How the film industry's new shape is an amazing opportunity for filmmakers

The market has stabilised enough to act on. Here are 15 shifts over the past five years that make it easier to plan, build momentum, and maintain control as a filmmaker.

Last week, I wrote part one of a two-part series on how the film industry has changed, titled “Why the film business is considerably riskier than it used to be.”

Today I’m sharing the companion piece, focusing on all the good things about the recent shifts.

The film industry has spent the past five years operating in a fog. The pandemic caused (and exacerbated) a number of massive shifts, all of which created huge caveats and asterisks to any plans.

As we enter 2026, the fog is thinning. Not gone, and we still can’t predict the future, but we are getting more reliable signals that feel reasonable to build long-term strategic decisions on.

I’m going to go through 15 ways the film industry has changed over the past five years, and these are opportunities waiting to be taken advantage of.

We finally know what the market is

Audiences are tiring of IP and rewarding original stories

Production value isn’t chained to budget anymore

Soft money is growing and targeting indie productions

Language is no longer a barrier

Text-based AIs make small teams disproportionately powerful

Visual AI makes it easier to communicate creative ideas

The new distribution landscape rewards niche content

Audience-building is within reach of all filmmakers

Audiences want authenticity

Marketing materials are cheap enough to prototype properly

The job ladder is less rigid than it used to be

The creator economy can fuel the film economy

Global collaboration is cheap enough to be the default

Micro-studios can exist as real businesses

Let’s go through each one in turn…

1. We finally know what the market is

The past five years have been defined by moving targets. Release plans kept changing, audience behaviour kept wobbling, and the assumptions underpinning financial models failed to hold long enough to be useful.

But enough time has passed that we should recognise the market has taken on its new form.

Theatrical demand is lower than it was in the late 2010s, but it is not disappearing.

Premium formats are taking a larger share of spend.

Release windows are shorter, and audiences factor that into their choices.

Streamers are still important buyers (Netflix spent $18bn on content in 2025), but they are more selective and less willing to overpay for volume.

The practical advantage goes to people who can build natively for this reality. If your plan assumes modest theatrical, faster home availability, and fragmented discovery, you can make decisions earlier and with more confidence.

Further reading: To see the latest charts on box office, release windows and ticket prices, check out this piece.

2. Audiences are tiring of IP and rewarding original stories

We’re seeing early signs that audiences may be tiring of a narrow menu of “event” titles.

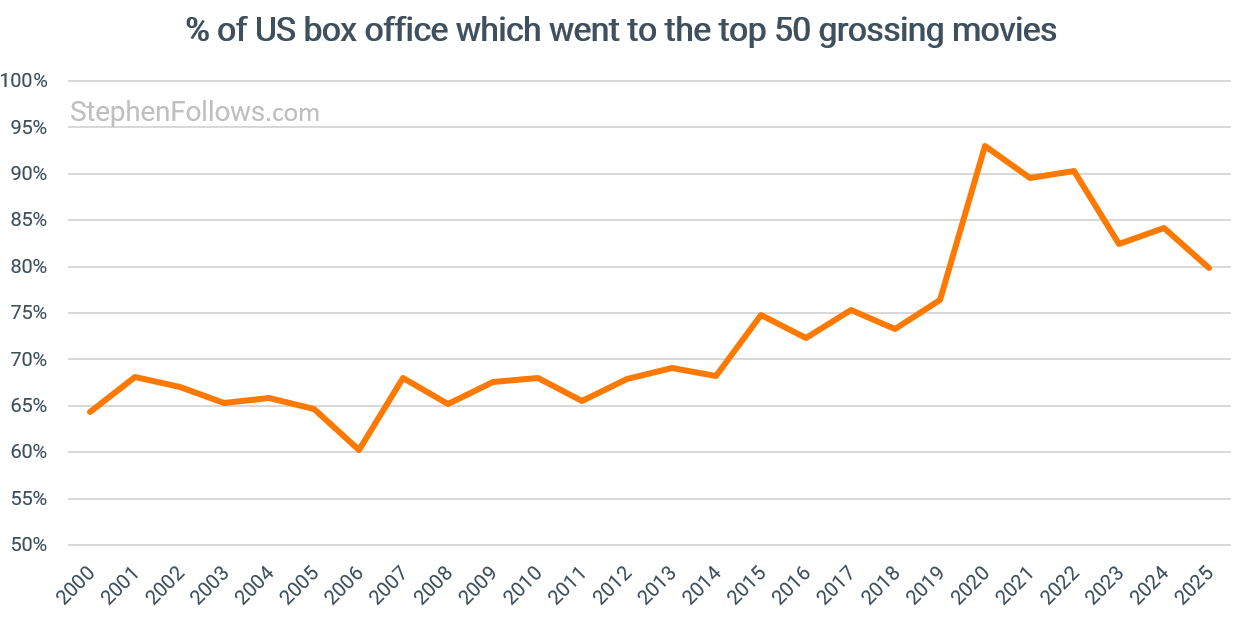

Over the past quarter-century, the theatrical market has become increasingly top-heavy, with a small number of titles taking an ever bigger slice of the pie. This was massively accelerated by the pandemic, but has started to show signs of reversing.

On the chart below, take note of the last few years and the direction of travel.

Many recent high-profile sequels and reboots have underperformed, and several large franchises have shown clear signs of diminishing returns, prompting studios to publicly cut back on volume and refocus on quality.

At the same time, a small number of distinctive films with clear positioning and strong word-of-mouth broke through the noise. Original titles like Sinners succeeded not by appealing to everyone, but by offering a clear promise to a specific audience and giving them a reason to show up and recommend it to others.

Further reading: You can see the stats on the shift towards IP-driven filmmaking at the top in an article I wrote last year, entitled Are movies becoming more derivative?

3. Production value isn’t chained to budget anymore

For most of the last century, money showed on screen. You could cut corners, you could use tricks, you could hire the right people, but there was a hard ceiling on what low budgets could convincingly pull off. Production value was a function of spend, and, crucially, was used by the industry as a key indicator of market value.

Almost every device we own captures high-resolution images. A phone, a webcam, a doorbell camera. The baseline quality of “what a camera can do” has moved up so far that image capture is no longer a meaningful differentiator for most projects.

Post-production has shifted in the same direction. Powerful editing, grading, sound, and VFX tools sit on laptops that cost less than a week’s worth of a film crew. The software is cheaper. The knowledge is more widely shared. The distance between a rough cut and a professional finish is smaller than it used to be.

Audiences have changed too. They are less fussy about texture and format, because they watch everything from everywhere, on every kind of screen. A film doesn’t need to look like a studio release to feel legitimate. It just needs to look intentional.

This doesn’t mean budgets don’t matter. They do. But the advantage of money has shifted away from creating the image and towards access. It’s now focused in:

Talent

Marketing

Distribution

These are still expensive and distinguishing market factors.

Overall, the creative playing field is wider than ever. A filmmaker can now make something visually credible on a regular budget, which changes what is worth attempting.

Further reading: Added to this, there is far less visibility on movie budgets than there used to be, further weakening the market’s previous ability to link distribution deals with production budgets. Read more on that here No-one knows how much movies cost to make anymore

4. Soft money is growing and targeting indie productions

Over the past few years, multiple territories have adjusted their tax incentives specifically to attract independent and mid-budget work, with clearer caps, thresholds, and qualification rules that are easier to model.

In the UK, the Independent Film Tax Credit now offers a 53% gross credit on qualifying spend, delivering an effective ~39.75% cash benefit after tax for films with budgets under £23.5m, claimable on the first £15m of expenditure.

Ireland followed with the Scéal uplift, raising its long-standing Section 481 incentive from 32% to 40% for feature films with qualifying spend up to €20m, certified from May 2025.

France’s TRIP remains at 30%, rising to 40% for productions spending more than €2m on VFX in France.

British Columbia increased its core production credits to 40%.

Australia increased its Location Offset to 30% for productions and lowered the qualifying spend threshold to A$20 million for films.

California more than doubled its annual allocation to $750m in July 2025, underscoring how structural incentive competition has become.

Tax incentives are more reliable than most other forms of finance and are less likely to affect the content of your movie. A budget anchored in soft money carries less downside risk, requires less speculative equity, and gives producers more control over rights.

5. Language is no longer a barrier

For a long time, language limited how far a project could travel. Even when a film worked perfectly well outside its home market, the assumption was that subtitles would narrow the audience and reduce its commercial potential.

But modern audiences routinely watch subtitled content, often without treating it as a compromise. Streaming has trained audiences to move between countries and languages as part of normal viewing.

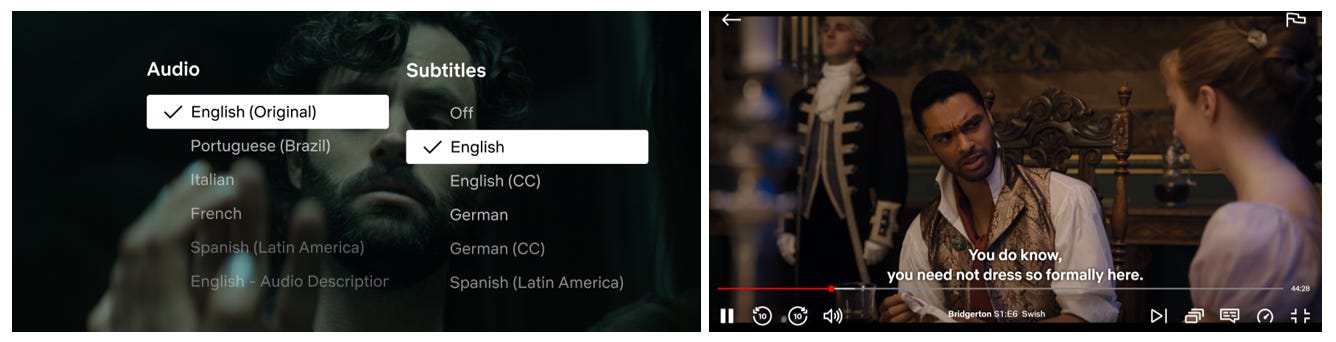

Nearly half of all viewing hours on Netflix in the US happen with subtitles or captions on. This is the highest among Gen Z, where 70% use subtitles “most of the time”.

Netflix says nearly a third of all viewing on the platform is now for non-English stories, and it offers subtitles in 33 languages and dubbing in 36.

97% of US subscribers watched at least one non-English title in a year.

In major English-speaking markets, 54% of consumers said in 2024 they watch non-English content “very often” or “sometimes”, up from 43% in 2020.

96% of Gen Z prefer subtitles over dubbing - the cheaper of the two options, which must be a relief to cash-strapped filmmakers!

The practical effect is that stories can remain culturally specific and still travel. A film does not need to be remade, recast, or flattened to reach other territories. The distribution logic shifts from “will they watch subtitles?” to “will the right people find it?”

Localisation has changed too. Subtitling and dubbing are faster and cheaper than they used to be, and AI-assisted tools have reduced the friction of preparing multiple language versions. That does not remove the need for human judgment or proper QC, but it makes global distribution less intimidating for smaller teams.

For filmmakers, this expands the addressable market without requiring a change in the story itself. A film can be made for one place and still have a realistic shot at audiences elsewhere, because language has stopped being the automatic limiter it once was.

6. Text-based AIs make small teams disproportionately powerful

A lot of film work is admin. I mean, a crazy amount. So much so that the paperwork and administration overhead is one of the major reasons I hear first-time filmmakers cite for not wanting to make a second.

It is emails, schedules, revisions, contracts, call sheets, submissions, deliverables, translations, grant applications, briefing documents, meeting notes, cover letters, NDAs, chain-of-title summaries, deck updates, and endless versions of the same paragraph written for different people.

That work used to scale with headcount. If you wanted to operate like a proper company, you needed a company and a team.

In 2026, you can cover a large chunk of that workload with text-based AI. Not perfectly, but fast enough to change what a small team can realistically attempt.

You can draft outreach in minutes and tailor it for a buyer, a sales agent, a brand partner, or a festival programmer without rewriting from scratch each time.

You can translate messages into other languages quickly enough that international conversations stop being a specialist task.

You can record a meeting, focus on the conversation, and be confident that you will have neat notes and agreed-upon action points at the end.

You can turn a scrappy set of notes written over months into a coherent document that someone else can act on.

For better or for worse, we still need lawyers. But you can use AI to read a contract, highlight unusual clauses, explain terminology, and compare it to your previous agreements. That changes how quickly you can spot problems and how confidently you can ask informed questions.

The net effect is that the minimum viable size of a professional operation has shrunk.

AI does not remove the hard parts of filmmaking, but it makes the surrounding machinery lighter, which is exactly where many emerging filmmakers get stuck.