss of £427,960.

Wait! Don't conclude that it's all a racket, that you should stop reading and eschew film for more reliable professions like painting or pottery. Because there are some silver linings in this fictional example...

This was just the UK. Hopefully, our movie will reach other territories and will generate income there.

This was just theatrical. The movie will go on to earn money via Home Entertainment, Television, Video on Demand, etc.

The fixed costs have been repaid. Both the UK distributor and the global sales agent had fixed costs they needed to be repaid, which we have done in full. This means that a higher percentage of future income will actually reach the filmmakers.

When a small independent film is picked up for wide distribution by a Hollywood studio, the filmmakers could initially think that this means they're certain to see some money at the end. It's true that the studio may put their considerable marketing resources behind promoting the movie but it's also true that the film will need to recoup all those costs before money can trickle down to the filmmakers. In many such cases, the high P&A costs mean that filmmakers of the low-budget movie have seen nothing at the end of the day, despite their movie grossing highly in cinemas.

Notes

There are a few things to consider when thinking about the profitability of projections in today's research...

As we've seen, the movie business is led by extremes, where a handful of movies can either make or lose epic sums of money. This means that while overall the 50:50 rule seems to hold up, we can't say that each film has a "50% chance of making money". Success is the movie business may be opaque and tricky but it most certainly is not random.

It's possible for movies to fall well outside of the twice budget rule and yet buck the expected outcome. Movies can limp at the box office (due to poor marketing, unseasonably good weather or any number of unpredictable events) and then outperform on Home Ent, TV and VOD. Similarly, we can't know how much was spent on marketing so if a studio over-promotes a movie then its high box office gross could conceivably still be too slight to bring the movie into profit.

We're relying on publicly-available data for the budget and box office figures, which means the figures could be wrong and will certainly be incomplete. Last week and the week before, I compared the true budget for movies I have inside data for and the budget figures listed on Wikipedia. I found that movies costing over $100m typically cost 12.5% more than was reported and movies costing $30m-$100m typically costs 6.2% more.

Models need to take account of changing industry trends and conditions. The data I used to build today's assumption came from movies released in the past decade. Therefore, it's not possible to know how reliable this learning would be when applied to films from, say, the 1980s.

Epilogue

As always, feel free to contact me or leave a comment below if you have a question about anything I've covered today.

Next week I'm going to share some findings from a research project I conducted with Bruce Nash from The-Numbers on behalf of the American Film Market. We looked at films budgeted between $500k and $3m to discover what types of films "break out" and massively outperform compared to their peers.