Today I am answering a question from a reader who got in contact to say "I am working on a project right now and the investors are asking how long it will take to get their money back. Have you any idea what percentage of total lifetime revenues the average movie earns in Year 1, Year 2, etc?"

Analysing return in the film industry is always tricky, due to the fragmented and secretive nature of deals. However, there are a few places we can look to gain an insight into otherwise opaque areas.

In this case, we can study the returns of films backed by the British Film Institute (BFI). As a quasi-public body, the BFI is required to report the status of investments it has made each year in its full annual accounts. This means we can see how much the BFI put into a film and how much they earned back.

The average recoupment period for movies

I studied 328 feature films which received funding awards from the BFI (or its predecessor the UK Film Council). By piecing together the annual accounts we are able to get a picture of when money flowed back to the BFI.

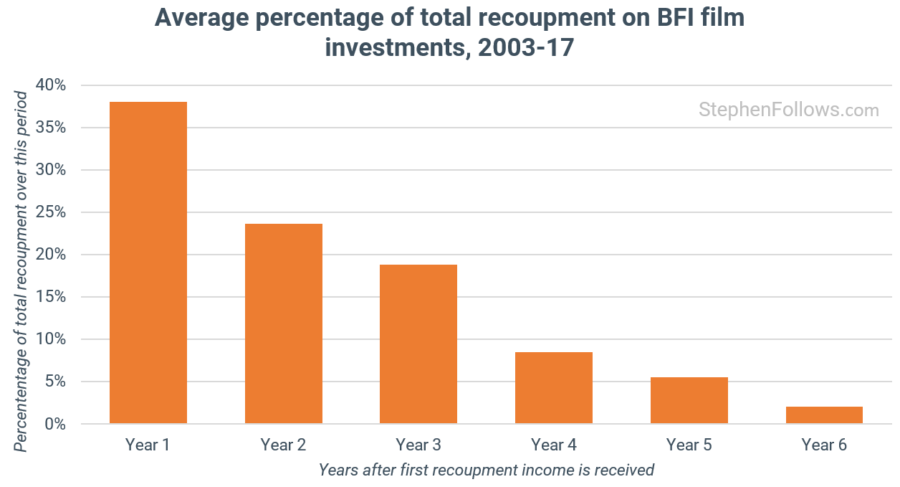

Over this fifteen-year period, just over a third of all the money came in during the first year of recoupment, with 89% being received within the first four years.

Examples of recoupment schedules

Each film will have a slightly different recoupment pattern. For example

Slow burns - An independent film can take time to get noticed and to gain worldwide income. For example, The King's Speech was unusual in that it took a couple of years to hit its peak as it was released internationally and eventually went on to win the Best Picture Oscar.

Up-front deals - A distribution deal could include a Minimum Guarantee (MG) which is deducted from future income. This can result in no income for a number of years while that MG is repaid. Most films never repay their MG but those that do will see a small trickle of income after that period. For example, 28 Days Later saw a large income in years 1 and 2, then nothing for a further five years, after which time money started coming in again.

Below are four examples from the BFI dataset. In each case, we're only seeing the BFI's share of income so sadly we cannot use them to calculate the total income each film received. That said, with the BFI earning over nine times its original investment on The King's Speech, we're able to conclude that the other investors must be pretty happy right now!

What this means for filmmakers and investors

In a 2004 Wired article entitled The Long Tail, Chris Anderson described a scenario whereby companies can make more money from selling a large number of low-volume products than by just stocking a few high-demand items. I have heard many new or inexperienced filmmakers refer to 'the long tail' as a key part of their recoupment plan. They envisage a world wherein even if their film does not make much in its first few years, it will go on to succeed by selling for a number of years.

As we have seen above, sadly this is extremely rare for film recoupment. In almost all cases, the money you generate in the first few years will represent the vast majority of lifetime income.

The exceptions to this rule are:

Films which spawn other products which live on, such as popular video games, live shows, albums etc.

The value generated from remakes, sequels, spin-offs etc.

If the topic or star gains greater fame or relevance long after the film's initial release (a case in point is any movie which featured pandemics right now!)

As you can imagine, these are fringe cases which rarely apply to indie films.

Further reading

Here are some past articles which will allow you to read deeper into the topics touched on today:

Data

The raw data for today's study came from the BFI's annual accounts. This means that it is historic data and refers to a particular type of movie. That said, the overall pattern does match the recoupment schedules I've seen for all manner of movies, from studio blockbusters down to micro-budget breakouts. Each film will have its own unique division of returns between years but overall the average pattern is likely to be as shown above.

In order to conduct today's study I built upon previous research I had conducted into BFI (and previously UK Film Council) funding. There are a number of notes and caveats mentioned in those projects which are worth considering. For brevity's sake, I will not repeat them here but they can be read at the BFI-related links above.

As this is annualised data, we do not get the kind of granular detail which would be more useful for cashflow purposes. For example, if a sales agent is paying money quarterly, is slow to make transactions and pays on the first day of a new financial year, then this will show up in the figure long after it was actually earned. However, I hope that the volume of films studied here minimises the effect of such fringe cases, and readers are reminded to take into account this kind of lag when discussing payments.

I updated this article soon after publication as I discovered that a small number of my figures for the year 2003 were wrong. I have now fixed them.

Epilogue

The BFI data was not in the easiest format to read or analyse, which one can only assume is deliberate, given how easily other information is made available by them. Given that the BFI hold all the data, it would be fairly straightforward to link this returns data and present it as neatly as they present their funding awards.

I suspect that one factor which is depressing action on this front is that BFI films rarely pay back their full award. Put another way, the vast majority of BFI-backed films do not breakeven. When I previously studied BFI returns, I spoke to many members of BFI staff at all levels and the consensus was that this was a PR concern and something the BFI doesn't want to highlight. PR is not my area so I can't say to what extent this fear is justified, or if the potential fallout is worth frustrating industry research.

What I can say is that not only is the lack of profitability no black mark against the BFI, it could even be read as evidence that they're performing their role correctly. A few things to bear in mind:

They are not designed to be a profit centre. They spend government and National Lottery money to improve and strengthen the UK film industry. They are part arts body, part trade body and part force for social good (i.e. improving access, diversity, education and opportunity). Their missions are hard enough already without also adding "make money" on!

They are filmmaker-friendly. One route to larger returns would be to toughen up the deal terms for the money they provide. By demanding an exclusive and/or early recoupment position they would no doubt increase their chances of breakeven, but at the cost of making any other investment in the movies much harder. Another project the BFI have is their Locked Box scheme, which means that a significant share of profits is returned to the filmmakers to make future films, further reducing the BFI's income but increasing the advantage to filmmakers.

The kinds of films the BFI fund are not the most profitable type. Due to its arts and diversity remit, the BFI is carefully choosing which films to make. They disproportionately fund period dramas and rarely support horror - the complete inverse of an investment strategy chasing a return.

Most indie films lose money. Across the whole sector, only around a third of theatrically released movies turn a profit and for the lowest budget range, it's fewer than one in twenty-five.

So from my perspective, I would hope that the BFI further open up their data in a format researchers can easily use. The collation and re-formatting of this return data took many, many hours of work, just to recreate what the BFI already hold in a structured format.