In a recent interview with the Metro newspaper, Matt Damon discussed the changing nature of Hollywood budgets and specifically the decline of mid-budget dramas. Or as the Metro headline put it “Jason Bourne star Matt Damon explains why you’re seeing less indie movies in cinemas“.

In a recent interview with the Metro newspaper, Matt Damon discussed the changing nature of Hollywood budgets and specifically the decline of mid-budget dramas. Or as the Metro headline put it “Jason Bourne star Matt Damon explains why you’re seeing less indie movies in cinemas“.

Let’s ignore the journalist’s poor grammar and focus on the point Mr Damon was making. His assertion was:

The $15 to $60 million drama, is gone. They just don’t make that movie any more.

It’s an interesting claim, so I thought I’d look into the topic.

Have all mid-budget drama movies gone?

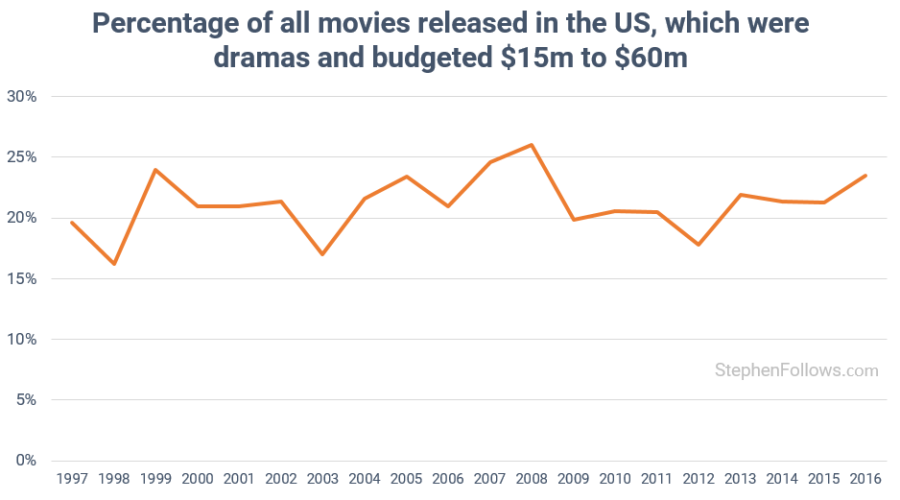

Let’s start by looking at the data. I built a dataset of all movies which grossed at least one dollar in US cinemas over the past twenty years (1997 to 2016). I then found the IMDb genre classification for each of those movies, along with the production budget, if publicly available.

If these numbers sound high, that’s because they are. Both “drama” and “budgeted $15m-$60m” are wide categories and many films get swept up in that net. As I’ve discussed before, drama is a tricky genre to classify as, strictly speaking, almost everything is drama. IMDb classifies almost 62% of movies over this period as a ‘drama’ (films can have up to three genres).

Nonetheless, even if we narrow it down to more drama-y dramas (you know – people crying and such) then we still don’t see a big shift away from such movies. In 2016 we saw the release of Gold (reportedly costing $30m), Fences ($24m), Collateral Beauty ($36m), The Young Messiah ($18.5m) and Hidden Figures ($25m).

Nonetheless, even if we narrow it down to more drama-y dramas (you know – people crying and such) then we still don’t see a big shift away from such movies. In 2016 we saw the release of Gold (reportedly costing $30m), Fences ($24m), Collateral Beauty ($36m), The Young Messiah ($18.5m) and Hidden Figures ($25m).

So on the face of it, Matt Damon was wrong. But I think the fault lies not in his fundamental point, but in how he expressed it. If we focus on the budget level, then we see a different picture emerging.

How have drama movie budgets fared over the past twenty years?

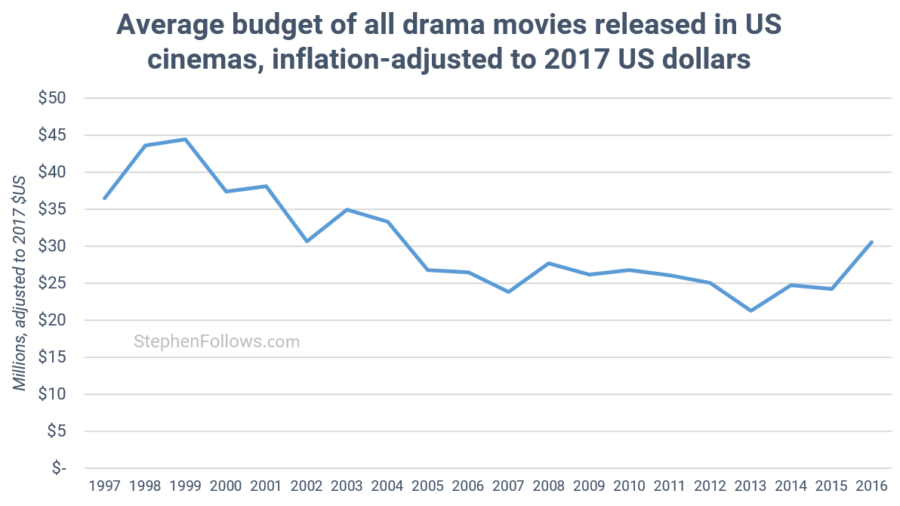

Using the same dataset, I looked at the inflation-adjusted average budgets of drama movies over the past twenty years.

The average budget for a drama in 2016 was $30.6 million, 84% of the 1997 figure of $36.5 million. However, if we look at the time series below, we can see that there have been big shifts over this twenty year period, with the 2013 figure ($21.3m) being under half that of 1999 ($44.5m).

It’s difficult to tell at this stage if the recent three-year rise will become a longer-term trend.

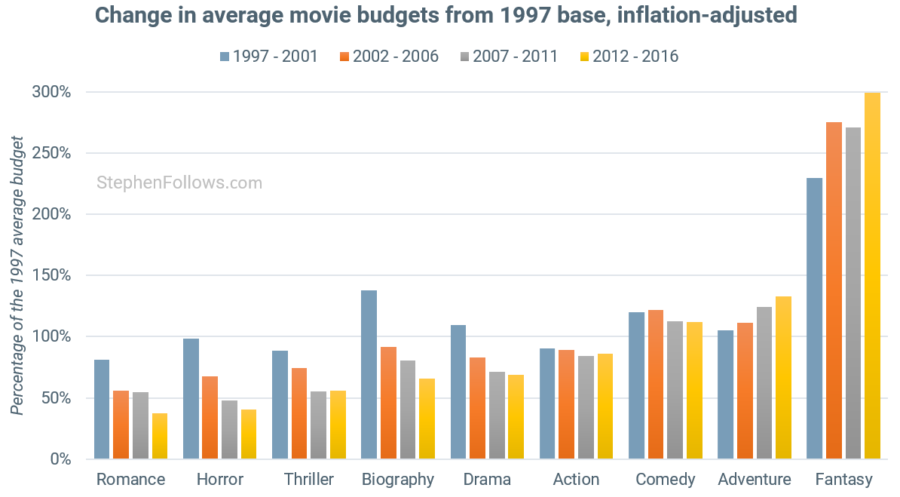

Have other genres seen budget declines?

Now that we know that drama budgets have broadly fallen, we should look at how this compares with other genres.

Of the nine major genres I studied, drama sat exactly in the middle. Romance movies experienced the biggest decline, with their 2016 average sitting at $23.1m, compared with $52.3m in 1997. Other declining genres were Horror, Thriller and Biography. Fantasy films led the pack in budget growth, although the extreme nature of the effect shown below is in part down to an unusually low average in 1997.

Dissecting Damon’s description of diminishing dramas

Overall, I’d tend to agree with Matt Damon that drama feature films are having a harder time than they used to. I don’t think it’s as stark as he points out, but he’s definitely on to something. To end this piece, I thought I’d share more of the original interview, in which he explains the three reasons why he thinks this is happening.

Overall, I’d tend to agree with Matt Damon that drama feature films are having a harder time than they used to. I don’t think it’s as stark as he points out, but he’s definitely on to something. To end this piece, I thought I’d share more of the original interview, in which he explains the three reasons why he thinks this is happening.

Firstly, he points to how hard it was to get Behind the Candelabra funded:

When we went to do Behind The Candelabra in 2012, we couldn’t get that movie made – and it had Steven Soderberg directing it and me and Michael [Douglas] – and we couldn’t get $23 million to make the movie. And that would have been a lay-up 15 years ago, it would have been five places trying to woo you.

Secondly, he rightly points out that as more of the Hollywood box office is coming from overseas, the studios need to find content which will travel to multiple countries.

You know, because the DVD market dried up. So that severely cut into the margins that studios would rather bet big on these big titles. And with this whole international audience, the more, you know, the simpler the story the more that it can kind of play, the less language matters so that the more broad appeal that it can play around the world, and that’s why you’re seeing the movies change.

Finally, he comments on the effect of SVOD content. As he puts it:

It’s a bummer for me because my bread and butter was those movies, those dramas, but there are lots migrating to TV. Television is really experiencing this renaissance and they’ve got these incredible writers who have so much more power on television than they did in the film world and they’re writing incredible stories.

Notes

The original list of movies was built using The Numbers and IMDb, and I then used IMDb’s genre classification. I found budget figures from a variety of public sources including Wikipedia, The Numbers, Box Office Mojo, IMDb and interviews with the filmmakers. Of the original 7,617 movies which were released in US cinemas, I was able to find budget figures for 4,173 (55%).

Epilogue

In an epilogue a few weeks ago, I mentioned that a Liam Neeson production was denied permission to shoot in a Canadian national park and that the park ranger in question should perhaps go into hiding, just in case Mr Neeson is anything like his on-screen persona. It seemed funny at the time but now that I’m including in an article the phrase “Matt Damon was wrong”, I find myself wondering if the park ranger has a spare bunk in her secret underground hideout.

In an epilogue a few weeks ago, I mentioned that a Liam Neeson production was denied permission to shoot in a Canadian national park and that the park ranger in question should perhaps go into hiding, just in case Mr Neeson is anything like his on-screen persona. It seemed funny at the time but now that I’m including in an article the phrase “Matt Damon was wrong”, I find myself wondering if the park ranger has a spare bunk in her secret underground hideout.

At least it’s a bit more of a lottery with Matt Damon than Liam Neeson. I could be hunted down and taught valuable lessons about life and maths. Or just have my wallet picked by a ragtag team of tricksters. Or maybe a group of unconvincing dragons and bad Chinese actors will bore me to death? Only time will tell.

To be honest, I’m equally worried about him setting off to find me, getting stranded and causing many people to lose their lives trying to rescue him (à la The Martian, Interstellar, Saving Private Ryan).

Comments

As someone shooting films in the range discussed here for the last 35 years, I can offer anecdotal evidence of the budget declines that you have identified. From around 2000, every production seemed to get worse and worse in terms of every conversation being prefaced by “we have no money..”. Whilst all of us “below the line” (the people who actually make the film) have had our wages reduced, it would be an interesting study to see if those “above the line” (mostly the Stars, Producer (s) and Director) have also suffered a reduction in salary.. The perception (of course!) is that the crew gets shafted whilst everyone else is fine.. Not sure how you study that!

Thanks for another interesting piece.

Well, this is confusing. It has been the received wisdom (at least for readers of Variety) that the collapse of the DVD market has made it a lot harder for mid-budget dramas and rom-coms. Actors and directors complain constantly about how mid-budget films are tougher to finance than the sunny uplands of the 1990s.

How inconvenient of the numbers not to bear this out in a satisfying graph.

Hi Jack. Yup, this isn’t what I expected to find when I approached the topic. However, this is why data research is so important.

As shown above, budgets are falling so there is pressure on this sub-sector. Also, most possible projects don’t happen and so when they fail, people look for a narrative they can pin it on. It seems just as likely to me that the Behind the Candelabra struggles were down to homophobia. Or a bad proposed recoupment schedule (due to big stars’ back end deals). Or a small target audience (it’s not a film which would attract the largest demographic of cinema goers). Or for any number of other reasons.

One thing that will alway be difficult to nail down is to what extent people are only talking about highly subjective experiences and when they are reflecting wider trends. When we were conducting our research into directors last year, one thing that proved tricky was disentangling the ‘Personal’ from the ‘Industry-wide’. Many directors would say “I was held back because of [x]”, ” I had a harder time that I should have because of [x]”, “I’m being left out because of [x]”, but when when we looked at the people they said they were passed over for (i.e. the [x]), they would say the same things!

Unhappiness with the industry was not greater for one gender or another, but they had each editorialised in their heads why they were having a hard time. Some female directors saw it as sexism while some men saw it as positive discrimination. And it’s certain that some of these people were spot on – but which were the trend-spotters and which were just the bog-standard British complaints?

In the case of mid-budget dramas, we all love hearing a story of how quality films just can’t get made anymore. It speaks to our image of an increasingly dumber industry. And maybe that is partially true. But it’s nearly as bad as you’d think, if you only listened to anecdotes told at film festivals and in the trade press.

Oh, and the number of films made does not reflect how hard it was to get financed. I.e. it may be that it now takes much longer to get a mid-budget drama off the ground than it used to – I can’t track that.

Damon’s lament is an extremely common one in the industry. I first heard it from Taylor Hackford at the AFCI Cineposium conference in 2007. But generally it seems it’s directed at the major studios.

At this point we are looking at a landscape where theatrical still has not returned aside from some big-budget outliers, and that everything has to make its life through streaming. The rates paid by the streaming companies, from what I am told, are horrendous (one distributor told me Prime Video was paying $.01 *per hour* of viewing). Is there any way of seeing the amounts the major streaming companies are paying to license properties? That is going to have a gigantic impact on whether indie films have any chance to make money at all.