Why the film business is considerably riskier than it used to be

From cinema habits to corporate consolidation, a decade of structural shifts has made film success harder to achieve and harder to measure.

This is part one of a two-part deep dive into how the film industry is changing. This one focuses on the adverse effects, with the follow-up next week focusing on the positives. So strap in, this is not going to be a cheery read.

The film industry has always been risky, but in recent years, those levels of risk (and the deleterious attempts to mitigate them) have made it much worse.

The underlying mechanics have shifted in ways that make it harder to finance films, harder to market them, and harder to predict what success even looks like.

In this article, I go through eleven structural changes reshaping the business, including:

Cinema-going may never return to pre-pandemic levels.

Cinema trips are shifting from routine to a treat.

Consumers have been trained to expect short windows.

The business model has become harder to see.

Corporate games mean instability for everyone.

International markets are no longer a dependable safety net.

Generative AI has moved from theory to real threat.

Marketing has become harder, faster, and less predictable.

Market instability is leading to creative cowardice.

VFX remains one of the most fragile parts of the film supply chain.

Other forms of filmed entertainment are still growing.

Let’s look at each in turn…

1. Cinema-going may never return to pre-pandemic levels

It’s coming up to six years since the COVID-19 pandemic devastated the global film marketplace. Films couldn’t be shot, cinemas couldn’t open, and audiences were worried about being in public spaces. While medically the world has bounced back from COVID-19, the theatrical film sector has not.

The industry is starting to grapple with the notion that we’re not ‘bouncing back’, but instead are seeing a new normal.

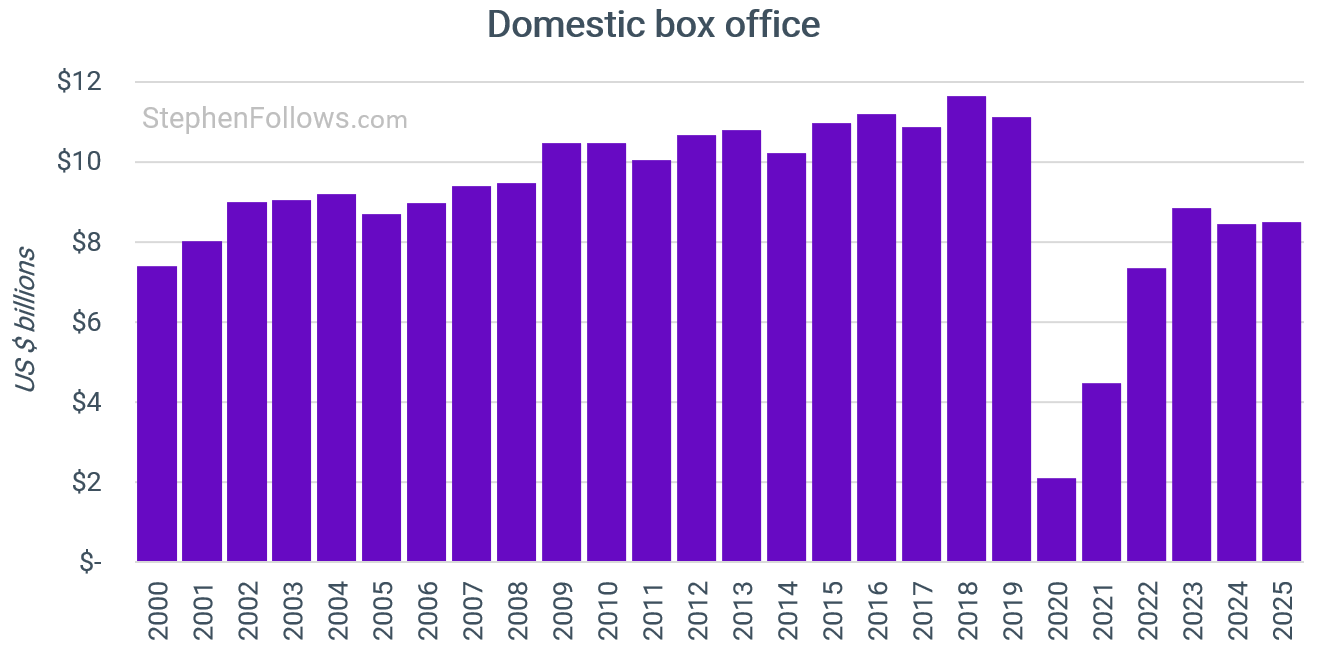

The 2025 domestic box office ended the year well below the late-2010s highs, despite multiple major releases.

And this is a pattern we’ve seen worldwide.

As far as I can tell, the only countries in which the 2025 box office matched that of 2019 were still-maturing markets, such as the United Arab Emirates.

2. Cinema trips are shifting from routine to a treat

The pandemic, the rise of streaming, and the massive increase in the cost of living have reframed cinema-going in people’s minds. Rather than a low-friction, cheap night out, it has moved into the category of a ‘big night out’, such as big music gigs or theatre.

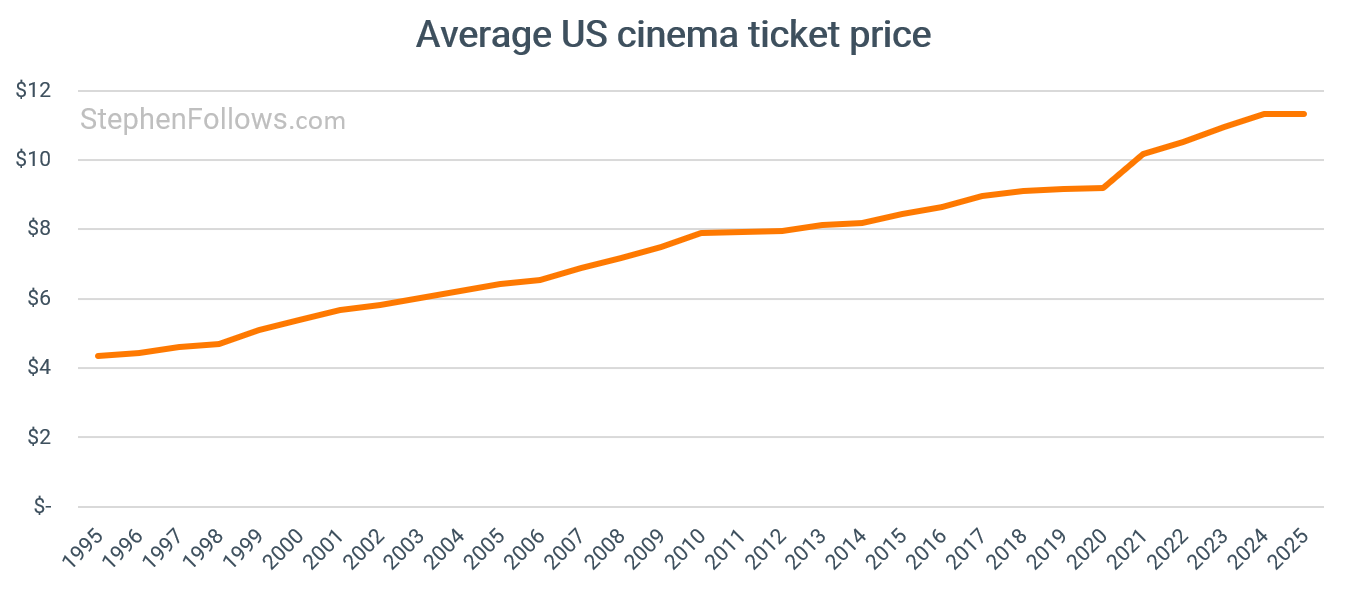

The average cost of going to the cinema has risen significantly, right at a time when people are feeling the pinch from rising prices elsewhere.

Further reading: I wrote about this in detail a few months ago, taking in data from around the world. The cost of the trip to the cinema is the number one barrier to increased cinema attendance in almost all cases.

The cinemas have responded by trying to increase the value of a trip to the cinema - better seats, more food options, etc.

Recliner seats, pods, beds and bundled food have pushed the typical spend per visit higher, even when base tickets remain available. Vue’s premium seats now top out at around £26, and Odeon’s VIP beds reach £35 for three.

The issue is that they need to recoup these investments, so they are forced to increase yield per customer, feeding the symbiotic loop, which increasingly pushes up the price of cinema-going even more.

Once cinema becomes a “treat”, it stops behaving like a habit. And habits are what sustain mid-budget films, long theatrical runs, and repeat viewings.

3. Consumers have been trained to expect short windows

Cinema audiences now build “when can I watch this at home?” into the decision to buy a ticket.

A recent Cineworld/Regal consumer survey found that a third of consumers believe that a film will be available to stream at home within 30 days of release.

I’m currently working on a longer deep dive focused on release windows, but I can share that consumers’ assumptions are pretty spot-on. Over the past few years, the average movie has moved from US cinemas to US homes in around 37 days. Half of what it was pre-pandemic and a sixth of the figure in the early 2000s.

It’s arguable whether this is a good or bad thing. Indeed, it helps streamers and hurts cinemas, but its overall effect on both consumers and filmmakers is less clear.

A recent report on European release windows recommended prioritising theatrical exclusivity, arguing that it remains the most profitable window, and suggested shorter windows should be used selectively for niche titles. It also concluded that routine day-and-date releases undermine both cinema and downstream revenues.

Similarly, The Numbers concluded that “short theatrical windows cost domestic theatres about $100 million a year”.

4. The business model has become harder to see

In the old system, films were still risky, but the economics were at least legible. Box office was the key metric (and a public one at that), plus the secondary markets were clearer and published some data. A film’s performance was more directly tied to its own results, across a sequence of windows that created multiple chances to recoup.

The increasing importance of streaming in the value chain has eroded this clarity. As more viewing shifts to streaming, more performance data sits on private platforms rather than in public reporting. Even advertisers are now pushing for basic transparency standards in streaming, because the market still lacks consistent measurement and accountability.

This makes it increasingly challenging to model demand when comparable performance data is unavailable and success is increasingly measured behind closed doors.

The deal structures have shifted too. Buyout contracts are now standard in the streaming era, replacing the older residual-based model and reducing the link between long-term audience performance and long-term earnings.

A recent report from the University of York, entitled Screenwriters’ Earnings in the Video Streaming Age, concluded that there was an “almost universal experience of buyout contracts” for SVODs, and that in a typical buyout, the production company purchases the work, so the writer receives no future payments in the form of residuals.

When platforms purchase worldwide exclusive rights, the upside is capped. You may secure certainty upfront, but you’re also giving away the possibility of a runaway hit that grows over time across markets and windows.

Finally, the palpable reduction in the quality of mainstream film trade journalism hurts filmmakers and film professionals alike. Fewer journalists, tighter deadlines, and thinner margins have all conspired to reduce the availability of high-quality research to the industry.

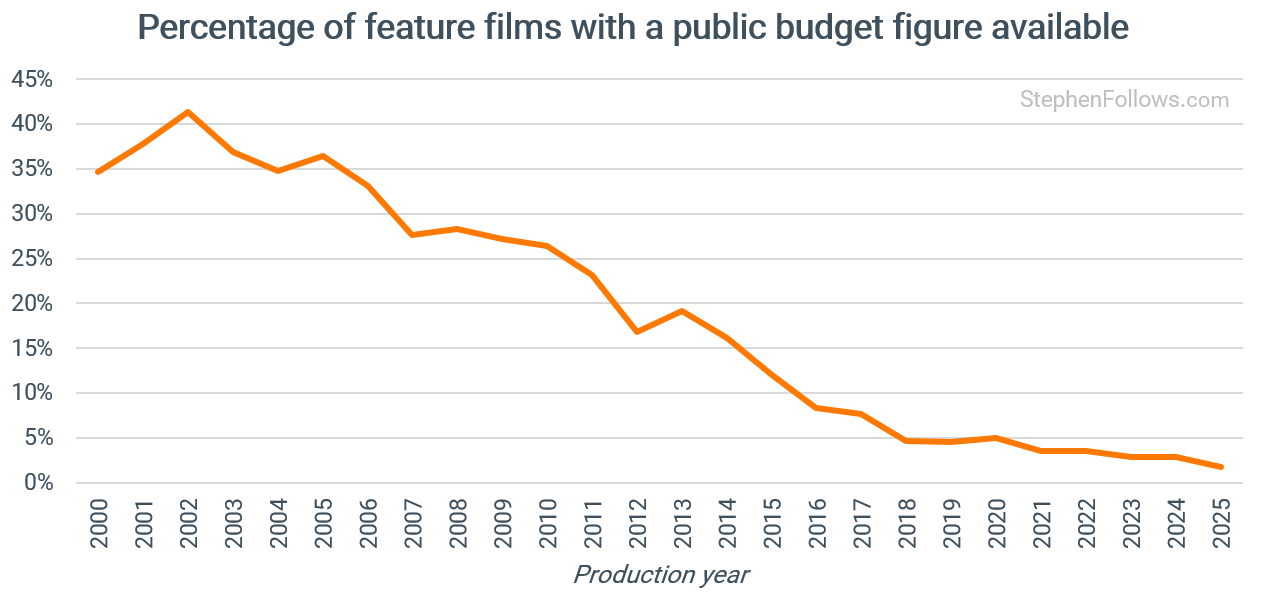

This can be seen in the research required to understand a simple cost - how much a movie costs to make.

Further reading: I looked at the topic of poor budget reporting a few weeks ago in an article entitled No-one knows how much movies cost to make anymore