What do film critics think of film festival standing ovations?

I analysed 1,941 trade press articles and spoke to leading critics to uncover whether standing ovations actually mean anything.

When I published my first piece on standing ovations at film festivals a few weeks ago, I expected it to be a niche topic.

Tricia Tuttle, the director of the Berlinale, had asked whether applause length meant anything, so I looked into it. The data revealed that standing ovations at major film festivals are becoming far more prevalent, but that there is no meaningful correlation between the length of applause and a film’s later success.

What I did not expect was the reaction that followed.

The article was widely read and shared, and many people reached out to share their point of view. This included being invited to be interviewed by Matthew Belloni on his podcast The Town.

The episode is worth a listen as standing ovations are a point of particular interest for Matthew. He opened with:

I find it absolutely ridiculous that these ovations, which are driven by such disparate reasons…all of it produces these articles that appear at festivals. And people think that because the ovation is 15 minutes, that it’s actually a good movie.

He blamed the trade press, but also spared some disdain for the festivals:

The film festivals are complicit here. They like it because they need the stars to be in the room… If the ovation is going to be larger with the star in the room, then by all means measure the ovations because that gives the incentive for the star to be there.

Matthew’s questions prompted me to look deeper at how they are covered and interpreted by the trade press and professional film critics.

I looked at almost 2,000 articles and reached out to a number of top critics to understand more about what standing ovations mean.

How crucial are standing ovations for securing news coverage?

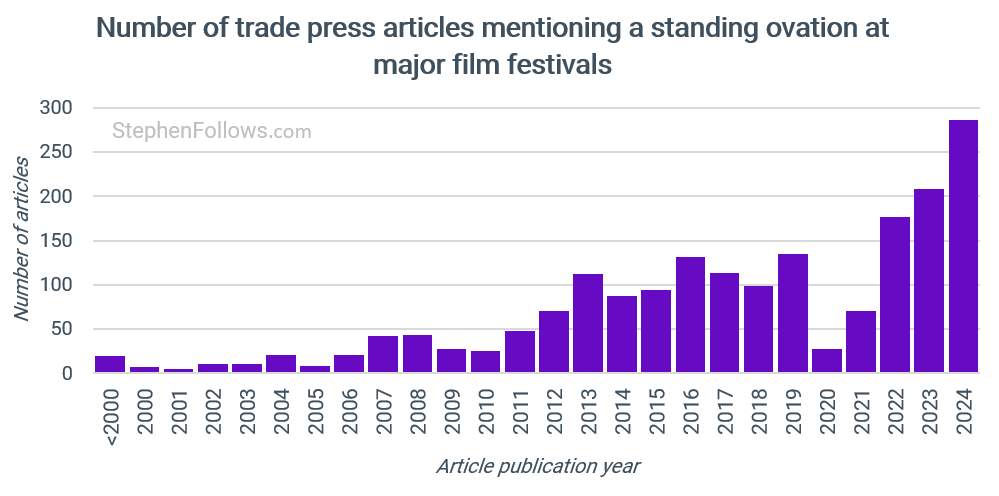

Let’s start with the film trade press. I collected 1,941 articles from Deadline, Variety and The Hollywood Reporter that mention standing ovations at one of the five major film festivals (Cannes, Venice, Berlin, Toronto and Sundance) over the past quarter century.

The results reflect the same pattern we saw last time, namely a sharp increase in coverage for ovations in recent years.

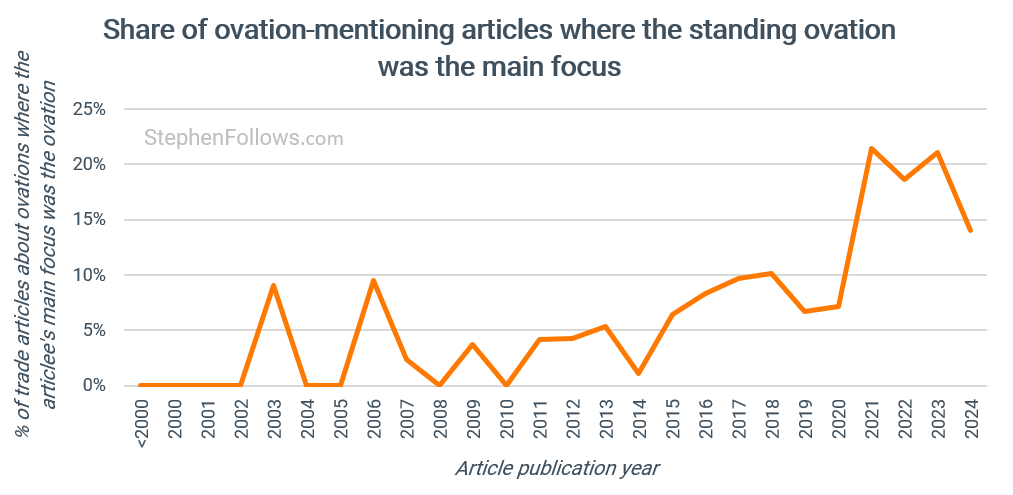

I classified each article to determine whether the standing ovation was a passing detail or the main reason the piece existed. This matters as if it’s the latter then we could say that the ovation had effectively generated new coverage for the film. Without the clapping, that article would not have been written.

This means that the clapping has created over 200 new articles that wouldn’t otherwise have been published.

Trade journalists have always relied on shorthand signals to convey industry consensus (i.e. box office, reviews, deals, awards buzz, etc) and the standing ovation has loudly joined that list.

How are the ovations framed?

Not every mention of a standing ovation becomes the story itself. Many appear as part of wider festival coverage, providing colour, validation or contrast.

Across the articles which were not solely about the ovation but do mention it, I found six common framings. They are descriptive rather than mutually exclusive, in which several pieces blend more than one.

1. Stopwatch PR (the “duration leaderboard”)

This is the most common form and arguably the one most associated with Cannes and Venice. These articles treat the ovation as a measurable achievement, complete with minute counts, rankings and festival records.

The implicit logic is that longer applause equals stronger approval. Reports often include side-by-side comparisons with previous films or note when a movie “beats” or “falls short” of another’s time. The language mirrors sports coverage with words like “clocked,” “timed,” and “longest so far” appearing repeatedly.

If anyone wants to join in with commentary on ovations in this way, they would be wise to take note of the differing methodology each outlet uses to define their report time, as shown in the previous research.

2. Tear-jerker reception (emotion as story)

This framing was all about human reaction and emotion, with the coverage focusing on the tears, hugs, relief, and catharsis. This mirrors the social media images and videos of actors crying or embracing that circulate widely which thereby converts the private ovation into a publicly shared emotional event.

Coverage of Brendan Fraser at The Whale is the most cited example, but similar moments recur with Harrison Ford (Indiana Jones), Dwayne Johnson (The Smashing Machine), Lily Gladstone (Killers of the Flower Moon) and Elton John (Rocketman).

3. Awards bellwether (the “Oscar launch” read)

For trade writers covering festival season, awards potential is a near-default lens. In this mode, the ovation becomes evidence that a film is entering the awards conversation.

References to “Oscar buzz,” “frontrunners,” and “launchpads” appear frequently. The articles connect present reactions to past campaigns such as The Shape of Water, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, Roma, Tar, to suggest a link between festival ovations and later nominations. I have already shown that this is not true, statistically speaking.

4. Market and deal framing (sales leverage)

Another framing ties the applause directly to the business side of the industry. In these pieces, the ovation signals buying interest, presales momentum or valuation strength. Phrases like “buyer frenzy” and “competitive bidding” often appear in the same paragraph as the length of applause.

This framing tends to dominate Sundance and Cannes reports, where acquisition activity is most visible. It treats the ovation less as artistic endorsement and more as marketing collateral. A seven-minute standing ovation can be positioned as evidence that the film “played well in the room”.

5. Spin cycle (countering boos or controversy)

Some of the most revealing articles use the ovation to reframe negative press. If a film receives boos at a morning press screening, its evening gala can be written up as redemption. Examples include Personal Shopper, Sea of Trees and Jeanne du Barry, where the narrative shifts from rejection to vindication within hours.

This juxtaposition between the ovation and the write-up is felt in other ways, too. When interviewed by Variety about the reception Pixar’s Elemental received in Cannes, Pete Doctor highlighted how out of step the ovation was was with the reviews released moments later:

Variety: Did you look at the reviews from Cannes?

Pete Doctor: That was a confusing half-hour there. The film played, we got a seven-minute standing ovation, and you could feel the love beaming down from the audience to Pete [Sohn, the film’s director]. They really responded to it. Then the embargo lifted and some of the reviews were pretty nasty.

6. Meta-ovation discourse (self-aware or sceptical pieces)

Finally, a smaller but growing strand of writing acknowledges the absurdity of the whole practice. These pieces critique the timing of ovations, question their significance, or suggest that nearly every gala receives one.

The Hollywood Reporter even published a call for a “cease-fire” on stopwatch coverage under the great headline:

Standing Ovations Are Getting Ridiculous. Who’s to Blame? (Okay, It’s Us).

During our chat on the On The Town podcast, Matthew Belloni was very open about his role while being Editorial Director of a major trade publication:

During my time running The Hollywood Reporter, I am complicit in this. I presided over the outlet that was doing this…because it got picked up. You’re looking for traffic and if you can say, ‘Controversial Cannes movie got a 20-minute standing ovation,’ all the aggregators would pick it up. That’s where this started.”

This brings us neatly onto the second type of follow-up research I conducted on the topic…

Critical critics criticism ovations

I reached out to a number of professional film critics to ask them what they thought of standing ovations at film festivals. Some spoke ‘on the record’ while others wanted to remain anonymous or only ‘on background’. All are Rotten Tomatoes–approved writers, many with decades of experience covering major festivals.

The consistent view I heard was that standing ovations are just theatre, rather than anything meaningful.

Little White Lies editor David Jenkins called the entire concept hollow:

[Standing ovations are a] completely artificial metric used to fill out pages of film trade publications and as bait for social media.

and when asked if they signify anything, he said:

They signify people’s capacity to be polite to celebrities presenting their art to the world.

Many pointed out the insular nature of the people taking part. James Berardinelli put it like this:

My perspective has always been along the lines of “what happens at film festivals stays at film festivals.” It’s a rarefied atmosphere with everything happening in a bubble. I can recall countless festival darlings that have vanished without a trace. (”Happy Texas” ring a bell?) People who attend festivals are die-hards (or, in some cases, politicians who want to be seen) and bear little resemblance to “regular” audiences. The gap has widened considerably post-pandemic.

Similarly, Peter Sobczynski described them as “performative gestures” rather than genuine reactions.

I think most of these standing ovations—particularly the elongated one breathlessly reported in the trades and online—are a bit silly and mostly a performative gesture towards the big stars sitting in the auditorium than anything else. For the most part, they are just noise and now that people are reporting on them as if they actually mean something, people do them because they think they are expected to now.

Mike McCahill described standing ovations as “one of the many absurd elements of the modern film festival experience.” He added:

I’m sure a small number of them are genuine, organic responses to great filmmaking, but many many more strike me as a mechanism contrived to flatter those creatives who’ve agreed to attend while also eliciting the maximum number of column inches. And in no way a reliable guide as to the quality of the film being cheered.

A self-sustaining cycle

Several critics noted the circular relationship between coverage and behaviour, such as John Bleasdale:

The reporting of applause has become silly and counterproductive but I know that these articles are clicked on. So readers say they don’t want them but click on them. Journalists know they’re silly but they get traffic.

And audiences know someone has a stopwatch even as they applaud and their hands sting.

A critic who wished to stay anonymous evoked the metaphor of a snake eating its own tail:

I‘m of the opinion that standing ovations at film festivals are a bit of an ouroboros where the reporting on the ovations encourages film teams to orchestrate longer and longer ovations for the sake of headlines, and so on.

Marshall Shaffer feels they did once have value but that the proliferation and reporting has undermined that.

I think of them as a once-useful tool for gauging audience sentiment out of big premiere screenings. However, they have now become a cynically deployed tool of PR launches used to game headlines that a cottage industry of “stopwatch journalism” has been all too happy to accommodate.

It’s all about the mood, not the art

For Helen O’Hara, standing ovations may capture the mood of a moment but not artistic value.

I think they’re pretty much irrelevant except as, at most, an expression of some sort of Zeitgeist. They can reflect the general popularity of a filmmaker or actor, or a general sense that the subject is important or worthy, as much as expressing enthusiasm for the quality of the filmmaking per se.

She also sharply observed that who’s in the room will affect the ovation intensity:

The presence of a major A-list star can affect the length of the ovation, I suspect. Those attempting to draw significance from a 10-minute as opposed to 15-minute ovation are, I would respectfully suggest, on a hiding to nothing

As a side note, I personally remember seeing premieres at the London Film Festival during the actors strike and the lack of big name talent in the room cooling the film’s reception.

Not a useful measure

A nameless critic said:

Every ovation carries its own set of variables, such as who’s in the room, what the film represents, how late in the day it’s playing, or whether the publicist is gently encouraging more applause. None of these factors can be standardised, which makes comparing durations meaningless.

Not every critic dismissed the practice entirely. John Bleasdale recalled instances where applause did feel authentic.

I’ve been in rooms where the applause has been a genuine emotional response and is kind of a reward for the filmmaker. The Voice of Hind Rajab for instance in Venice recently.

Do standing ovations affect the critic’s view?

Interestingly, most were open to the idea that an extended standing ovation is likely to lift their opinion of a movie, albeit only marginally. Marshall Shaffer said:

I’d be lying if I said they did not somewhat enter into my calculus, but they rank far below things like actual critical reviews or audience sentiment expressed on social media. I usually write off a short standing ovation, but a long standing ovation is likely to build the hype in my mind -- and likely set it up to underwhelm me.

A critic who requested to remain nameless said:

No one likes to admit it, but critics are human. When a room’s vibrating with applause, that buzz seeps in. For a moment, even the most jaded writer wonders if maybe they missed something everyone else saw.

Another said:

It’s hard to stay entirely immune to the energy of the room. A long ovation can create a sense of shared enthusiasm that lingers.

We’ll end on this anonymous scribe’s view:

At this point, I assume anything under 10 minutes means the audience didn’t like it. I remember reading that Beetlejuice 2 got a 3-minute ovation and thinking, “ouch.”

Further moaning reading

Finally, if you still haven’t got enough of people complaining about standing ovations, here are some choice essays you may enjoy:

Measuring ovations is deeply silly’: what’s behind the rise of the standing ovation story? Screen Daily argues that the gesture has become so common it has lost its impact and is not a reliable metric for film buyers or marketers.

Are standing ovations at film festivals getting out of hand? by Guy Lodge in The Guardian argues that standing ovations have evolved into a “publicity game” and a “clickbaity” metric that ultimately means “nothing at all regarding a film’s long-term prospects”.

When the Applause Just Won’t End by Shirley Li in The Atlantic, in which she calls them “awkward”. She spoke to a professor at the University of Michigan who said “It’s fun to kind of watch them as a sociological exercise”.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Have you seen Luke Barnett & Noam Kroll's Short called "Ovation"?

https://youtu.be/ZA_xugUCw6o?si=3yweFuIEhhm5rQWg

https://variety.com/2025/film/global/joaquin-phoenix-reaction-cannes-ovation-short-film-1236537184/

I love a rigorous data-science analysis of press trends!! Well done! One other angle to explore: Does the Penske monopoly of the trades have any correlation or relevance here? Just wondering. (And maybe you’ve explored earlier) If any correlation between ovation length and running time of movie? Also, correlation with start time?? (Ie 7pm shows have longer/shorter ovations than 9pm shows).