The film business is changing rapidly; arguably we’ve seen more change in the past decade than in any time since the rise of the Hollywood studios in the 1930’s. Films are now much easier and cheaper to make and distribute, meaning that the supply of films has risen sharply and we have numerous new ways of reaching consumers. However, so have the threats to the business of film, with online piracy denting sales, globalised word-of-mouth challenging traditional marketing and a growing impatience among consumers to politely wait for films to reach their country.

The film business is changing rapidly; arguably we’ve seen more change in the past decade than in any time since the rise of the Hollywood studios in the 1930’s. Films are now much easier and cheaper to make and distribute, meaning that the supply of films has risen sharply and we have numerous new ways of reaching consumers. However, so have the threats to the business of film, with online piracy denting sales, globalised word-of-mouth challenging traditional marketing and a growing impatience among consumers to politely wait for films to reach their country.

One of the most visible ways Hollywood is adapting to this changing world is in the timings of the films they distribute around the world. I’m 32 and I remember as a kid setting the VHS to record Box Office America at 2am on Monday nights. The half-hour show would present trailers for the films at the top of the cinema chart in America. The vast majority of the films would be completely new to me and I would have to steel myself to wait the many months before they would reach UK cinema screens. After waiting to catch it in the cinema I would then have another tedious wait to be able to rent it on VHS and a further year or so before I could buy it. However in 2015, many films open on the exact same day in the UK and US and it’s not long before they make their way to DVD and Video On Demand (VOD). I thought I would take a look at the numbers around this change and explain why this is happening. In summary…

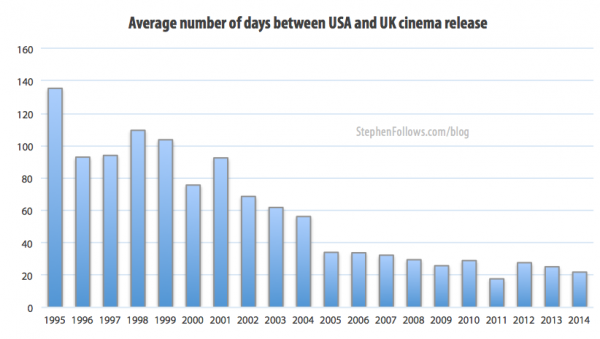

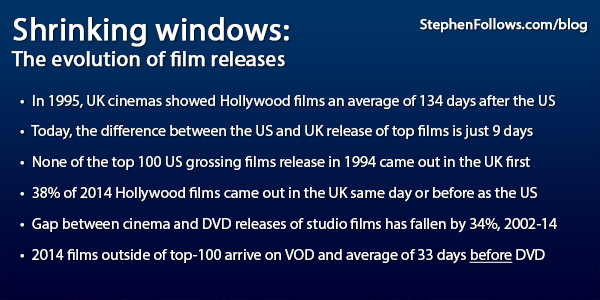

- In 1995, UK cinemas showed Hollywood films an average of 134 days after the US

- Today, the difference between the US and UK release of top films is just 9 days

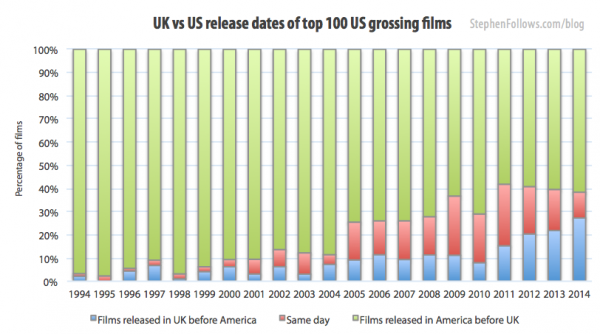

- None of the top 100 US grossing films released in 1994 came out in the UK first

- 38% of 2014 Hollywood films came out in the UK same day or before as the US

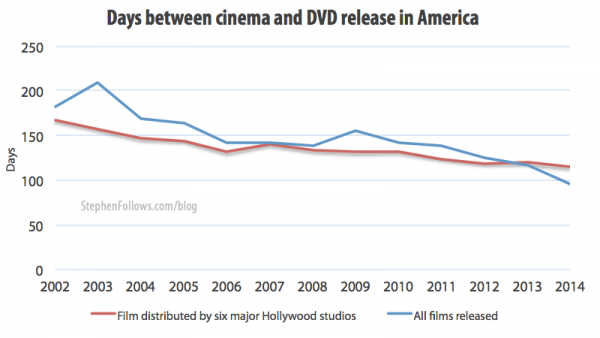

- Gap between cinema and DVD releases of studio films has fallen by 34%, 2002-14

- In 2014, films outside of the top 100 box office chart arrived on VOD an average of 33 days before DVD

Why are films released in cinemas at different times?

Historically, the principle reason for staggering a film’s release was physical – 35mm film prints are expensive and if you want to open in many places simultaneously then you’re going to need a larger number of prints. However, if you make fewer prints and travel those prints around, region by region, then you can save a great deal of money. Before the 1970’s the majority of Hollywood films used such a distribution strategy, known as a roadshow release. They would open in major US cities and then move around the country. The advantage of the first modern blockbusters, like Jaws and Star Wars, were that they showed Hollywood that a wide release (i.e. more than 600 screens simultaneously) had marketing benefits, and soon this became the standard.

Historically, the principle reason for staggering a film’s release was physical – 35mm film prints are expensive and if you want to open in many places simultaneously then you’re going to need a larger number of prints. However, if you make fewer prints and travel those prints around, region by region, then you can save a great deal of money. Before the 1970’s the majority of Hollywood films used such a distribution strategy, known as a roadshow release. They would open in major US cities and then move around the country. The advantage of the first modern blockbusters, like Jaws and Star Wars, were that they showed Hollywood that a wide release (i.e. more than 600 screens simultaneously) had marketing benefits, and soon this became the standard.

However, the international distribution of a film is much more complicated, involving third party distributors, differing local laws/ censorship and the need to “localise” films via subtitles or voice dubbing. In the days before instant international communication, such as Facebook and Twitter, it was much easier for Hollywood studios to keep non-US consumers in the dark about an upcoming film until they were ready to release it in their country. Plus, in English-speaking countries, it was often possible to use the same 35mm prints they had been screening in America for the past few months. Sure, they were a bit scratched and jumpy but consumers didn’t seem to notice.

How long would international cinema-goers have to wait?

As my 12-year-old self would have put it… “For evvvveeerrrr”. I took a look at the highest grossing films at the US box office of each year, to compare the local release date and the original US release date. In 1995, on average, Hollywood films came out in the UK four and a half months after America. Twenty years later that number has fallen from 134 days to just 22 days, a reduction of 84%.

As my 12-year-old self would have put it… “For evvvveeerrrr”. I took a look at the highest grossing films at the US box office of each year, to compare the local release date and the original US release date. In 1995, on average, Hollywood films came out in the UK four and a half months after America. Twenty years later that number has fallen from 134 days to just 22 days, a reduction of 84%.

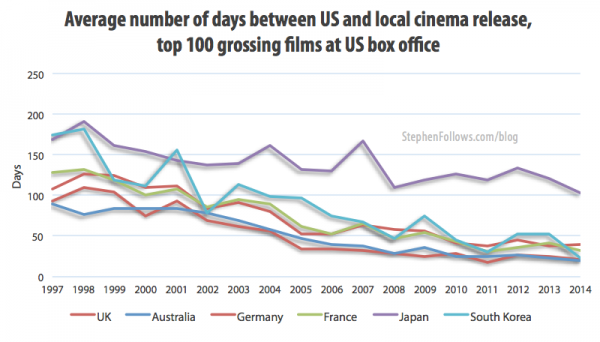

UK cinema goers in 1995 had to wait longer than consumers in Germany (117 days) and France (127 days), although not as long as the Japanese consumers (158 days).

Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery opened in America and Canada on 2nd May 1997, but South Koreans had to wait until 19th November 2000 to see it.

What percentage of films come out in the UK before America?

In 1995 none of the top 100 grossing films came out in the UK before America, but by 2014 one in three came out on or before the US release.

Is it different for Hollywood blockbusters?

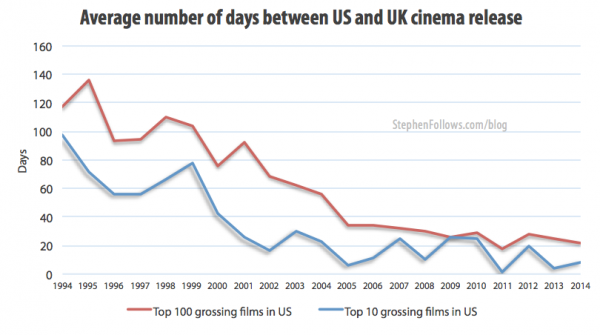

Yes, the largest films of each year have always come out slightly sooner in foreign countries than the rest of the top 100 films. In 1995, the average number of days between the US and UK release of the top 10 films (by US gross) was just 71 days, almost half the average for the top 100 films. Even today this trend holds, with the average for 2014 being 9 days for the top 10 films and 22 for the top 100 films.

Yes, the largest films of each year have always come out slightly sooner in foreign countries than the rest of the top 100 films. In 1995, the average number of days between the US and UK release of the top 10 films (by US gross) was just 71 days, almost half the average for the top 100 films. Even today this trend holds, with the average for 2014 being 9 days for the top 10 films and 22 for the top 100 films.

This trend holds true for all countries I have reliable data for. I can’t give a definitive list of reasons why this is but I would imagine that it has a large amount to do with the huge amounts of money that have been spent on the films, which the investors are keen to see returned. At an annual interest rate of 5%, an outlay of $300 million (cost of movie and marketing) would be accruing interest of around $40,000 a day.  An unusual example of an English-language film with a Hollywood star which was released late in America is Taken. The film was produced by French producers and was released initially in France in 27th February 2008. It opened in the UK on 26 September 2008 (almost seven months later) and finally in the USA on 30th January 2009, almost a year after the French release).

An unusual example of an English-language film with a Hollywood star which was released late in America is Taken. The film was produced by French producers and was released initially in France in 27th February 2008. It opened in the UK on 26 September 2008 (almost seven months later) and finally in the USA on 30th January 2009, almost a year after the French release).

What about the gap between cinema and DVD?

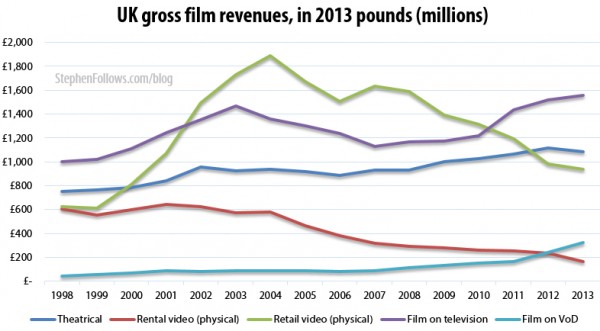

This is an entirely different story. The distribution of films has historically followed the same pattern of ‘release windows’, i.e. the window of time a film is available on a certain platform. Towards the start of the last century the only place consumers could see films was in cinemas. The 1940’s saw television becoming an additional income stream, proving invaluable in the late 1960’s to counter huge theatrical losses on big budget flops such as Cleopatra. In the mid-1970’s the “Home Entertainment” sector (i.e. renting and selling VHS tapes) started to grow. By 1986 ‘home entertainment’ generated more income than the cinema box office and in 1992 VHS sales alone surpassed cinema income. The modern era has introduced a plethora of new distribution outlets, mostly grouped under the banner “Video on Demand” (VOD).

Until a few years ago, almost every film on major release would follow the same pattern…

- Theatrical (i.e. cinema)

- Hotels and airlines

- Rental (VHS, DVD and Blu-ray)

- Retail (VHS, DVD and Blu-ray)

- Pay-Per View (PPV) and Video on Demand (VOD)

- Pay television

- Network television

- Syndication

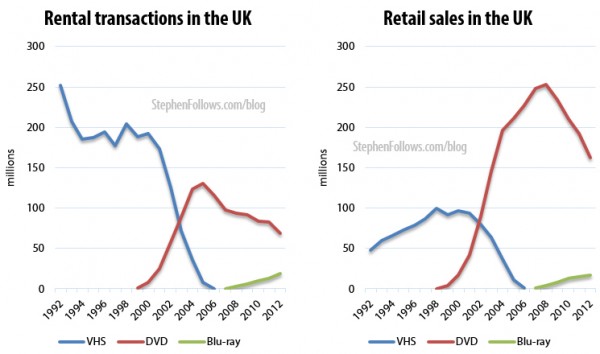

The first to go was the eight-week exclusive window for Rental. In the UK this was started by Warner Brothers in 2003, after a long battle with Blockbuster, who had refused to stock Warner tapes if they were available to buy on the same day they went on the rental market. Blockbuster backed down and the rental window quickly disappeared off the standard model of release windows.

The first to go was the eight-week exclusive window for Rental. In the UK this was started by Warner Brothers in 2003, after a long battle with Blockbuster, who had refused to stock Warner tapes if they were available to buy on the same day they went on the rental market. Blockbuster backed down and the rental window quickly disappeared off the standard model of release windows.

After the rental window was shrunk to nothing, the other release windows came under similar pressure. The studios benefit from reducing the time between each distribution method as they can pay for just one integrated marketing campaign. A film which is fresh in the minds of consumers will sell better and commands a higher price from television channels. The National Association of Theatre Owners tracks release windows for Hollywood studios. I performed my own research, looking at 3,995 films released in the US between 2002 and 2014.

The companies on the other side of the argument, mostly the cinemas, are not so pleased with the shrinking windows. Cinemas are expensive business to run and so they fight hard to protect their exclusive window. Having taken lessons from the fate of Blockbuster, cinema chains are digging their heels in and recent test cases have produced victories for each side.  In 2006 Odeon took a stand against Disney’s plan to release Alice in Wonderland on DVD just 12 weeks after it first opened in cinemas, rather than the traditional 17 weeks. At the time Odeon had 27% of the UK market, including 70% of the 3D screens so not screening the film would have hurt both Odeon and Disney greatly. At the very last minute, Odeon relented and the 12 week window remained. Three years later, cinema owners in the US were successful in halting Warner Brothers’ plans to release Tower Heist on VOD just three weeks after it opened in cinemas for the hefty price of $60.

In 2006 Odeon took a stand against Disney’s plan to release Alice in Wonderland on DVD just 12 weeks after it first opened in cinemas, rather than the traditional 17 weeks. At the time Odeon had 27% of the UK market, including 70% of the 3D screens so not screening the film would have hurt both Odeon and Disney greatly. At the very last minute, Odeon relented and the 12 week window remained. Three years later, cinema owners in the US were successful in halting Warner Brothers’ plans to release Tower Heist on VOD just three weeks after it opened in cinemas for the hefty price of $60.

What about VOD movie release dates?

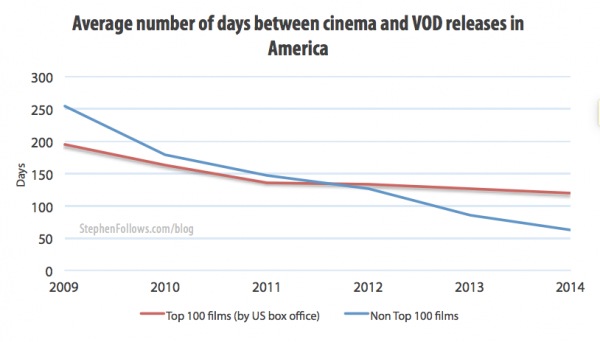

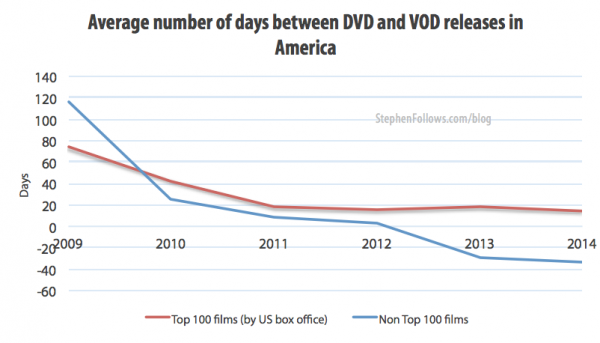

Most of the discussion within the industry focuses on the window between theatrical release (i.e. cinema) and home entertainment (i.e. DVD and Blu-Ray), however there is shrinking in other areas too. VOD movie release dates are harder to find than cinema movie release dates but I did manage to collect data on 1,480 films released between 2009 and 2014 (around two thirds of the films released). This includes 263 films from the top 100 of each year (i.e. 47%). The top 100 grossing films of each year have seen their cinema-to-VOD release window shrunk, from 195 days in 2009 to 119 days in 2014. However, films outside of the top 100 (i.e. largely independent, non-studio films), have seen a greater drop, from 255 days to just 62 days. This illustrates how VOD is fast challenging DVD for its supremacy in the third window of release.

Most of the discussion within the industry focuses on the window between theatrical release (i.e. cinema) and home entertainment (i.e. DVD and Blu-Ray), however there is shrinking in other areas too. VOD movie release dates are harder to find than cinema movie release dates but I did manage to collect data on 1,480 films released between 2009 and 2014 (around two thirds of the films released). This includes 263 films from the top 100 of each year (i.e. 47%). The top 100 grossing films of each year have seen their cinema-to-VOD release window shrunk, from 195 days in 2009 to 119 days in 2014. However, films outside of the top 100 (i.e. largely independent, non-studio films), have seen a greater drop, from 255 days to just 62 days. This illustrates how VOD is fast challenging DVD for its supremacy in the third window of release.

This means that in many cases films are available on VOD before they reach DVD. In 2014 the average number of days between the “third” window (i.e. DVD) and the “fourth” window (i.e. VOD) for a film outside of the 100 highest grossing films was minus 33 days!

Caveats and Notes

Data for today’s article came from a number of sources, including NATO (no, not that NATO), IMDb, MovieInsider, Opus / The-numbers, Box Office Mojo, Wikipedia, Rentrak, IHS, Attentional, British Video Association, Official Charts Company and the BFI. It has been hard to find full release data on films distributed in the pre-internet era. For the period 1994-2014, I found reliable release dates for the following percentage of films in each country…

- 95% UK

- 93% Australia

- 92% Germany

- 90% France

- 76% Japan

- 74% South Korea

I focused on these countries for my charts as they all fall in the chart of top ten film markets. I excluded the other top countries (China, India and Russia) as I could not find sufficient release data to make the results reliable. I also excluded Canada because the film industry sometimes includes it in the “North American” figures and sometimes treats it as an international territory. I found reliable Canadian release date data for 55% of my target films and I could not be sure if the remaining 45% were the same at the US (and therefore not reported) or just lost in the mists of time. This is a significant ‘unknown’ and so I opted to exclude them from my charts. Apologies to all Canadians, Canada-fans and mooses.

Epilogue

It was fun to research the data behind the vague memories I have as a teenage cinema fan. And if you’re a teenage reading this right now, feeling lost, unready for the world and out of the loop then don’t worry – maybe in 20 years you too will get to number-crunch your way to peace of mind. Stay strong (and practice your Excel formulae).

Comments

Stephen, as usual – great article! You’ve hit the nail on the head as to the reason for the same-date or similar date releases that now occur with expected box office mega films. And that nail is… piracy control as well as global marketing. Piracy is the main push for issues in Asia to my understanding, as the mass amount of theft left way too many box office tickets off the sales registers.

Not only does same-date release allow a studio to mount a major word-of-mouth AND social media (hey, it’s kinda the same) campaign around the film, matching advertising spend across all countries through traditional channels at well, it provides brand marketers a better ease to wrap their own marketing dollars around the film, and create a true co-branded marketing campaign around the specific launch period or targeted marketing period already alotted for the brand. A mobile phone partner that is going to release a new model isn’t staggering that release date in each country. Think of movies like Bond or Avengers… that mobile (or beer…or auto…or…) company is going to want shout from the tops of mountains NOW about the partnership, and not slooooowly push it out to market. In decades past, marketers would only concentrate on US marketing, as everything else was just too uncertain and spread apart. The movie studios are smart – they want to make everyone’s dollars better work for them.