This is an article I have wanted to research and write for a long, long time. I finally had a moment to sit down and crunch the numbers – I hope it helps in the understanding of Hollywood economics. It’s a lengthy one, so grab a cup of tea.

This is an article I have wanted to research and write for a long, long time. I finally had a moment to sit down and crunch the numbers – I hope it helps in the understanding of Hollywood economics. It’s a lengthy one, so grab a cup of tea.

Every six months or so, someone on my Facebook feed will share a list of “The Most Profitable Movies of All Time”. These lists normally use the budget of the movie and the amount of money it collected in cinemas worldwide to conclude how much “profit” the movies made. For example, “Paranormal Activity cost $15,000, grossed $193 million and so made a profit 1,286,566%“. Another popular fallacy is that when a movie with a $100 million budget crosses $100 million at the box office it is considered to have “recouped”.

While I understand why people fall for such over-simplifications, they have no real connection with how movies actually make money. Therefore, in an effort to demystify the film recoupment process I’m going to write a few articles looking at how movies make a profit. In the coming weeks, I’ll look at movies with smaller budgets but let’s start with the big ones – Hollywood blockbusters.

“We’re going to need a bigger boat”

Almost as long as there have been movies, Hollywood has relied on huge-scale productions to bring in the big bucks. Movies like Gone With The Wind, Ben-Hur and Cleopatra attracted large cinema audiences with a promise of cinematic spectacle. However, the first ‘blockbuster’ in the modern sense was Jaws (1975). The film broke box office records and created the modern summer blockbuster as we know it today. Its wide national release supported by blitz advertising created the first ‘event movie’ and became the template for later blockbusters including Star Wars (1977), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) and E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982).

Almost as long as there have been movies, Hollywood has relied on huge-scale productions to bring in the big bucks. Movies like Gone With The Wind, Ben-Hur and Cleopatra attracted large cinema audiences with a promise of cinematic spectacle. However, the first ‘blockbuster’ in the modern sense was Jaws (1975). The film broke box office records and created the modern summer blockbuster as we know it today. Its wide national release supported by blitz advertising created the first ‘event movie’ and became the template for later blockbusters including Star Wars (1977), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) and E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982).

In the past few decades, Hollywood studios have sought to perfect the model, and in so doing have massively increased the cost of making and promoting such movies. Modern blockbusters are often referred to as ‘tentpole movies’ as they represent the most important products in a studio’s release calendar. As the films have grown, so too have the spoils on offer. Last year, Jurassic World earned a whopping $1.67 billion in cinemas worldwide; quite a haul for a movie which cost $150 million to make. But after they recouped the original budget, how much of the remaining $1.52 billion turns into profit?

For today’s data, I am using a dataset of 29 Hollywood blockbusters, all of which cost over $100 million to make. The financial figures come from a few different sources within Hollywood studios, which I discuss in the Epilogue section at the end of this article. For now, just know that these figures are real-world, correct and relate to Hollywood movies released in the past ten years which cost over $100 million to make. (Note: The images and posters used in this article do not relate to the movies in my dataset – I’ve picked them because they’re nice images which seem to fit in well with the text).

What’s the average cost of making and selling a Hollywood blockbuster?

Before we can get to the numbers, here are some key phrases you’ll need to know to understand Hollywood economics…

Before we can get to the numbers, here are some key phrases you’ll need to know to understand Hollywood economics…

- Domestic – The release of the film in America and Canada, also known as “North America”.

- International – The release of the film in the rest of the world combined. In some cases, studios will only have the rights to release a movie domestically, with another company picking up the international rights (or vice versa). For example, Paramount have the rights to distribute The Adventures of Tintin domestically while Sony controls the international rights.

- Theatrical – Relating to the cinema release (i.e. in movie theatres).

- Home Entertainment (or “Home Video” or “Home Ent”) – The release of the film on DVD, Blu-Ray, previously VHS and online streaming services.

- Pay TV – Subscription television channels. In the UK this includes Sky Cinema and in the US cable networks such as HBO.

- Free TV – Free to air television, typically either public service broadcasting or ad supported. In the UK this includes the BBC and in the US ABC.

- Video on Demand (VOD) – Online streaming services (such as iTunes, Netflix and Amazon Prime).

- Pay Per View (PPV) – An old form of VOD which is still active in some places involving the viewer paying to watch an encrypted, scheduled transmission of the movie.

Ok, enough terminology – let’s start our journey into what Hollywood blockbusters cost and what they make back.

The first huge cost – The budget

The starting point for working out the final costs of releasing a movie is to look at how much it cost the studio to shoot the film (i.e. the film’s budget). In the industry, this is often called the ‘Negative Cost’ as it’s the cost of producing the very first version of the film (which used to be a film negative). This includes…

The starting point for working out the final costs of releasing a movie is to look at how much it cost the studio to shoot the film (i.e. the film’s budget). In the industry, this is often called the ‘Negative Cost’ as it’s the cost of producing the very first version of the film (which used to be a film negative). This includes…

- Development – Getting to a final script

- Pre-production – Building a team and planning the shoot

- Production – Shooting the movie

- Post-production – Editing, visual effects, sound design and music.

It will include most of the cast and crew’s wages but probably not the full amount paid to key personnel, such as the director or lead actors. These people may get additional money based on how well the film performs (known as “Contingent Compensation”) or a share of the money leftover once all the bills are paid (known as “Profit Participation”).

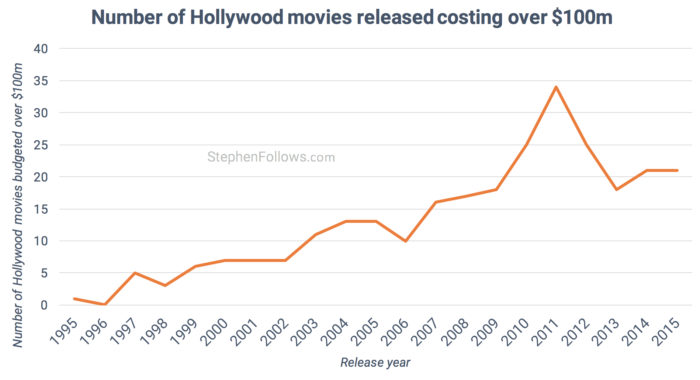

Budgets have been rising in recent decades, well above inflation. In the ten years between 1995 and 2004, there were 60 Hollywood movies released which cost over $100 million. In the following ten years (2005-14) this rose to 197.

The studios found themselves in an ever-increasing spiral whereby blockbusters were getting more expensive to make, meaning that they needed to spend more on marketing to offset the risk, which meant they needed to ensure their films are the biggest of the season, which inflated the budgets and the circle continues to turn.

Many feel that this cycle is not sustainable and a few years ago some industry watchers felt that a huge crash was imminent (Steven Spielberg and George Lucas both predicted an industry ‘implosion’). In the end, it seems that Hollywood has just reigned in spending with 2014 and 2015 having just 21 movies apiece, far below 2011’s high of 34.

Discovering the size of a film’s budget

Although technically a secret, a film’s total budget often leaks out and they are easy to find online (for example, Googling the phrase “Jurassic World budget” reveals that it reportedly cost $150 million to make). The information available online is normally a mix of true figures which have leaked and educated guesses by industry experts.

Although technically a secret, a film’s total budget often leaks out and they are easy to find online (for example, Googling the phrase “Jurassic World budget” reveals that it reportedly cost $150 million to make). The information available online is normally a mix of true figures which have leaked and educated guesses by industry experts.

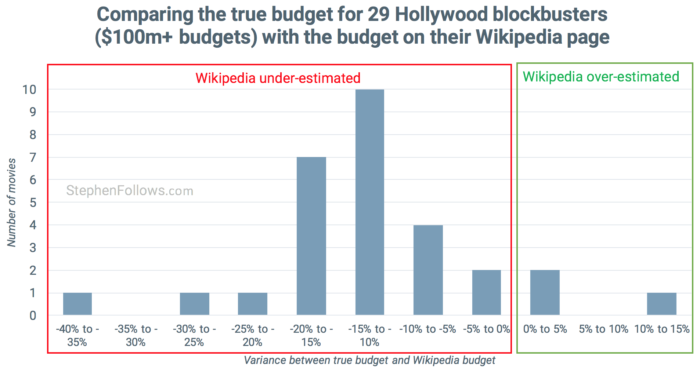

The studios often try to hide the true cost of a movie, in order to make themselves seem thriftier, smarter or more in control than they actually are. I performed a quick check for the 29 blockbusters I have inside data on compared with their budgets listed on Wikipedia. 90% of the films cost more than their Wikipedia budget with only three costing less than is declared on Wikipedia.

So the average $100m+ Hollywood blockbuster actually cost $19 million more than is stated on Wikipedia (i.e. 12.5% more).

For reference, the average budget for the blockbusters in my dataset was $150,567,000.

Other costs of making a movie

Releasing a Hollywood blockbuster involves far more than just creating 90 to 120 minutes of footage. Some of the other costs involved in making and releasing a film include…

Releasing a Hollywood blockbuster involves far more than just creating 90 to 120 minutes of footage. Some of the other costs involved in making and releasing a film include…

- Marketing – It could be argued that success in the business of Hollywood blockbusters is more dependent on the art of marketing than the art of filmmaking. This is the biggest category of costs for a movie, outside of the budget. Most Hollywood blockbusters only have one or two weeks when they are ‘The Big Movie’ in cinemas, so studios need to build and channel the awareness / excitement for a movie to ensure that everyone goes to see it during this period.

- Prints – The physical copies of the films which are given to cinemas. Historically, they were on 35mm celluloid film but today most countries use a hard drive with a specially encoded digital video file called a Digital Cinema Print (DCP). This hard drive has a huge copy of the film (10s or 100s of Gigabytes) and a tiny file which controls the permissions to the large video file. This means that hard drives can be shipped to cinemas in advance, without worry that the film will be viewed ahead of its official release. Complex permissions can be set, permitting screenings only at certain times or on certain digital projectors. Also, copies of the film in other formats will need to be created to give to third parties distributors and exhibitors, such as TV stations who broadcast the film.

- Residuals – Unions for the cast and crew have agreed deals with Hollywood studios which ensure that their members receive additional payments from the income the film generates.

- Financing costs – These can include costs involved with borrowing money to make the film (interests and brokerage fees) and currency conversions (for overseas shoots).

- Overhead – Studios charge their own productions an overhead fee which covers the time studio staff spend on the project, the costs of deals which apply to all films the studios make and the benefit a production is regarded as receiving from operating under the studio brand. It may seem strange to charge oneself money but these costs come off before “profit” is calculated, meaning that productions which pay an overhead have smaller official profits, meaning that the studio has smaller cheques to cut to people with profit participation deals. The old joke in Hollywood is that the studios charge overhead on interest and interest on overhead (and if you find that funny you really are down the rabbit hole of Hollywood economics!)

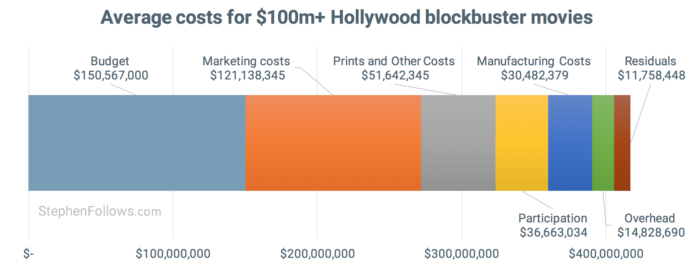

Looking at my dataset we can see the average costs breakdown below…

To give you a little more detail and context, below are some notes on each of the main cost areas…

Marketing costs

Is it often claimed that marketing a Hollywood movie can cost up to twice of the cost of the film’s budget, however from the numbers above we can see that this is untrue. Across my dataset of $100m+ movies, the average budget was $150.6 million and the average combined marketing spend was $121.1 million (i.e. 81% of the budget).

Is it often claimed that marketing a Hollywood movie can cost up to twice of the cost of the film’s budget, however from the numbers above we can see that this is untrue. Across my dataset of $100m+ movies, the average budget was $150.6 million and the average combined marketing spend was $121.1 million (i.e. 81% of the budget).

When expressed as a percentage of the total costs involved with making and selling a movie, marketing accounts for an average of 29% of costs. Across my dataset, the largest proportion of total costs going towards marketing was 40% and the lowest was 24%. It seems that the larger a movie’s budget, the smaller a percentage marketing makes of the total cost. While this may at first seem strange (we normally associate bigger movies with having bigger marketing budgets), consider that even films on the lower end of my dataset have budgets over $100 million and so their marketing efforts will be pulling no punches. In short, once you make a movie over $100 million you’re already using saturation marketing tactics so if you double a movie’s budget you can’t really double the marketing spend.

Physical delivery costs

The physical costs of creating and shipping prints to cinemas and of creating and shipping physical media to stores account for an average of $67.8 million. Judging the correct number of prints and units to manufacture is a key part of the planning done by the studios. If they order too few then cinemas and stores will have to turn away customers in the all-important first few weeks of release. If they over-order then their costs increase and they are left with annoyed cinema owners and large quantities of unsold units. Most units are sold on a ‘Sale or Return’ basis meaning that if studios over order then it’s their problem, not the stores.

The physical costs of creating and shipping prints to cinemas and of creating and shipping physical media to stores account for an average of $67.8 million. Judging the correct number of prints and units to manufacture is a key part of the planning done by the studios. If they order too few then cinemas and stores will have to turn away customers in the all-important first few weeks of release. If they over-order then their costs increase and they are left with annoyed cinema owners and large quantities of unsold units. Most units are sold on a ‘Sale or Return’ basis meaning that if studios over order then it’s their problem, not the stores.

In 2005, Dreamworks overestimated the number of Shrek 2 DVDs they would sell in the US by 5 million units. This caused the studio to missing their quarterly earnings target by 25% and their shares fell as a result.

Profit participation

The average $100m+ Hollywood blockbuster will spend $36.6 million on contingent compensation and profit participation. This typically goes to the key ‘creatives’ involved in making the film – namely the director, producer(s), writer(s) and key cast.

The average $100m+ Hollywood blockbuster will spend $36.6 million on contingent compensation and profit participation. This typically goes to the key ‘creatives’ involved in making the film – namely the director, producer(s), writer(s) and key cast.

Giving these people a share of the income is a good way for the studio to hedge against poor box office performance and it also defers the moment they have to pay up. Key talent often seek ‘participation points’ as a way of increasing their income and to share the spoils if a film performs much better than expected.

On the flipside, studios have got rather good at using creative accounting techniques to show that they made a loss on paper in order to get out of paying such fees. In 2010, a leaked profit participation report from the fifth Harry Potter film showed that two years after the film’s release, Warner Brothers was claiming that the picture had lost $167 million. Other movies hit with such claims are the three Lord of the Rings films (which combined grossed almost $3 billion in cinemas worldwide), My Big Fat Greek Wedding, Spider-Man, Return of the Jedi, Coming To America, JFK, Fahrenheit 9/11 and Forest Gump, to name but a few.

The movie in my dataset which gave the largest share of income to participants gave 18%. It’s worth noting that participation isn’t always dependent on there being profits. As people get wise to the studios’ game of creative accounting they are asking for more than just “a share of the profits”. The biggest names will demand ‘First Dollar Gross‘ deals, which give them a share of every dollar earned, calculated before costs are taken off. On average, the films which lost money in my dataset still paid out 5% of their income to participants (profitable films spent an average of 9% of their income on participants).

How do Hollywood blockbusters earn money?

With each “$100m+” Hollywood blockbuster costing an average of $417 million to make, there had better be some serious income to reach profitability. Fortunately, Hollywood is rather good at squeezing every penny out of a movie, ensuring that the target customer is given many chances to pay to see it. Before we look at the financial figures, let’s talk briefly about the journey a movie goes on to earn its money.

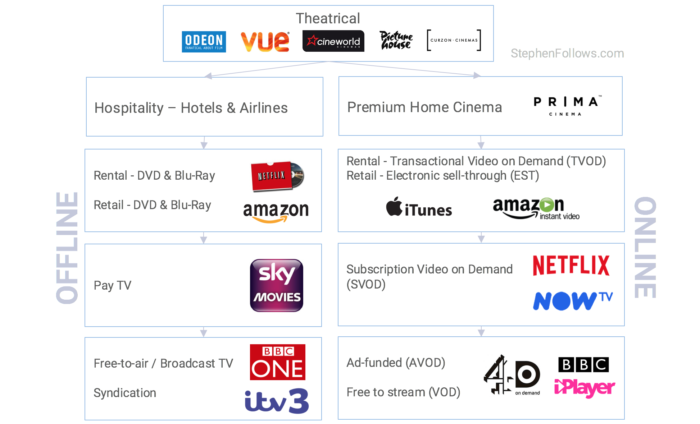

Movies may start in cinemas but they are far from the only place they earn money. Each stage at which a movie reaches a new type of platform (i.e. DVD, TV, etc) is called a “Release Window”. In recent years release windows have shifted around (including the elimination of a previously-profitable exclusive window called “Video Rental” – remember renting a VHS at Blockbusters, anyone?) but most Hollywood movies follow the same path.

Theatrical – Once you’ve gone to the time and expense of creating a blockbuster you’ll want to ensure you pick a release timetable which maximises possible returns and so studios carefully plan each movie’s release strategy. Studios announce their cinema release dates way in advance in order to claim coveted release spots, such as Warner Brothers who announced a release date for their superhero movie ‘Cyborg‘ 1,411 days ahead of time (it’s out in America on 3rd April 2020). I don’t have time to go into the cinema scheduling patterns of blockbusters here but I have written about release calendars in the past stephenfollows.com/hollywood-movie-release-pattern.

Theatrical – Once you’ve gone to the time and expense of creating a blockbuster you’ll want to ensure you pick a release timetable which maximises possible returns and so studios carefully plan each movie’s release strategy. Studios announce their cinema release dates way in advance in order to claim coveted release spots, such as Warner Brothers who announced a release date for their superhero movie ‘Cyborg‘ 1,411 days ahead of time (it’s out in America on 3rd April 2020). I don’t have time to go into the cinema scheduling patterns of blockbusters here but I have written about release calendars in the past stephenfollows.com/hollywood-movie-release-pattern.- Airlines and Hospitality – After the theatrical window, the movie will appear on airlines and premium Pay Per View (PPV) services such as in hotels. If you’re rather well-off then you can get access to this release window by forking out $35,000 for a Prima box and $500 per 24-hour movie rental. However, most of us mere mortals need to wait for the all-important third window – Home Entertainment.

- ‘Home Entertainment’ used to be split into a rental window and then a retail window, however currently they tend to appear on shelves at the same time. The length of time between the Theatrical and Home Entertainment windows is a hot topic in the industry. Studios want to reduce the time it takes for movies to move from cinemas to stores in order to capitalise on marketing efforts and to make sure the DVD is on sale when the movie is still fresh in the minds of consumers. However, cinemas saw what happened to the rental window (which was chipped away to nothing, leading to the destruction of the video rental store industry) and so they guard their exclusive period viciously. In 2015, the average release window between theatrical and Home Entertainment was 3 months and 23 days.

Video on Demand is the new hope which the industry is counting on to replace falling DVD income. Research I conducted last year, showed that the amount of time between the DVD and VOD release of the top 100 grossing movies has fallen considerably in recent years. In 2009, VOD consumers had to wait an average of 74 days after the DVD release but by 2014 this had fallen to just 14 days.

Video on Demand is the new hope which the industry is counting on to replace falling DVD income. Research I conducted last year, showed that the amount of time between the DVD and VOD release of the top 100 grossing movies has fallen considerably in recent years. In 2009, VOD consumers had to wait an average of 74 days after the DVD release but by 2014 this had fallen to just 14 days.- Television is the largest single source of income for British films, mostly thanks to the collapse of the DVD market in recent years (see more on this in my article from January this year stephenfollows.com/television-income-for-films). Hollywood studios agree details with broadcasters called ‘Overall Deals’ (also called ‘Output deals’) which cover all of their movies over a certain period for a fixed, pre-agreed fee. This gives the studios a reliable income and gives the broadcasters a steady supply of hot new content which their rivals can’t screen. At first, movies appear on premium channels (known as ‘Pay TV’), then they move their way to free-to-air channels and finally end up in Syndication on minor digital channels. Some premium Pay TV channels pay extra for the rights to screen a movie before it’s available on DVD or VOD and so the studios will be careful to craft a release pattern which maximises income.

- Merchandising – A final major source of income for Hollywood Blockbusters is ‘Consumer Products’ (or merchandising). This involves the studios licencing the rights to use aspects of the movie’s world (such as characters, items and places). An offshoot of this is Product Placement where the studios charge brands to feature their products in the movie. Sometimes this will appear as cash in the income of a movie but more often it’s a way of saving money within the film’s budget or getting access to requirement elements for free (such as Michael Bay’s deal with Ford who supply 100s of cars to destroy for each of his exposition-heavy crash-fests).

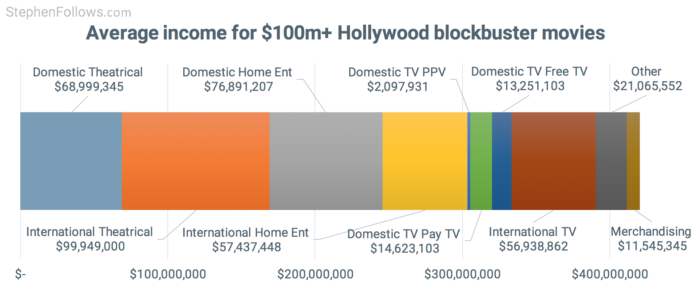

How much money do Hollywood blockbusters make?

Using my dataset of $100 million+ movies, I can share how much each of the sources of income contribute towards the bottom line.

Theatrical is the largest income driver for films, although not the most profitable. The average movie in my dataset grossed $129.9 million domestically (i.e. the US and Canada) and $243.3 million internationally (i.e./ everywhere else), leading to a total box office gross of $373.2 million. This is the figure you will hear reported on the news (i.e. “$100 million movie grosses $373 million – what a success!”). However, before the studios can see any of that money, two big costs needs to be deducted – sales taxes and the cinema’s share. Studios received an average of 53% of the box office gross domestically and 41% of the international gross. So that $373 million gross has already shrunk down to $169 million. When we remove the average theatrical marketing costs of $98 million we’re left with a margin of $70 million (i.e. 42% of the income). Other costs apply (see above) but already we can see how a $373 million gross can dwindle away fast.

Theatrical is the largest income driver for films, although not the most profitable. The average movie in my dataset grossed $129.9 million domestically (i.e. the US and Canada) and $243.3 million internationally (i.e./ everywhere else), leading to a total box office gross of $373.2 million. This is the figure you will hear reported on the news (i.e. “$100 million movie grosses $373 million – what a success!”). However, before the studios can see any of that money, two big costs needs to be deducted – sales taxes and the cinema’s share. Studios received an average of 53% of the box office gross domestically and 41% of the international gross. So that $373 million gross has already shrunk down to $169 million. When we remove the average theatrical marketing costs of $98 million we’re left with a margin of $70 million (i.e. 42% of the income). Other costs apply (see above) but already we can see how a $373 million gross can dwindle away fast.- Home Entertainment earns $100m+ Hollywood blockbusters an average of $134.3 million per movie. The margin is higher that the theatrical window, with an average Home Ent marketing spend of $21.9 million, leaving an 84% margin after marketing. Obviously, Home Ent has higher manufacturing costs, but these are an average of $30.5 million, making Home Ent a richer vein than theatrical. Now you can see why the studios are so worried by the fall in DVD sales!

- Television generates an average income of $86.9 million for $100 million+ movies and does so with little to no direct costs. Studios typically still charge a distribution fee to cover their time and lawyers but this is minute in comparison with the marketing and manufacturing costs of Theatrical and Home Ent. Within North America, the Pay TV window generates a slightly higher income than Free TV (average of $14.6m versus $13.3 million, respectively).

- Video on Demand performed very poorly for these blockbusters, with almost half of the films earning under 1% of their total income from VOD. That said, my dataset spans ten years and the studios were slow to build serious VOD operations. Looking just at the films released since 2011 reveals that 4.1% of their income came from VOD.

Merchandising generated an average of $11.5 million per movie in my dataset but this hides some big variations between titles. Only a third of movies earned over $1 million and almost two-thirds of the merchandising money generated from all 29 movies combined came from just two movies. It seems that the biggest Hollywood blockbusters can get up to half of their budget back in merchandising alone.

Merchandising generated an average of $11.5 million per movie in my dataset but this hides some big variations between titles. Only a third of movies earned over $1 million and almost two-thirds of the merchandising money generated from all 29 movies combined came from just two movies. It seems that the biggest Hollywood blockbusters can get up to half of their budget back in merchandising alone.- Airline and Music income can be viewed in one of two ways. It could be regarded as pretty inconsequential (totalling as it does just $2.7 million per movie) or it could be viewed as among the easiest deals with little to no costs associated.

Do Hollywood movies make money?

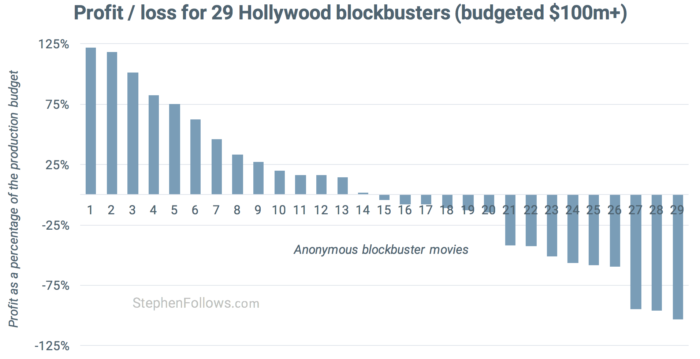

Of the 29 Hollywood blockbuster movies I studied, 14 generated a profit and 15 lost money. It’s impossible to know if these stats hold true for mega-movies in all of Hollywood but I suspect they do, due to the way my dataset was created (see Epilogue).

Note: The following discussion of profit uses this formula: all revenue received by the studios from a particular movie minus all costs they internally attribute to that production. This is an important distinction as a movie which has only officially broken even could still have provided a large amount of income for the studio via the charging of distribution fees, overhead and financing costs (see above for the section on Hollywood’s creative accounting).

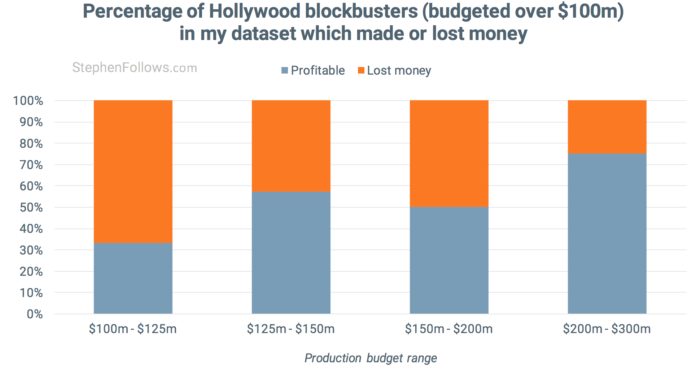

The smallest movies within my dataset (i.e. those budgeted between $100m and £125m) had the poorest record of profitability, with just a third making money. Conversely, three-quarters of the movies with the biggest budgets ($200m upward) generated a profit.

So rather than looking at individual films, let’s look at the big picture. Imagine you are an investor who put in 1% to all the films in my dataset in return for 1% of the profits. For ease, we’ll assume that you’re contributing towards all costs, you receive a share of all income and that the studios have taken pity on you and (for some unknown reason) decided to be honest with you about the numbers. Would you have made a smart investment?

Here are the combined financial figures for all 29 Hollywood blockbusters (budgeted over $100m)…

Here are the combined financial figures for all 29 Hollywood blockbusters (budgeted over $100m)…

- Total combined budgets: $4.37 billion

- Total combined costs (including budgets, marketing and all other costs): $11.52 billion

- Total combined income (from all revenue streams): $11.95 billion

- Profit across all movies: $428.9 million

- An average profit of $14.8 million per movie

That means for your 1% investment you would have spent $115.2 million, received $119.5 million back and made a profit of $4.3 million (i.e. a profit margin of just 3.7%). Considering that there is a delay between when you put the money in and when all revenue has been recouped, I think it’s certainly possible to imagine that you would lose this ‘profit’ to inflation.

If instead of playing with Hollywood you invested that same money in a standard high street bank paying 3% annually, over ten years your $115 million would become $156 million (an increase of 35%). And I am sure this is a fairly low return for that kind of cash.

Maybe instead of taking 1% of all the movies combined, you could try and spot the winners ahead of time. Let’s have a look at how the profit splits between the individual films…

So if you managed to put all of your money into ‘Movie 1’, then you would have a return of 122% (i.e. a $265.3 million return on an $119.5 million investment). The only problem is – how do you spot the hits? Hollywood currently employs the smartest, best informed and most profit-focused people in an effort to exclusively make profitable movies and yet half of their movies lose money. In fact, their combined best efforts only produce a 3.7% profit margin.

Correlations and curiosities

Before we leave the mad, mad economics of Hollywood blockbusters, let’s have a look at some interesting questions. (If you have a question not listed below, leave it in the comments at the bottom of the page and I’ll do my best to answer it from the data).

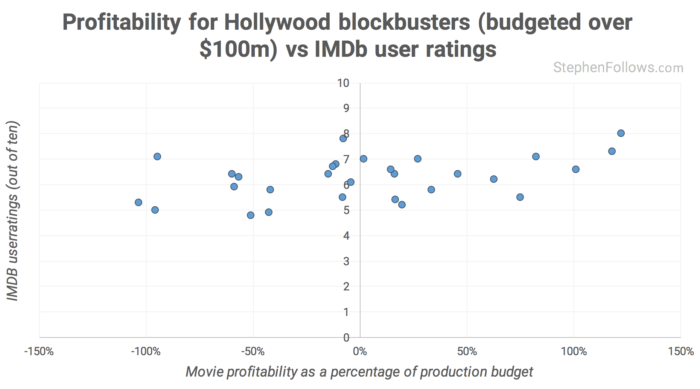

Q1: Are the films that make money better than those that lose money?

Yes, but only by a very small margin. The average Metacritic score (i.e. average of film critics out of 100) for profitable films was 55 and for unprofitable movies it was 49. Similarly, IMDb audiences rated the profitable films an average of 6.5 out of ten and the loss-making films an average of 6.1.

So it doesn’t seem as though the Hollywood studios have any financial incentive to make their films better. Shame.

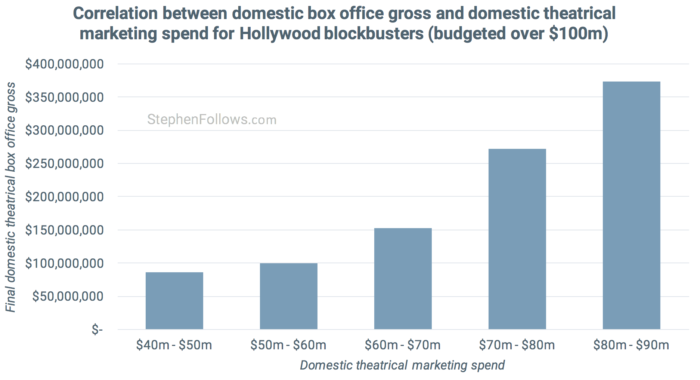

Q2: Does the amount they spend on marketing correlate with financial success?

In answering this question we have to be careful not to fall foul of the Statisticians’ Mantra that ‘Correlation is not causation‘. Studios don’t have to lock in their marketing commitments until they get close to the movie’s release date and so it could be that they choose to double down on the marketing when they know they have a film which is likely to perform well. Likewise, if they think they have a real turkey on their hands they could dial back the marketing spend so as not to throw good money after bad. From this data, we can’t tell why the correlation exists.

However, we can say that, yes, movies with the biggest marketing budgets do seem to gross the highest amounts at the box office.

Q3: How important is the international market, compared to North America?

Hollywood makes blockbusters for global consumption and in recent decades the share of the money the studios have received from countries outside the US and Canada has grown considerably. In theory, increased international business comes with increased charges as much of the international film business is conducted through third parties, which adds cost and complexity. Added to this, studios are less likely to make missteps on their home turf as they can be on-hand to scrutinise everything to a greater extent. So, does this ‘home advantage’ make the domestic market more lucrative?

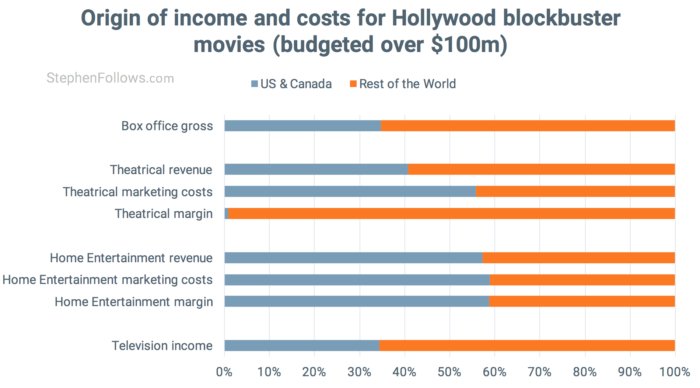

Well, it depends on which part of the process you look at. Below you can see the origin of revenue and costs for the blockbusters in my dataset.

As you can see, the majority of the money collected at the box office does indeed come from countries outside of the US and Canada. However, studios spend a higher proportion of their marketing money in North America. This could be for a number of reasons including the higher cost of advertising in America, the temptation to spend more in the country which studio execs actually live in and because the US is often the first place a movie is released and the media enjoy reporting on huge opening weekends (and decrying massive flops).

What’s fascinating is that once you deduct the release and marketing costs (known as the “Prints and Advertising” or “P&A”) almost all (i.e. 99.1%) of the theatrical margin left over comes from outside North America. This is the result of high fixed costs involved in releasing and marketing a movie in North America, the paper thin margins in the business (as we saw above, it’s under 4% across all these movies) and the more reliable nature of international returns. Together, they mean that only 12 of my 29 movies made money at the domestic box office, whereas 20 made money at the international box office. Alongside this, the losses at the domestic theatrical market were much worse than internationally. The poorest performing movie at the domestic theatrical market lost $49.3 million whereas the poorest performing film at the international theatrical market only lost $14.8 million.

So Hollywood looks to the international market with glee because…

So Hollywood looks to the international market with glee because…

- It’s cheaper to market movies internationally, with the average movie in my dataset costing $55 million to market in the US and Canada and $44 million for every other country the film was released in combined. For a sense of scale, IMDb lists release dates for Avatar in 69 countries, and I suspect the real number is slightly higher.

- The margin is more reliable and less prone to huge theatrical losses. As we saw above, the risk associated with releasing a big movie in North America is far greater than that associated with its international release.

- It has the most potential for growth in the near future as the North American market is saturated with cinemas and movies. For example, between 2009 and 2013, cinema admissions in China rose by 239%, whereas in the US over the same period they shrunk by 5%. You can read more about the enormous growth in the movie business in China here stephenfollows.com/film-business-in-china

Q4: Is there a rule of thumb for guessing which Hollywood blockbusters are in profit?

In the UK, the BFI developed a rule of thumb which stated that a movie was reasonably likely to be ‘profitable’ if it generated twice its budget at the global box office. They reached this conclusion by studying the full financial records of the movies they were involved with and also checking their hypothesis with independent professional film financiers. But their dataset would have included few (if any) films budgeted over $100 million, and so it’s interesting to see if it also applies to my dataset of Hollywood blockbusters.

In the UK, the BFI developed a rule of thumb which stated that a movie was reasonably likely to be ‘profitable’ if it generated twice its budget at the global box office. They reached this conclusion by studying the full financial records of the movies they were involved with and also checking their hypothesis with independent professional film financiers. But their dataset would have included few (if any) films budgeted over $100 million, and so it’s interesting to see if it also applies to my dataset of Hollywood blockbusters.

So the question is… If we only had two pieces of information – the global box office gross (as reported on Box Office Mojo) and the production budget (as reported on Wikipedia) – how accurately could we guess how many $100m+ movies made money?

Well, you’d be right 83% of the time. Using this rule, I was able to correctly identify all of the profit-making films and correctly identify ten as loss-making, however, this system incorrectly marked five loss-making movies as being profitable. (I also tested the theory against the true budget figures due to the fact that Wikipedia budgets are mostly inflated, as previously discussed, but this only improved accuracy to 86%). In short, the rule works in around four out of five cases. Not as reliable as one might have liked (and way below the accuracy the BFI found when the rule is applied to smaller films) but certainly interesting.

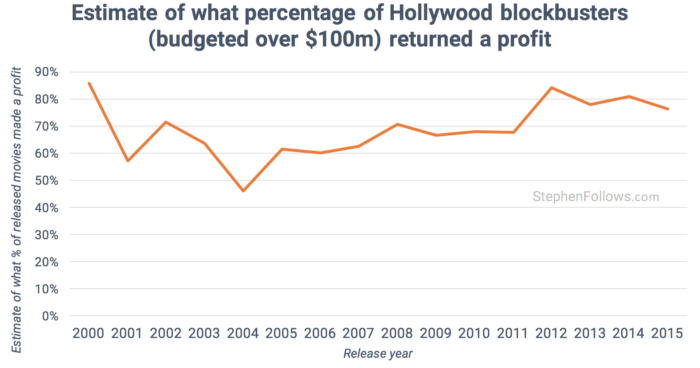

So far, I’ve been using a dataset of 29 movies in my investigations. But what happens if we apply this BFI rule to all $100m+ Hollywood blockbusters? I used just the published budget and box office gross to look at the 263 $100m+ movies released between 2000 and 2015.

This rule suggests that 70% of Hollywood blockbusters budgeted over $100m and released between 2000-15 were profitable. Since 2004, the percentage of movies in profit has been slowly increasing, from 46% in 2004 to 76% of those released in 2015. Most interestingly, it doesn’t seem that the huge number of releases in 2011 hurt profitability.

Epilogue

So there you have it – a rather long (sorry!) look at how movies make money and why when a $100 million movie makes $100 million in cinemas it’s not automatically in profit. I hope this has helped shed light on how Hollywood works and why the media’s traditional view of movie profitability is frustratingly wrong.

So there you have it – a rather long (sorry!) look at how movies make money and why when a $100 million movie makes $100 million in cinemas it’s not automatically in profit. I hope this has helped shed light on how Hollywood works and why the media’s traditional view of movie profitability is frustratingly wrong.

The biggest question some readers may have at this stage is – how did he get this data? Most of the raw data for today’s research is already publicly available via releases and leaks from major Hollywood studios, it’s just that I have spent the time to piece it together. I was also helped by a few well-placed friends in the industry who were able to fill in the blanks and confirm the veracity of some of the data points. I also used data from IMDb, Box Office Mojo, The Numbers, Metacritic and Wikipedia.

I am completely confident that the information in this article is a true representation of how these Hollywood blockbusters make money. The reason I am being a bit cagey about exactly where the data is from is partly to protect sources/ friends but also to avoid inviting lawsuits. The purpose of this site is educational and my sole intention is to help explain how our industry works. In the past, I have been contacted by lawyers for various companies, trying to prevent the sharing of key data points relating to their business. So far, I have managed to avoid lawsuits and also to avoid having to take any articles down, but if I were to offer the full figures as a download (or details of how to do the same piecing together I have) then I suspect I would get the wrong kind of attention.

So, if you want to know any more about these movies, please add your question in the comments below. I’ll do my best to answer them all, including going back to the dataset if needed.

Next week I will look at movies costing under $100 million.

Comments

Very informative and great info as always. It sucks there isn’t more transparency in Hollywood regarding spending habits, seeing how so many people attend film schools and festivals with hopes of entering into the industry not knowing what future really lies ahead of them, it’s also crazy to note how many films actually loose money, the government and film funds probably don’t want such info to made public as well.

Thank you, Stephen for some scintillating reading. When is someone offering you a book deal? Am I right that the last authoritative and widely discussed publication on film economics was David Puttnam’s Undeclared War (1997)? A lot has happened since, and there’s some big footsteps for you to fill.

I didn’t read all of this, but I will definitely be getting back to it, and it is a great task well done.

Thank you for all the work that went into this.

Thanks for sharing, this is fascinating stuff! 🙂

Great work Stephen – thank you. Would you expect the cost / compensation of producers, executive producers, associate producers etc. to be booked in the negative / budget or participation or overhead areas? And related to this can you demystify the roles, contributions and compensation for these various kinds of producers?

Thanks again for your superb analysis.

Wow! Very, very illuminating. Thank you. By the way, I’m very fond of your wife!

Very helpful. Re the query on books since 1997, our volumes Global Hollywood (2001) and Global Hollywood 2 (2005) are more recent than the 1997 one. They are also available in Chinese, Turkish, and Spanish

Thanks. Me too!

Stephen, please, please put all of this marvellous stuff in a book. It would blow people’s minds!!

Thank you for this amazing work! My question pertains to how you separate budget (a concept I usually hear referred to as “production budget”) from other costs such as marketing. To be more specific, I’ll use a movie example to state my question. Zack Snyder’s “300” is listed on IMDB as having a $65M budget. As an industry professional, I’ve been informed several times that the “production budget” of the film was $19M, and the rest of the listed budget went to P&A. However, viewing this example according to your article (disregarding the $100M+ theme and just focusing on the definition of “budget”), it seems that you would be suggesting that the $65M is the “production budget” of the movie (including dev, pre pro, prod, and post), but does not including marketing and other costs. Can you clarify here? Thanks again.

– Jan Lucanus

Hi Jan

I can’t speak directly to that production (and it’s certainly possible that different people use terms differently) but when people say ‘the budget’ or certainly ‘the production budget’ they mean the costs of development, pre-production, production and post-prodiction. Marketing and avertsing are not included, save maybe for the on-set photographer and a publicist who shows journalists around the set. This is particularly important for things like tax incentives, which almost never include publicity and distribution costs when calculating how big the budget is.

An interesting element of the debate on ‘What is a budget?’ is how you treat such tax incentives In the UK, films get around a fifth of the money they spend back within around six months of completion. So a film which cost £100m will get £20m back (in the real world it’s not so clean but humour me for this example). So, in this case, is the budget £100m and they just received ££20m of income or did the film really only cost £80m because that’s how much the studio had to sink into making it once it was complete? Both have a reasonable claim to be correct.

It’s true that a studio looking to make what we would call “a $150m movie” will need to set aside over $400m to do all the deals, distribution and marketing, but I don’t see that $400m as ‘the budget’. The budget is a real document created in pre-production which covers the cost of physically making the film.

Hope this helps

S

Great. Thanks so much.

An interesting way to look at the crazy economics of these large Studio pictures is to compare how they perform per $1m of budget. The 2007 Harry Potter film linked to has sold 3,256,969 DVDs in the UK, and sold 1,914,495 in the first month. So at a $316m budget it has sold 10,307 units per $1m overall, and 6,068 units in the first month. Now if this was a low budget UK film with a $1m budget, that level of DVD sales would be a disaster. The Gareth Evans film Monsters was made for around $500k, for that budget it has clocked up 241,591 DVD units overall and 88,582 units in the first month. So roughly 50x better on UK DVD that Harry…

I am just curious why online streaming services is listed twice, once under “Home Entertainment” and once under “VOD” – can you clarify the difference?

The Video on Demand (VOD) window is fairly new and so it doesn’t neatly fit into just one place.

Before internet streaming as we know it now, Pay Per View (PPV) was commonplace, in hotel rooms and on encrypted satellite and cable channels. This was split into the second window (“Hospitality” aka “Hotels and Airline”) and also in the “Television” window. As VOD has grown up, the newer services have become their own new window but the old way of accounting for the older services were retained.

So strictly, the idea of digital delivery of video on demand to the viewer appears within three windows!

Hope that helps (and doesn’t make it even more confusing!).

Thanks a lot Stephen, this is such a great job!

The film industry becomes so opaque when it comes to films budget and income… I assume opacity is necessary to keep investors on board in such a risky business but I’m pretty sure this is also a way for smart guys to still earn a lot on films that lose money. And that’s why someone like Ryan Kavanaugh lasted so long in the business.

Just two questions about the average costs graph:

1. What are the “manufacturing costs”? (just below the graph you define “physical delivery costs” which I understood is the definition for “prints and other costs” in the graph)

2. If “Participation” depend on the film income, shouldn’t it be something you deduct from receipts – like you do with the cinema’s share? Instead of being included in costs? (I know at the end that’s same result but not really the same way of seeing things)

The opacity occurs for a number of reasons but most are to do with hiding embarrassing or unattractive practices, because they can and because there is no benefit from being open.

In answer to your questions…

1. ‘Manufacturing costs’ relate to the Home Entertainment costs of making and shipping DVDs and Blu-Rays whereas ‘Prints’ relate to the costs of cinema prints.

2. Particpcation is a cost because it’s not always as simple as x% of cinema income. Sometimes the deal could be “If we reach $x at the box office then you’ll get an additional $x bonus”. These deals can be long and complex, and so they lose the direct connection with income that, say, taxes or the cinemas’ share have.

Wow Stephen. That was an amazing job – and very, very interesting – particularly your 1% investor’s return. Scary stuff.

I am amazed that in this digital era, “Print” costs are a massive 12% of total costs, or 34% of actually making the film. Do you have any thoughts or insights into why this is so extraordinarily high (to this outsider’s mind).

Thanks

Thanks.

Yes, I’m going to cover print costs in an article in the near future. I want to break down the costs and show how they differ between products. I’m going to focus on the financials for the next few articles and then come around to these other topics.

Thank you Steve for your informative article. The research that went into it must have been enormous as it covered so much of the movie business including distribution. I am currently involved with the production of the GHOST RIG and we are waiting for the new SAG rates, before we finish it. It is less than 10m but it is a great story that resembles PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN. I was really interested in the DVD sales figures and the overseas theatrical markets as the advertising would be less. Thank you for your info!!!

Michael L Edwards

3.7 percent profit… Jesus. Wonder how many points that number needs to drop for Speilberg and Lucas’s prediction to come true.

A question

You said that 5 movies were reported as making a profit but haven’t actually. Can you say the swing on that? I mean it’s like reported 5 miilion profit but actually or lost 2 or is it like 30 million profit and it lost 10?

Really great article.

Stephen, thank you for your informative detailed article. This is the sort of thing the internet would ideally be used for, instead of widespread trolling. Keep up the good work.

Adrian

Also how come financing costs aren’t on the graph?

Thanks in advance 🙂

Thank you for the information and the analysis you have performed. There is but one important correction/comment that I’d like to make. The ONLY people that know how much a movie costs in REAL $ terms are the producers. The real numbers are never released, nor should they. All these budgets posted on all of the sources you’ve mentioned are estimates based on rate cards, etc. Nobody in the industry pays those numbers. There are all sorts of deals employed to lower the REAL $ budget; there’s product placement, for example, used to minimise the REAL $ spend and improve the bottom line. There are “leaked” reports that some movies [e.g. The Smurfs] were profitable even before released because of product placement… don’t believe all that you read; that’s another industry secret.

At the end of the day, the important numbers and analyses come from what the windows revenue figures are and their relationships. This will help producers and distributors strategise what gets produced and how it’s marketed. As for profits… do magicians reveal their tricks? 🙂

Hey Adrian. Glad you found it useful. You’re right that most of the figures discussed publically are estimates, however the 29 movie dataset I used above are internal figures and the true figures. This allowed me to compare the true cost to that of the public figure (in this case from Wikipedia).

Hi Stephen, thanks for the excellent analysis. I’m curious about the “Other” category in the revenue chart. In your “pt2: $30m-$100m movies” article you split out VOD and Airlines and Music, but in this article I don’t see any revenue from those categories. Are those categories being rolled up into “Other”?

Also, you talk about the margin split between domestic and international, but I’m also curious about overall the gross margins among Theatrical, Home Ent, and Television. I have heard that on average the Theatrical makes close to 0% profit, Home Ent is 65%, and Television is 90% profit. Do you have any data to support or contradict these numbers?

Again, really insightful stuff you have here! Thanks

Yes, ‘Airline and Music ‘income is really small in comparison with the total.

And yes, sometimes theatrical income can be less than the cost of the release. The TV profit margin is much better than 90% as the cost are pretty much just contracts and delivery.

That said, splitting a profit margin between income streams is tricky as there are lots of non-release based costs you need to assign somewhere, such as the production budget.

Stephen;

James Spader was interviewed on Charlie Rose. He said without his appearances on “The Office”, he could not

have done “The Avenger to quote :”Now a days, to a great degree actors, writers and directors have migrated to television to be able to pay for the plays and the films that they may like to do.”

I believe your article explains why that is the reality but really are things that bad in the movie industry that

television is where actors, writers, and directors go to make money?

This was fantastic and certainly the most systematic treatment of any small class of pictures I have ever seen. Period.

Could we be greedy and ask for a similar arrangement for OTHER BUDGET RANGES?

OR GENRES, PERHAPS.

Truly, thanks so much.

Excellent Analysis – it’s extremely generous of you to make this sort of data publicly available Steven. You’re a wonderful contributor to the improvement of our industry. Many thanks.

I am quite new to the World of Film Finance, and I found your stats rather confusing, and I wondered what was your angle from posting them.

I watched at the Cinema recently with my partner and children the film:

Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle (2017) has made a 700% profit so far……

Jumanji’s BUDGET $90MM (estimated)

OPENING WKD $36MM (USA)

GROSS $321MM (USA) | and so far the film has grossed $772MM (Worldwide)

source Imdb

Your figures did not mention the tax breaks that investors get – on Hawaii http://variety.com/2018/artisans/production/hawaii-production-incentives-3-1202677431/ 20% and the other islands 25%.

Filming in the UK offers a 25% tax credit, and there are moves on the horizon to raise this to 40%. Within the EU the Canary Islands offer 40% tax break.

The investor profits more than you suggest.

Of course this is rather up to the film and cast, isn’t it?

However I thank you for your opinion, but is it peered reviewed?

Hi Lawrence. Thanks for getting in touch.

The numbers you quoted are gross, ie they don’t account for deductions. For example, in the UK there is a 20% VAT tax on all cinema tickets. Then there’s the amount the cinemas keep etc. This means that the box office gross is far greater than the amount which makes it back to the filmmakers or studio. See here for more info https://stephenfollows.com/how-a-cinemas-box-office-income-is-distributed/

Secondly, the UK tax credit (which is effectively 20%, not 25%) is often counted as a deduction on the production budget rather than as first income. It can be counted as either (there is much debate) but often the quoted budget figure has already taken this into account.

Finally, this article isn’t my opinion, it’s a collection of facts and real world data. You’re certainly right to say that each film is different but all work within the same system, often managed by the same people.

The picture I’ve painted is echoed by others in the know and in textbooks on the topic.

I hope that helps clarify things.

Good piece of information .

Take a bow Sir,for collecting these information.

Pls make some research on Bollywood Movie’s business.

So I just found this article. If a movie under performs at the theater box office but has strong streaming, home video sales, etc, would that potentially turn allow the studio to turn a profit even though the box office under performed?

Yes, certainly. Am some genres are more sceptical to the breakout hit than others. For example, The box office numbers for Christian movies in the US are probably just the tip of that particular iceberg.

Profit prediction models use data and rules of thumb to take these into account, as much as is possible. Certainly, aggregate profit figures over time or over an entire genre are likely to be correct, even with the odd breakout hit.

Hi Stephen, I just found this article, it’s fantastic. I especially like the test of the “double the production budget” rule of thumb. Have you tried to test a stricter rule-of-thumb like “triple the production budget”? I wonder how accurate this is in identifying profitable films. I struggle to imagine a movie tripling production costs at the global box office and still losing money…

Loved the article, I was just wondering though whether the rating of a movie was a factor in the profitability, do R movies perform better or worse than G movies. My mom told me that my niece and nephew watch movies like The Incredibles all the time but they probably have not seen Titanic yet. Does this sort of thing effect the overall profitability of movies or just some areas like merchandising.

Hi Joshua. Glad you enjoyed it. Yes, you’re absolutely right, the rating will affect its income. For a long time, the R rating was seen as the kiss of death but movies such as The Passion of the Christ, American Sniper and Deadpool have shown that it is possible to draw a sizeable crowd to an R rated movie.

Also, as you suggest, the big Studio tentpole movies need the broadest rating possible so that they’re not turning away possible paying customers. When the studios are figuring out which rating to shoot for they need to weigh up hard numbers (i.e. the largest possible customer base) with being able to deliver what audiences want (i.e. a good movie with enough thrills, scares and action, etc). A G-rated Deadpool would have disappointed many fans and no doubt resulted in lower attendance overall.

This is great. Thank you. Some quick thoughts (and possible answers to peculiarities):

1.) The focus on marketing domestically and not nationally could be explained by the fact that some international releases are delayed until they know it’s a success. For example, Japan. They are infamous for waiting many months later than all other international releases because Japanese audiences care quite a lot about if it was “internationally acclaimed.”

2.) And it could also be a correlation =/= causation thing as well. For example, I know China has a limitation on how many movies can be released per year. So the data may be skewed. It could be that the only films that get released there are safe bets, with established audiences and big budgets.

3.) The bigger the budget meaning bigger profit is to be expected. What would be interesting is to see if the percent ratio of ROI/profit was correlated in any way to the overall budget amount.

Thank you for everything you do and keep up the good work!

Fantastic and thorough analysis. Although I’m not in the filmmaking business myself, I run a digital book publishing company and I noticed there are some strong similarities there.

I was wondering if you’re aware of any resources similar to your tremendous website but targeted at the book publishing industry.

Thanks a lot. Keep up the awesome job 🙂

Great Article !

I am the publisher for ecran-total.fr media in france (French trade) we published a book with more than 60 film budgets I’d be very happy to discuss these withyou in the next festival . https://kiosque.ecran-total.fr/categorie-produit/livres/

keep in touch

Dear Stephen,

thank you very much for this excellent read – for the care and detail of your analysis.

I am particularly interested in the marketing part, as I am currently trying to produce a similar analysis to evaluate the ROI of marketing in various sectors, particularly music / publishing / film / video game and see where marketing dollars invested generate the most revenues.

Have you found any specific resources on this topic / online or offline / while you were researching this piece? Your numbers are quite precise – and the range of 24% to 40% of marketing costs in your data set is interesting to me.

Thank you for your time, and again thank you for writing this article.

What an incredibly detailed and informative article!

I’m curious, based on your dataset calculations, is the average “participation pool” percentage for S100m+ movies roughly 9%?

Also, using your data set (and a baseball analogy) I’d be interested to know what would be considered a “home run hit” a, “3rd base hit” and a “1st base hit” in regards to profit for S100m+ movies. i.e. the varying levels of success. Any thoughts?

Many thanks again for all this incredibly valuable information.

Best,

Shaun

Take a look at James Simon’s Ted talk. Such an algorithm has potential to take movies where they can be.

Assume a well done film project, what is the average production budget sweet spot for maximum profitability

A) You’re a rock star.

B) I’m your biggest Fan Girl (but you knew that).

C) If you ever want to co-author a book (or need a ghost writer), I’d love to be a candidate on your short list.

D) You’re a stud.

E) Thank you – from all of us – for collating, curating, studying, analyzing and sharing these numbers.

F) Thank you for running them backwards and forwards through all your spreadsheets, formulas and thought processes.

G) Thank you for culling through them, throwing out erroneous correlations and explaining aberrations and outliers as you share any relevant patterns, norms or themes you discovered or considered.

H) Thank you for being so intellectually curious that you proactively pursue these studies.

I) Thank you for being so industry generous that you benevolently share your analyses for our communal edification.

That is all I have to say for today.

For this post.

Hi, this is awesome. Just what I was looking for.

I have a question on the total cost and income. The components don’t seem to add up to your total.

Total cost in the components graph shows: $417 million, that means across 29 movies, it should be $12.1 billion

Total income in the graph shows $423 million, or $12.26 billion across 29 movies. This also translates to just 1% margin, not 3%. I’m trying to reconcile these numbers with say Lionsgate, which reports 5% margin over the past two years. Would love some clarification.

Reference to the text below:

———————————

Here are the combined financial figures for all 29 Hollywood blockbusters (budgeted over $100m)…

Total combined budgets: $4.37 billion

Total combined costs (including budgets, marketing and all other costs): $11.52 billion

Total combined income (from all revenue streams): $11.95 billion

Profit across all movies: $428.9 million

An average profit of $14.8 million per movie

That means for your 1% investment you would have spent $115.2 million, received $119.5 million back and made a profit of $4.3 million (i.e. a profit margin of just 3.7%). Considering that there is a delay between when you put the money in and when all revenue has been recouped, I think it’s certainly possible to imagine that you would lose this ‘profit’ to inflation.

Can you clarify how investors are paid back?

licensing fees, box office returns, before or after all the bills to create the movie are paid, before or after the director and actors are reimbursed? etc.

Hi Valerie. Certainly, check out this article from the archives https://stephenfollows.com/how-a-cinemas-box-office-income-is-distributed/

Hello, I’m a undergraduate in university break and found this article really fascinating. My question is what happens when a film doesn’t make a profit? Who is the first person or persons to lose their money?

Stephen,

Thank you for putting this together. Very much appreciate the information.

Ed Ondatje

Hello! A really interesting and informative peace of work. It is surprising how big a proportion of movie productions actually lose money. Since most of the production costs are pretty much “fixed” I guess the risk is carried by the production company (e.g. Universal Studios) up till almost 100%.. Therefore, it would obviously be very important to be able to predict the profitability before starting the actual production. Are there reliable studies in regard of this? As they say:”Predicting is difficult – especially predicting the future.” Although e.g. in the former Soviet Union it was sometimes more difficult to predict the past…. ;D Best regards and many thanks! Mr. Jari Matula, Finland

Hello Stephen

Am Kelvin from Kenya. Am writting a script and your figures are keeping me out. But wait, I hope you could link me to a “sponsor” so that i can film my Love story. How is that possible

Thank YOU. Thank you. THANK YOU!! I am just entering the industry and am in the process of making my Pitch Deck. I have felt so ill-equipped because I had no guidance on how to budget the film. Now, problem solved. Thank you for this article. It is saving me and my presentation.

Hey Stephen,

Great in-depth walkthrough of the industry.

I was wondering if you have any data on box office performance of different production with (rougly) the same marketing budget – maybe not only +$100M productions, but also in general?

Would be interesting to see if some marketing strategies could be link to better (or worse) box office performance!

Put money in the banks if more profit than making movies, someone has the same conclusion as you 20 years ago:

https://youtu.be/SU6dB0TWGWc?t=181

Thank you for this article. Very informative. My question is rather simple and stupid, but still. Reading this I understand that even Hollywood makes a loss most of the time. So we can say in general, making movies is not lucrative. In your opinion, how come it is such a big business? And why are we still making movies? I cannot imagine that (apart from heart-core arthouse lovers) even Hollywood producers are in it because they love movies so much. This romantic idea was probably real when Hollywood started, but today it is just another business. But reading the article, I don´t understand what makes all that stress worthwhile