Last week, I looked at the average number of people who work on feature films in the UK (778, although it varies quite a bit depending on the film’s budget). This prompted three people to independently ask me the same question: “How many film crew members work on set compared to those working in post-production?” It’s a good question as it touches on a few interesting topics. Firstly, it speaks to the huge number of diverse jobs performed by people in the pursuit of making a film. Secondly, it gives us a way of looking at how the composition of film crews has changed over time. Finally, it gives new entrants to the industry a better idea of how many people may be on-set during a shoot.

Last week, I looked at the average number of people who work on feature films in the UK (778, although it varies quite a bit depending on the film’s budget). This prompted three people to independently ask me the same question: “How many film crew members work on set compared to those working in post-production?” It’s a good question as it touches on a few interesting topics. Firstly, it speaks to the huge number of diverse jobs performed by people in the pursuit of making a film. Secondly, it gives us a way of looking at how the composition of film crews has changed over time. Finally, it gives new entrants to the industry a better idea of how many people may be on-set during a shoot.

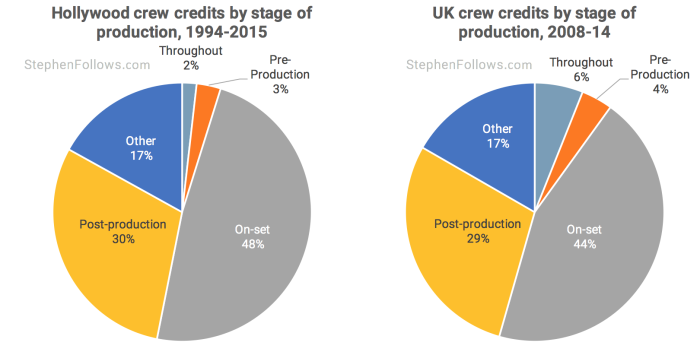

In order to answer the question I built two datasets – all films shot in the UK (2008-14) and top 100 US-grossing films of each year (1994-2015) – and looked at the number of people in each department on each film. I removed films which were entirely animation of visual effects (VFX) as I feel that this question relates to traditional “on set” filmmaking, which doesn’t apply to animation or VFX-only films. In summary…

- Across all Hollywood films, 48% of film crews work on-set

- Post-production crew outnumber on-set crew on films budgeted over $100 million

- UK films have a larger percentage of post-production crew, compared to Hollywood films of the same budget.

- Post-production crews are getting larger and are currently similar in size to on-set crews.

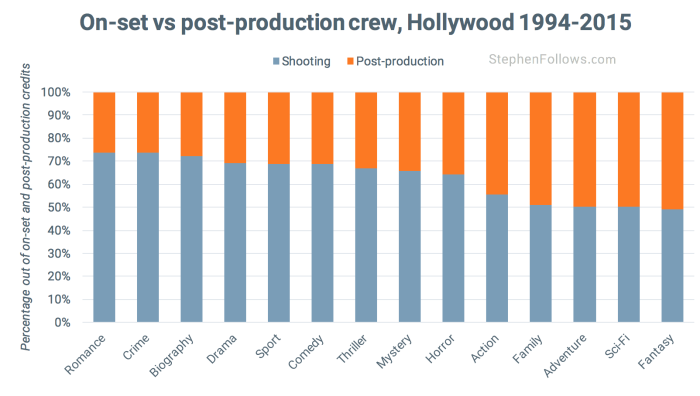

- On romantic and crime-based films, the ‘on-set’ crew outnumber the post-production crew three to one.

Shoot first, Post second

I grouped all of the film crew credits on my two sets of films into five broad “stages” of production…

I grouped all of the film crew credits on my two sets of films into five broad “stages” of production…

- “Throughout” which relates to jobs which are needed throughout the production, such as Director and Producer.

- “Pre-Production” jobs are those in which most of the work is complete before the shoot, such as Casting Director and Writer.

- “Shooting” roles are those whose main role is to be on set, helping the film get shot, such as Director of Photography and Stunts Performer.

- “Post-Production” covers roles involved with taking the footage shot on set and turning it into a finished article, such as Editor and Composer.

- “Other” is a catch-all for the small number of leftover roles which don’t neatly fit into the other four categories, such as Unit Publicist or Production Accountant.

At first glance it seems that ‘On-set’ crew make up the majority of a film crew on both Hollywood and UK films (48.3% and 44.5% of film crew, respectively).

Note: Throughout this article I’m using the phrase ‘Hollywood films’ to refer to the top 100 US-grossing films of each year. One or two may be indie films and some studio films released each year will have bombed and therefore not make this list. However, the shorthand of referring to them as ‘Hollywood’ films, as opposed to ‘UK films’, makes it easier to read so I hope you’ll excuse the generalisation.

As we often find when studying the film business, the industry-wide average gives a misleadingly simple answer. Therefore, I have split the films up by three criteria (year, budget and genre) to take a closer look.

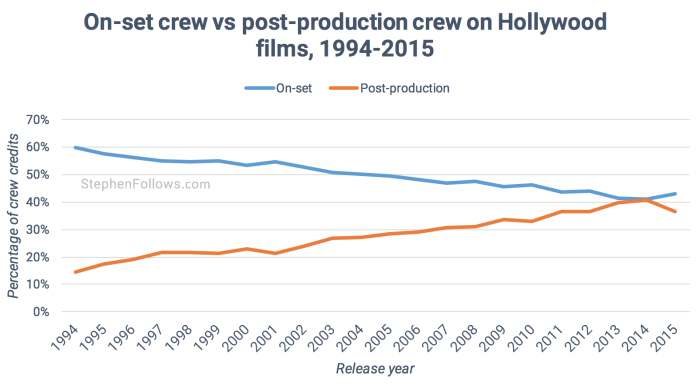

The post is starting to mount up

Arguably, the sector which has seen the biggest technological changes over the past few decades is Post-Production. The processes involved in taking a film from the shoot to the final product has moved from being extremely physical (exposing film, cutting, splitting, etc) to almost entirely digital (digital footage, computer visual effects, digital deliverables, etc). There’s no doubt that digital technology has also affected the cameras used on set, but the rest of the technology has changed little (such as lenses and grip kit) and the workflow of how a film set runs is very similar.

Arguably, the sector which has seen the biggest technological changes over the past few decades is Post-Production. The processes involved in taking a film from the shoot to the final product has moved from being extremely physical (exposing film, cutting, splitting, etc) to almost entirely digital (digital footage, computer visual effects, digital deliverables, etc). There’s no doubt that digital technology has also affected the cameras used on set, but the rest of the technology has changed little (such as lenses and grip kit) and the workflow of how a film set runs is very similar.

This is reflected in the employment statistics, with post-production taking an ever-larger share of the film crew credits.

The money’s in the post

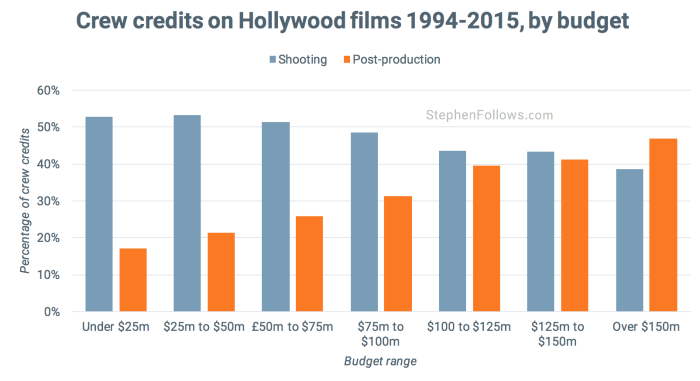

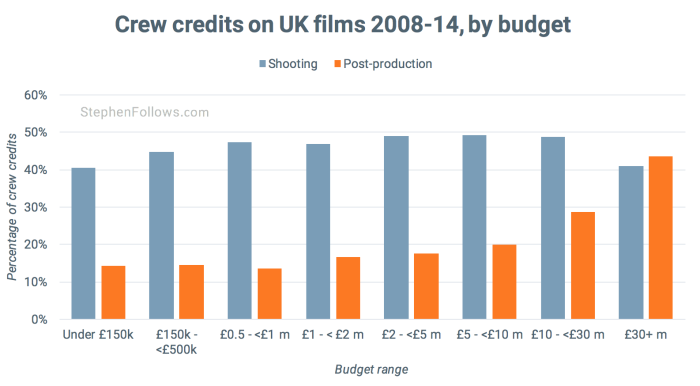

As budgets increase, so do the relative size of their post-production teams.

This trend is also found on UK films.

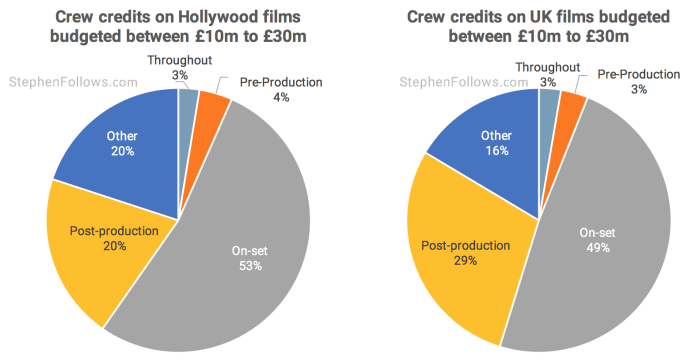

It’s interesting to note that UK films have a larger share of post-production crew than Hollywood films of a similar scale. I compared the data for UK films budgeted between £10m and £30m with Hollywood films on the same budget range (i.e. budgeted between $13.9m and $41.6m) and found that 28.8% of the UK film crew were in post-production, compared with just 20.3% of the Hollywood film crew.

The UK is often celebrated as boasting many of the best visual effects houses in the world, thanks in part to the UK tax credit rewarding projects financially for doing VFX work in the UK and the Harry Potter films for incubating and supporting so many VFX crew members.

Romance is on-set, Fantasies happen afterwards

As one might expect, the films which relate more to spectacle, such as Sci-fi and Fantasy films, require a larger number of post-production crew.

The UK films showed pretty much the same results.

Notes for film crew research

Here are a collection of notes relating to today’s research…

The films – Today’s research looked at live action feature films shot in the UK between 2008 and 2014 inclusive (referred to as “UK films”) and the top 100 US-grossing films of each year between 1994 and 2015 inclusive (referred to as “Hollywood films”). 100% of the Hollywood movies and 93% of the UK films have IMDb listings, and so it’s those films I studied. I excluded animation or visual effects-only productions, but included films which mixed either with live action (such as Paddington, which is a live action film but the lead role is entirely CGI). The raw list of films came from the BFI and then I updated and added to it. I then used public sources (mostly IMDb) to determine how many people worked on each film.

The films – Today’s research looked at live action feature films shot in the UK between 2008 and 2014 inclusive (referred to as “UK films”) and the top 100 US-grossing films of each year between 1994 and 2015 inclusive (referred to as “Hollywood films”). 100% of the Hollywood movies and 93% of the UK films have IMDb listings, and so it’s those films I studied. I excluded animation or visual effects-only productions, but included films which mixed either with live action (such as Paddington, which is a live action film but the lead role is entirely CGI). The raw list of films came from the BFI and then I updated and added to it. I then used public sources (mostly IMDb) to determine how many people worked on each film.- Cast – The cast members are not included in film crew counts.

- Dates – The Hollywood years relate to the year of first US theatrical release, whereas the UK film years are production years.

- Overlap – I have measured film crew sizes by department, rather than via individual jobs. This means that there can be a little bit of overlap – such as the visual effects crew who are on-set taking measurements or the input a cinematographer may give in the grade. As we’re looking at a huge number of credits, I think that even if we could track these spillovers, they wouldn’t change the overall trends shown above.

- Time served – My numbers take no account of the length of time each person worked on the production. This means that a rigger who worked on set for one day, or a VFX artist working on one shot will receive the same weighting as the cinematographer or director.

- Seniority – My research is inadvertently Marxist, offering each person equal status to another. Anyone who has been on a film set will know that they are run more along the lines of Stalin than Marx. Consequently, we cannot infer that the bigger departments are more important. We can simply say that they had more people credited to them.

- Self-Reporting Bias – The credits for films on IMDb are submitted by production companies, studios, the public and some chap in a pub called Bernard; i.e. anyone can suggest a credit. IMDb requests evidence from the submitter and larger films can verify their credits as complete but this cannot completely eliminate the nature of self-reporting data being naturally skewed towards those who are the most proactive / self publicising.

Epilogue

The number of people who work on a feature film remains a very popular subject on this blog and in the questions I receive from readers. I think it’s something to do with the tangibility of the question and yet how hard it is for people to guess. Hopefully, today’s research will help shine a little bit more light onto the topic.

Comments

Thank you for this number approach.

Would it change a lot the results if you would have consider person/days working on the film ?

As a better reflection of the reality, which is what we can feel every working day.

Thanks again

‘Days worked’ would be a great way to analyse this. Every shoot – large or small – has busy ‘big set pieces’ days where there may be 200 people working on set. Yet on other days it may be a skeleton crew. I watched Director of Photography, Roger Deakins set up a crane shot for one of the last Bond movies, and – apart from a single security guy having a cuppa, (this was late in the evening in the city of London) there didn’t appear to be anyone else there! Obviously there must have been, but god knows where. I recall the scene from the movie, (007 drives up, steps from car and heads towards the entrance to a Hong Kong’ skyscraper). So, one could get away with shooting this with 10 crew, (Roger, an assistant, a couple of grips, a driver, two on sound and one location manager. Throw in a Director and a runner and you’ve got your ten). However, shoot it mute, (highly likely) and have Roger direct the scene (again highly likely) and you can whittle this down to 6. My point is, days vary tremendously, So ‘days worked’ is definitely a great approach.

And a very interesting topic, for which you need the statistics. However, my bet is that most readers want to come away with actual numbers rather than percentages, so examples along the lines of on-set crew for, say, Terminator II, was X on a busy day and Y on a quiet day. Compared to a low budget ‘Indie’ movie, say, 24 Hour Party People, where X and Y will differ. (the former will swing wildly whereas the latter won’t).

How you go about collating ‘days worked’ is an entirely different matter! Film budgets won’t tell you, (and besides, they lie). All producers like to inflate the cost of their movies, so little help there, (and besides, they won’t know). Unless there’s a resource I don’t know about, then the only accurate way is to ask a Line Producer. In association with the production manager, they will have originated the scene breakdown, shoot schedule and daily crew allocation. So find yourself some friendly faces, pick a bunch of shoots that are historical enough not to make them nervous and – good luck!