Has the word "horror" stopped being useful?

As horror films multiply and diversify, the label is collapsing under the weight of what it’s being asked to describe

An oft-repeated mantra among film distribution professionals is “Drama is not a genre”.

By that, they don’t mean that films cannot be dramatic, nor that there are not films you could call “a drama”. In fact, it’s the reverse - too many films could be classed as a drama, thereby making the term of little use.

The main function of a genre descriptor is to quickly convey to the audience what they should expect from a movie.

You say comedy, they expect to laugh.

You tell them it’s a romantic comedy and they expect to have their heartstrings exercised.

You say western and they have a clear idea of the setting of the movie.

And for a long time, horror brought forth a pretty narrow set of expectations.

However, times are changing and the horror genre of 2025 is not what it once was.

On Tuesday I was part of an event called “The Business of Fear” with Jason Blum and other senior figures from Blumhouse and Atomic Monster, where we unpacked trends across modern horror. I wanted to share the key points here to ensure the topic is open to all and to continue the discussion in public.

Let’s start by setting the scene…

It emerged from the shadows…

Before cinema, “horror” described physical revulsion and after World War I, also became a shared shorthand for trauma. This means that by the 1920s, it had emotional and cultural weight that made it ripe for cinema.

Early films with unsettling themes were labelled “weird” or “mystery” rather than horror. Critics used “horror” occasionally, but not as a genre. Even Nosferatu and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari weren’t called horror at the time.

That changed in 1931 with Dracula and Frankenstein. Universal initially pitched Dracula as a mystery, unsure how audiences would react. But viewers and critics called it horror and the label stuck. The studios chose to embrace then term and by the end of the year, horror was a recognised genre.

The next year, the British censorship body, the BBFC, introduced an “H” certificate, and the Hays Code in the US soon limited what horror could depict. The word now shaped how these films were made, marketed and seen.

Horror is having its boom moment

Genres rise and fall depending on what the world wants to watch.

Bright, happy and optimistic musicals dominated in the post-war years, and westerns thrived during America’s frontier obsession.

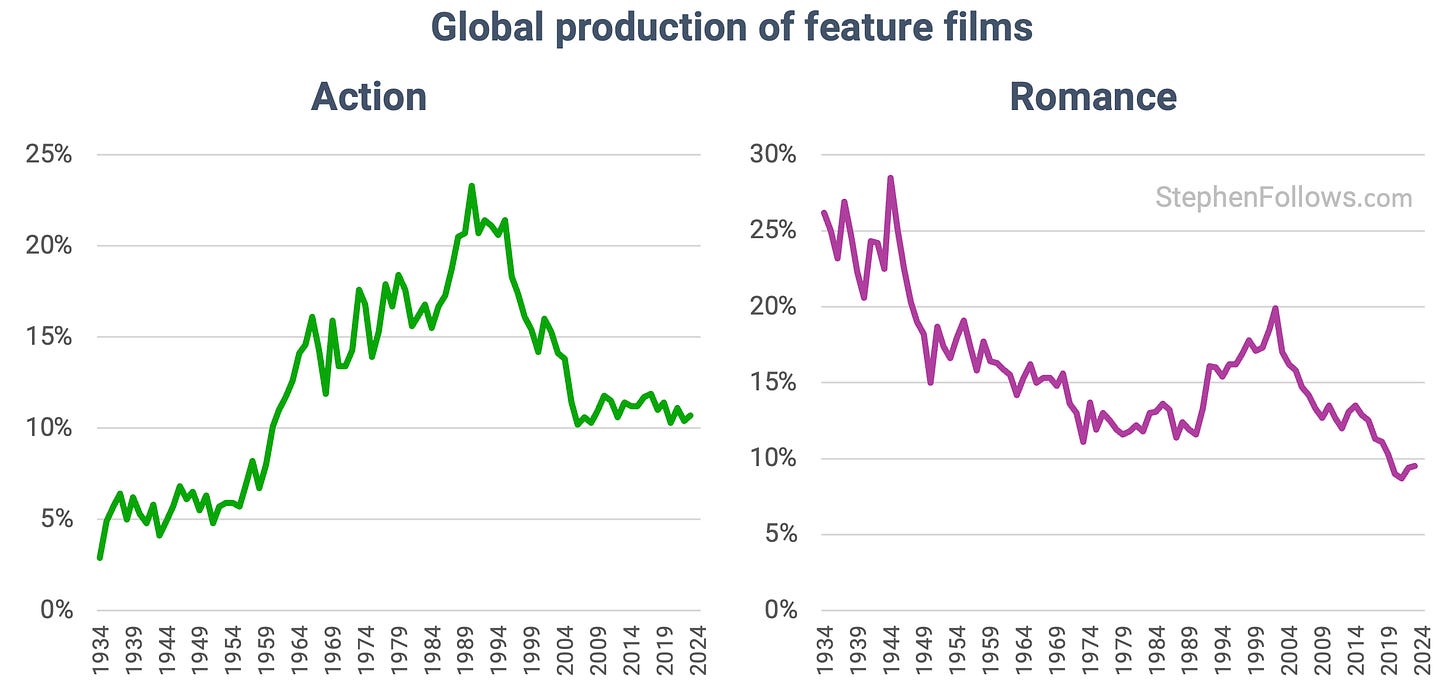

Action films exploded in the 90s and early 2000s, and other genres have seen peaks and troughs (regular readers will know of my research into the decline of romance on the big screen).

Horror is now clearly in its moment. The share of horror films in global production has tripled since the 1980s.

In 2024, horror generated more theatrical revenue than drama, comedy or thriller.

This is where things get complicated. For the chart above I included Beetlejuice Beetlejuice as horror - a description some will agree with, while others will consider it juicing the figures.

One label now covers too much

When horror accounted for just a few percent of production, it made sense to use a single genre tag. Now it covers a wide spectrum of tones, styles and audience expectations.

It includes gore-heavy franchises, quiet psychological studies, family-friendly thrillers and arthouse allegories. In practice, calling all of them horror is about as useful as calling them movies.

This is the same reason professionals avoid using the term "drama" as a working category. It doesn't exclude enough to be helpful.

Horror has become too large to be a label. It now works better as a section heading, with the real work happening at the next level down.

Horror is already subdividing

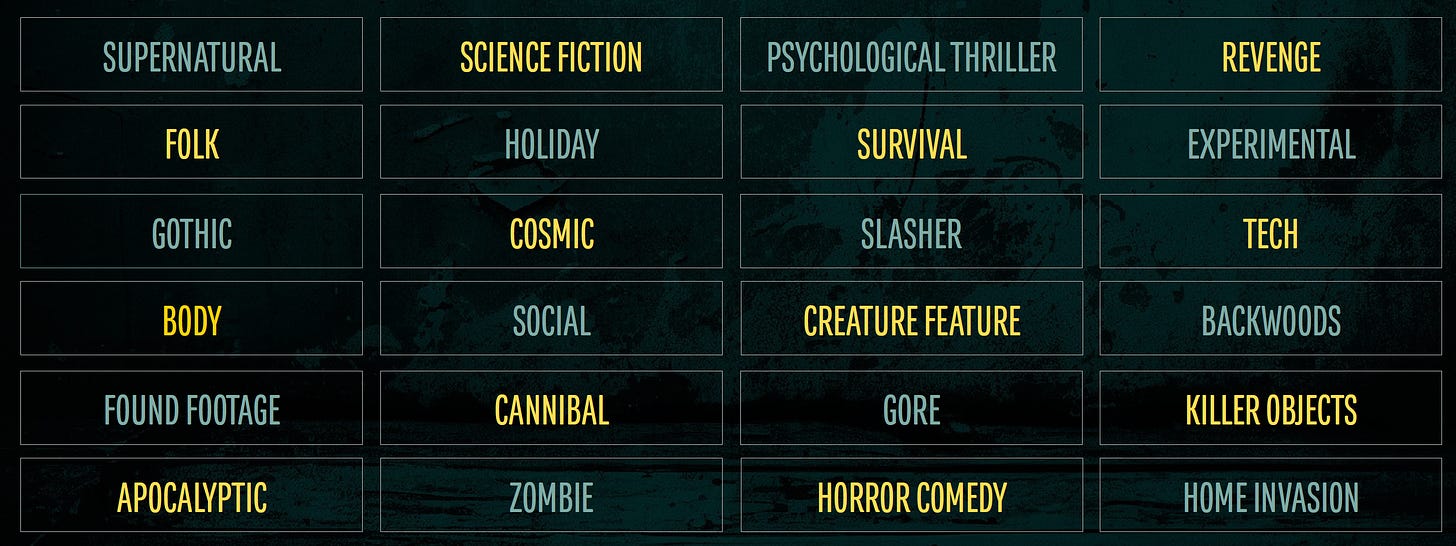

When I came to research my Horror Movie Report last year, I had to decide how I would subclassify horror. After a lot of research and number crunching I settled on 11 sub genres, allowing for movies to fit into more than one.

Later in the year, Blumhouse reached out to compare notes. In their research they settled on 24 subgenres.

And I’m sure other organisations and people will have their own list of what is and isn’t a subgenre. The aim here is not for us all to agree on a single, strict nomenclature but more to reflect that subdivisions are a real-world necessity.

Subgenres

Whichever criteria you use, once you start to pick between the types of horror subgenres, fascinating patterns emerge.

As we saw with top-level genres, the ebb and flow of different types of horror movies seem to reflect the age they were made in. Post-apocalyptic horror tends to spike during periods of instability. Survival stories and found footage surged during economic uncertainty. Gothic and monster cycles come and go, but rarely vanish completely.

Why this matters

This isn’t the first creative media which has faced the challenge of labels outgrowing their original purpose. In the middle of the 20th-century, referring to “popular music” was enough for people to know what you were referring to. However, now Spotify offers a cornucopia of subgenres and micro-classifications for music lovers.

As well as better describing the creative works, the subdivisions also tackle another problem which happens as a label swells - audience fragmentation.

Someone who enjoys psychological horror may have no interest in body horror. Fans of slow supernatural films may avoid high-speed slashers. Trying to talk about horror as a single category misses this entirely.

The word horror no longer tells us what a film is trying to do, how it feels, or who it’s for, meaning that the term alone has stopped being useful.

What is a horror movie, anyway?

The rabbit hole of an exact definition of a horror movie is way deeper than I have presented thus far. Here are some thoughts for you to ponder and discuss among yourselves:

The horror aesthetic is often used in children’s movies, such as Hotel Transylvania and The Addams Family.

Similarly, pure comedies are sometimes set in horror worlds, such as Dracula Dead and Loving It, or What We Do In The Shadows.

The line between a disgusting thriller and a horror movie is so thin as to subjective. Examples would include Se7en and The Silence of the Lambs.

The action genre is littered with movies following the horror playbook, from Jurassic Park to War of the Worlds.

I’ve heard it argued that many films for kids are plots lines ripped directly from the horror world, without attribution. Examples would be Disney’s Pinocchio being a simple retelling of Frankenstein, or the Charlie and the Chocolate Factory being a pretty bog standard slasher, bumping off it’s characters one at a time based on their moral failings.

Epilogue

No-one knows when horror movies will stop their inexorable rise (or if they continue their current trajectory, all movies made will be horror by the year 2104).

But even if horror’s plateau comes about soon, they are already such a large and varied set of films as to make just the word “horror” a little dead on arrival.

The Horror Movie Report

If you want to dig deeper into the horror genres(s), then grab a copy of my Horror Movie Report

It’s a massive collection of research, statistics, and spreadsheets. It’s packed with insights on everything from horror’s financials to its evolving subgenres.

Read more at HorrorMovieReport.com

i find it curious that "found footage" is considered a genre – i see it as more as a technique or style, like "animation" – found footage can be supernatural, zombie, gore etc

are there any found footage horror-comedies? – start would be cool