Has the way movies use dialogue changed?

What happens when you track dialogue patterns across 90 years of cinema? I ran the numbers on 60,000 films to find out.

Last week I was re-watching The Conversation (1974) with friends, and we all noted just how different the sound design felt to modern movies. The analogue tape machines stood out, but so did the footsteps, the music, the room tone, and above all, the sparse dialogue.

I finished the movie, wondering how atypical The Conversation was. And how all movies from the 1970s compare with modern ones in how they use dialogue.

At that very moment, as if a gift from the content sponsoring gods, I got an email from Audiio.com offering to support any research project I was working on. They provide royalty-free music for filmmakers and so the idea of a data project focused on sound was a perfect fit!

Audiio’s music library is built for real-world editing. Every track includes full stems, so you can shape the sound to fit tight dialogue or fast transitions. Get 70% off your first year with code stephenfollows at audiio.com/stephenfollows

I analysed subtitle files from over 61,517 films released from the 1930s to the present day. Subtitle files include timestamps for each line of dialogue, which allowed me to track how much dialogue appears, how quickly it arrives, and how tightly it’s packed within a film.

Films Are Using More Dialogue Than Before

Let’s start by counting the number of words spoken in the dialogue. The Conversation has just 3,452 spoken words, an average of 30.5 per minute.

That’s almost half the overall average across the full dataset, which sits at 6,697.

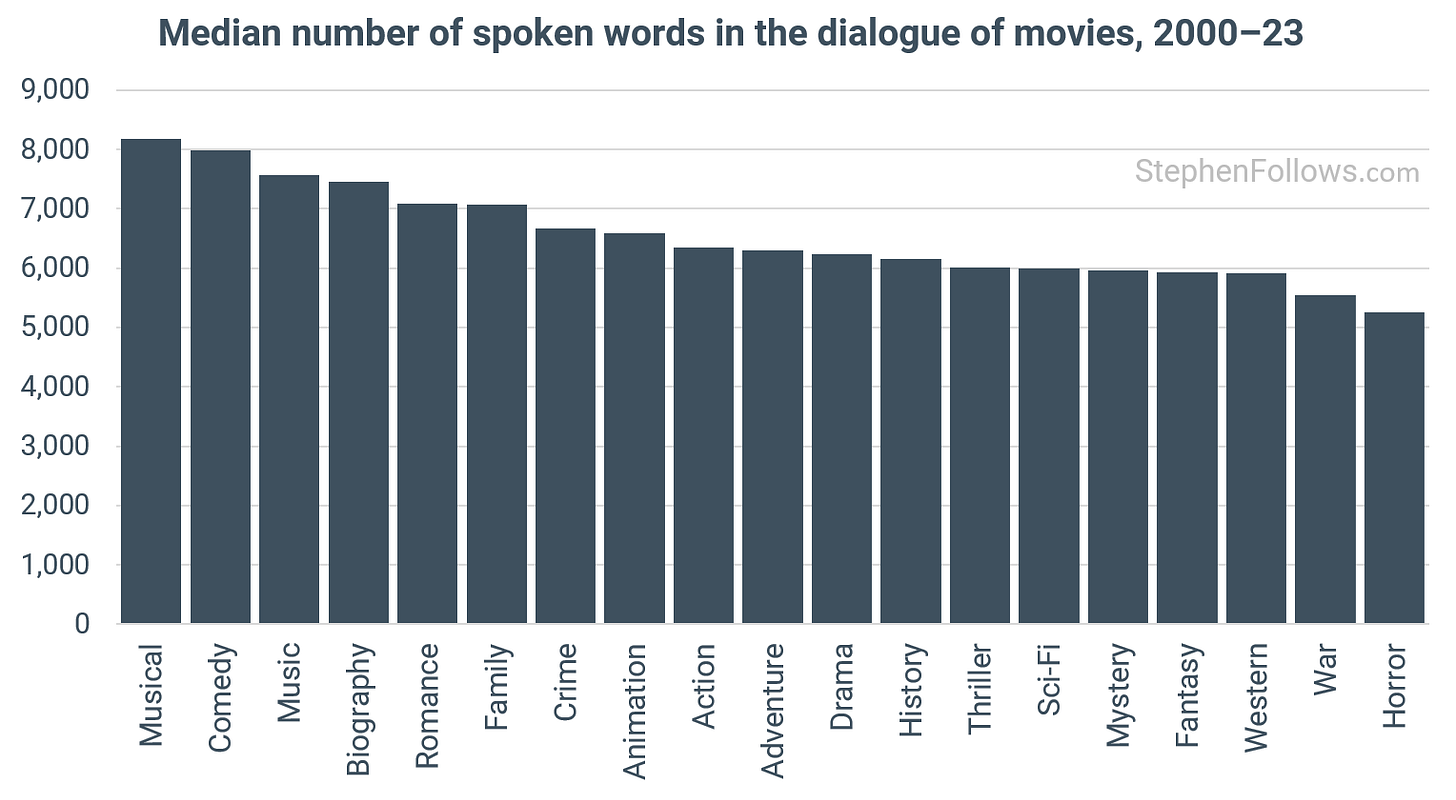

Looking at the median breakdown by genre, the films with the most dialogue tend to be musicals, comedies and music-driven stories. Genres with the fewest spoken words include westerns, war, and horror.

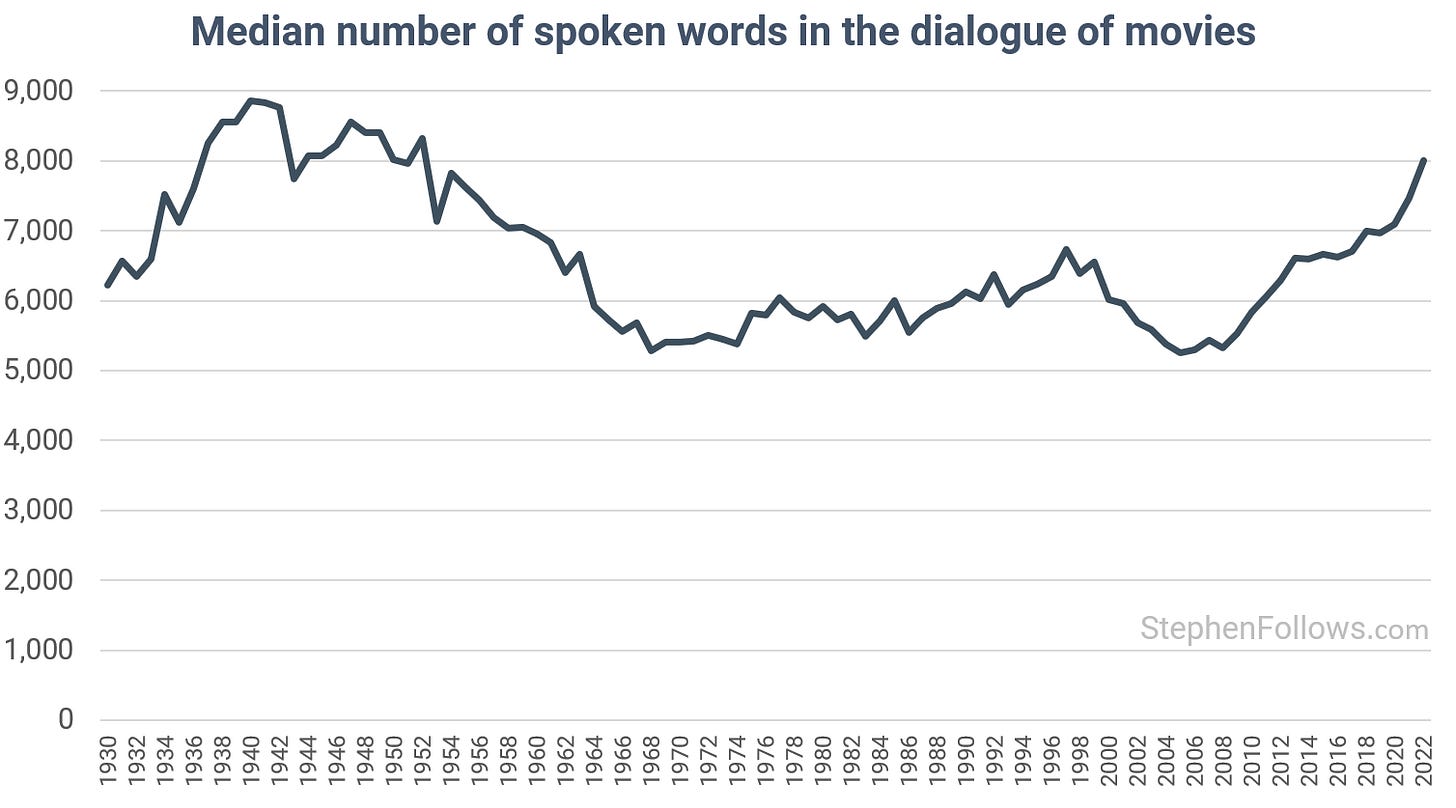

The average has shifted over time. Total words spoken peaked in the 1940s and then dropped steadily through the 1960s and 70s. In recent years, the volume has climbed again.

The Conversation fits neatly into that quieter stretch. It uses fewer words than the films that came before and the ones that followed.

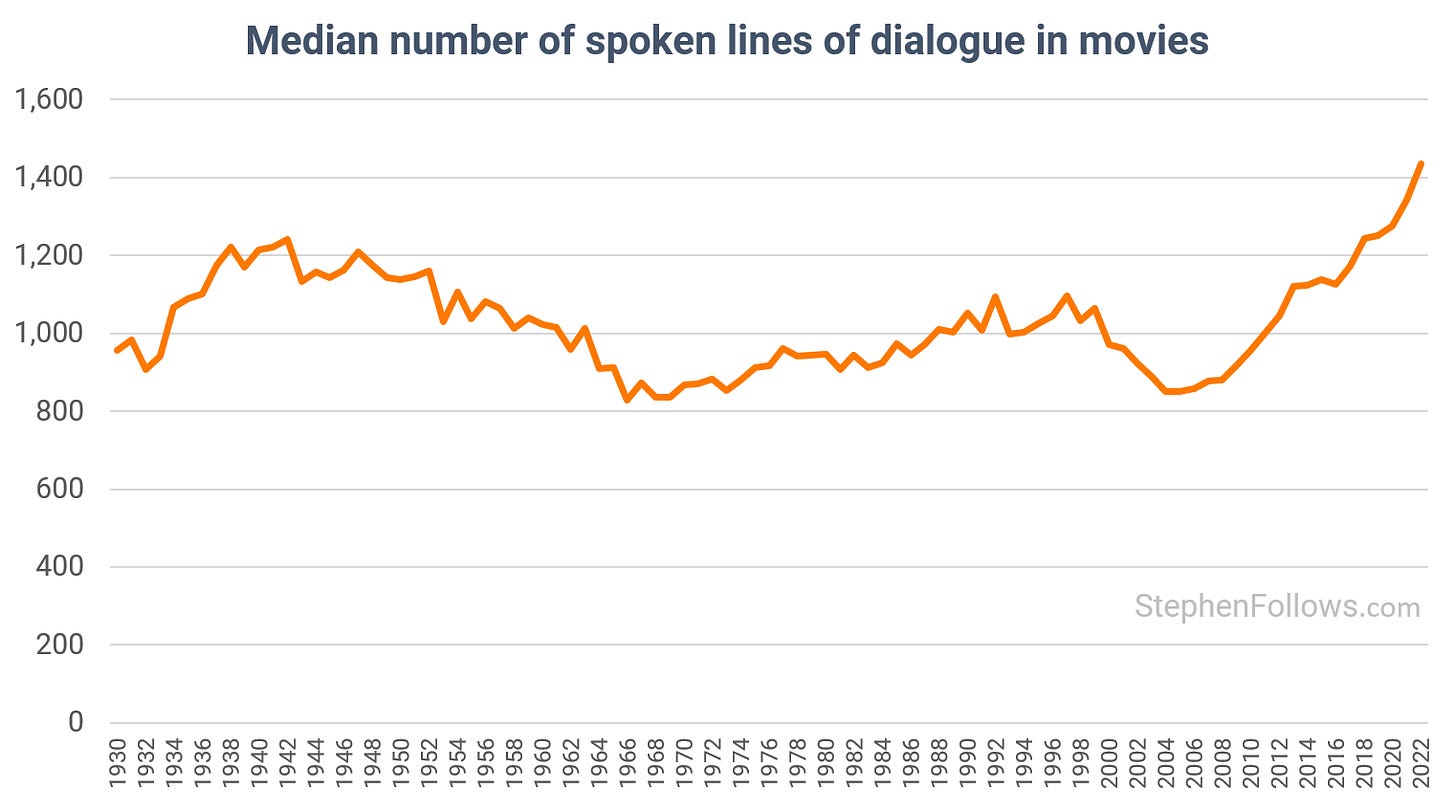

Interestingly, while the peak for total words came in the 1940s, those same films had fewer lines of dialogue than we see today. That tells us the lines were longer. Fewer pauses, fewer cuts, and more sustained monologues.

Modern films use more lines to say the same amount, or slightly more, suggesting a shift in writing style. Sentences are shorter. The rhythm is more broken up. Dialogue arrives more often, in smaller doses.

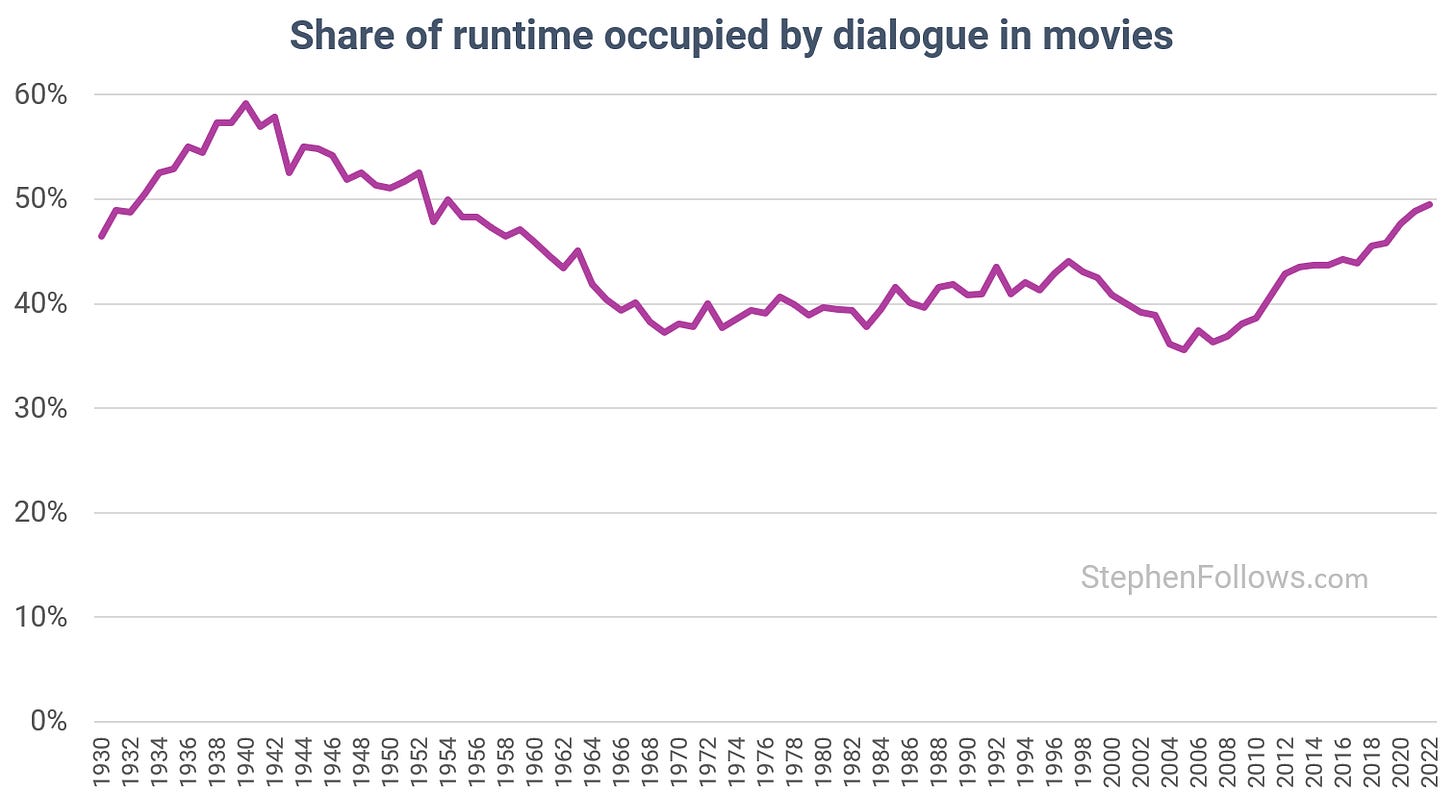

Dialogue Takes Up More of the Film

By comparing the dialogue timestamps with the total run time of each film, we can estimate how much of the movie is taken up by people speaking.

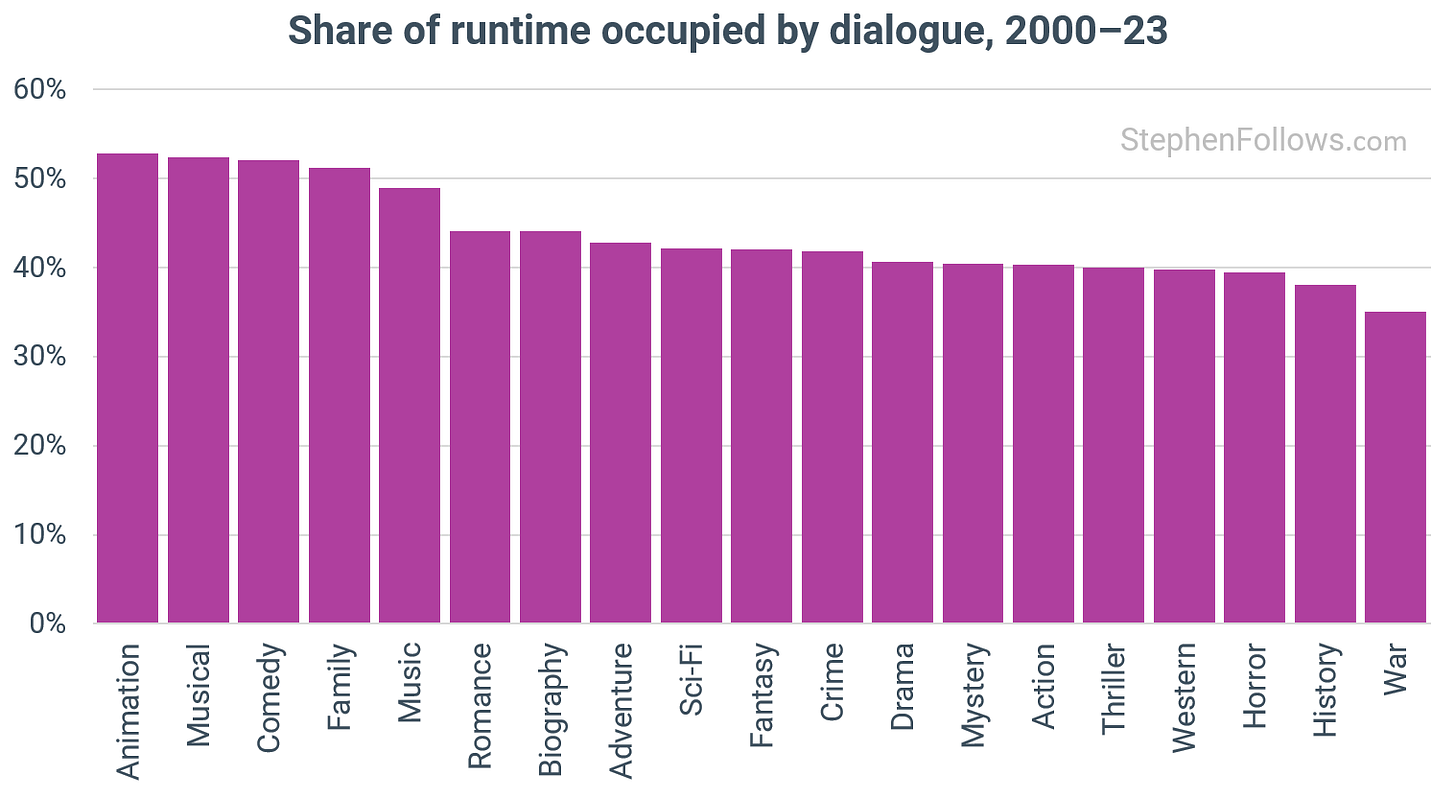

The pattern follows what we saw with word count. Films with shorter gaps between lines also tend to give more of their runtime over to dialogue.

Animation tops the list, helped by shorter average runtimes and tightly packed dialogue. Musicals and comedies also sit high on the list, with both genres often crossing the 55% mark. These films use speech and lyrics to carry much of the story and character work.

Early films had fewer camera moves and simpler sound design, so dialogue carried more of the storytelling. Film released in 1940 had 60% of their running time taken up by dialogue.

By 2005, the average share of screen time given to dialogue had dropped to just 35.6%. It has since climbed back and currently sits at just under 50%.

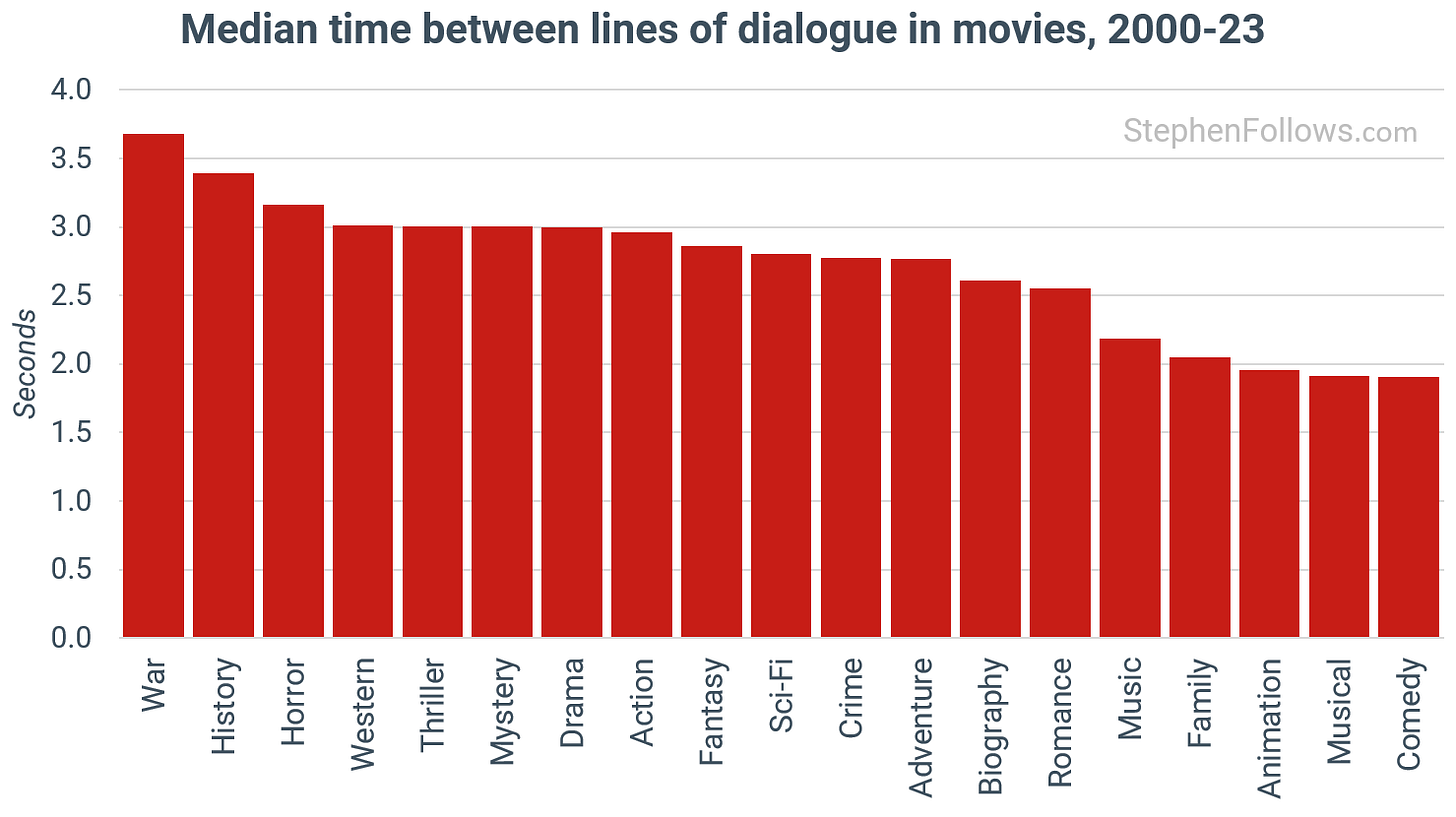

Films Leave Less Space Between Lines

Another way to think about dialogue is to measure the silence. Specifically, how long the gaps are between people speaking.

Across all war films, the median gap between spoken lines is 3.7 seconds. That’s the longest of any major genre. At the other end, comedies keep things much tighter, with a typical gap of just 1.9 seconds.

The numbers reflect the rhythm each genre tends to favour. A Quiet Place (2018) is built on silence. That silence is part of the story and the suspense. Turning Red (2022), by contrast, keeps the dialogue flowing almost constantly. Both choices make sense for the stories they’re telling.

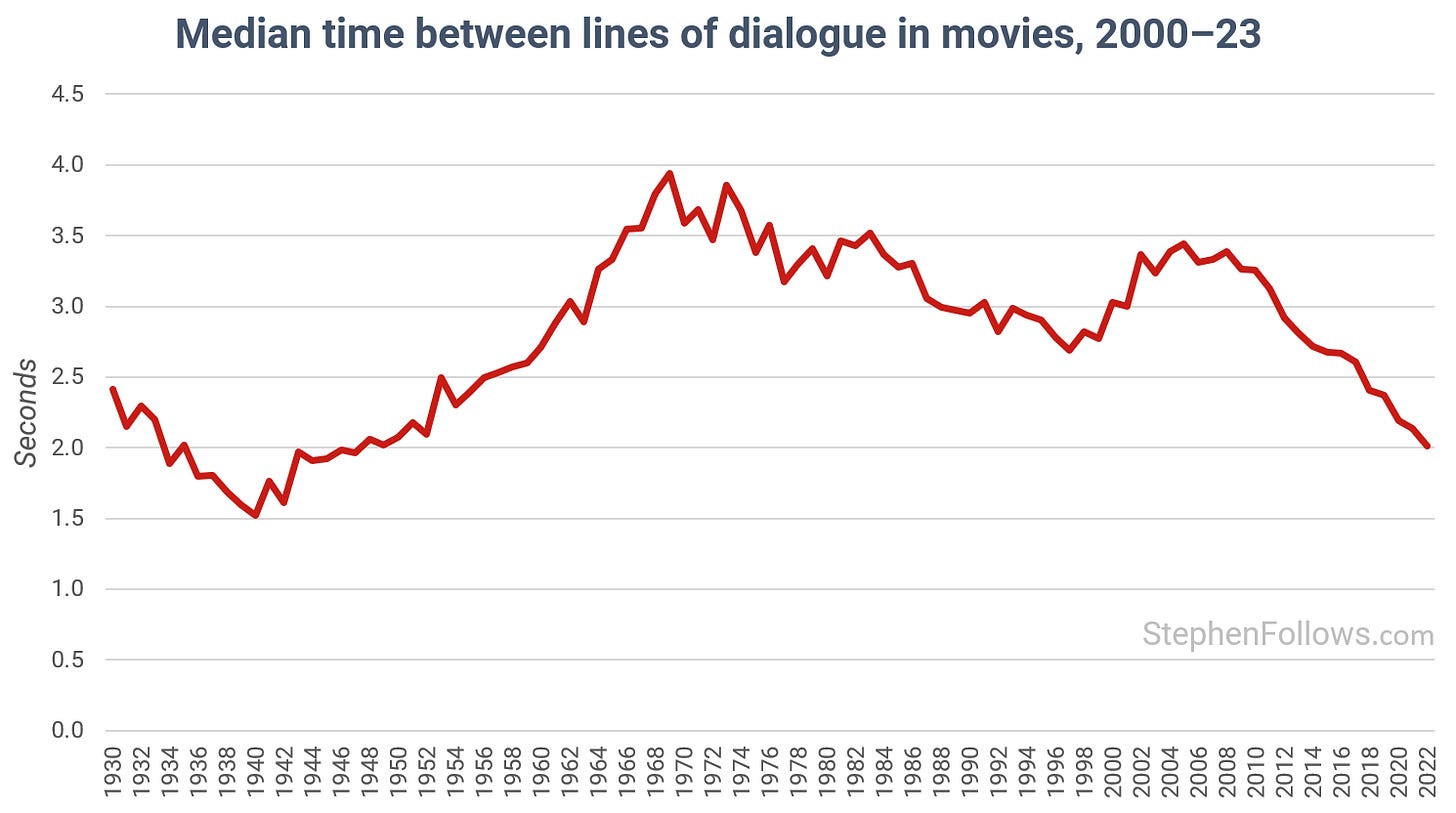

Over time, we’ve seen the dialogue gap shrink. In the early 1960s, it peaked at around four seconds.

Today, that has halved.

We’re not quite back to the briefest pauses of the 1940s, but the gap is heading in that direction. Back then, it was around 1.5 seconds. This made space for fast delivery, shorter lines and tighter pacing. We're now seeing similar rhythms return.

Dialogue Rhythm Is Getting Tighter

Writing, editing, acting and scoring all shape the rhythm of a scene. When there’s less space between lines, there’s less room for music, sound effects or silence to take the lead.

Shorter gaps force music to sit under dialogue rather than between lines. That changes how composers work. A cue needs to hit more precise timings. There’s less space for long builds or slow fades.

Speaking of cues, this is also one for a word from our sponsor:

This research was supported by Audiio. They run a curated music and sound effects library for filmmakers. Every track includes full stems. That means you can pull out the melody, strip the percussion, or use just the ambient layer. It’s helpful when you need music to fit around dense dialogue.

Plus their AI tools make it really easy to find the perfect piece of music.

They’re offering readers 70% off their first year of Audiio Pro. Use the code stephenfollows at audiio.com/stephenfollows

The data doesn’t show that all films have got faster. It shows there’s less time between one line and the next. The rhythm has changed. Dialogue arrives more often, with fewer pauses.

In The Conversation, the longest gap between lines is almost two minutes. But across the whole film, the average gap is 2.4 seconds. That’s actually shorter than the average in 1974, which was 3.7 seconds. The lines are brief, often clipped.

Here's a short stretch from about two-thirds of the way through the film:

MARK: Better start looking. MEREDITH: Harry. ANN: Well, what about me? HARRY: Why, why, what is she frightened of? MARK: You'll see. MEREDITH: Turn it off. ANN: You're no fun. You're supposed to tease me, give me hints, you know. HARRY: ...give me hints. MEREDITH: Harry, come here... MARK: Does it bother you? ANN: What? MARK: Walking around in circles. ANN: Look , that's terrible. MARK: He's not hurting anyone. ANN: Neither are we...

Film dialogue is shifting. There are more lines, delivered more quickly, and they take up more of the film’s running time. But in some ways, we’ve been here before. These patterns echo the pace and density of the 1940s.

Notes

It’s worth noting that what we’re tracking here is dialogue as recorded in subtitle files, not as written in the script. Subtitles may be edited for length, and long sentences often get split into multiple entries.

So a single monologue in the script might appear as several lines, or even fragments, in the subtitles. Given that today’s focus is on the volume and absence of dialogue, this isn’t a problem. But if you’re a screenwriter looking for guidance on how long your lines of dialogue should be, a better resource might be my 2019 study Judging Screenplays By Their Coverage, which looked at over 12,000+ screenplays.

Thanks again to Audiio for supporting this research. Their platform gives filmmakers access to high-quality music with full stems and powerful AI tools to find exactly what you need, fast. You can get 70% off your first year at audiio.com/stephenfollows with the code stephenfollows.

Thank you! Thank you! Thank you! Everyone who said my scripts have too much dialog can now officially suck it! 😀

I’ve been maintaining that films have a lot more dialog than people admit. It’s great to finally have data about the trends.