It appears to me that the UK film industry is currently in a period of increased introspection. Even before the Brexit vote, I noticed a rise in the number of questions I received from industry professionals, both online and in person, about what's next for UK film. Popular topics include equality within the industry, the dramatic fall in micro-budget production and the response of the British Film Institute (BFI) on various issues.

And then in June, the decision by UK voters to leave the EU shocked the film industry. The vast majority of filmmakers didn't have a working knowledge of how the UK film industry connected with European bodies and institutions, and only learnt the advantages they had been receiving once the decision had been made to discontinue them. Scaremongering by some pro-Europeans and promises of a better future by some anti-Europeans brought the industry's existential questions into sharp focus and provided a sense of urgency.

Added to all this, the BFI is currently soliciting views from all corners of the film industry to help develop its next five-year strategy. The previous five-year plan (ironically called 'Film Forever') covered all BFI activity between 2012 to 2016, and gave them three priority areas:

As Film Forever comes to a close, the BFI is running live events and an online consultancy to listen to what the industry thinks should be its new priorities. If you haven't already, I strongly suggest you add your thoughts here: bfiforms.formstack.com/forms/bfi2022. It won't take long, and the final strategy will influence almost everything the BFI does over the next half-decade.

In this spirit of introspection amid uncertain futures, I wanted to share the results of a survey I ran of 73 industry professionals in which I asked what needs to change in the UK film industry. The study was initially meant to be just for me, as I had been asked by a publication for my thoughts on the future of UK film and I wanted to ensure I was including everything relevant. However, now that we're in this period of change, I thought it might be helpful to share what I found.

The Film Tax Credit is unsurprisingly popular

Many respondents expressed their appreciation for the current tax system which supports the UK film industry through the UK Tax Credit and the EIS / SEIS schemes.

Some suggested tweaks which included increasing the scope for allowable costs (development, professional services, etc) and to ensure that more of the profit is kept within the UK industry and not sent back to Hollywood corporations.

Opinions vary on the BFI

Which films are backed by public money seems to be a topic on which few can agree. One person complained that the BFI only backs “unchallenging and unimaginative work” while another feared that “the current trend for dark/disturbing or raunchy/sex-filled drama is portraying British society as 'depraved'… and as a result, I believe it makes us more vulnerable to terrorist attacks”. Let’s hope that ISIS agree with the former respondent that UK films are “unchallenging”.

In my experience, people's backing for the BFI largely depends on the number of times they themselves have been supported or rejected by the institution. Those in receipt of BFI funding feel that they are doing a great job while those rejected by the BFI are less supportive.

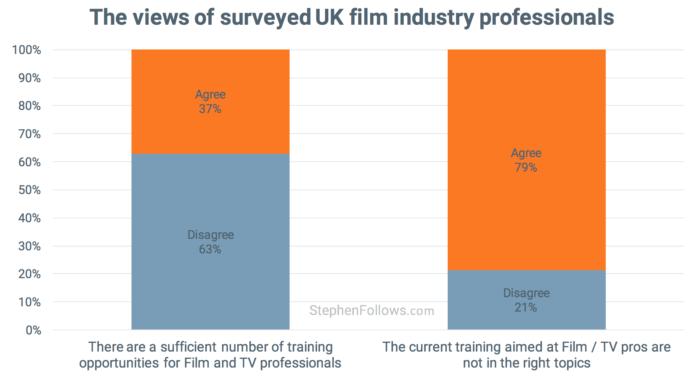

The industry needs more, and better focused, training

Two-thirds of those surveyed felt that there were not sufficient training opportunities for professionals and four-fifths felt that the current training did not cover the right topics.

The HR crisis in the UK film industry

One message came through loud and clear: the film industry has serious issues within its hiring and employment practices. Over half of the people surveyed raised issues around employment practices, unpaid work and diversity (race, gender and class).

Gender

Many respondents complained about the film industry's male-centric bias. My 'Cut Out Of The Picture' report earlier this year showed that women make up just 26% of producers, 15% of writers and 14% of directors of UK films (2005-14). Not only are women under-represented, but this situation is not improving. One respondent summed the situation up by saying:

Film & TV industries remain some of the most unequal, sexist work places in the country.

Age and race were also cited as areas of discrimination, but not to such a degree as gender. Whilst this could be read to mean that age and race are smaller issues, instead I fear that this reflects how few older and BAME people are in the industry, therefore they wouldn't even be on the list for a survey such as this one. I have an upcoming research piece on race which I will share in a few weeks.

Childcare

A related issue is the lack of support for parents working in the film industry. Data from Creative Skillset shows that only 14% of women working in film have children compared with 74% in other careers across the UK. Many asked for immediate action via regulation and changes to the tax rules governing freelancers. One industry professional pointed out that:

A director can deduct massages on set but not childcare.

Unregulated unpaid work

Unpaid ‘internships’ and ‘work experience’ placements are rife in the industry, despite being illegal. Minimum Wage regulations allow for unpaid work as part of an education course, genuine volunteering or charitable work but the vast majority of unpaid film ‘opportunities’ do not fall into any of these three categories.

Despite this, the general belief among my respondents was that enforcement is lax to non-existent. In a survey I ran with The Callsheet, 49% of UK television employers and 46% of UK film employers felt that new entrants should expect to work for free. Many felt that they should be expected to work for free for “extended periods” or longer (8% in TV and 20% in film). As one respondent put it:

[the UK film industry] constantly avoids paying the new people at the bottom, entry-level of the industry. As a result, only a very select monied few can afford to participate in the industry.

When these three issues are combined, it's clear that the UK film industry has far to go to bring its HR practices up to the standards we expect of a modern industry.

I shall leave the last word to this respondent:

That it is operating on a totally unfair, unjust system relating to access, routes of progression and retention which means very few people can participate and progress and that has a direct impact on the representation of society that we see on our screens which in such a heavily mediated society is a terrifying situation.

Epilogue

These findings may be relevant to the BFI consultancy but are not directed at the BFI. The topics mentioned above span the whole of our industry and, while the BFI is already taking action on many of the topics, these are not things we should expect them to unilaterally fix. It's easy to blame the largest body in UK film but, in truth, these are topics we should all be working to positively impact.

I don't have easy, quick solutions for the issues raised, but the first steps must be conversation and more research. Many of the industry's worst practices are a result of unquestioning reliance on old industry processes. As Brexit forces us to discuss what the future holds for UK film, hopefully we can also address the areas of concern listed above.