Six ways the film business is changing

The coming of a new year always makes me pause and take stock. It's a time when people traditionally ponder what they're up to, where they're going and what they want to do next. So I have spent some time thinking about what's happening in the film business and where we're going. I don't like predictions (see the Epilogue for more about this) but there are a few trends which give us clues about the next few years in film.

Each of these trends really requires several charts and graphs, but just in case you had other plans for today I have limited myself to no more than one for each trend. I have added some links for further reading, for those of you who feel that my One Graph Rule is like the movie 300 (i.e. ludicrously Spartan).

Trend 1: A decline and re-focusing of micro-budget filmmaking

Shooting a feature film used to be very hard and very expensive. When Danny Boyle was trying to make his first feature, Shallow Grave, in 1993, he was told he was mad for trying to make a film on a mere £1 million (£1.9m in 2017 money). They were so stretched that they had to sell props from the early scenes to finance the filming of the final scenes.

Since then, there has been a technological revolution in all areas of film production and post-production. You don't need to be the world's greatest line producer to know that nowadays if you wanted to make a film starring three unknown actors shot in an average modern house then you wouldn't need to raise £2m!

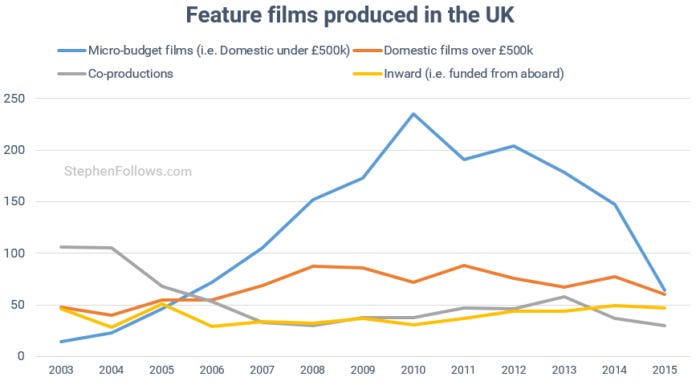

These new, cheaper, easy-to-use technologies started to have an impact around 2005 and led to a boom in micro-budget feature films in the late 2000s. The high water mark was in 2010 when 235 films under £500k were shot in the UK (two-thirds of all films shot that year!) Micro-budget schemes started to pop up, the most successful of which (Film London's Microwave and Creative England's iFeatures) have become firm fixtures on the journey for many new filmmakers.

However, in recent years, we have seen a crash in the number of such features being made. The reasons for this crash are slightly mysterious (see links below for more detail) but one thing is clear - the current generation of filmmakers is not as keen to shoot a micro-budget feature film as their predecessors.

Does this mean we will see the end of micro-budget fare? Probably not, for two reasons. Firstly, there will always be entrepreneurial filmmakers who choose to club together a little bit of money and get the film made. Secondly, their purpose is changing. In the past, micro-budget filmmakers adopted the same justifications and intentions as filmmakers of larger films; i.e. to make money. The truth is that almost no micro-budget feature films make money and so it has become ever-harder to make the case to commercial investors. However, they are great places for new filmmakers to learn, to get noticed and to meet peers. Public funding bodies know that they can help more filmmakers by funding five £150k films than if they fund one £750k film.

And so that's where we are - fewer micro-budget films, with an increased focus on training and proving oneself, rather than as commercial vehicles.

Further reading

What’s happened to UK low-budget film production? (StephenFollows.com)

Film industry responds to falling UK film production (StephenFollows.com)

What are the highest grossing UK low-budget films? (StephenFollows.com)

How many feature films are shot in the UK each year? (StephenFollows.com)

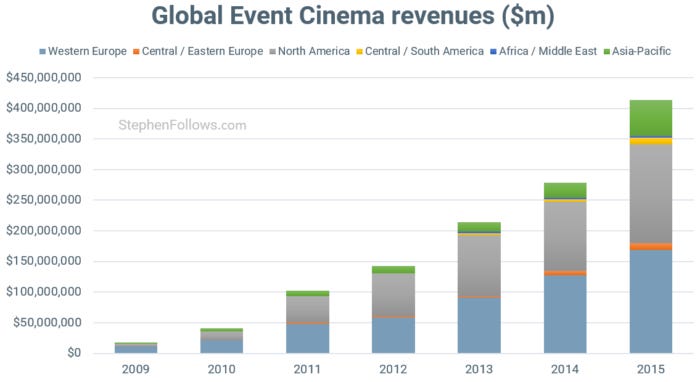

Trend 2: A growing split between ‘Big Cinema’ and ‘Specialised Cinema’

Each week in the UK, an average of almost fourteen new films are released in cinemas - double the figure fifteen years ago. Cinema attendance has only risen by 16% over the same period, meaning that movies have had to work harder to be seen. Added to this, the top 50 movies each year grossed around three-quarters of the annual box office revenue, meaning the remaining 650-odd movies are all competing for the other 25%.

Partly in response to this change, we are starting to see innovative variations on the traditional cinema-going experience including:

Crowdsourced movies (such as those organised by ourScreen)

Live events in cinemas (such as National Theatre performances broadcast live)

Immersive theatre / cinema hybrids (such as Secret Cinema).

Last year, Secret Cinema's production of The Empire Strikes Back grossed £6.3m, on a par with The Man From U.N.CL.E.

At the same time, the big Hollywood blockbusters (known as 'tentpoles') are getting bigger, with ever-larger advertising campaigns and they rely on 3D and IMAX for a large chunk of their income.

If this split continues, then it could lead to an even greater gulf between what I like to call 'Big Cinema' (i.e. global cinematic 'events' based around spectacle) and 'Specialized Cinema' (i.e. more local, personal and bespoke cultural events).

Further reading

The rise and rise of alternative cinema content (StephenFollows.com)

Alternative content at cinemas draws in the masses (Financial Times)

Who's who in event cinema: A guide to major alternative-content suppliers (Film Journal)

How many British films secure theatrical distribution? (StephenFollows.com)

Trend 3: Realignment of release windows

When I was a teenager in the 1990s, being a film fan was all about waiting. We had to wait for movies to make their way from America to the UK, wait for them to move from cinemas to the video rental shop, wait if you wanted to own a copy and wait years before they appeared on TV. In the past two decades, the release windows for movies have shifted significantly, and they have also become more diverse.

Just some of the shifts we've seen include:

International delay - In 1995, UK cinemas showed Hollywood films an average of 134 days after the US, whereas in 2015 it was just 9 days

International first - None of the top 100 US grossing films released in 1994 came out in the UK first. In 2014, 38% of Hollywood films came out in the UK on the same day or before the US.

Shrinking theatrical-to-DVD window - The gap between cinema and DVD releases of studio films has fallen by 34% between 2002 and 2014.

VOD overtaking DVD - In 2014, films outside of the top 100 box office chart arrived on VOD an average of 33 days before DVD

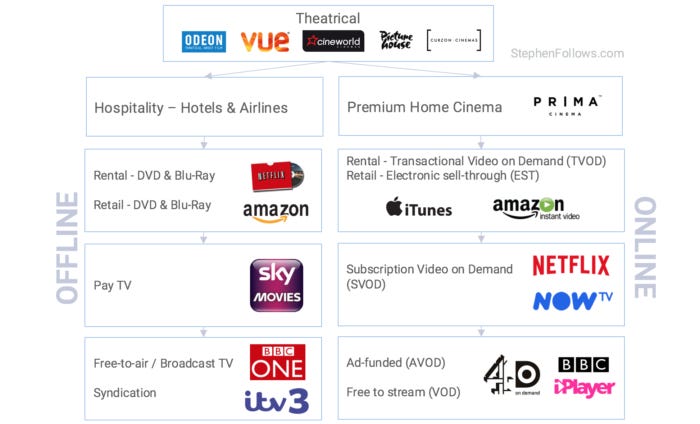

The timing of release windows used to be pretty much universal whereas today distributors are more open to shifting the order for the best price. The third window (i.e. after theatrical and hospitality) could be Home Entertainment (i.e. DVD and Blu-Ray), EST (i.e iTunes rental), TVOD (i.e iTunes purchase), SVOD (i.e. Netflix) or TV (i.e. Sky Movies).

Below is my best illustration of how the release windows sit in 2017.

Further reading

How long between UK and US movie release dates? (StephenFollows.com)

Major Studio Theatrical Release Windows (National Association of Theatre Owners)

Changes To Hollywood Release Windows Are Coming Fast And Furious (Forbes)

Trend 4: Increased demand for female-focused films

When the new female-focused Ghostbusters movie was announced, a small but vocal group of people leapt onto Twitter to complain about how the movie was retrospectively "ruining their childhood". The internet decided that the movie was a referendum on whether women are a Good or Bad thing (i.e. "Do you want to leave the sexist world of the 1970s or remain?")

The pressure built, battle-lines were drawn and its eventual lackluster performance at the box office was viewed as either proof that women ruin everything or that men can't cope with women in power.

Obviously, no one movie should be used to 'prove' anything. The trend towards female-focused Hollywood movies did not start (and will not end) with Ghostbusters. It is just the largest recent example of how Hollywood has woken up to the increasingly active female audience in cinemas.

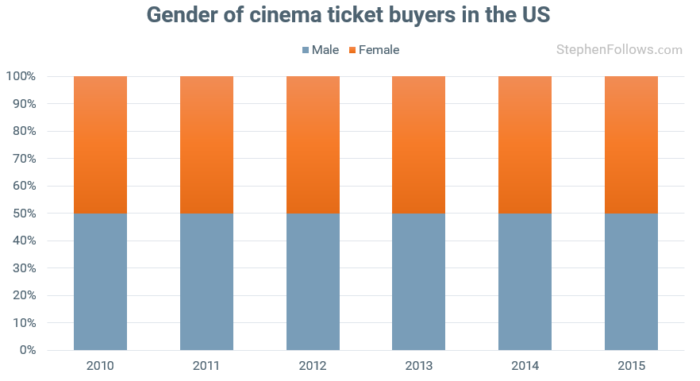

Interestingly, this doesn't come down to more women going to the cinema. (Well, female cinema-goers are slowly increasing but at the same rate as male cinema-goers). In the US, the audience of frequent cinema-goers has been 50:50 for all of the recent past.

What's changing is women's tolerance of seeing male-focused movies. As a result there are an increased supply of movies aimed at women. Previous generations of women were more likely to put up with seeing movies targeted at men because men were expected to buy the tickets (and therefore more likely to choose the movie). Increasing gender parity in the world has (finally) been noticed by Hollywood and they are keen to cash in on this shift.

Further reading

'Your film has ruined my childhood!' Why nostalgia trumps logic on remakes (The Guardian)

'Ghostbusters' Reviews Prove the Reboot’s Point About Sexism (Teen Vouge)

Why Female-Centric Films Outnumber Male-Skewing Action Movies (Hollywood Reporter)

2016’s Feminist Features: 6 Ways Women Dominated the Best Movies of the Year (IndieWire)

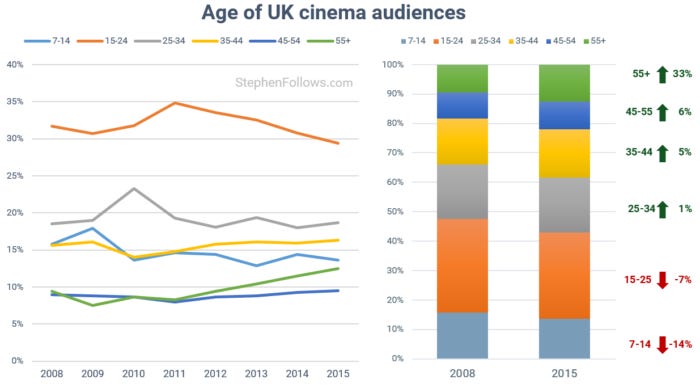

Trend 5: An ageing film audience

There has also been an increase in the number of movies aimed at older audiences. The film business has historically been very bad at recognising, tracking and supplying films to older cinema-goers. Most surveys of cinemagoers lumped everyone older than 45 years old into a "45+" category and it has only been in the past few years that we've seen the emergence of a "45 to 55" and "55+" categories. (Even then, average UK life expectancy is 82 years old, meaning that the "55+" category covers 42% of the average adult life).

The trend towards female-focused films was due mostly to changing attitudes, whereas the emergence of what the industry calls the 'Grey Pound' (I prefer 'Senior Cinephiles') is due to a mix of factors, including:

Greater number of older people in the UK population at large.

Life expectancy is rising.

Older people are more active (physically and socially) than ever before.

The Baby Boomer generation grew up on cinema.

Most of the other forms of entertainment which rival cinema-going are technology-based and therefore more readily embraced by the younger generations.

These factors have meant that the "55+" segment of the UK cinema population has grown by a third between 2008 and 2015. This audience has led to box office successes such as The King's Speech and The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel.

Further reading

How older viewers are rescuing cinema (The Guardian)

Emma Thompson criticises 'grey pound' films for older audiences (BBC News)

Graying Audience Returns to Movies (New York Times)

Rise of the silver-haired screen: Older people take largest share of cinema audiences (The Independent)

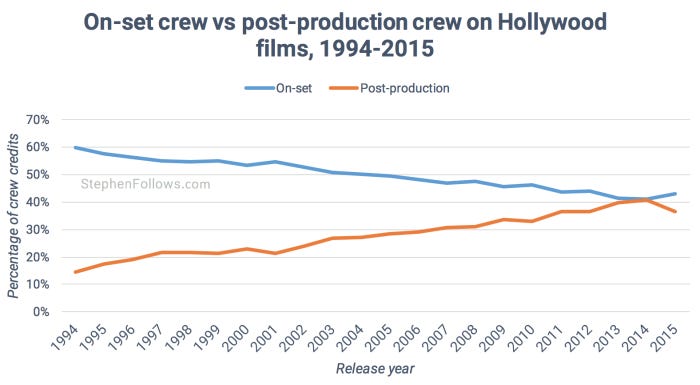

Trend 6: The employment shift towards post-production jobs

In 1994, only 15% of the people who worked on the average Hollywood movie worked in some form of post-production role (i.e. editing, visual effects, sound, music, etc). Twenty years later, this has ballooned to 41%, thanks mostly to the increased quantity and complexity of visual effects.

On the face of it, this doesn't really matter; the industry is always changing and it is unsurprising that the number of technology-based jobs has increased. However, there is a potential for concern for any country whose film sector heavily relies on such jobs. By their very nature, post-production jobs are easier to offshore and move overseas than on-set roles.

This means that countries which currently enjoy high levels of VFX employment (such as the UK and New Zealand) should consider the potentially huge implications of minor changes to regulations, support and funding they manage. For example, a minor change to the UK Film Tax Relief scheme which reduces the value of British post-production crew could lead to a huge numbers of job losses in UK VFX houses.

I'm not predicting that this will happen, just pointing out that the over-reliance of jobs concentrated on a highly peripatetic sector is worrisome, in much the same way that the highly-connected housing market and concentrated network of banks in the US led to the 2008 financial crisis.

Further reading

Do more film crew members work on-set or in post-production? (StephenFollows.com)

From Harry Potter to Gravity: how British VFX talent is leading the world (The Guardian)

How many people does it take to make a film in the UK? (StephenFollows.com)

How London Leads The World In Movie Visual Effects (Londonist)

Epilogue

Regular readers will know that I'm very wary about making predictions and suspicious of those who do. There is so much that is unknowable about the world in general and the film industry in particular that it seems like a fool's errand to spend one's time trying to guess the unguessable. I'm a fan of the work of Nassim Taleb who has made the study of randomness his life's work and written a number of brilliant (if a little angry) books on the topic. Ironically, he was one of only a handful of people to foresee the possibility of a big financial meltdown in his 2007 book 'Black Swan'. (I was disappointed by the film version - too little philosophy and too much flouncing).

Our industry is particularly addicted to trying to foresee what's to come, due to its unpredictable nature and the chance for high rewards for the rare successful outliers. For example, only about 7% of British films end up in profit but if you are able to make The King's Speech then you can be sure of earning enough to retire and play golf all day.

Success in the film industry is heavily dependent on luck. That's not to diminish people's talent, dedication and hard work, but it's pretty obvious that those things are not enough on their own. I know of a number of extremely hard-working, talented people who are yet to get the recognition they deserve and yet could write a phone book full of the names of lazy, mediocre, successful film professionals.

To me, it seems that success in the film industry comes down to three factors:

Hard work. Putting in the hours, not taking 'no' for an answer, researching how the industry functions, keeping up on industry changes, applying for every fund or scheme, networking like crazy and general persistence.

Circumstance. Living in the right place, being able to work for low or no wages, being whatever race, age or gender your part of the industry rewards.

Luck. Timing, being in the right place at the right time, someone seeing your work when they're in the right mood, a film hitting a Zeitgeist, your leading actor achieving fame after you've cast them, etc.

You can certainly affect the first on that list in a big way and, to some degree, the second may be able to be shifted over time (such as moving house and fighting against discrimination). But the last is not completely in your control. It's true that the more networking events you attend, the greater your chance of being "lucky" and bumping into the right person, but this only shifts the dial a tiny amount. Of the people who network at every moment they can, only a handful will make a career breakthrough this way. Buying a second lottery ticket increases your chance of becoming a millionaire but it's still in the lap of the Gods.

Comedian Bo Burnham expressed this rather well when Conan O'Brien asked him how someone can get into his business:

The system is rigged against you. Your hard work and talent will not pay off... Don’t take advice from people like me who have gotten very lucky. Taylor Swift telling you to follow your dreams is like a lottery winner saying liquidize your assets, buy powerball tickets, it works.

He added:

And we’re tall white guys [meaning him and Conan, not him and Taylor Swift] We overcame nothing to be here. There was nothing standing in our way and we barely got here. You have no chance.

I don't actually agree with Bo that you should give up (and perhaps some of his advice is given for comedic effect) but he brilliantly sums up how much of the process is out of your hands. You should follow your dreams not because you will definitely succeed but because you're likely to find happiness and fulfillment along the way.

But I digress. My point was about the folly of predicting our industry. If we acknowledge that luck plays a big part in success, then we are also accepting that chance and happenstance play a big role in shaping the future. That's not to say that everything is unknowable. The larger the trends, the more we may be able to see them coming (such as the ageing population leading to an increased audience for films which appeal to older generations). But if we pick a particular film or person and ask "Will they succeed?" we simply cannot know with any degree of certainty.

And the further in the future we seek to predict, the greater the chance we will have no better odds than a chimp throwing darts at a list of all possible outcomes. Over time, even the most powerful companies and people fall from grace and unpredictable successes rise. Only 12.5% of the companies in the Fortune 500 in 1955 were still in the Fortune 500 in 2014. Furthermore, no-one a couple of decades ago could have predicted the power of Apple, Google or Facebook (currently the 1st, 4th and 29th most valuable companies in the world).

This explains my slight weariness towards the constant clamour for predictions. A few years ago, I wrote a piece detailing the economics of Oscar campaigns, and as a result, each year I receive well over a hundred press requests for my Oscar picks. I'm not sure if it's laziness on their part or if they genuinely think I can foresee who will win, but either way, I can't.

And as for Brexit - who knows?! Who possibly can know at this stage? Every time I am asked by members of the press for my thoughts on Brexit I am tempted to answer thusly:

The result of the Brexit vote will become clear when we see how film audiences respond to the film industry's response to the deal which is struck in response to the response of the UK to the response of the EU arts bodies in response to the wider Brexit deal which responded to the EU’s response to the UK government's response to what they think the UK population thinks they think.

Simples!

I hope my trends are useful and my rantings on predictions were tolerable. Here's to a happy, healthy and successful (however you define that) new year!