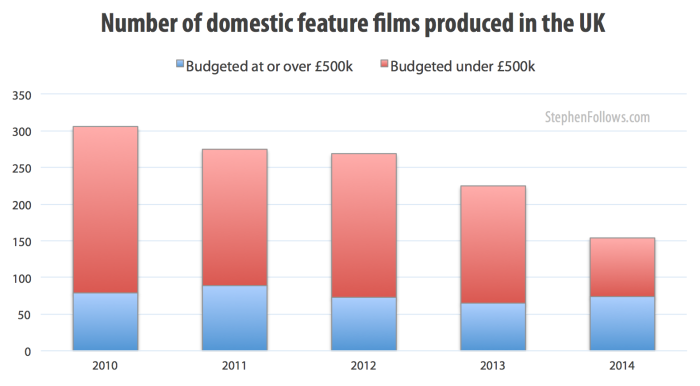

Today’s article is looking at the recent decline in the number of films being made in the UK, specifically the dramatic fall in low-budget film productions. Every year the BFI publishes a Statistical Yearbook, which is a collection of facts and figures about the UK film industry. For the fourth consecutive year, they have recorded a fall in UK film production and the number of films being made on under £500,000 has fallen by 50% between 2010 and 2014.

Today’s article is looking at the recent decline in the number of films being made in the UK, specifically the dramatic fall in low-budget film productions. Every year the BFI publishes a Statistical Yearbook, which is a collection of facts and figures about the UK film industry. For the fourth consecutive year, they have recorded a fall in UK film production and the number of films being made on under £500,000 has fallen by 50% between 2010 and 2014.

In order to work out what’s going on with low-budget film, we need to define what types of films are made in the UK…

- Inward Investment – Films which are substantially financed and controlled from outside the UK. They shoot in the UK because of …

- Script requirements (eg locations); and/or

- The UK’s filmmaking infrastructure; and/or

- To access money via the UK film tax relief.

- Co-productions – Films made across two or more countries whereby the film has multiple nationalities (i.e. the film is officially both a British film and a French film).

- Domestic – These are films produced by a UK production company and made wholly or partly in the UK. This is the type of film which has experienced a sharp decline in production in the past few years.

Inward investment

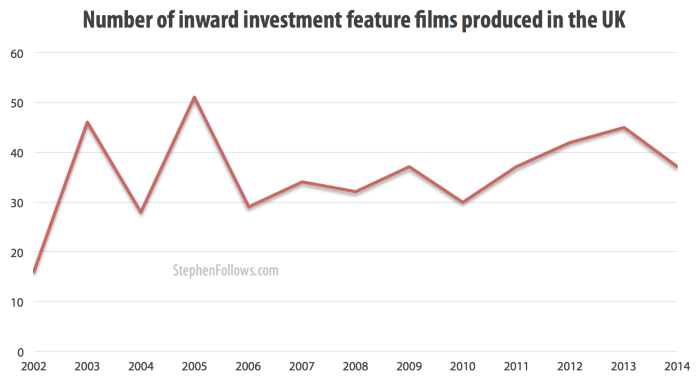

Thanks in part to the popular UK Film Tax Credit and to the quality of UK crew and facilities, the UK has seen a steady growth in inward investment films. The majority of these are American films from Hollywood studios, although in the past there have been a number of projects from India. In 2014, 17 out of the 37 ‘inward investment’ films had budgets of over £30 million.

Thanks in part to the popular UK Film Tax Credit and to the quality of UK crew and facilities, the UK has seen a steady growth in inward investment films. The majority of these are American films from Hollywood studios, although in the past there have been a number of projects from India. In 2014, 17 out of the 37 ‘inward investment’ films had budgets of over £30 million.

In 2014, inward investment only accounted for 17% of the films shot in the UK, up from 14% in 2013. However, more than four out of every five pounds spent on film production in the UK comes via inward investment (81% of total spend in 2013 and 84% in 2014).

Co-productions

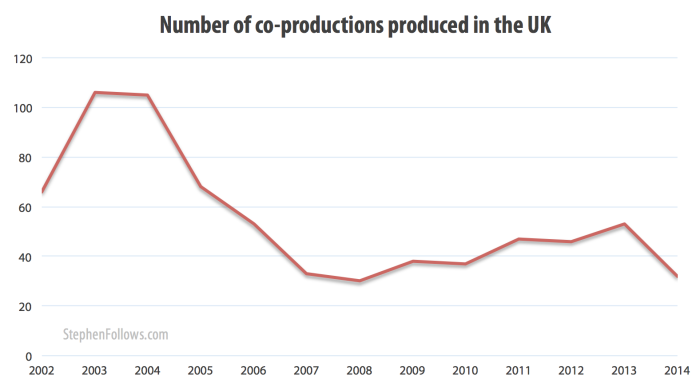

Co-productions are a method by which filmmakers can have their film officially classed as having multiple nationalities in order to access funding and tax benefits from more than one country. Co-productions are only possible if the two countries involved have a bilateral treaty (the UK currently has treaties with Australia, Canada, China, France, India, Israel, Jamaica, Morocco, New Zealand, the Occupied Palestinian Territories, South Africa and is soon to be signing one with Brazil) or if both countries are signed up to the European Convention on Cinematographic Co-production.

Co-productions are a method by which filmmakers can have their film officially classed as having multiple nationalities in order to access funding and tax benefits from more than one country. Co-productions are only possible if the two countries involved have a bilateral treaty (the UK currently has treaties with Australia, Canada, China, France, India, Israel, Jamaica, Morocco, New Zealand, the Occupied Palestinian Territories, South Africa and is soon to be signing one with Brazil) or if both countries are signed up to the European Convention on Cinematographic Co-production.

Co-productions have declined sharply in the UK since a change in the law which limited the amount co-productions can claim back via the UK Tax Credit to a percentage of the UK spend, not the whole budget. In 2014, co-productions accounted for 14% of films made in the UK.

Domestic films

All films shot in the UK contribute to the UK film economy but when most people use the term “the British film industry” they normally are referring to domestic UK films. These are films made by UK productions companies, largely financed by private individuals and without support from Hollywood studios.

All films shot in the UK contribute to the UK film economy but when most people use the term “the British film industry” they normally are referring to domestic UK films. These are films made by UK productions companies, largely financed by private individuals and without support from Hollywood studios.

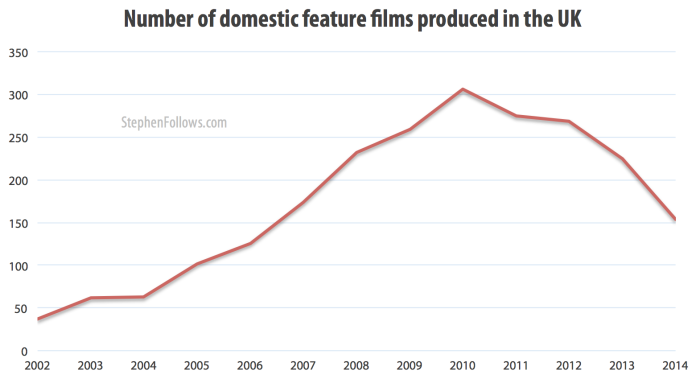

Between 1994 and 2010, UK domestic production increased ninefold, from 33 films in 1994 to a staggering 306 films in 2010. This was in part due to a dramatic fall in the cost of making a feature film and to the increase in the level of government funding available, via the UK tax credit and its predecessors. (Another factor is the support given by Lottery-funded bodies such as the UK Film Council, the BFI and regional screen agencies but it’s hard to be able to pinpoint what impact they have had on production levels).

The decline of the past four years

Between 2011 and 2014, the number of domestic UK films has fallen by half, from 306 in 2010 to 154 in 2014. Almost all of this decline has been limited to films budgeted under £500,000.

What’s happening to low-budget film production?

To be honest, I’m not sure. The decline could be down to a number of factors.

The first of which is underreporting. Today’s figures come from the BFI who do a marvelous job tracking UK film productions and each year they publish a review of the previous year’s figures via their Statistical Yearbooks (i.e. the 2015 Yearbook contains the figures for films shot in the UK during 2014). There is no legal requirement for filmmakers to inform the BFI of their production and so the BFI has to use a number of sources to generate these numbers. In many cases, the first the BFI hear of a film is when the production company applies for tax relief via the Cultural Test, which can only happen after the film is complete.

The first of which is underreporting. Today’s figures come from the BFI who do a marvelous job tracking UK film productions and each year they publish a review of the previous year’s figures via their Statistical Yearbooks (i.e. the 2015 Yearbook contains the figures for films shot in the UK during 2014). There is no legal requirement for filmmakers to inform the BFI of their production and so the BFI has to use a number of sources to generate these numbers. In many cases, the first the BFI hear of a film is when the production company applies for tax relief via the Cultural Test, which can only happen after the film is complete.

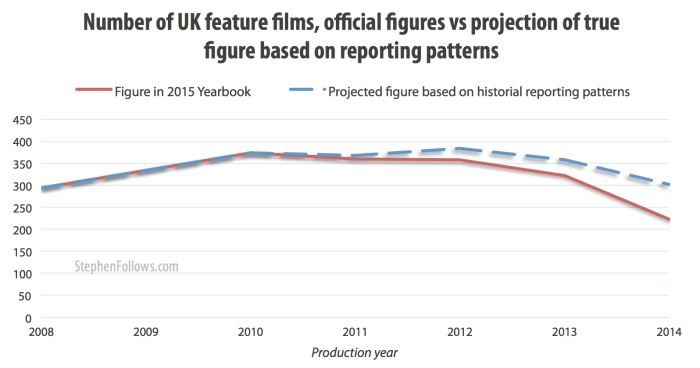

This means that with each new edition of the annual Yearbook, the BFI revise their figures from previous years. For example, the 2011 Statistical Yearbook listed 275 films as having been shot in the UK in during 2010 but by the time the 2015 Statistical Yearbook had been published, the 2010 production figure had risen to 373 films. I took a look at the changes in production data for the past five years and found…

- Across all films shot in the UK, the figure for the previous year’s production levels (i.e. the 2010 data in the 2011 Yearbook) only includes 74% of the films which will eventually be attributed to that year (i.e. the 2010 data in the 2015 Yearbook).

- For domestic films budgeted over £500,000 93% are listed in the following year.

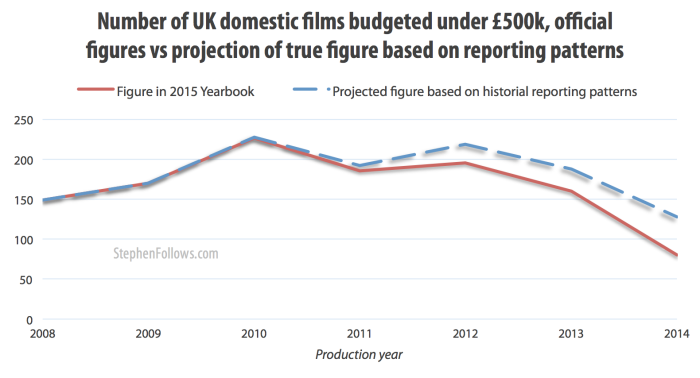

- For domestic films budgeted under £500,000, the films listed in a new Yearbook for the previous year account for only 64% of the films which will eventually be tracked.

So, if the current pattern continues then we should expect the official count of the number of films made in the UK in recent years to be revised upwards in coming Yearbooks. Using the historic patterns, I have projected how the production data for 2008-14 will look in the fullness of time.

And this underreporting is most acute in low-budget film, due to the challenges in finding these productions before they are distributed, screened at film festivals or apply for their tax rebate upon completion.

(This all leads to a philosophical question… If a micro-budget film shoots in the forest but there’s no-one there to distribute it, is it really a film…?)

So even when we take into account underreporting, low budget film in the UK have experienced a sharp decline, from 307 in 2010 to 216 in 2014 (both projected figures, as detailed above). Other reasons could include…

- A regression to a more ‘normal’ level after an unsustainable boom caused by the financial crisis. It has often been said that the film industry is recession proof as when consumers have less money to spend they reduce their consumption of expensive goods and rely more on cheaper entertainment, such as movies and television. Further more, the recent financial crisis saw a number of previously well paid individuals being forced to find new careers. (Anecdotally I have heard from a number of UK film training providers that demand for introductory film training increased after the financial crisis). So one could make a case that the recent boom in filmmaking was caused by a perfect storm of new tax rules, the proliferation of high-end digital filmmaking equipment and increased funding from high net worth individuals who were looking to start a career in filmmaking.

- It’s a generational thing. Making a feature film used to be much more of an achievement than it is today. The generation of filmmakers who learnt on celluloid film (I count myself among this group) have regarded the recent shift to professional digital filmmaking as a chance to finally achieve the previously-unachievable goal of making a feature film. They ran out in their hundreds and shot everything that moved. However, the next generation of filmmakers grew up in the digital revolution and so making a feature film is less of an achievement. The turnover in filmmakers is quite high, as I’ve shown before, with only one out of five feature filmmakers making a second film. This means the people producing feature films in 2010 are a very different group of people to those producing features in 2014.

- The increase in aspirational alternatives to making a feature film. The route into filmmaking used to be fairly linear – small short films lead to larger, funded short films which hopefully lead to features. Feature films were the main goal as there were few aspirational alternatives. However currently many filmmakers are making content directly for the web (web series, vlogs, comedy sketch series, etc) or being drawn towards a career in television by the recent trend of high-end epic series (such as Game of Thrones, House of Cards, etc).

- The glut of films caused an over-supply, meaning that more recent films have a harder time securing finance. In the past decade, the number of films available to film buyers has massively increased (727% times in the UK between 2002 and 2010) whereas the demand from consumers has not grown by an equivalent amount (over the same period UK cinema admissions shrank by 4%, from 176 million in 2002 to 169 million by 2010). This means more films are not able to secure distribution and therefore their investors are not repaid. The films shot during the boom in 2010 would have been approaching investors in 2008 and 2009, using recoupment data from films released in the previous ten years or so. This would have painted a much rosier picture of film investment than the figures filmmakers who shot in 2014 had to work with.

But these are just my theories. I am keen to hear what readers think about this recent decline. Feel free to leave a comment below or contact me directly.

Epilogue

It should be noted that a decline in the number of feature films being made is not necessarily a bad thing. Many industry professionals felt that the recent boom in filmmaking was harmful to the industry as it flooded an already crowded market and hurt the image of film as a viable investment. In addition, many of the films made on the smallest budgets involved people working for free and/or in unprofessional environments.

Personally I don’t see an increase or decrease in UK film production as inherently good nor bad. I think it’s important that our industry is inclusive and allows people from all backgrounds to get involved if they want. There’s no doubt that too many films being made is harmful to the industry but I like to think that the industry is more accessible than in the 1990s where feature filmmaking was the preserve of the connected, the rich and the crazy.

Comments

really good article and i think you have captured some really strong data. I agree with all your theories and think that we are in a era where there is a mix of unreporting of very low budget films that never bother or need to get the attention of the BFI. There is also a developing VOD market that again means for some low budget filmmakers they work in an environment of crowd funding and sponsorship and self or hybrid distribution that keeps them under the radar.

Another good article, Stephen. I agree with your footnote that more films is not necessarily a good thing. The creation of quality films is a better signifier of the strength of UK production.

Underrepresentation is a significant factor. I am contact with many micro-budget filmmakers whose projects slip entirely under the “official” radar. in 2002/3, I myself shot a comedy feature in the forest (the New Forest to be precise), which won an award in a New York film festival and received US and UK DVD release. It was still not registered by BFI et al.

There is also an argument that the UK does not really have a UK film production industry, but it does provide film services to the film production industry as a whole. Whatever home productions are created are done in a “cottage industry” fashion i.e. not a scaleable business/commercial model.

Very interesting, I am trying to get my head around all of this. I believe it is a generational thing most of all, the digital boom of film making, then a decline due to the lack of profit made from the boom films.

Crowdfunding was huge in 2008 (when everyone jumped on the bandwagon) but then crowdfunding got over saturated, if your not famous online making money from crowdfunding is too difficult – it is not the go to option for low budgets anymore.

There was also this romantic idea that you make a film, send it to sundance and then your a film director. There will be a huge increase in festival submissions in 2008 and i bet it is starting to decrease now. Yes anyone can make a film these days but perhaps recognition is still only reserved for the connected,the rich or the crazy.

–

(some more thoughts – )

The decrease in cinema attendance is only 4% since 2002 – I am surprised I thought it would have been much more. Also films lie about their budgets constantly, a few years ago I worked on a 500K film that claimed to be made for 3million. Quality over quantity every time – I feel a decrease of low budgets is a very good thing.

Really interesting, Stephen. Perhaps as with the Chinese general, answering a question on the effect of the French Revolution on the modern word, “it’s too early to tell”.

I agree with your piece and the contributions above. I think the mix of difficulties with breaking into an inner elite circle, crowdfunding limitations and the stamina required to run a successful dog and pony show and festivals and trade fairs may exhaust inexperienced creatives who may choose other media for getting across your message.

Also – given the technological revolution in filmmaking in the last decade – it would be interesting to learn how the BFI defines the concept of a “feature film”. What criteria does a creative moving image work have to fulfil in order to be included in the BFI figures? It would also be good to know if there has been any shift in this definition over recent years.

Also, if availability for theatrical release is one criterion, the number of UK cinema screens – and the percentage of these screens prepared to show domestic feature-length movies – could also be factors.

This has all come about for one reason and one reason only – piracy.

It is killing films but has a great effect on low budget films than any other sector. In the old days you could roll a film out for 12-18 months. Now once it is released in one country it is released everywhere online. Distributors in other countries know its not worth releasing them no master how good as sales will be poor. Broadcasters globally are not buying many of these films anymore.

Every young filmmaker I have ever met pirates films and they then wonder why there is no future for them.

We need to think of another way to ensure a return on investment. There is so much out there looking to invest in all manner of ventures. We crack the key to filmmakers/ distributors/ investors getting a return from illegal online screenings and we will once more have a vibrant industry.

I have to agree in part here with NDW in regards to the piracy issue. There seem to be hundreds of stream and torrent sites that once in possession of a title seem to rapidly share. I have felt the despair of trying to chase and shut down the loss of a movie at first hand. It’s a thankless and financially crippling process. What I think is needed, apart from a more vigorous and encrypted method of keeping our hard fought for work off these sites, is a simpler approach, and more business-knowledgeable processes of agreement tabled by filmmakers at sales contract stage. By this I mean ensuring that deals are signed with a specific release date that encompasses no more than 10 days or so between the first and last territorial release negotiated. That means essentially getting all your distribution deal ducks in a row. I noted from M Night Shayalaman’s last movie (love him or hate him) that producers had struck 26 territorial deals with no more than a 10 day gap between releases, first to last. And the releases were all platforms day and date. This methodology gives pirates very little time to impact a movies prime revenue-generating release period. Even pirating impact takes a while to get up to speed. But the impact can be minimized (if it cant be removed entirely). If sufficient numbers of end consumers have paid for a title through the myriad of platforms available, on or near to first release, there is little to pirate from. It’s not a perfect answer, and it won’t always be possible to regulate deals to release in such a manner, but if that process can be at the forefront of a producer’s mind at the deal table, fortune may smile. Of course there will seemingly always be infringements of some sort, as costly as they can be. But the financial impact of pirating can be limited if a filmmaker’s head is occupying the pre-emptive space. Just MHO.

M

Maybe 99% of indie films just plain suck.

I seriously doubt piracy has any ill effect, especially on indies. You’re lucky if your film is pirated to the point the world gets to see it. But that doesn’t happen. If it did you’d be a household name.

I believe Stephen hit on a number of valid reasons here, most especially the bubble of the indie industry in 2010 when the cost of HD hit a low point, and before the market became saturated with indie films. Sundance alone saw something like 12,000 film submitted in a recent year. No doubt most of them go nowhere, and their investors quit.

But another point no one mentions is the gatekeeper distribution model. Try to talk to a sales agent or distributor at Cannes, Berlin, or AFI in LA. You quickly find out what they’re looking for, which changes all the time, by the way. But they will instantly weed out 99% of the indies simply with the requirement of a named actor and/or producer and/or director.

What indie filmmakers seemed to have missed is that if you don’t have those things you’re off the grid and you have to self distribute. Build a website and drive traffic to it. Good luck. Nothing comes easy. Things take time. [insert your own bumper sticker saying here]

And so we a growth of YouTube and web series, even by named people. Because even the gatekeepers only want certain names and certain genres.

Of course you can find distributors that will take your film. Just don’t expect to see any profit after net expense. Don’t expect any kind of wide or cross markets release either. Basically they’re conning you out of your product to fill their slates. But you’re dumb enough to sign the contract with stars in your eyes. Hence no second time filmmakers.

But I think the good news is that the advance of technology will and has democratized the markets. A vast better and speedier internet will give the gatekeeper markets some stiff competition. Hasn’t happened yet. But it’s a different world. With so many players and so many channels, it’s like you need to find your niche market and play to it. On the other hand. maybe 99% of indie films just plain suck.

To respond to JR’s comment, I don’t think we can dismiss piracy so lightly. I recently edited a low-budget British genre film which had a limited theatrical release and sold very well on disc. However, the distributors found that from one illegal streaming site alone the film had been downloaded 600,000 times. Certainly we can assume that many of those people wouldn’t have downloaded the film if they had to pay for it, but it would have only needed 10% of those 600,000 to have paid for the film for it’s fortunes to have been markedly changed.

I have further thoughts on piracy, but I don’t want to stray too far off-topic.

Co-productions have declined sharply in the UK since a change in the law which limited the amount co-productions can claim back via the UK Tax Credit to a percentage of the UK spend, not the whole budget. In 2014, co-productions accounted for 14% of films made in the UK.