In recent years, the Chinese market for Hollywood films has flourished so much that Chinese consumer demand is already affecting the content of Hollywood’s creative output. The studios can see just how lucrative China’s 1.4 billion possible cinema-goers could be, if only they can manage to stay on the right side of the autocratic and ever-controlling government. I took a look at the key numbers behind Hollywood’s new best, if temperamental, friend. In summary:

In recent years, the Chinese market for Hollywood films has flourished so much that Chinese consumer demand is already affecting the content of Hollywood’s creative output. The studios can see just how lucrative China’s 1.4 billion possible cinema-goers could be, if only they can manage to stay on the right side of the autocratic and ever-controlling government. I took a look at the key numbers behind Hollywood’s new best, if temperamental, friend. In summary:

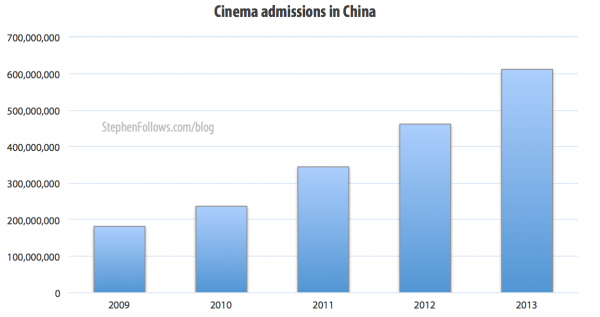

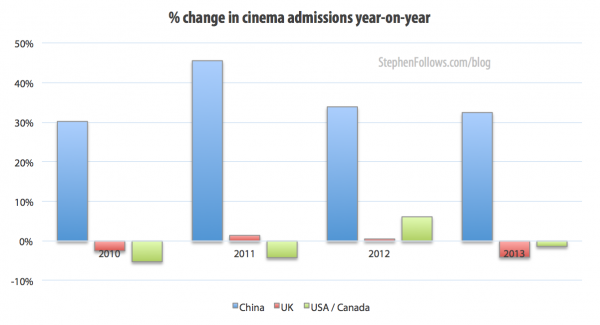

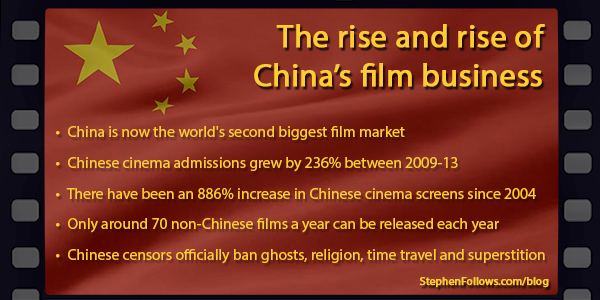

- Chinese cinema admissions grew by 236% between 2009 and 2013

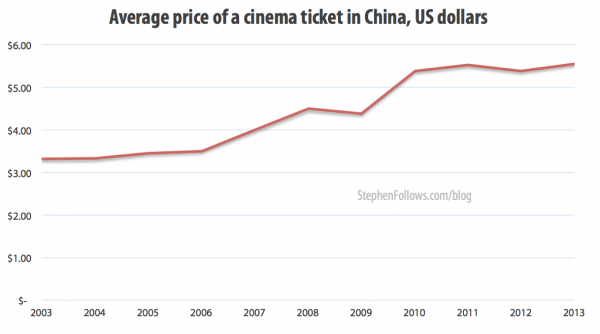

- Ticket prices are increasing, rising 26% 2009 to 2014

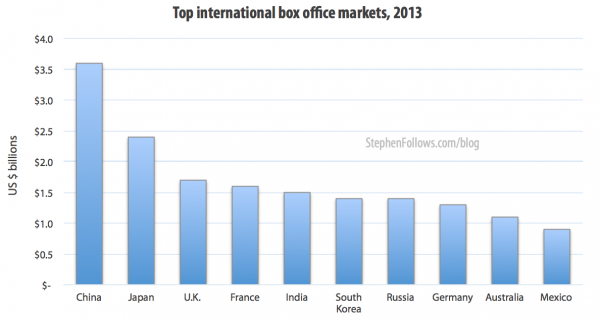

- Five years ago, China ranked 8th in the chart of top film markets

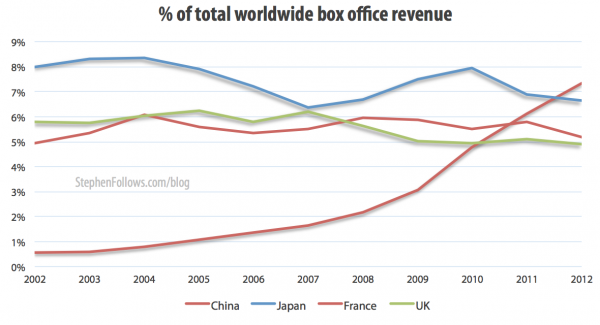

- In 2012, China overtook Japan to become the world’s second biggest film market

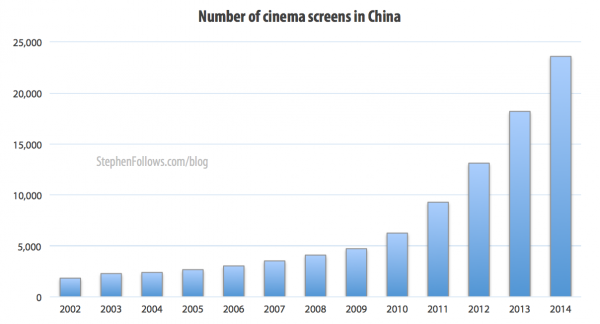

- There has been an 886% increase in Chinese cinema screens 2004 to 2014

- The Chinese State regards foreign films as propaganda, controlling with quotas

- Only 34 foreign films per year can use the lucrative revenue-sharing model

- 14 of those films must be 3D or IMAX films

- Revenue-sharing foreign films grossed $1.81 billion in 2014

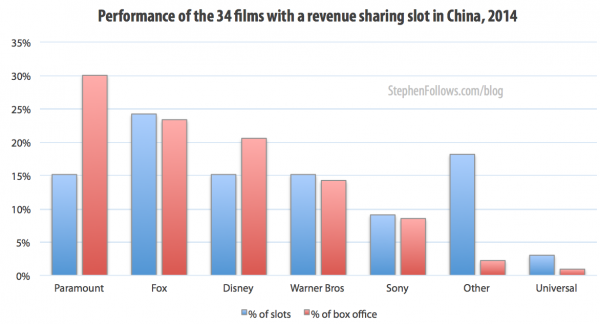

- 30% went to Paramount, who had the year’s No 1 film Transformers 4

- The Chinese censors officially ban ghosts, religion, time travel and superstition

A tale of two Chinas

The situation with regard to imported films in China is at once both very simple and quite complicated.

- The simple picture is that everything is growing at a staggering rate. A huge number of new cinemas are being built, cinema attendance is rising fast, ticket prices are increasing and more foreign films are being screened to Chinese consumers than ever before.

- The complicated picture is that the Chinese government regulates which foreign films get screened, release dates are heavily influenced by the state, censorship forces filmmakers to edit their content and a desire to please the government is making Hollywood voluntarily change their films, even those not distributed in China. Data can be hard to come by and the data that is available is often unreliable. Because of this and the visible and invisible forces at work, it’s hard to spot useful patterns.

Let’s start with the simple picture…

The good news – the film business in China is growing incredibly quickly

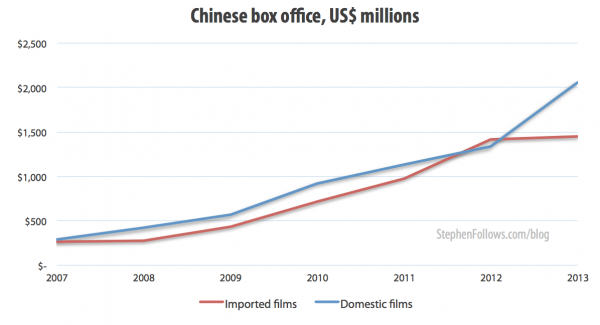

Chinese cinema admissions grew by 236% between 2009 and 2013.  By contrast, the UK and US are highly developed markets with little room for growth.

By contrast, the UK and US are highly developed markets with little room for growth.  Ticket prices are increasing, rising 26.7% 2009 to 2014.

Ticket prices are increasing, rising 26.7% 2009 to 2014.  These factors combined have meant that China is a larger and larger part of the film value chain. In 2012, China overtook Japan to become the world’s second biggest film market by box office admissions, after the USA.

These factors combined have meant that China is a larger and larger part of the film value chain. In 2012, China overtook Japan to become the world’s second biggest film market by box office admissions, after the USA.  Just five years ago, China ranked 8th in the chart of top film markets, after USA, Japan, France, UK, India, Germany and Spain (countries listed in order).

Just five years ago, China ranked 8th in the chart of top film markets, after USA, Japan, France, UK, India, Germany and Spain (countries listed in order).  The number of cinema screens in China has boomed in recent years, with an 886% increase between 2004 and 2014. Following the example of the UK cinema boom in the 1990’s, multiplexes are on the rise, with the average number of screens per cinema rising from 2.8 in 2009 to 4.5 in 2014.

The number of cinema screens in China has boomed in recent years, with an 886% increase between 2004 and 2014. Following the example of the UK cinema boom in the 1990’s, multiplexes are on the rise, with the average number of screens per cinema rising from 2.8 in 2009 to 4.5 in 2014.

The bad news – Chinese quotas on foreign films

Between 1949 and 1994, all Hollywood films were banned from Chinese release as they viewed them as propaganda (more details in the section below). In 1994 a new quota system was established, allowing 10 films to be released. There are two business models for foreign films releasing in China:

Between 1949 and 1994, all Hollywood films were banned from Chinese release as they viewed them as propaganda (more details in the section below). In 1994 a new quota system was established, allowing 10 films to be released. There are two business models for foreign films releasing in China:

- Revenue-sharing – whereby the Hollywood studios receives a percentage of the box office takings. This is the model used in almost all other countries, although in China the studio take is capped at 25% (13% pre-2012) whereas in most other countries it’s close to 50%. On top of this, the foreign filmmakers have to pay for all the marketing costs, which, in 2014, averaged 11% of the box office takings.

- Flat-fee (also known as buy-out) – A Chinese distributor will pay the filmmakers a flat fee for the rights to distribute the film in china. No other money is passed over to the filmmakers, no matter how well the film grosses.

Between 1994 and 2001, China allowed a total of 10 slots for Hollywood films using the revenue-sharing model. This was increased in 2001 to 20, and in 2012 an extra 14 slots were added for 3D and IMAX films (bringing the total revenue-sharing slots to 34). Films imported using the flat-fee model are not as carefully regulated, although it seems that their numbers tend to mirror that of the slots for revenue-sharing films, Flat-fee model films are usually smaller, independent films.

In 2012, the 34 films imported using the revenue-sharing model accounted for 45.6% of total Chinese box office, whereas the 31 flat-rate films accounted for just 5.4%. Despite the massive growth in cinema attendance and the increased quotas, imported films accounted for less of the total Chinese box office in 2013 than they did in 2007 (41.4% in 2013, as opposed to 47.5% in 2007).

Which films secured a quota spot in 2014?

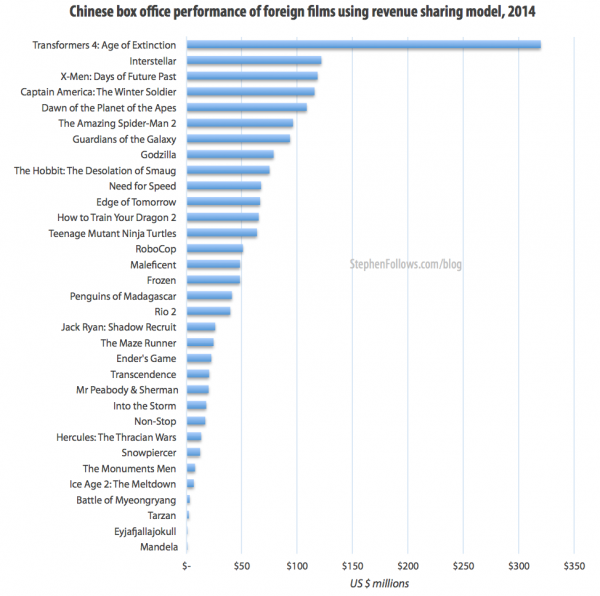

The 33 revenue-sharing foreign films released in China during 2014 grossed $1.81 billion.  30% of that figure went to Paramount, who scored a monster hit with Transformers 4: Age of Extinction.

30% of that figure went to Paramount, who scored a monster hit with Transformers 4: Age of Extinction.  N.B. One of the 2014 slots went to The Hunger Games: Mockingjay Part 1 but the film was delayed and now looks set for a February 2015 release.

N.B. One of the 2014 slots went to The Hunger Games: Mockingjay Part 1 but the film was delayed and now looks set for a February 2015 release.

Why does China have cinema quotas?

Each country’s cinema industry is a reflection of their national ideals and culture. Hollywood emerged from entrepreneurial immigrants who wanted to make money from populist entertainment. The UK industry emerged from our literary and theatre culture, although we share many cultural elements with America, not least a language. This goes some way to explaining why Hollywood is focused on making money and why the UK industry is caught between ideas of making art and wanting to copy the Americans.

Each country’s cinema industry is a reflection of their national ideals and culture. Hollywood emerged from entrepreneurial immigrants who wanted to make money from populist entertainment. The UK industry emerged from our literary and theatre culture, although we share many cultural elements with America, not least a language. This goes some way to explaining why Hollywood is focused on making money and why the UK industry is caught between ideas of making art and wanting to copy the Americans.

In China, the state has historically seen cinema as a way of safeguarding their culture and national values from creeping Westernization. And there is a no more naked illustration of extreme Western values than Hollywood films, which makes the Chinese government very worried. To put it crudely – Hollywood sees cinema as business, the UK sees it as art and China sees it as propaganda.

Before 1994 all Hollywood films were banned but now the state uses a mixture of quotas, censorship, competitive releasing and delayed releases to control which films are screened and how many people can see them. The fact that the Chinese market is opening up is a testament to the economic and political power that Hollywood can command.

The six major studios combined have a positive trade balance with all 140 countries they trade with, meaning that Hollywood can call upon the US Trade Representative to advocate on their behalf. If you’re interested in reading more about the quota system then there is a great 2013 paper by Duke University student Sabrina McCutchan called ‘Government Allocation of Import Quota Slots to US Films in China’s Cinematic Movie Market‘.

Censorship

As well as quotas, the Chinese government uses censorship to regulate what content Chinese citizens see on the big screen. In the UK and the US we’re used to ratings which provide a gradation of severity, with the most severe content being reserved for adults. This stems from the basic belief that adults should be free to view whatever they want. However, in China the censorship system focuses on the suitability of the film for the entire Chinese population.

Chinese censorship is run by the State Administration of Radio Film and Television (SARFT), who are not a fan of the following….

- Promotion of bad habits including smoking, drinking, gambling, obscenity, drug abuse, sex, violence, criminal activity, etc

- Anything not based in scientific fact including ghosts, religion, time travel, the supernatural, superstition, etc

- Criticism of anyone in power, the army, the government, Chinese culture, etc

Producer Robert Cain says: “according to the [Chinese] government, nothing bad or subversive ever happens in the modern-day communist utopia that is China. If you want to explore any salacious topics, either set them somewhere else, or in some cases, you can set them in the past”. Men in Black 3 was cut to remove all Chinese villains – not easy for a film which takes place partly in Chinatown. The cuts ended up making the film 13 minutes lighter.

Producer Robert Cain says: “according to the [Chinese] government, nothing bad or subversive ever happens in the modern-day communist utopia that is China. If you want to explore any salacious topics, either set them somewhere else, or in some cases, you can set them in the past”. Men in Black 3 was cut to remove all Chinese villains – not easy for a film which takes place partly in Chinatown. The cuts ended up making the film 13 minutes lighter.

How does this affect the content of the films?

In the late 1990’s, the Chinese government blacklisted three Hollywood studios (Disney, Sony and MGM) for creating films which criticised the China political system (namely Kundun, Seven Years in Tibet and Red Corner). In order to woo the state regulators, and therefore secure one of the all-important 34 slots, Hollywood studios have started to portray China in a much more positive light within their films.

In the late 1990’s, the Chinese government blacklisted three Hollywood studios (Disney, Sony and MGM) for creating films which criticised the China political system (namely Kundun, Seven Years in Tibet and Red Corner). In order to woo the state regulators, and therefore secure one of the all-important 34 slots, Hollywood studios have started to portray China in a much more positive light within their films.

In the remake of Red Dawn, the film was heavily delayed and finally emerged after all references to China were changed to North Korea. This was a late decision, meaning that the change had to be made in post-production, costing a reported $1 million. See here for photos from the set featuring Chinese references.

In Looper, the country in which the hero chooses to live out his blissful retirement was changed from Paris to Shanghai. The film performed incredibly well in China. This is particularly interesting as the film’s central theme of time-travel is explicitly against the SARFT’s code of practice. This may suggest that if you are able to impress the Chinese government then the censorship rules are flexible. The film grossed around $20m in China (not as much as initially reported).

The quotas only apply to foreign films and so there is a strong financial appeal for Hollywood studios to start making natively Chinese films. In 2012, Dreamworks established Oriental DreamWorks, a joint venture in which the Hollywood studios hold just 45% ownership. The remaining shareholders are state-backed private equity group China Media Capital, broadcaster Shanghai Media Group and private equity group which is owned by the Shanghai Municipal Government Shanghai Alliance Investment.

Chinese Whispers – A warning about data from the film business in China

It’s very hard to gather complete, accurate data on any aspect of China’s film industry. This is partly because of state intervention skewing numbers and also because it is a relatively new marketplace, meaning that they do not have the kinds of systems we have in place after 100 years of business in film.

Even if we get data, we cannot be sure of its reliability or what other hidden factors were at play. The Chinese government has a huge effect on film distribution, meaning that a film’s performance is much less of a marker of public interest that it is in freer, better-reported markets such as the UK and the US.

On more than one occasion, basic errors have been made on reported data. In 2012, the first week box office receipts for Looper were massively over-reported due to a mix up between US dollars and Chinese Yuan (the current exchange rate is 6.2 yuan to $1).

The data for today’s article came from Box Office Theory, the Hollywood Reporter, Entgroup, the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics, German-Films, Box Office Mojo, IHS and the MPAA.

Epilogue

I look forward to the day when film data from China is as reliable and voluminous as data from the UK and the US. I fear it may be some time off.

Comments

Very interesting. The focus seems to be on the Chinese theatrical market. Is there a home entertainment market running alongside this that is more open to films and not subject to quotas?

Damn good question. My research was around theatrical and there isn’t much reporting on home ent. I do know that DVD piracy is rift, meaning that the home ent market will be lot less lucrative for Hollywood. There is even talk about China sidestepping DVD entirely and going for a non-theatrical model based mostly on VOD. Sadly, I’m not the man to ask.

True the matters can be talked –Why does China prevent the western films coming to China.

I have studied the reasons for the prohibition for years. 2 countries try to weaken down the life of the people of China. 2 countries have plans for the worsening of the state of China. It is stupid to do damage against China. I understand Chinese leaders and why bad western films are prevented in China. Seppo Korpela Nokia Finland.

Once again, thanks Stephen, for this invaluable info. Am planning a trip to China shortly. This is really useful background for me.

Really useful and concise article, thank you. One thing I would say though is that film quotas in today’s China seem more about protecting the domestic industry than limiting the public’s access to the corrupting forces of Western ideology. Because of the proliferation of DVD piracy and the ease with which a lot of foreign content can be streamed online, the quota system can do relatively little to stop people from seeing things they want to see. The commercial logic behind giving domestic films with lower production values pride of place in the release calendar, and releasing big Hollywood films simultaneously so that their profits are cannibalised is pretty clear however!

Really interesting and useful article, thank you!

Also, Amanda, you are definitely right that there is an commercial element in the quota system but I wouldn’t underestimate the power of ideology still present in Chinese policy making. It may be that most Western films are available on the internet in China but I would say that the decision to block or allow a film on an official level is still a matter of ideology and control.

Under “The Bad News” concerning the quotas you appear to give numbers for both revenue-sharing (34) and flat-fee (31) films for 2012. Does SARFT allow 34 of each? Please clarify.

Hi Ryan

The annual quota is fixed but the exact number of films released can vary slightly. This is because slots are sometimes awarded but not taken up (changes of plans, delays in distribution mean it comes out the following year, etc).

Hope that helps

Stephen

I’m writing a paper about the foreign (foreign to the US) film industries’ responses to the American film industry and I was just wondering if you had a bibliography for all of this information?

Would love an update on this article, especially with the recent purchase by AMC/Wanda Cinema of the UCI Odeon theatre chain. This makes Wanda the biggest theatre chain in the world, correct?

Hi Stephen,

I was just curious about your ticket price information on this page, you say it rose 267.7% increase from 2009 – 2014 but the graph only shows a change from $4.3 in 2009 to $5.5 in 2013, can you clarify?

Yikes, typo! Thanks for pointing it out and I’ve fixed it