What percentage of film producers are women?

Last week, I looked at producers' careers and this week I am going to use the same data to look at how the picture differs between male and female film producers.

This research harnesses my dataset of every feature film released between 1949 and 2018 inclusive. This includes 631,365 producer credits across 274,991 films and 269,385 individual producers.

For today's article, I'm going to assume that readers are familiar with the different types of producing credits. If you would like a quick primer then head over to last week's article, entitled On average, how many films does a producer produce? In the opening section, I have detailed the different credits and what they mean.

What percentage of film producers are women?

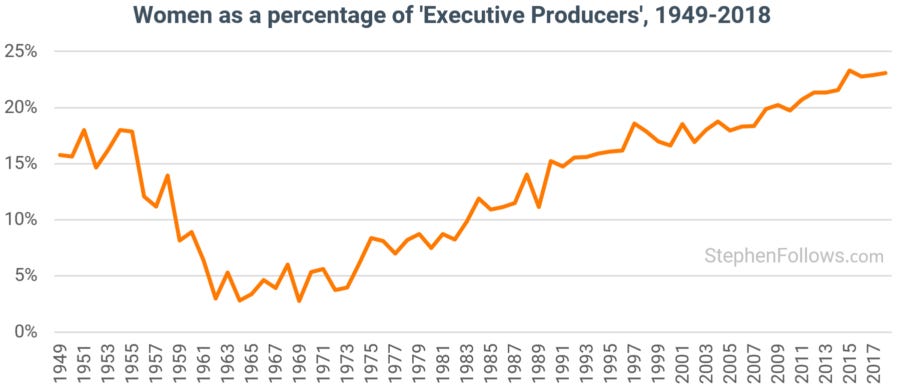

In 2018, 26.4% of all producing credits on feature films went to women. This is considerably higher than in the 1950s and 1960s, when the average was just 4.6%.

Not all producing credits are created equal, so let's zoom into the top producing credit, that of 'Producer'. As the chart below shows, female participation among full producers has been growing steadily since the late 1960s.

The picture of Executive Producers is similar, save for the unusually high representation in the 1950s and 1960s. This is almost entirely down to one rather incredible woman. Narcisa de Leon (also known as Doña Sisang) didn't start in the film industry until she was 61 years old but she went on to executive produce 285 movies between 1940 and 1960 - an average of more than one a month!

When we overlay the last four decades, we can see a clear pattern emerge - the more senior the position, the fewer women in that role.

How does the scale of a movie affect the likelihood of female producers?

The trend of 'increased seniority equals fewer women' matches the work I have conducted in the past on directors. This is also present when we look at the budgets of the movies in question.

As film budgets rise, the likelihood of there being a female producer falls. Women account for 23% of producers for movies budgeted under $5 million, but just 16% of films budgeted over $50 million.

When we split by the different types of producers we can see that the budget increase affects the roles slightly differently.

Associate Producers are the only type of producers where women are more prevalent as budgets rise. And on the flipside, the role of Line Producer has a dramatic drop of female involvement as the scale of the project increases.

Are female producers less likely to make a second film?

One common factor among other key creative roles in the film industry is that women are less likely to make additional films than their male counterparts. To see if this is also true for producers, we can look deeper at a finding from last week's work on producers' careers. Last week, I showed that over the past half-century, producers make an average of two movies within five years of their first (so the original movie plus one more). Let's split this data by gender and see what it reveals.

The chart below shows that gender is not a key factor in the likelihood of producing a second movie within five years of the first. In the 1990s, the gap between male and female producers did indicate that men were slightly more prolific but this has closed and for the past two decades there is no difference.

Before we finish, I thought I'd share two other findings on this topic - genre and country of origin.

Which film genres are more likely to be produced by women?

Female producers are more prevalent among Family, Romance and Musical films (26%, 25% and 24% of 'Producers', respectively) and least among Action, Horror and Crime movies (16%, 17% and 17%).

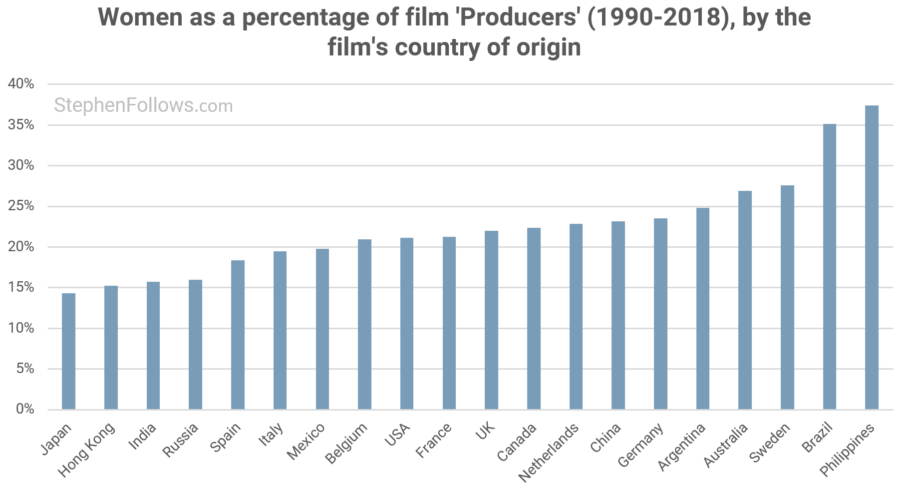

Which countries are more likely to make female-produced films?

The worldwide rise in female producers we saw in the first chart is a trend reflected in all major film-producing nations. However, some are rising quicker than others and some come from a pretty low base.

Women account for 37% of 'Producers' among films made in the Philippines between 1990 and 2018. Other countries with strong female representation are Brazil (35%), Sweden (28%) and Australia (27%). At the other end of the spectrum is Japan, with an average of just 14%, although in recent years their representation has improved (in 2018 it was almost 20%).

Notes

The data for today’s research came from a number of places, principally IMDb, The Numbers, Wikipedia, Box Office Mojo and OMDb. My dataset is of all feature films made and listed on those sites. Genre classifications were from IMDb, where possible. The years refer to their first public release date, not when the films were shot. I was able to find budget figures for 9.8% of films made from 1990 onward. I believe that the vast majority of the films for which I couldn't find a budget figure are small or micro-budget movies.

To determine a producer's public gender, I used publicly available data, pronouns (such as in biographies) and first name analysis (i.e. if 99% of people called Daniel are male then I have regarded every Daniel with an unknown gender as male). This provided a clear gender of 93.7% of producers. I appreciate that this research takes no account of gender fluidity or other forms of self-identification. That’s not a conscious choice but rather a consequence of doing research at this scale. If anyone can suggest a way of taking this on board in the research process then I am very keen to hear it. Please drop me a line and we can talk it through.

If there was anyone for whom I could not reliably determine a gender, then they were not included in the charts which show a percentage split between male and female producers. Although this is not ideal, I have no reason to think that these people skew towards one gender over another, and they were also a small percentage of my overall dataset.

For the vast majority of the period I studied, producers are extremely likely to have publicly identified in a binary manner, no matter their true feelings or identity. This research speaks to how producers are judged from the outside and it’s the public-facing gender identity that matters most when it comes to discrimination.

Finally, I have tried to be respectful to all in my choice of language when discussing gender and identity. If I’ve misspoken somewhere, drop me a line and I’ll fix it. I aim to use the word “women” where possible as it relates to identity, not biological sex. The only exception is where it would be grammatically incorrect to do so – both “woman” and “female” are nouns but only “female” is an adjective and a modifier (i.e. “female producers” is correct while “women producers” is not).

Studies of this nature are needed into other under-represented areas, taking into account class, race, socio-economic status, location, to name but a few. Sadly it is much harder to study these topics at the scale and depth I can for gender. I am always on the lookout for ways to do so – please do get in touch with any ideas. Click here to read more about my (as-yet-incomplete) attempts to study race in film.

Epilogue

Regular readers will know that I often research and write about female representation in the film industry. This blog is designed to cover all manner of topics, issues and sectors and so I have to somewhat limit the number of gender studies I conduct.

I am considering a spin-off side project where I can conduct more studies on issues of representation and go much deeper than I do right now. The only thing holding it back is funding, so if you or your organisation are interested in supporting such a project, get in touch and I'll share more info.