This is an article I have wanted to research and write for a long, long time. I finally had a moment to sit down and crunch the numbers - I hope it helps in the understanding of Hollywood economics. It's a lengthy one, so grab a cup of tea.

Every six months or so, someone on my Facebook feed will share a list of "The Most Profitable Movies of All Time". These lists normally use the budget of the movie and the amount of money it collected in cinemas worldwide to conclude how much "profit" the movies made. For example, "Paranormal Activity cost $15,000, grossed $193 million and so made a profit 1,286,566%". Another popular fallacy is that when a movie with a $100 million budget crosses $100 million at the box office it is considered to have "recouped".

While I understand why people fall for such over-simplifications, they have no real connection with how movies actually make money. Therefore, in an effort to demystify the film recoupment process I'm going to write a few articles looking at how movies make a profit. In the coming weeks, I'll look at movies with smaller budgets but let's start with the big ones - Hollywood blockbusters.

"We're going to need a bigger boat"

Almost as long as there have been movies, Hollywood has relied on huge-scale productions to bring in the big bucks. Movies like Gone With The Wind, Ben-Hur and Cleopatra attracted large cinema audiences with a promise of cinematic spectacle. However, the first 'blockbuster' in the modern sense was Jaws (1975). The film broke box office records and created the modern summer blockbuster as we know it today. Its wide national release supported by blitz advertising created the first 'event movie' and became the template for later blockbusters including Star Wars (1977), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) and E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982).

In the past few decades, Hollywood studios have sought to perfect the model, and in so doing have massively increased the cost of making and promoting such movies. Modern blockbusters are often referred to as 'tentpole movies' as they represent the most important products in a studio's release calendar. As the films have grown, so too have the spoils on offer. Last year, Jurassic World earned a whopping $1.67 billion in cinemas worldwide; quite a haul for a movie which cost $150 million to make. But after they recouped the original budget, how much of the remaining $1.52 billion turns into profit?

For today's data, I am using a dataset of 29 Hollywood blockbusters, all of which cost over $100 million to make. The financial figures come from a few different sources within Hollywood studios, which I discuss in the Epilogue section at the end of this article. For now, just know that these figures are real-world, correct and relate to Hollywood movies released in the past ten years which cost over $100 million to make. (Note: The images and posters used in this article do not relate to the movies in my dataset - I've picked them because they're nice images which seem to fit in well with the text).

What's the average cost of making and selling a Hollywood blockbuster?

Before we can get to the numbers, here are some key phrases you'll need to know to understand Hollywood economics...

Domestic - The release of the film in America and Canada, also known as "North America".

International - The release of the film in the rest of the world combined. In some cases, studios will only have the rights to release a movie domestically, with another company picking up the international rights (or vice versa). For example, Paramount have the rights to distribute The Adventures of Tintin domestically while Sony controls the international rights.

Theatrical - Relating to the cinema release (i.e. in movie theatres).

Home Entertainment (or "Home Video" or "Home Ent") - The release of the film on DVD, Blu-Ray, previously VHS and online streaming services.

Pay TV - Subscription television channels. In the UK this includes Sky Cinema and in the US cable networks such as HBO.

Free TV - Free to air television, typically either public service broadcasting or ad supported. In the UK this includes the BBC and in the US ABC.

Video on Demand (VOD) - Online streaming services (such as iTunes, Netflix and Amazon Prime).

Pay Per View (PPV) - An old form of VOD which is still active in some places involving the viewer paying to watch an encrypted, scheduled transmission of the movie.

Ok, enough terminology - let's start our journey into what Hollywood blockbusters cost and what they make back.

The first huge cost - The budget

The starting point for working out the final costs of releasing a movie is to look at how much it cost the studio to shoot the film (i.e. the film's budget). In the industry, this is often called the 'Negative Cost' as it's the cost of producing the very first version of the film (which used to be a film negative). This includes...

Development - Getting to a final script

Pre-production - Building a team and planning the shoot

Production - Shooting the movie

Post-production - Editing, visual effects, sound design and music.

It will include most of the cast and crew's wages but probably not the full amount paid to key personnel, such as the director or lead actors. These people may get additional money based on how well the film performs (known as "Contingent Compensation") or a share of the money leftover once all the bills are paid (known as "Profit Participation").

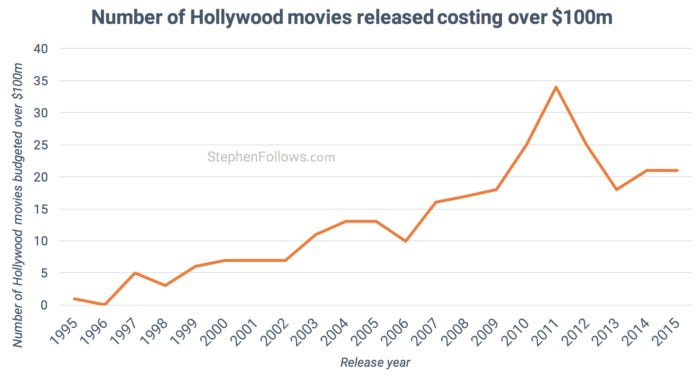

Budgets have been rising in recent decades, well above inflation. In the ten years between 1995 and 2004, there were 60 Hollywood movies released which cost over $100 million. In the following ten years (2005-14) this rose to 197.

The studios found themselves in an ever-increasing spiral whereby blockbusters were getting more expensive to make, meaning that they needed to spend more on marketing to offset the risk, which meant they needed to ensure their films are the biggest of the season, which inflated the budgets and the circle continues to turn.

Many feel that this cycle is not sustainable and a few years ago some industry watchers felt that a huge crash was imminent (Steven Spielberg and George Lucas both predicted an industry 'implosion'). In the end, it seems that Hollywood has just reigned in spending with 2014 and 2015 having just 21 movies apiece, far below 2011's high of 34.

Discovering the size of a film's budget

Although technically a secret, a film's total budget often leaks out and they are easy to find online (for example, Googling the phrase "Jurassic World budget" reveals that it reportedly cost $150 million to make). The information available online is normally a mix of true figures which have leaked and educated guesses by industry experts.

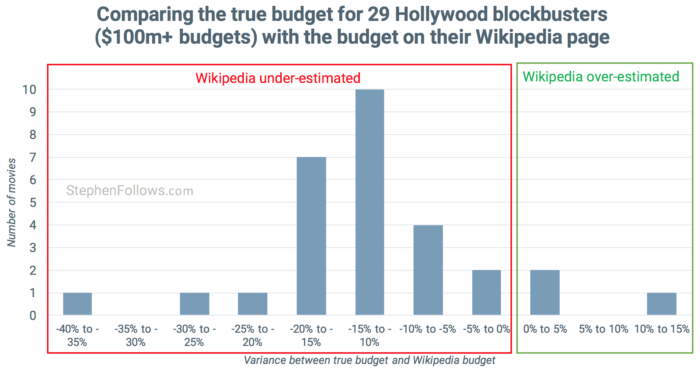

The studios often try to hide the true cost of a movie, in order to make themselves seem thriftier, smarter or more in control than they actually are. I performed a quick check for the 29 blockbusters I have inside data on compared with their budgets listed on Wikipedia. 90% of the films cost more than their Wikipedia budget with only three costing less than is declared on Wikipedia.

So the average $100m+ Hollywood blockbuster actually cost $19 million more than is stated on Wikipedia (i.e. 12.5% more).

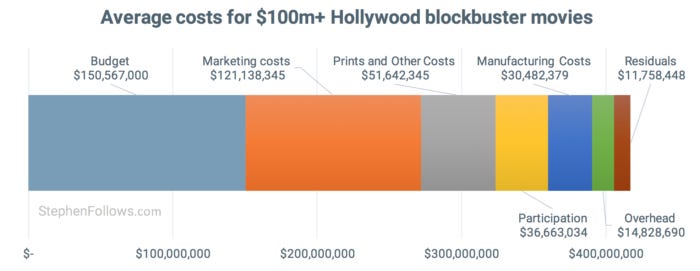

For reference, the average budget for the blockbusters in my dataset was $150,567,000.

Other costs of making a movie

Releasing a Hollywood blockbuster involves far more than just creating 90 to 120 minutes of footage. Some of the other costs involved in making and releasing a film include...

Marketing - It could be argued that success in the business of Hollywood blockbusters is more dependent on the art of marketing than the art of filmmaking. This is the biggest category of costs for a movie, outside of the budget. Most Hollywood blockbusters only have one or two weeks when they are 'The Big Movie' in cinemas, so studios need to build and channel the awareness / excitement for a movie to ensure that everyone goes to see it during this period.

Prints - The physical copies of the films which are given to cinemas. Historically, they were on 35mm celluloid film but today most countries use a hard drive with a specially encoded digital video file called a Digital Cinema Print (DCP). This hard drive has a huge copy of the film (10s or 100s of Gigabytes) and a tiny file which controls the permissions to the large video file. This means that hard drives can be shipped to cinemas in advance, without worry that the film will be viewed ahead of its official release. Complex permissions can be set, permitting screenings only at certain times or on certain digital projectors. Also, copies of the film in other formats will need to be created to give to third parties distributors and exhibitors, such as TV stations who broadcast the film.

Residuals - Unions for the cast and crew have agreed deals with Hollywood studios which ensure that their members receive additional payments from the income the film generates.

Financing costs - These can include costs involved with borrowing money to make the film (interests and brokerage fees) and currency conversions (for overseas shoots).

Overhead - Studios charge their own productions an overhead fee which covers the time studio staff spend on the project, the costs of deals which apply to all films the studios make and the benefit a production is regarded as receiving from operating under the studio brand. It may seem strange to charge oneself money but these costs come off before "profit" is calculated, meaning that productions which pay an overhead have smaller official profits, meaning that the studio has smaller cheques to cut to people with profit participation deals. The old joke in Hollywood is that the studios charge overhead on interest and interest on overhead (and if you find that funny you really are down the rabbit hole of Hollywood economics!)

Looking at my dataset we can see the average costs breakdown below...

To give you a little more detail and context, below are some notes on each of the main cost areas...

Marketing costs

Is it often claimed that marketing a Hollywood movie can cost up to twice of the cost of the film's budget, however from the numbers above we can see that this is untrue. Across my dataset of $100m+ movies, the average budget was $150.6 million and the average combined marketing spend was $121.1 million (i.e. 81% of the budget).

When expressed as a percentage of the total costs involved with making and selling a movie, marketing accounts for an average of 29% of costs. Across my dataset, the largest proportion of total costs going towards marketing was 40% and the lowest was 24%. It seems that the larger a movie's budget, the smaller a percentage marketing makes of the total cost. While this may at first seem strange (we normally associate bigger movies with having bigger marketing budgets), consider that even films on the lower end of my dataset have budgets over $100 million and so their marketing efforts will be pulling no punches. In short, once you make a movie over $100 million you're already using saturation marketing tactics so if you double a movie's budget you can't really double the marketing spend.

Physical delivery costs

The physical costs of creating and shipping prints to cinemas and of creating and shipping physical media to stores account for an average of $67.8 million. Judging the correct number of prints and units to manufacture is a key part of the planning done by the studios. If they order too few then cinemas and stores will have to turn away customers in the all-important first few weeks of release. If they over-order then their costs increase and they are left with annoyed cinema owners and large quantities of unsold units. Most units are sold on a 'Sale or Return' basis meaning that if studios over order then it's their problem, not the stores.

In 2005, Dreamworks overestimated the number of Shrek 2 DVDs they would sell in the US by 5 million units. This caused the studio to missing their quarterly earnings target by 25% and their shares fell as a result.

Profit participation

The average $100m+ Hollywood blockbuster will spend $36.6 million on contingent compensation and profit participation. This typically goes to the key 'creatives' involved in making the film - namely the director, producer(s), writer(s) and key cast.

Giving these people a share of the income is a good way for the studio to hedge against poor box office performance and it also defers the moment they have to pay up. Key talent often seek 'participation points' as a way of increasing their income and to share the spoils if a film performs much better than expected.

On the flipside, studios have got rather good at using creative accounting techniques to show that they made a loss on paper in order to get out of paying such fees. In 2010, a leaked profit participation report from the fifth Harry Potter film showed that two years after the film's release, Warner Brothers was claiming that the picture had lost $167 million. Other movies hit with such claims are the three Lord of the Rings films (which combined grossed almost $3 billion in cinemas worldwide), My Big Fat Greek Wedding, Spider-Man, Return of the Jedi, Coming To America, JFK, Fahrenheit 9/11 and Forest Gump, to name but a few.

The movie in my dataset which gave the largest share of income to participants gave 18%. It's worth noting that participation isn't always dependent on there being profits. As people get wise to the studios' game of creative accounting they are asking for more than just "a share of the profits". The biggest names will demand 'First Dollar Gross' deals, which give them a share of every dollar earned, calculated before costs are taken off. On average, the films which lost money in my dataset still paid out 5% of their income to participants (profitable films spent an average of 9% of their income on participants).

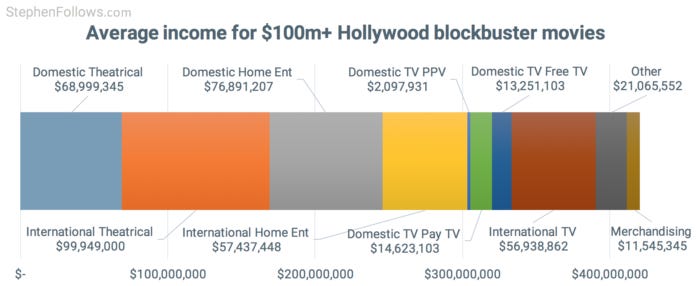

How do Hollywood blockbusters earn money?

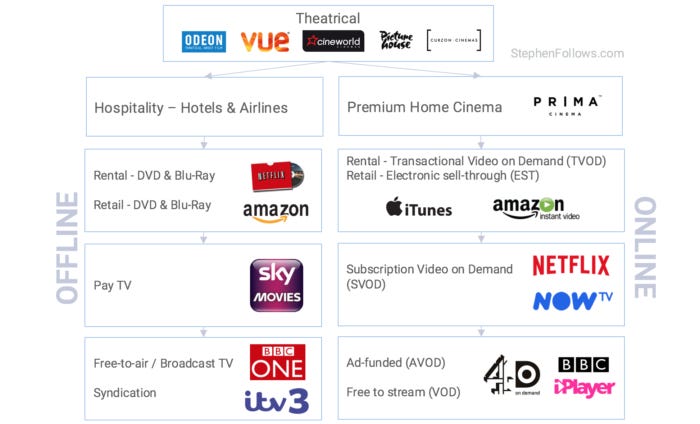

With each "$100m+" Hollywood blockbuster costing an average of $417 million to make, there had better be some serious income to reach profitability. Fortunately, Hollywood is rather good at squeezing every penny out of a movie, ensuring that the target customer is given many chances to pay to see it. Before we look at the financial figures, let's talk briefly about the journey a movie goes on to earn its money.

Movies may start in cinemas but they are far from the only place they earn money. Each stage at which a movie reaches a new type of platform (i.e. DVD, TV, etc) is called a "Release Window". In recent years release windows have shifted around (including the elimination of a previously-profitable exclusive window called "Video Rental" - remember renting a VHS at Blockbusters, anyone?) but most Hollywood movies follow the same path.

How much money do Hollywood blockbusters make?

Using my dataset of $100 million+ movies, I can share how much each of the sources of income contribute towards the bottom line.

Do Hollywood movies make money?

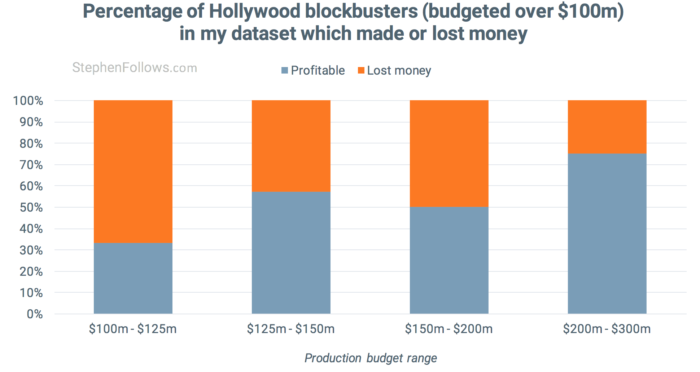

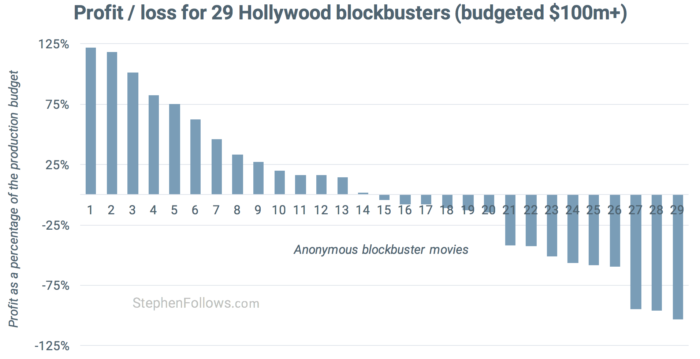

Of the 29 Hollywood blockbuster movies I studied, 14 generated a profit and 15 lost money. It's impossible to know if these stats hold true for mega-movies in all of Hollywood but I suspect they do, due to the way my dataset was created (see Epilogue).

Note: The following discussion of profit uses this formula: all revenue received by the studios from a particular movie minus all costs they internally attribute to that production. This is an important distinction as a movie which has only officially broken even could still have provided a large amount of income for the studio via the charging of distribution fees, overhead and financing costs (see above for the section on Hollywood's creative accounting).

The smallest movies within my dataset (i.e. those budgeted between $100m and £125m) had the poorest record of profitability, with just a third making money. Conversely, three-quarters of the movies with the biggest budgets ($200m upward) generated a profit.

So rather than looking at individual films, let's look at the big picture. Imagine you are an investor who put in 1% to all the films in my dataset in return for 1% of the profits. For ease, we'll assume that you're contributing towards all costs, you receive a share of all income and that the studios have taken pity on you and (for some unknown reason) decided to be honest with you about the numbers. Would you have made a smart investment?

Here are the combined financial figures for all 29 Hollywood blockbusters (budgeted over $100m)...

Total combined budgets: $4.37 billion

Total combined costs (including budgets, marketing and all other costs): $11.52 billion

Total combined income (from all revenue streams): $11.95 billion

Profit across all movies: $428.9 million

An average profit of $14.8 million per movie

That means for your 1% investment you would have spent $115.2 million, received $119.5 million back and made a profit of $4.3 million (i.e. a profit margin of just 3.7%). Considering that there is a delay between when you put the money in and when all revenue has been recouped, I think it's certainly possible to imagine that you would lose this 'profit' to inflation.

If instead of playing with Hollywood you invested that same money in a standard high street bank paying 3% annually, over ten years your $115 million would become $156 million (an increase of 35%). And I am sure this is a fairly low return for that kind of cash.

Maybe instead of taking 1% of all the movies combined, you could try and spot the winners ahead of time. Let's have a look at how the profit splits between the individual films...

So if you managed to put all of your money into 'Movie 1', then you would have a return of 122% (i.e. a $265.3 million return on an $119.5 million investment). The only problem is - how do you spot the hits? Hollywood currently employs the smartest, best informed and most profit-focused people in an effort to exclusively make profitable movies and yet half of their movies lose money. In fact, their combined best efforts only produce a 3.7% profit margin.

Correlations and curiosities

Before we leave the mad, mad economics of Hollywood blockbusters, let's have a look at some interesting questions. (If you have a question not listed below, leave it in the comments at the bottom of the page and I'll do my best to answer it from the data).

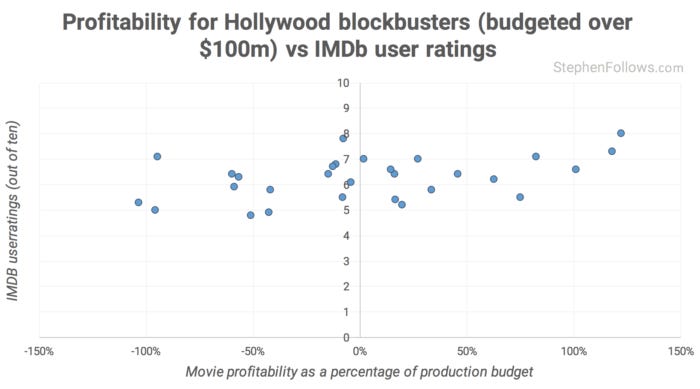

Q1: Are the films that make money better than those that lose money?

Yes, but only by a very small margin. The average Metacritic score (i.e. average of film critics out of 100) for profitable films was 55 and for unprofitable movies it was 49. Similarly, IMDb audiences rated the profitable films an average of 6.5 out of ten and the loss-making films an average of 6.1.

So it doesn't seem as though the Hollywood studios have any financial incentive to make their films better. Shame.

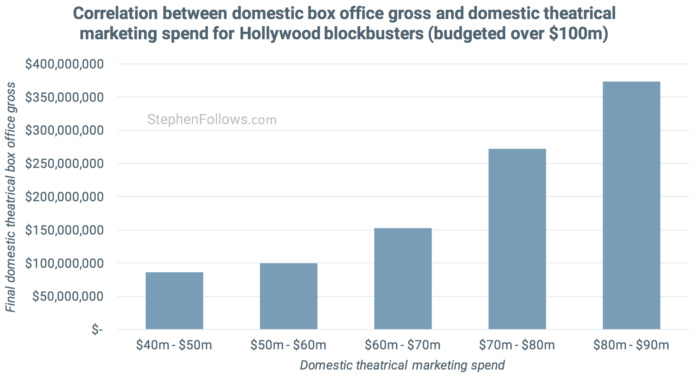

Q2: Does the amount they spend on marketing correlate with financial success?

In answering this question we have to be careful not to fall foul of the Statisticians' Mantra that 'Correlation is not causation'. Studios don't have to lock in their marketing commitments until they get close to the movie's release date and so it could be that they choose to double down on the marketing when they know they have a film which is likely to perform well. Likewise, if they think they have a real turkey on their hands they could dial back the marketing spend so as not to throw good money after bad. From this data, we can't tell why the correlation exists.

However, we can say that, yes, movies with the biggest marketing budgets do seem to gross the highest amounts at the box office.

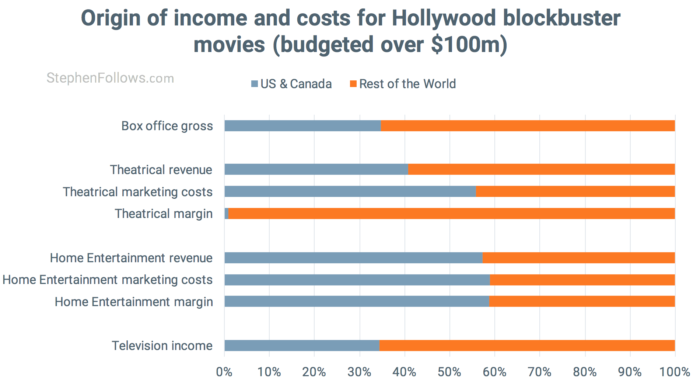

Q3: How important is the international market, compared to North America?

Hollywood makes blockbusters for global consumption and in recent decades the share of the money the studios have received from countries outside the US and Canada has grown considerably. In theory, increased international business comes with increased charges as much of the international film business is conducted through third parties, which adds cost and complexity. Added to this, studios are less likely to make missteps on their home turf as they can be on-hand to scrutinise everything to a greater extent. So, does this 'home advantage' make the domestic market more lucrative?

Well, it depends on which part of the process you look at. Below you can see the origin of revenue and costs for the blockbusters in my dataset.

As you can see, the majority of the money collected at the box office does indeed come from countries outside of the US and Canada. However, studios spend a higher proportion of their marketing money in North America. This could be for a number of reasons including the higher cost of advertising in America, the temptation to spend more in the country which studio execs actually live in and because the US is often the first place a movie is released and the media enjoy reporting on huge opening weekends (and decrying massive flops).

What's fascinating is that once you deduct the release and marketing costs (known as the "Prints and Advertising" or "P&A") almost all (i.e. 99.1%) of the theatrical margin left over comes from outside North America. This is the result of high fixed costs involved in releasing and marketing a movie in North America, the paper thin margins in the business (as we saw above, it's under 4% across all these movies) and the more reliable nature of international returns. Together, they mean that only 12 of my 29 movies made money at the domestic box office, whereas 20 made money at the international box office. Alongside this, the losses at the domestic theatrical market were much worse than internationally. The poorest performing movie at the domestic theatrical market lost $49.3 million whereas the poorest performing film at the international theatrical market only lost $14.8 million.

So Hollywood looks to the international market with glee because...

It's cheaper to market movies internationally, with the average movie in my dataset costing $55 million to market in the US and Canada and $44 million for every other country the film was released in combined. For a sense of scale, IMDb lists release dates for Avatar in 69 countries, and I suspect the real number is slightly higher.

The margin is more reliable and less prone to huge theatrical losses. As we saw above, the risk associated with releasing a big movie in North America is far greater than that associated with its international release.

It has the most potential for growth in the near future as the North American market is saturated with cinemas and movies. For example, between 2009 and 2013, cinema admissions in China rose by 239%, whereas in the US over the same period they shrunk by 5%. You can read more about the enormous growth in the movie business in China here stephenfollows.com/film-business-in-china

Q4: Is there a rule of thumb for guessing which Hollywood blockbusters are in profit?

In the UK, the BFI developed a rule of thumb which stated that a movie was reasonably likely to be 'profitable' if it generated twice its budget at the global box office. They reached this conclusion by studying the full financial records of the movies they were involved with and also checking their hypothesis with independent professional film financiers. But their dataset would have included few (if any) films budgeted over $100 million, and so it's interesting to see if it also applies to my dataset of Hollywood blockbusters.

So the question is... If we only had two pieces of information - the global box office gross (as reported on Box Office Mojo) and the production budget (as reported on Wikipedia) - how accurately could we guess how many $100m+ movies made money?

Well, you'd be right 83% of the time. Using this rule, I was able to correctly identify all of the profit-making films and correctly identify ten as loss-making, however, this system incorrectly marked five loss-making movies as being profitable. (I also tested the theory against the true budget figures due to the fact that Wikipedia budgets are mostly inflated, as previously discussed, but this only improved accuracy to 86%). In short, the rule works in around four out of five cases. Not as reliable as one might have liked (and way below the accuracy the BFI found when the rule is applied to smaller films) but certainly interesting.

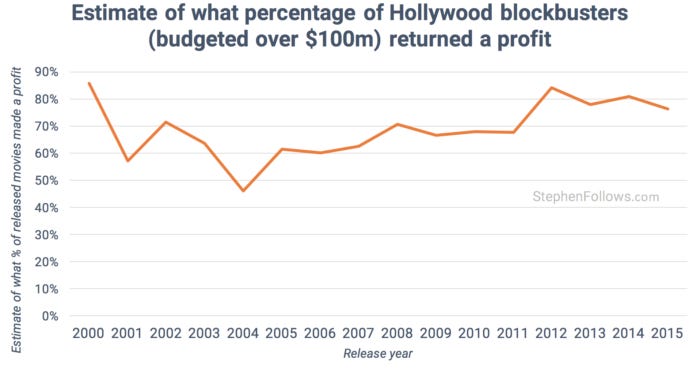

So far, I've been using a dataset of 29 movies in my investigations. But what happens if we apply this BFI rule to all $100m+ Hollywood blockbusters? I used just the published budget and box office gross to look at the 263 $100m+ movies released between 2000 and 2015.

This rule suggests that 70% of Hollywood blockbusters budgeted over $100m and released between 2000-15 were profitable. Since 2004, the percentage of movies in profit has been slowly increasing, from 46% in 2004 to 76% of those released in 2015. Most interestingly, it doesn't seem that the huge number of releases in 2011 hurt profitability.

Epilogue

So there you have it - a rather long (sorry!) look at how movies make money and why when a $100 million movie makes $100 million in cinemas it's not automatically in profit. I hope this has helped shed light on how Hollywood works and why the media's traditional view of movie profitability is frustratingly wrong.

The biggest question some readers may have at this stage is - how did he get this data? Most of the raw data for today's research is already publicly available via releases and leaks from major Hollywood studios, it's just that I have spent the time to piece it together. I was also helped by a few well-placed friends in the industry who were able to fill in the blanks and confirm the veracity of some of the data points. I also used data from IMDb, Box Office Mojo, The Numbers, Metacritic and Wikipedia.

I am completely confident that the information in this article is a true representation of how these Hollywood blockbusters make money. The reason I am being a bit cagey about exactly where the data is from is partly to protect sources/ friends but also to avoid inviting lawsuits. The purpose of this site is educational and my sole intention is to help explain how our industry works. In the past, I have been contacted by lawyers for various companies, trying to prevent the sharing of key data points relating to their business. So far, I have managed to avoid lawsuits and also to avoid having to take any articles down, but if I were to offer the full figures as a download (or details of how to do the same piecing together I have) then I suspect I would get the wrong kind of attention.

So, if you want to know any more about these movies, please add your question in the comments below. I'll do my best to answer them all, including going back to the dataset if needed.

Next week I will look at movies costing under $100 million.