Why are modern films framing actors’ faces differently than they used to?

Using data from over 3,655 movies, I've discovered that directors are increasingly framing their character shots differently.

Films evolve in many small ways that are easy to miss if you are not looking for them.

One area I had not studied before is shot composition. It is such a basic building block of visual storytelling that any change could indicate something interesting about how modern films are made.

So I have started my journey by looking at shots which feature faces, and I have found something rather intriguing.

I built a library of 3,655 live-action, fiction feature films, detected when shots changed, and looked for faces in each shot.

By dividing the height of the face by the height of the frame, we generate a simple ratio - that of face size as a proportion of the frame. A higher value indicates the camera is physically (or optically) closer to the face, whereas a lower value indicates it is farther away.

How often do faces appear on screen?

Before looking at how close films get to actors’ faces, it helps to see how often faces appear at all. Across films released since 2000, there are apparent genre differences in the share of shots that contain at least one detectable face.

Horror, sci-fi and adventure films show the fewest face shots, with just under half of their shots featuring a detectable human face. These tend to be movies featuring large environments, action sequences or visual effects, which naturally produce more shots without people in the foreground.

At the other end of the spectrum, we have more “human” genres, such as comedy, romance and music-based movies. Nearly two-thirds of shots in these movies have faces.

Another way of understanding this is to consider the extent to which the narratives are driven by dialogue. While I wasn’t measuring whether the faces were talking, it’s a fair assumption that movies that require us to watch people talking will feature more close-ups of faces.

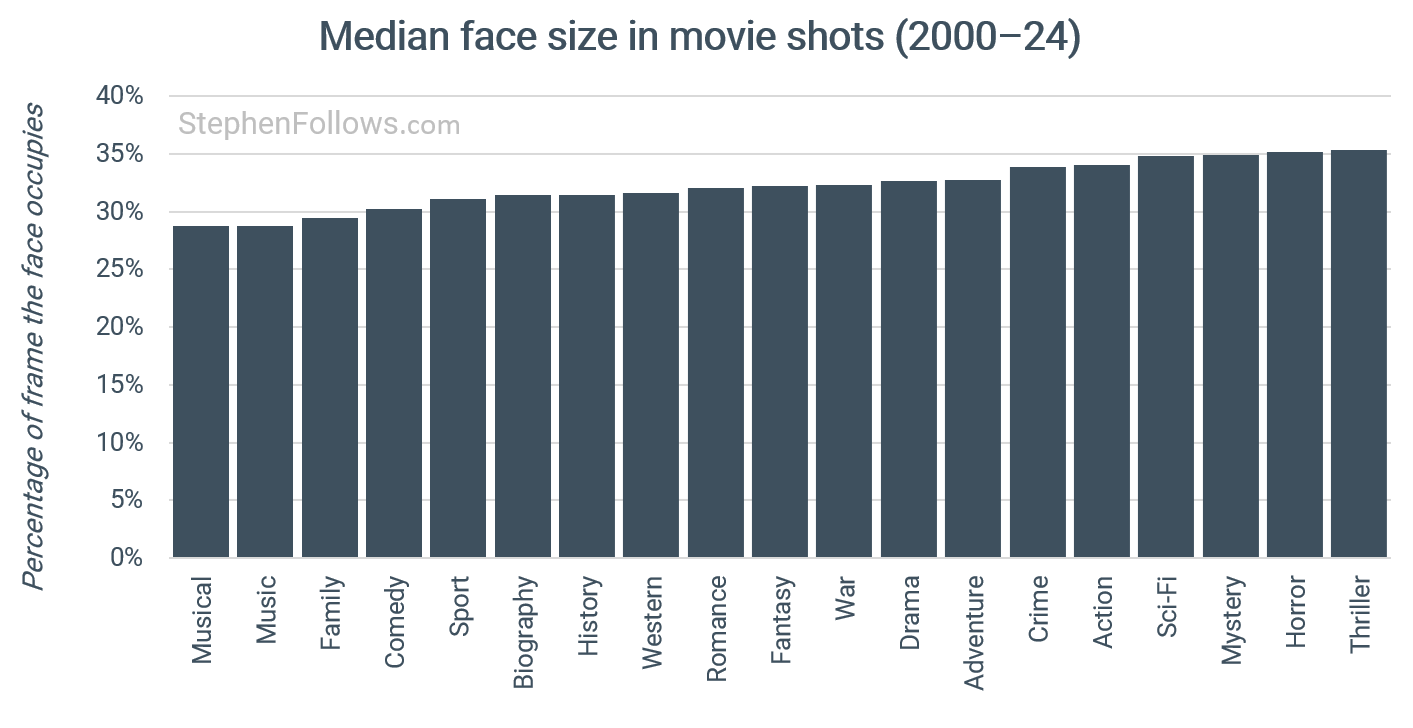

How tightly do genres frame their characters?

Now that we know where the faces are, we can look at their size. Interestingly, we see the same clustering as above, but in the opposite order.

I.e. while comedies and musicals show the most significant number of faces, they also show us the smaller faces. This is in large part due to the desire to have more than one person in the frame at any moment.

Mysteries, horror films and thrillers have the largest average face size, presumably forcing us to take in the extreme reactions and psychological tension written across the faces of the character(s).

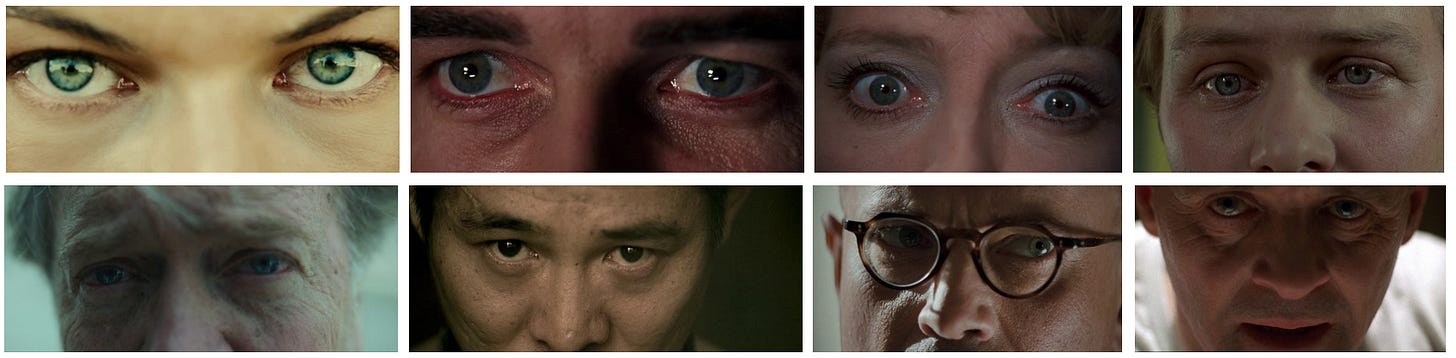

The same pattern is starker when we zero in only on extreme close-ups. I grouped all the face shots into one of four buckets, defining an extreme close-up as one in which the face is at least 50% of the frame’s height.

Nearly a quarter of all shots of faces in thrillers are extreme close-ups, compared with about one in ten for family movies.

Now that we have our bearings on what we’re tracking, I can turn to the headline mystery.

How face size has changed over time

By looking at the release year of each film, we can build a picture over time. Doing this shows that, during the 20th century, faces got bigger. I have patchy data on movies from the first half of the century, but the data suggest an average face size of under 20% of the frame height.

The data is richer from the 1980s (hence the chart below, which starts in 1980), by which point faces occupied an average of 30.2% of the frame.

The peak was in the 2000s, when faces grew to 34.1%, after which they began to fall again. Of the films I studied from the current decade, the average fell to 29.7%.

Initially, I thought this might be down to changes in the types of films being made. In past research, I have shown how romance has dropped from 34.8% of movies in 2000 to just 8.6% in the 2020s, and horror has more than doubled over the same period.

But when I split the data by genre, the pattern remains, universal across genres.

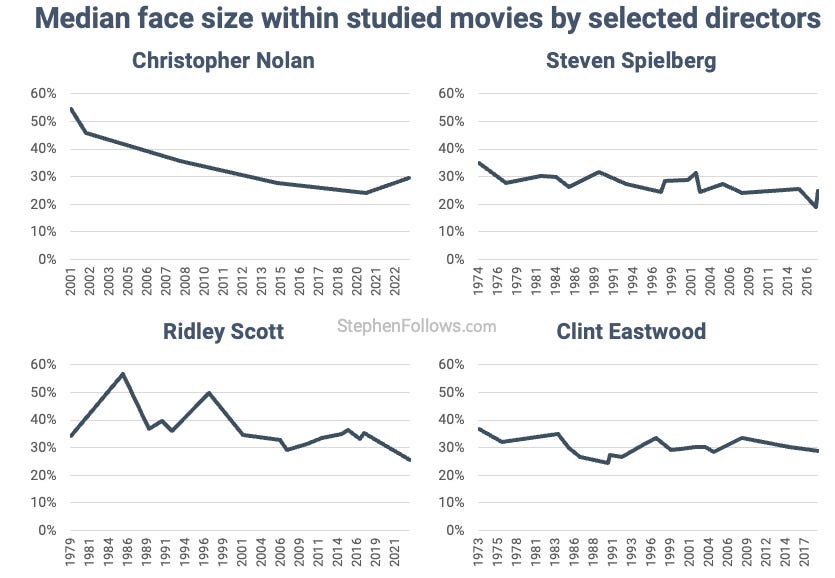

It’s happening across directors, too. The majority of directors have seen a reduction in their average face size. Below are just a few examples I’ve chosen to make the point.

Why is this happening?

The data shows a clear shift in how close films place the camera to actors’ faces, but it cannot tell us why.

A few possible suggestions from me (i.e. neither a director nor a cinematographer):

Digital cameras allow filmmakers to shoot clean images in low light without placing actors near strong key lights. This makes it easier to work with wider shots in situations where older equipment produced noise or inconsistent exposure.

The rise in large-scale sets, digital environments and complex action work may encourage broader framing, because more of the world needs to be visible.

LED volumes or virtual environments can simplify lighting and speed up filming. Still, they often produce soft, even illumination that is easier to work with when the camera is further back.

Changes in production schedules may favour efficiency, and wider setups can be quicker to relight or repeat.

How we watch filmed content has changed over this period. Most people have a considerably larger television screen than they did in the 2000s. But at the same time, there is a broader use of tiny screens, often watched in more varied environments (i.e. on the bus, on mobile, etc)

The blurring of “Films” and “Television” that the streaming era has created, due to the proliferation of big-budget streaming series.

But overall… I don’t really know.

What do you think? All comments and suggestions are welcome in the comments below.

Notes

For this research, I built a dataset of 3,655 live-action, fiction feature films. For each, I detected individual shots, extracted keyframes, identified human faces and measured the boundaries and location of the face(s). Across the 3,655 films, this resulted in several million stills.

The height of this face was divided by the full-frame height to obtain the face size ratio.

The article’s genre-level comparisons use only films released between 2000 and 2024. This produces a consistent modern sample and avoids mixing older and newer production styles. When looking at long-term trends, earlier films were included, but only for the year-by-year face size chart.

My dataset does not include every film made, so there will be some gaps (including for the body of a director’s work). Nonetheless, I don’t feel this is skewing the results.

Your well researched, data driven articles always deliver fascinating content. Thanks for stimulating my brain cells once again. Some of your posits for reasons why are nonstarters because they don't stretch through the entire timescale of your data showing the effect. Digital cameras have been affecting the look of cinema for less than 20 years, so joined a trend, if at all, already in progress. Same for volume LED screen producions which only have been impactful for merely five years or so.

One potential contributing factor could be lens developments over the decades. Early era lenses had a look and styling of the image because of their limitations of costruction and coatings resulting in lower light level available. An average apeture of T5.6 or darker was common. This meant that a close-up of a face would naturally retain focus on the entire face. Lens maufactoring has brightened the availability of lens offerings significantly over your time period. This not only allows filmmaking in environments with much less lighting needed but also changes the look of those same close ups. A modern T1.2 or at the extreme T0.95 lens has an extremely shallow depth of field when wide open. That DOF would make a close up of a face that was in full focus with older lenses need to choose between having only the eyes in focus with a quick fall off of focus with the rest of the face, (blurry nose, ears, etc.) If that effect isn't the desired effect for the scene, the quick fix without relighting or changing apeture to stop down, is to back the camera away from the subject, thus placing more of the face within the sweet spot of narrow focus.

This might not even be a conscious chooice, but a matter of adopting to the equipment and prodution needs of the day. Meaning, we're getting smaller faced close ups as a biproduct of having too good lens options. Just a theory. Love all that you write, keep at it!

One thing you mentioned that might bear further scrutiny is how the recent reduction in face size might correlate with a reduction in amount of dialogue in those films. Or a reduction in dialogue in recent films in general. Maybe you’ve already looked at that?