How much is the average film festival submission fee?

A deep dive into 4,631 festivals shows how routine submission fees have become, and how high some of them now run.

Last week in an article about how long your film needs to be to be accepted into film festivals, I mentioned in passing that a 90-second short film was eligible at nine out of ten film festivals I studied, but doing so would cost $312,951 in submission fees.

That was just a fun, back-of-the-napkin figure, based on a quick average cost. It caused a lot of conversation and follow-up questions, so I returned to the topic to apply a little more rigour and detail.

I gathered submission fee data for 4,631 film festivals and set about understanding what filmmakers should expect to pay for each submission.

Soon after I had started the research I realised it was going to be more complex than I first thought. Film festivals tend to have multiple categories as well as sliding fees based on how close the submission date is to the festival.

The categories might relate to:

Running time. Shorts and features rarely compete with each other but many festivals go one stage further and further divide short films by length, such as under 90 seconds, 2 to 5 minutes, etc.

Format. This could include live action, documentary, animation, experimental and, more recently, AI-generated.

Genre. Some festivals have an overall genre focus while others have particular genre strands.

Themes. These could include sports, dance, LGBTQ+, faith or social issues.

Locality. The background, nationality, or home location of the filmmaker(s) may mean they are included or excluded from certain strands.

Once you have picked your categories, you will be charged a different fee based on the date. The typical deadlines are:

“Early” - This will typically be the first opportunity you get to submit your film and could be as much as a year before the festival will actually take place.

“Regular” - This has no real meaning beyond the fact it’s between the others.

“Late” - In some cases this is the final deadline, while in other cases it’s the same as above.

“Final” - In theory, this is the very last date you can submit your film and still have it considered for the next edition of the festival.

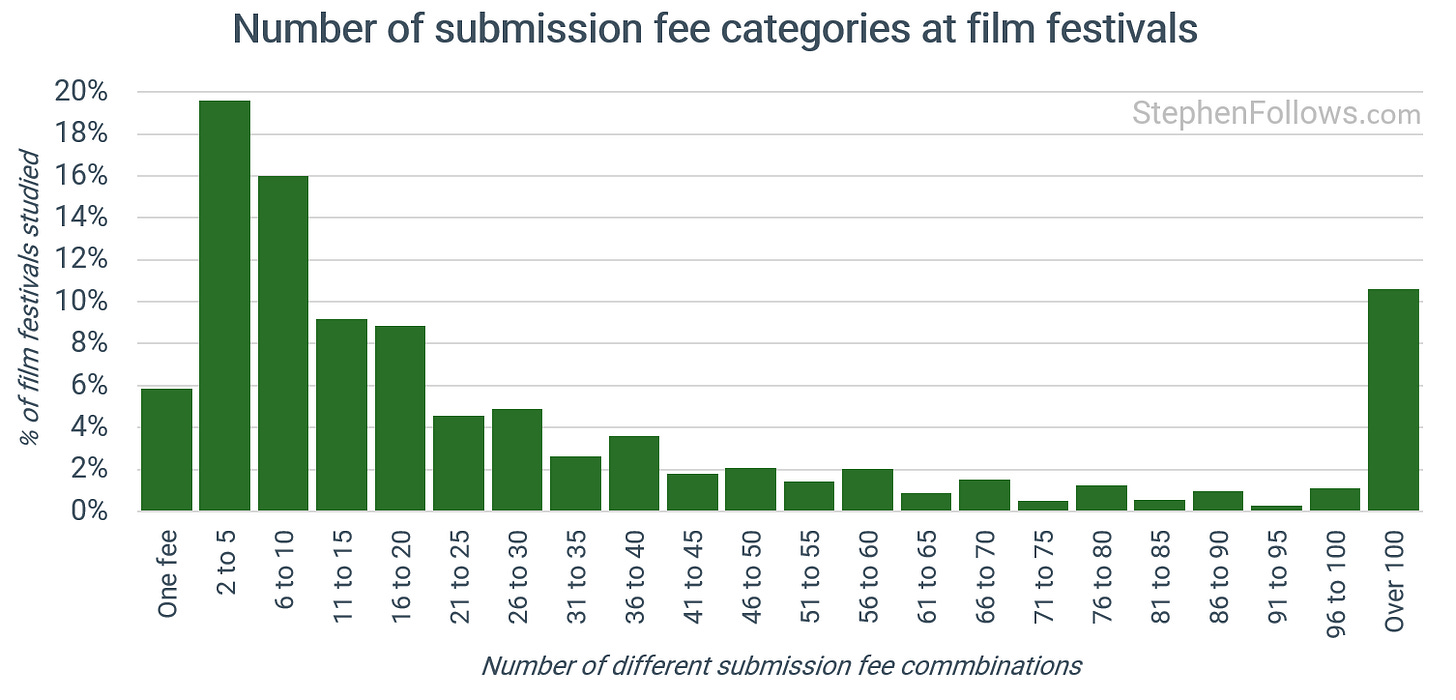

The average festival I looked at had 37.5 different fee options. Yes, that’s right - almost 40 combinations on average!

But this average is being dragged up by 10.6% of festivals who offer more than 100 combinations. Across the dataset, half of festivals had 15 or fewer submission fee combinations each year.

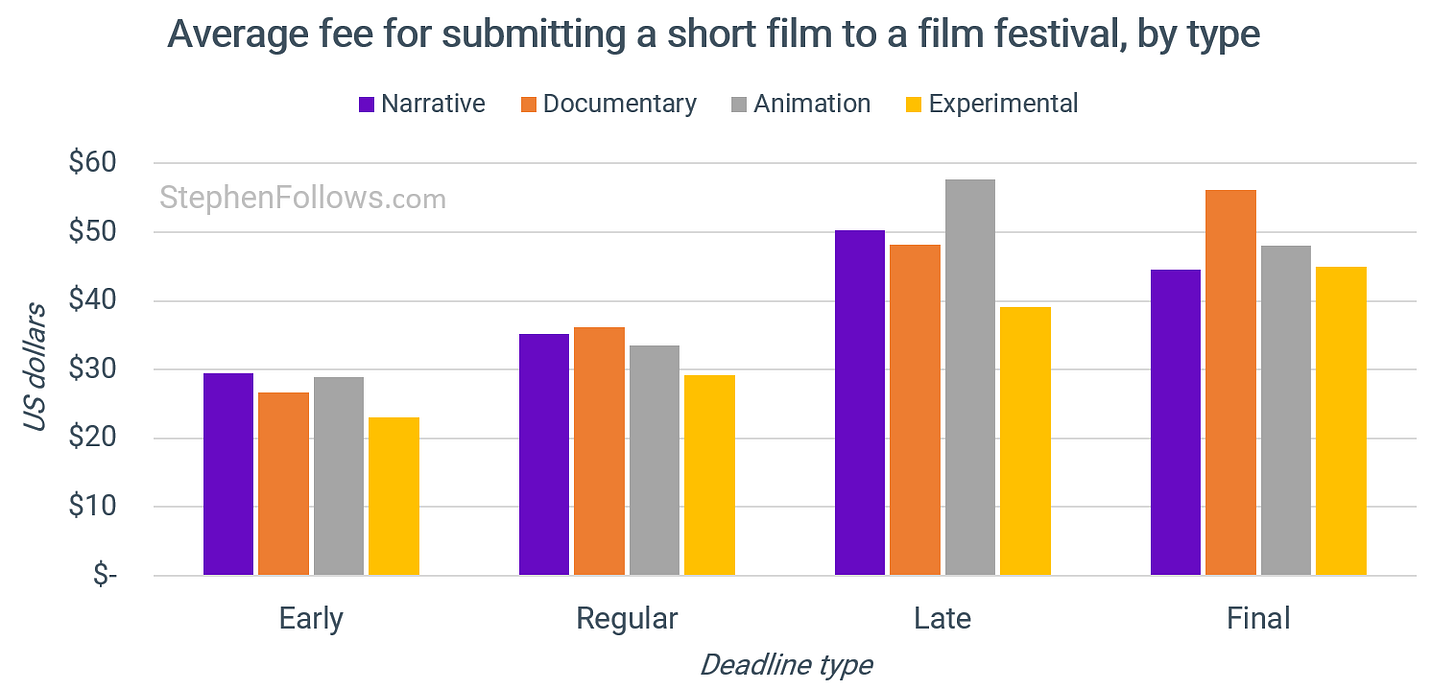

If we split the fees only by whether it’s a short or a feature, and by the time-based deadlines, then we discover that the average submission fees for short films are between $30 and $55.

For features it’s between $47 and $87.

For whatever reason, film festivals have collectively decided that experimental filmmakers have less money than live action or animation filmmakers.

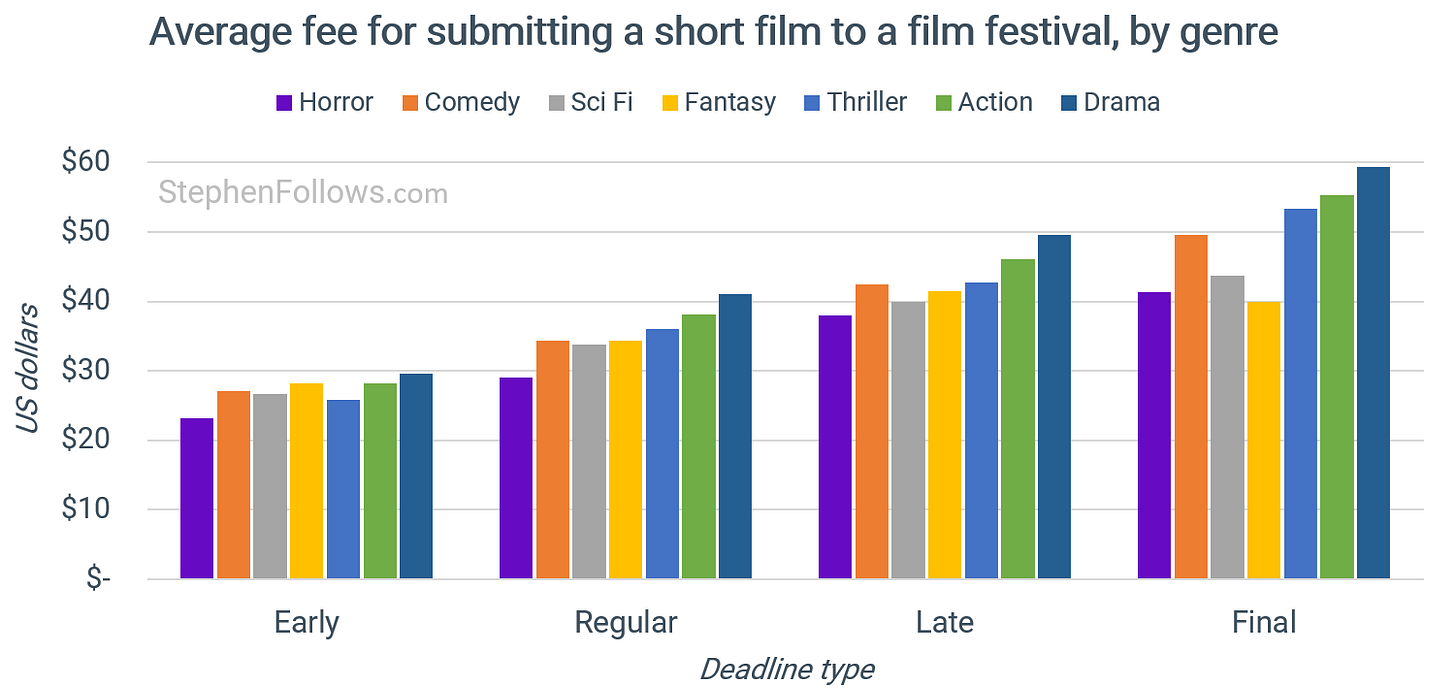

And that horror filmmakers are the cheapest.

Why do festivals charge submission fees?

There are two answers to this, depending on the festival and who’s answering the question:

Because running a festival is expensive. The majority are non-profits, both in the sense that they are registered charities and that they typically lose money each year. When the indie stalwart the Raindance Film Festival opened up their accounts to me a few years back, we learned that submission fees accounted for a third of their total income.

Because they know filmmakers will pay. A more cynical view of submission fees is that festivals are charging money based on the hopes and dreams of filmmakers. The decision of which to submit to is typically made on very little information - just the name, self-written description and some photos/graphics.

There’s even a question over what the fees actually cover. In 2024, WorldFest-Houston cancelled all of its public screenings but refused to return submission fees. The organisers argued that fees cover the cost of judging and administration, not the screenings themselves, and so no refunds were due.

Filmmakers and festivals also disagree about how much of a film the festival is obligated to watch in return for the fee. Filmmaker Chris Suchorsky sent separate Vimeo links to each festival and tracked the views. Some festivals did indeed watch it all, but some only watched a small amount of his film and in at least one case there were zero views, despite the festival banking the submission fee. Only when they queried the festival did a handful of “plays” suddenly appear.

It’s worth noting that Chris Suchorsky’s Vimeo experiment took place quite some time ago, and that Vimeo themselves have since acknowledged that their analytics are not always 100% reliable. In addition, festival screeners are often based all around the world, making it difficult to connect a viewing location directly to a particular festival office. But the concept behind the method remains a useful illustration of filmmakers’ concerns about whether their work is fully considered.

A brief history of film festival submission fees

The very first festivals didn’t charge at all. Venice, Cannes and Berlin were funded by governments and tourism boards, and films were submitted through ministries of culture, not individual filmmakers. A filmmaker couldn’t just put their film in the post and hope for the best.

That changed in the 1970s and 80s, when independent filmmaking expanded and new festivals like Toronto and Sundance appeared. These events didn’t have state backing, and they needed their own income streams.

The spread of VHS was the real turning point. For the first time, filmmakers could copy and mail their work cheaply. Submissions multiplied, and festivals introduced fees both to cover the paperwork and to slow the flood. What had once been a rare administrative charge became the standard way to fund and filter the growing circuit.

The next big shift came online. In 2000, Withoutabox centralised submissions and promised to simplify life for filmmakers and festivals. At first it worked, but over time the tale turned sour.

Withoutabox controlled the market through an unusually broad patent, covering little more than the idea of submitting films to festivals online. It was granted in 2001 and effectively blocked rivals for more than a decade. IMDB (and therefore Amazon) bought Withoutabox and aggressively defended their patent. Film festivals grew to hate Withoutabox but the patent meant they had to keep on using it.

FilmFreeway launched in 2014 with the opposite pitch: free to use, HD screeners, lower commissions. They stood up to Withoutabox via a mix of smart thinking and dirty tactics. They called Amazon’s bluff and took the festival scene by storm.

Withoutabox tried to fight back, via under the counter payments to festivals to stick with them, but they were no match for the new contender and finally shut down the service in 2019.

FilmFreeway itself was bought by Backstage in 2021 and is now the dominant leader for festival submissions. Most filmmakers rely on it and most festivals list on it. But with near-total dominance, some of the old grumbles are returning about commissions, about reliance on a single gatekeeper, and about whether we’ve just swapped one monopoly for another, albeit not one locked in by an overly broad patent.

The sheer ease of submitting has also fuelled a fee-driven gold rush. Thousands of festivals, both serious and questionable, have leaned into the model, multiplying categories and deadlines in order to capture more submission income.

Further reading

If you want a deeper dive into festivals, here are some past articles which may be of interest;

Scandal behind the Withoutabox / FilmFreeway beef - US6829612: Withoutabox's Dirty Secret, then the fight began The seismic shift in the world of film festivals and ended here What's changed in the world of film festivals?

Survey of film festival directors - What film festival directors really think

Financial transparency - Full costs and income of a major film festival - Raindance Film Festival

Tips and advice - How to prepare for ANY film festival, and specialised articles for Cannes, Sundance, Berlin, Toronto, and SXSW.

Notes

Today’s research is based on the fees charged by 4,631 film festivals. The figures came from official festival websites, listing sites and public aggregators. I translated the figures into USD for comparison.

When I’m talking about fee combinations I am not including the discounted version of fees that festivals have to offer to paying Gold members of FilmFreeway. So if you want to include those discounts, double all the combination counts!

Epilogue

I was expecting there to be a few instances of festivals charging very high fees but I was shocked by the gall of some festivals. There is no justification I can think of for charging over $100 for short film submission. It doesn’t matter how specialised the festival, nor how late the deadline is, nor how long the festival has been running - it’s just wrong.

I decided against naming and shaming individual festivals in this article, because I can’t do enough due diligence in each case to know if it’s the exception. Hypothetically, some festivals could offer terrific value (i.e. feedback, hotels, private jets, etc), and/or some other kind of advantageous small print (i.e. returning fees if not selected, etc).

Therefore, I thought it best to err on the side of caution and not mention the most egregious cases.

But there’s no doubt that there are more than a handful of festivals outright exploiting filmmakers’ hopes and dreams via exorbitant submission fees. Shameful.

What a great follow-up. Thank you!