48 trends reshaping the film industry: Part 1 Development and Finance

Each week over the last five years, I have been covering different aspects of the film industry, explaining and illustrating how they function. Next month, I'll carry on with my new research but for this month I would like to stop and zoom out a little.

By taking detailed data dives each week it's easy to miss the bigger picture and lose sight of the wood for the trees. So, for the next four weeks, I'm going to summarise the biggest trends and changes we've seen in the film industry recently.

To compile this list, I have been back through all of my old research, conducted new projects, read outside research and solicited suggestions from my industry readership (thank you to everyone who contributed). The result is a list of 48 trends and changes affecting the film industry. For readability, I have split them into four groups:

Development and finance (published today)

Each article will contain twelve trends, changes or shifts in the industry, along with a single chart to illustrate the point. Regular readers will know that limiting myself to just one chart per article will be a challenge and so I will also include links to more charts on the topic.

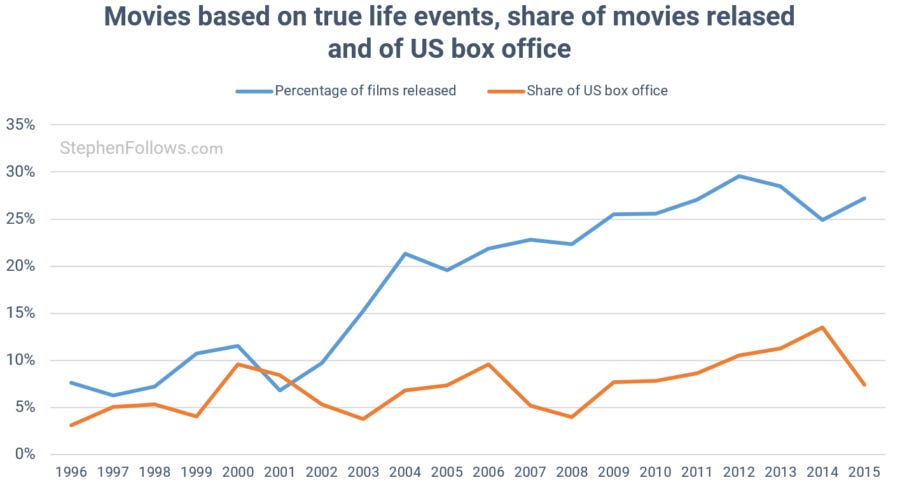

1. An increasing number of movies are being based on real-life events

Under 7% of movies in US cinemas in 1996 were based on real-life events. Twenty years later, that figure stood at 27%. Despite this nearly fourfold rise in real-life inspired film production, box office revenues did not keep pace.

The reason for this disparity is that the large increase in real life movies has mostly been in lower-budget filmmaking, with only 2.9% of movies budgeted over $100m being based on actual events (including Deepwater Horizon, Alexander, Pearl Harbor, The Perfect Storm, The Aviator, Ali and American Gangster).

Within fiction, drama movies have the highest share of real-life events. Interestingly, romantic comedies are the major genre least likely to be based on real life. This could be an example of just how unrealistic Hollywood’s standards are for romance, or it could be illustrating the desire for escapism among fans of the romantic genre. The rare exceptions include Becoming Jane, which is based on the life of Jane Austen.

My research also discovered that Indian and Japanese filmmakers are the least likely to base their movies on real-life events, with Israeli and German filmmakers being the most likely.

Further reading: How many movies are based on real-life events?

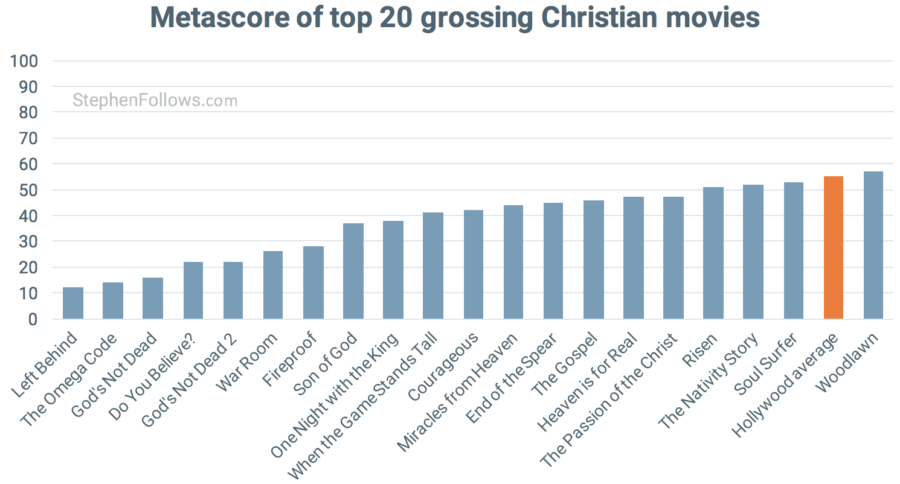

2. Faith-based movies have become hugely profitable, despite lacking mainstream appeal

Some of the most profitable films of the past decade have been movies made by and for American Christians. The Passion of the Christ led the way, grossing $612 million on a $30 million budget (2,040% box office to budget ratio) but it is far from alone.

There have been a string of successful Christian films which most mainstream film fans will never have heard of. These include God's Not Dead (3,132% box office to budget ratio), War Room (2,260%), Courageous (1,381%) and Heaven Is for Real (844%). It's worth noting that these films will also have performed very well on Home Video and VOD, adding to their total profitability.

Despite their massive returns, mainstream audiences have largely avoided the films and traditional film critics have been less than kind. The LA Times described War Room as a "mighty long-winded and wincingly overwrought domestic drama". Another critic noted that the film "might also have been better if it wasn’t shot like a term-life insurance infomercial". A third complained that the film was "so heavy on broad pulpit pounding that it’s challenging to get swept along by the story’s message".

The average Metascore for the top 20 grossing faith-based films is just 37 out of 100. For comparison, the average Metascore of the 2,000 highest grossing films of the past twenty years was 55

Despite the poor reviews, these films made huge amounts of money, thereby proving the power of connecting with a niche audience and ignoring the traditional industry's sneers.

In the course of conducting my research into faith-based films, I was fortunate to be able to record an interview with Stephen Kendrick, writer and producer of many of the highly successful Christian films that have recently been released. His movies have a combined budget of $6m and so far have grossed over $150m in US cinemas alone. You can hear that interview here.

Further reading: The Ascension of Christian films and What types of low-budget films make the most money?

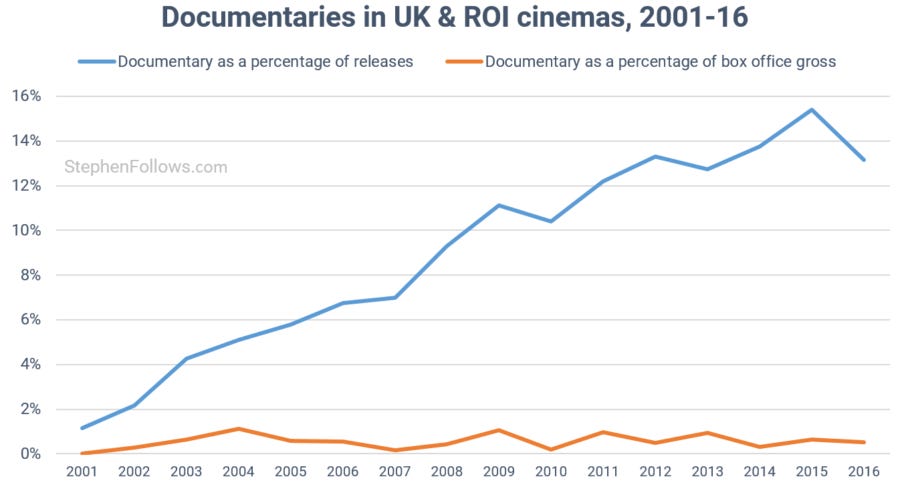

3. Documentaries are making up a higher percentage of movie releases

At the start of the new century, just four documentaries were released in UK cinemas. Sixteen years later, that number has ballooned to 108, accounting for 13% of all movie releases hitting the big screen.

Despite the dramatic increase in volume, the box office returns for documentaries are not impressive. They accounted for 13% of 2016 cinema releases, but just 0.5% of the overall UK box office revenue.

Further reading: How successful are UK documentaries in cinemas?

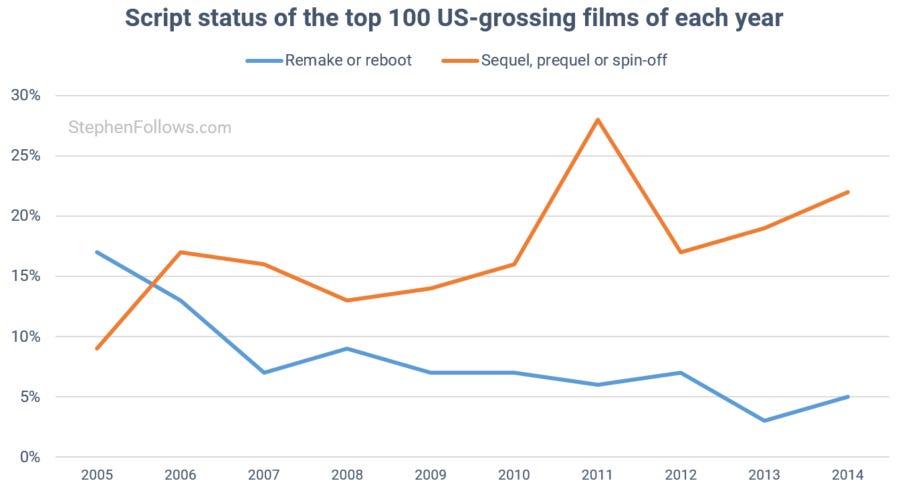

4. Hollywood is making fewer remakes and reboots (but more prequels, sequels and spin-offs)

Readers may be surprised to hear that remakes and reboots are accounting for fewer of the top grossing films than they used to. That's not because Hollywood is suddenly embracing one-off movies, but rather because their place is been taken by other derivative formats - namely prequels, sequels and spin-offs.

My research into the topic revealed that very few Hollywood dramas or romantic comedies are remakes (2.7% and 3.4% respectively during 2005-14). Other genres are more likely to feature remakes, such as horror. In fact, the fourth ever horror film (1897's The Haunted Castle) was actually a remake of the first ever horror film (1896's Le Manoir du Diable).

Further reading: The scale of Hollywood remakes and reboots and Hollywood sequels by the numbers

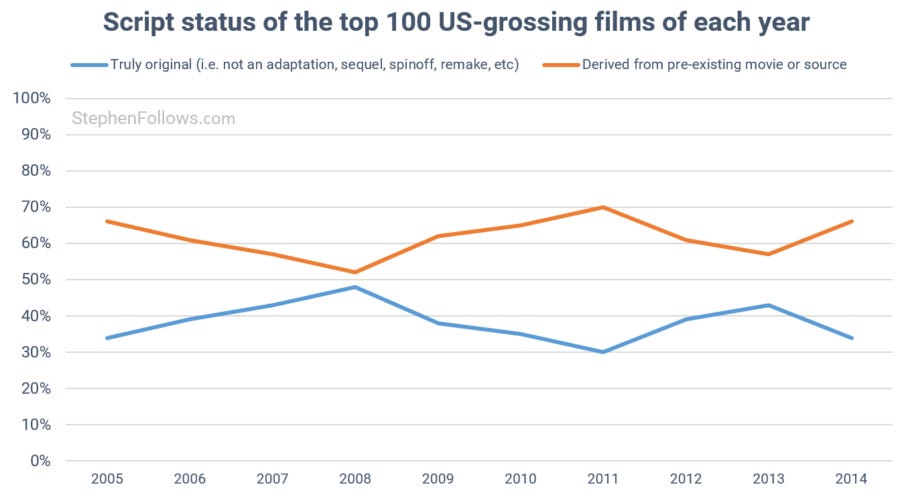

5. Hollywood films are becoming less original

Between 2005 and 2014, just 39% of the top 100 grossing movies were original (defined as a movie not directly adapted from an existing work, and not a sequel, prequel, spin-off, remake or reboot). It's worse at the top, with just 15% of the top ten grossing films in each year over that period passing this originality bar.

I should note that my use of the term 'original' here relates to whether or not a movie was a direct adaptation of existing material. This is different from the "Original Screenplay" term which awards such as the Academy Awards use. The awards definition is very broad and would mean that Fast and Furious 7, Saw IV, Final Destination 5, A Good Day to Die Hard, The Expendables 3, Rio 2 and Evan Almighty are all "original".

Although my definition of "original" does get closer to measuring the ubiquity of unique works than the Oscars' definition, it cannot take into account the true originality of the creative content. For example, the highest grossing ‘truly original’ film on my list is Avatar, which has often been accused of being an amalgam of existing tropes. The Boston Globe reviewer Ty Burr elegantly pointed out in his review of the film “In terms of plot, then, this is “Dances With Wolves.’’ Seriously: It’s the same movie, re-imagined as a speculative-anthropological freak-out“.

Further reading: How original are Hollywood movies?

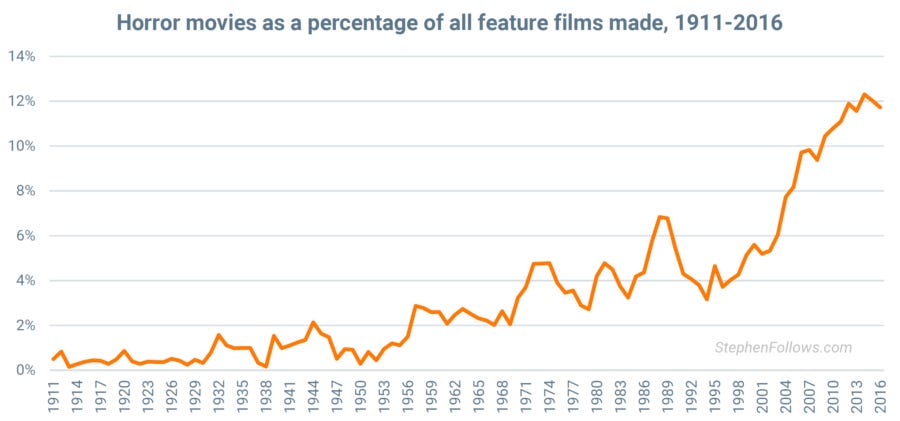

6. We're in a horror movie boom

In 2017, I published a long report into the horror genre, entitled The Horror Report. One of the most interesting findings was the increase in the number of horror movies being made.

Across all genres, film production levels have been increasing, but none faster than horror. In 2016, 1,028 horror movies were produced – twice the number made in 2006 (and the 2006 figure was almost four times more than the 1996 figure).

As well as the sheer number of horror movies increasing, horror represents an increasingly large proportion of movie production. Twenty years ago, horror movies accounted for 4% of all movies made, in 2016 they represented 12%.

This is likely to be due to a number of factors, including:

Technological changes have made filmmaking cheaper and more accessible. Horror films thrive on low budgets because they can be created with minimal outlay and horror audiences are very forgiving of cheap effects. As the technologies for shooting, editing and distribution reduced in price, the number of horror films increased.

Horror has lost some of the stigma it had in the past. In the past, many studio heads and movie marketers regarded horror as a niche interest and were keen to point out that their movie was an edgy, scary thriller rather than a horror film. However, as the generation that grew up on the horrors of the 1980s came into ascendance, fewer people regarded the horror label as pejorative.

Certain horror films have been ludicrously successful, tempting others towards the gold rush. The Blair Witch Project and Paranormal Activity have been quoted on almost every horror film business plan since they were released. And with good reason. Using data from Nash Information Services and taking into account all likely income and expenditure in the entire course of the movie’s release, it is estimated that Paranormal Activity made a producer’s net profit of around $120 million. That’s profit – not gross.

Further reading: The Horror Report and Six things every filmmaker should know about the horror genre

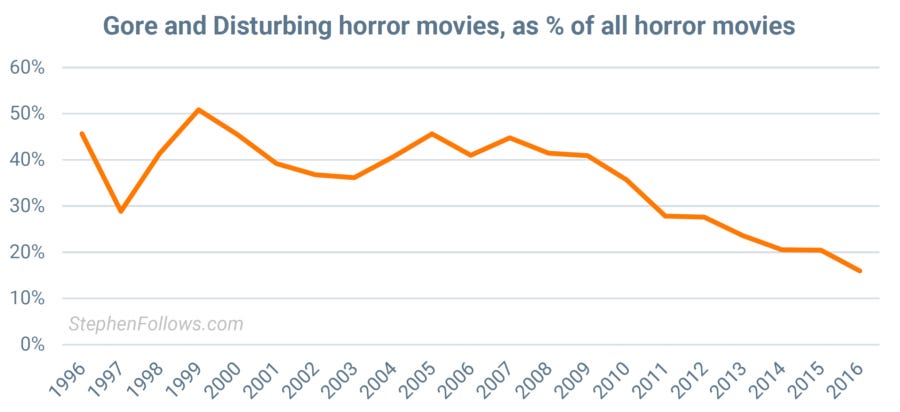

7. Horror movies are becoming less gory and disturbing

Horror movie tastes are cyclical, with particular subsets of horror going in and out of fashion. For example, horror movies get increasingly gory and disturbing over time, until the bubble bursts and lighter horror movies return. We are currently in a relative downturn for gory and disturbing movies.

Further reading: The Horror Report and Six things every filmmaker should know about the horror genre

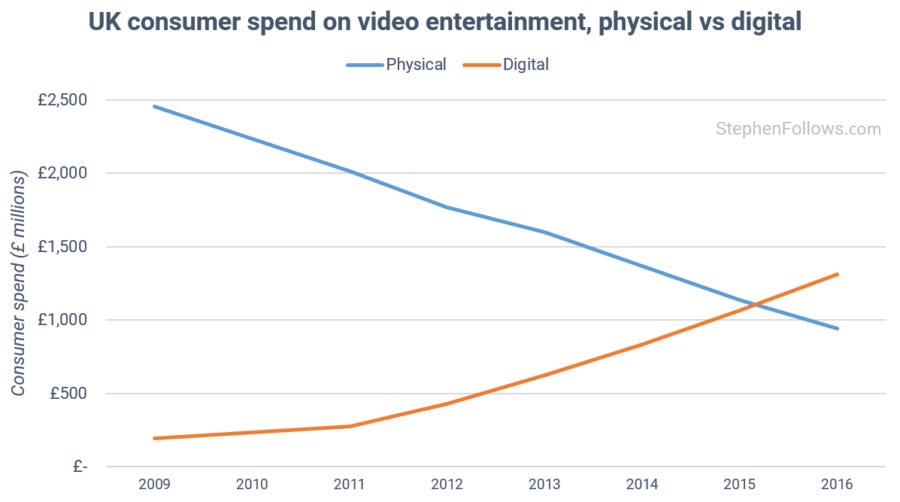

8. Digital revenues are now higher than revenue from physical formats

2016 was the first year in which overall digital video spending (i.e. retail and rental) beat spending on physical formats. The film industry was slow to move away from a reliance on physical formats, due in part to the huge income DVD had generated in the previous decade and the industry's aversion to anything new or seemingly risky.

However, consumer demand and fear of not being able to control the new digital economy has forced studios to embrace the new digital reality. In the coming years, the war for power and profits in the home entertainment space will be fought in the digital domain.

It’s actually quite hard to get exact figures because, unlike the physical marketplace, the digital marketplace is broad, diverse and often keeps numbers private. In the chart above, physical spend is as reported by The Official Charts Company and digital spend is a combination of estimates by IHS for many types of VOD (including EST, TV-VoD, web-based VoD and sVoD services).

Further reading: When and how the film business went digital and What are Video on Demand audiences watching?

9. Hollywood avoided a predicted tentpole "implosion"

It's almost a requirement that each new Hollywood movie seeks to be bigger than the last. 'Bigger' here is defined both by the scale of the production budget and the amount spent on marketing the movie worldwide. This "tentpole" theory suggests that if a mega movie can dominate cinemas and news cycles for a couple of weeks, it can overcome factors which can hold smaller movies back, such as how good it is. And it can pay off richly. Jurassic World grossed over $1.6 billion worldwide in cinemas alone, on a $150 million budget despite not being a five-star movie.

There is an inherent flaw in this 'tentpole' theory. If you need your movie to always be bigger than the last, then inflation sets in. Plus, as more studios try to get in on the game, there is increased competition for the same number of release slots. Finally, in order to pay for these bigger movies, the studios spend less on small movies, meaning that there is even more riding on the success of each tentpole release.

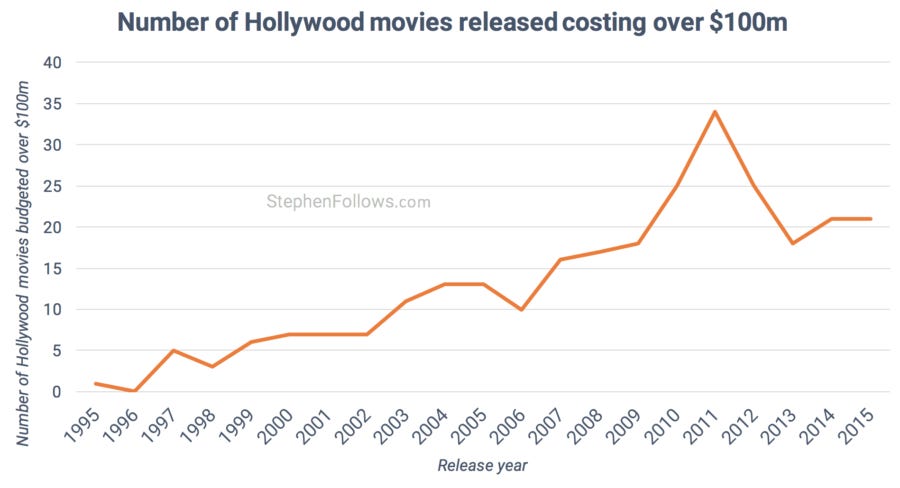

Budgets have been rising in recent decades, well above inflation. We can see this by looking at the number of movie releases where the production budget is north of $100 million. In the ten years between 1995 and 2004, there were 60 Hollywood movies released which cost over $100 million. In the following ten years (2005-14) this rose to 197.

At the start of the current decade, many industry watchers pointed out how unsustainable this cycle is and the general wisdom was that a huge crash was imminent (Steven Spielberg and George Lucas both predicted an industry ‘implosion’). However, it seems that Hollywood has reigned in spending with 2014 and 2015 having just 21 movies apiece, far below 2011’s high of 34.

Hollywood is still betting big on a small number of movies, with riskier and riskier results. Variety described 2017's summer box office results with the headline "Summer Box Office Officially Worst in Over a Decade". However, the predicted implosion predicted in the early 2010's was far less dramatic than expected. There will be more on Hollywood trends in an upcoming instalment of this four-part series.

Further reading: Do Hollywood movies make a profit? and How movies make money: $100m+ Hollywood blockbusters

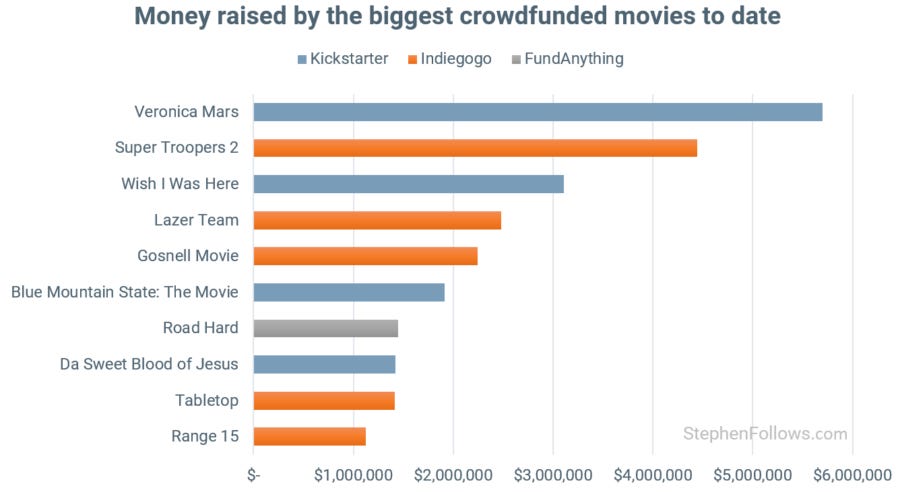

10. Crowdfunding has become a major source of independent film finance

Independent filmmakers have always had to seek film financing from a number of supporters, but in recent years it has become a lot easier, thanks to the rise of online crowdfunding. IndieGoGo was the first major platform and launched at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2008. Just over a year later, the current market leader, Kickstarter, launched and was followed by a whole slew of other sites.

Many of the first film crowdfunding projects felt homemade but as the years have gone on, the scale and level of professionalism has increased. So too has the amount these projects are seeking to raise. The biggest crowdfunded movie so far is the Veronica Mars movie, which raised $5.7 million.

Emerging from this is a service industry comprising of crowdfunding consultancies, dedicated marketers and reward drop-shippers. Crowdfunding campaigns can still be run by a few people from their bedroom but the biggest campaigns are big professional operations akin to movie marketing at film festivals or during the theatrical release.

Crowdfunding suits indie filmmakers for a number of reasons:

They don’t have to pay any money.

They don’t have to pay any interest or premium on the money raised.

No-one controls their film.

The filmmakers keep 100% of the film’s profits - normally assigned to investors.

The crowdfunding campaign can build a loyal following even before the film has been made.

It’s open to everyone - the only unavoidable cost is the commission charged by the platform, if the campaign succeeds.

And soon Hollywood could be following suit. A recent change by the Securities and Exchange Commission in the US means that film producers will be allowed to seek investment via crowd-financing. This differs slightly from traditional crowdfunding as these investors are entitled to a cut of the profits, but the core idea of many people chipping in small amounts is the same.

Further reading: The statistics behind film crowdfunding: Part 1, How much do Kickstarter film projects aim to raise?, Film crowdfunding tips – What the data says you should do, How many filmmakers run multiple crowdfunding campaigns?, The film financing of a £660k feature film and Is Seed & Spark’s high crowdfunding success rate for real?

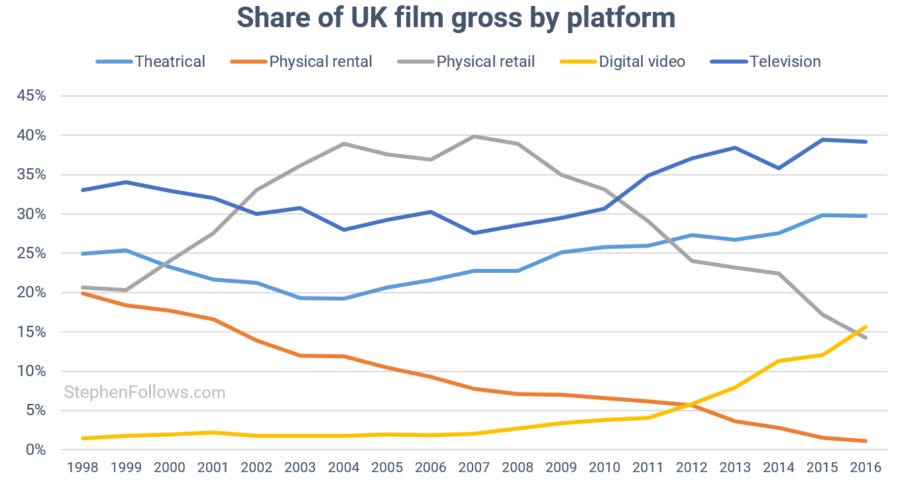

11. The biggest source of income for filmmakers is now television

In the 1990s, television deals represented the largest source of income for feature films. The DVD boom of the 2000s meant that physical video overtook it: at their height in 2004, physical sales and rentals together accounted for 51% of total film revenue in the UK. In more recent years, physical video has plummeted in value and in 2016 accounted for just 15% of UK film income.

This means that income from television licensing has regained its top spot, and now accounts for almost 40% of film revenues - a higher share than at any point in the past 20 years.

The picture is even rosier than it first appears as these figures are gross, i.e. income before costs. The cost of releasing a film theatrically is very high as there are the digital prints to ship to cinemas and the huge marketing campaign to launch. Similarly, releasing on physical video is expensive as there are copies of the DVD or Blu-Ray to create and ship, as well as coping with returns (plus a little more advertising). The major costs involved with television deals is the legal team doing the deal and the delivery of a few master copies. So the profit margin is much higher.

The chart I chose was for the UK, but my research shows that a similar journey has also happened in the US.

Further reading: How important is television income for filmmakers? and How movies make money: $100m+ Hollywood blockbusters

12. Budgets for some genres have shrunk dramatically

Last year, I looked into a claim made by Matt Damon in an interview. He lamented the changing nature of drama features, saying "The $15 to $60 million drama, is gone. They just don’t make that movie anymore". My research showed that on the one hand, he was wrong (i.e. those kinds of films are still made in similar numbers to the past) but that his larger point was true (i.e. it's currently a harder business environment for dramas).

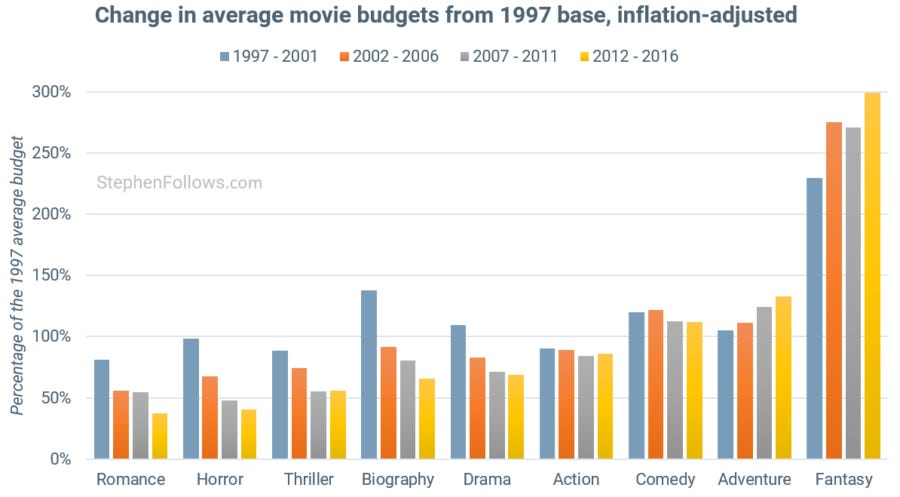

One of the interesting things to come out of that project was that it revealed how budgets have changed over the years for each major genre. I looked at the public budget for all films which reached US cinemas in the twenty years between 1997 and 2016.

Romance movies experienced the biggest decline, with their 2016 average sitting at $23.1m, compared with $52.3m in 1997. Other declining genres were Horror, Thriller and Biography. Fantasy films led the pack in budget growth, although the extreme nature of the effect shown below is in part down to an unusually low average in 1997.

Further reading: Has the mid-budget drama disappeared?

Notes

The data for today's article came from a variety of sources, including IMDb, Box Office Mojo, The Numbers, Wikipedia, comScore, BASE, Official Charts Company, Attentional, ONS, IHS, Film Distributors Association. If you want to know more about a particular chart then I suggest following the 'Further Reading' link as it will provide more context and details of the data source(s).

Epilogue

In the coming weeks, I'll share more trends I've spotted in the film industry. If you think I've missed anything important then please do contact me via my contact page or leave a comment below.