How many people does it take to make a film in the UK?

One of my most popular past articles looked at how many people work on a Hollywood film. I found that from 1994-2013, the average top US-grossing Hollywood film had 588 people in the crew. Despite being a few years old, the article still regularly prompts questions from readers, so I thought I would tackle two of the most frequently asked questions today: is this the same for UK films and how do crew sizes change at different budget levels.

I studied all feature films made in the UK between 2008 and 2014 and found…

There were over one and half million crew credits on UK films 2008-14

The average UK film has 778 crew credits

Films budgeted under £150,000 credited an average of just 32 people

Films costing over £30 million have an average of 1,140 crew credits

The departments where the increased budget has the biggest effect on employment are Visual Effects and Stunts

On average, bigger budgets actually lead to fewer Directors, Production Designers, Composers and Directors of Photography

How many people does it take to make a film?

Across the 1,941 films, there were over one and half million credits (well, 1,511,017 to be specific), meaning that the average UK film had 778 crew credits. However, this mixes together a wide spectrum of films, so we need to split it by budget level to get a better picture of what’s going on.

Films in the lowest budget bracket (made on under £150,000) credited an average of just 32 people. The actual number of people who worked on the film is likely to be slightly lower, as it’s not uncommon for one person to take on multiple roles. For example, in a previous research piece I showed how 58% of UK films were made by writer-directors, which means that one person is receiving both directing and writing credits.

As we move up the budget level, we see that crew sizes increase relatively slowly, with films budgeted between £1 million and £2 million crediting an average of just under 100 people. However, when we get to films budgeted over £30 million we see a huge increase: those films have an average of 1,140 crew credits - 36 times more than that of micro-budget films

The effect of a bigger budget

The fact that bigger films employ more people is not surprising as the wages are a major part of why films are so expensive. However, increasing budgets affect each department differently (i.e. doubling a budget doesn’t result in a doubling of staff across the board).

The departments where the increased budget has the biggest effect on employment are Visual Effects and Stunts.

Money don’t mean a thing

For some departments, an increased budget doesn’t necessarily mean more staff members. The average sound department on a micro-budget film is made up of 4 people, and on a film costing over £30 million there are 35 sound credits. While this is a big increase (nearly 9 times as many people), it is a significantly smaller increase than Visual Effects (crews increase 148 times between micro and top budgeted films) and Stunt departments (which are 36 times larger).

How many cooks are in the kitchen?

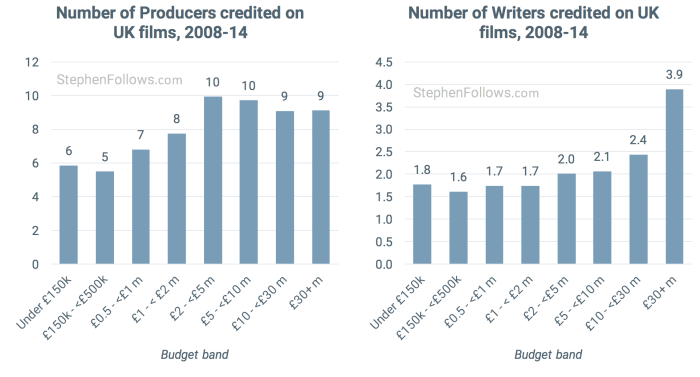

So far, I have focused on the departments, but it's also possible to look at the key creative roles, such as writers, producer, directors and other Heads of Departments (HODs). Common sense tells us that even if a budget grows hugely, a film is not likely to suddenly hire more directors. However, there are other key creative roles where there's no natural limit to employment, such as writers and producers.

I looked at the average number of people employed on micro (i.e. <£150k) and big (>£30m) budgeted UK films for nine of the top creative roles. I found that bigger budgeted films actually had fewer Directors, Production Designers, Composers and Directors of Photography on average.

The five remaining key creative roles (Writers, Producers, Casting Directors, Editors and Costume Designers) increased in number as budgets rose.

In the past, I've studied related topics including career patterns for UK film creatives (only a fifth of writers, producers and directors make a second film), how many people work in the UK film industry (around 70,000 in 2013) and how many producers it takes to make a Hollywood film (just over 10 in 2013).

Notes

Here are a collection of notes relating to today's research...

The films - During 2008-14 inclusive, 2,085 feature films were made in the UK of which 1,941 have online crew listings (93%). The raw list of films came from the BFI and then I updated and added to it. I then used public sources (mostly IMDb) to determine how many people worked on each film.

Cast - The cast members are not included in crew counts.

Time served – My numbers take no account of the length of time each person worked on the production. This means that a rigger who worked on set for one day, or a VFX artist working on one shot will receive the same weighting as the cinematographer or director.

Seniority – My research is inadvertently Marxist, offering each person equal status to another. Anyone who has been on a film set will know that they are run more along the lines of Stalin than Marx. Consequently, we cannot infer that the bigger departments are more important. We can simply say that they had more people credited to them.

Self-Reporting Bias – The credits for films on IMDb are submitted by production companies, studios, the public and some chap in a pub called Bernard; i.e. anyone can suggest a credit. IMDb requests evidence from the submitter and larger films can verify their credits as complete but this cannot completely eliminate the nature of self-reporting data being naturally skewed towards those who are the most proactive / self publicising.

Epilogue

Last’s week’s article contained 72 tips for visiting the Berlin Film Festival and European Film Market. Having just returned from Berlin, I feel it important to report a 73rd tip which I uncovered while out there... "Run a blog which highlights the organisations who run the best parties - they will send you invites". I am indebted to all of the organisations who sent me invitations after seeing their event mentioned in the article.

My two cents is that the best party was hosted by the Swedish Film Institute. It had everything you would expect from a top notch party (great food and drink, lovely location, etc) and some things that only the Scandinavians seem to have mastered: it was a family-friendly affair with babies and strollers, plus their CEO, Anna Serner, spent hours at the entrance personally greeting all the guests as they arrived. In my experience, few people at that level take the time, so all credit to Anna.