Three years ago, I looked at Hollywood’s switch from shooting on film to using digital acquisition methods.

Three years ago, I looked at Hollywood’s switch from shooting on film to using digital acquisition methods.

Since then, I have received a number of questions about the topic. Some are requests to update the piece with more recent data while others ask for more detail on how the use of digital formats differs between genres.

As requested, this article will bring the data up-to-date, add twice as many films (looking at the top 200 movies each year, where previously I looked at the top 100) and go into more detail over the differences between genres.

Tracking the switch from film to digital

I researched the cameras used on all live-action fiction feature films within the top 200 grossing charts of each year. Please see more details of my methodology and criteria at the end of the article.

As the chart below shows, digital formats had overtaken film by 2013. Five years later, there is no competition. Of movies released in 2018, 91% used a digital format and just 14% used film.

N.B. Movies can use more than one camera, and therefore more than one format type, hence why the chart above sometimes adds up to more than 100%.

Taking stock of stock taking

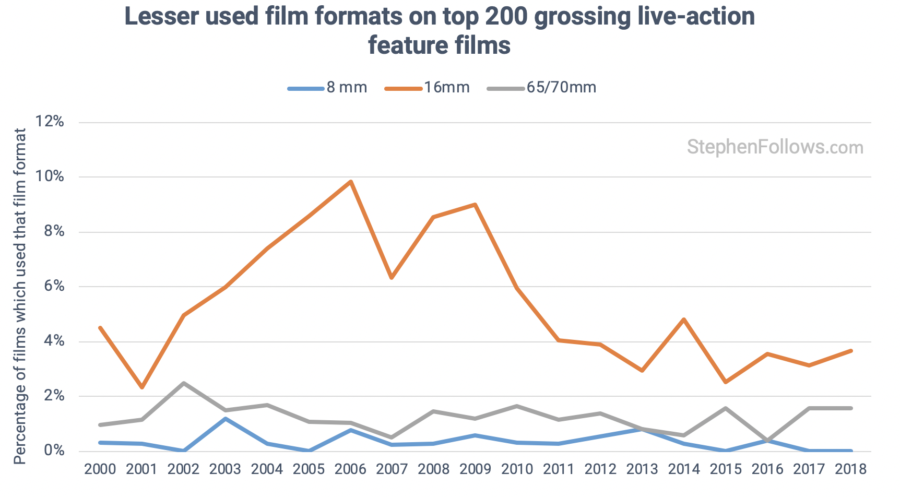

Of those which shot on film, the vast majority used 35mm stock. However, it is not the only size of film stock used on the films in my dataset:

- 8mm gives a hugely grainy look and when used is usually only for short moments, although some 8mm features do exist.

- 16mm has historically been used to shoot films with low budgets, such as Clerks (Kevin Smith’s first feature), Following (Christopher Nolan’s debut) and El Mariachi (Robert Rodriguez’s first). The cost-saving nature of 16mm has largely been supplanted by digital formats and we’re seeing more features shot on consumer cameras, such as Steven Soderbergh’s Unsane which was shot on an iPhone. The artistic use of 16mm remains and it can be used to achieve a grainy, stylised look, such as for Black Swan.

- 65mm / 70mm is primarily used for films intended for IMAX screens although can also be used for artistic reasons, such as Dunkirk and The Master.

16mm losing its place as the de facto ‘cheapest professional film option’ has meant that films shot on that format have declined as the use of digital has risen.

Digital dynasties

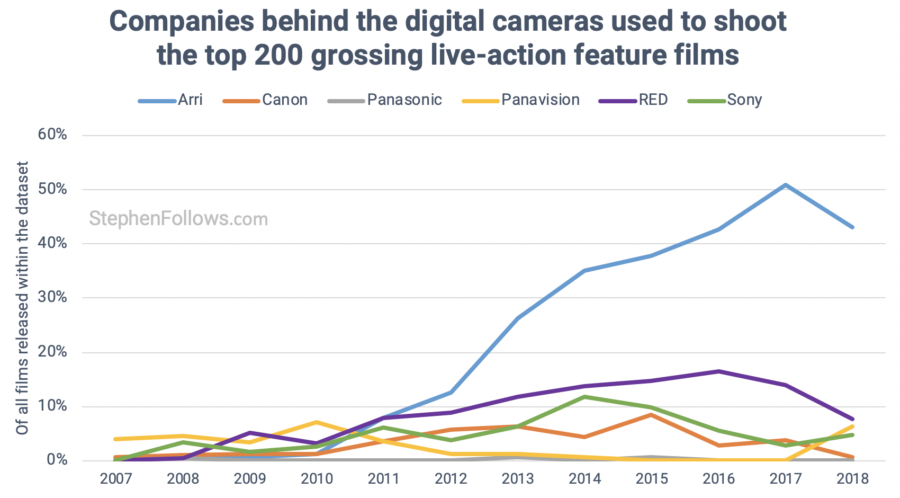

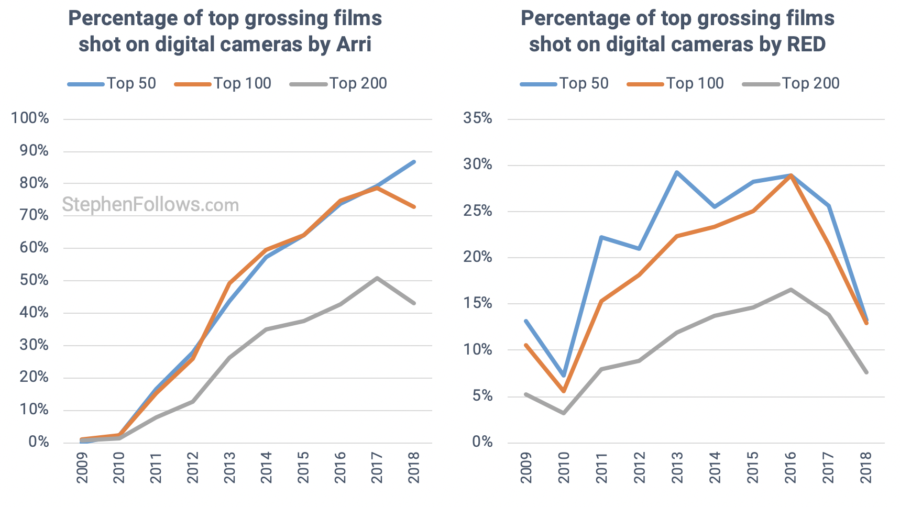

Arri leads the field in digital cameras, at least in the number of top-grossing films which use their tech. This includes their Alexa family of cameras (including the Mini, Studio, XT, SXT, Plus and 65) as well as their older models such as the Arriflex D-20 and D-21.

Arri’s dominance is at its height among the biggest movies, with around 80% of top 100 grossing movies using an Arri digital camera in 2018. The charts below show their market position (and that of their nearest rival, RED) in top 50, 100 and 200 grossing movies.

Genre differences

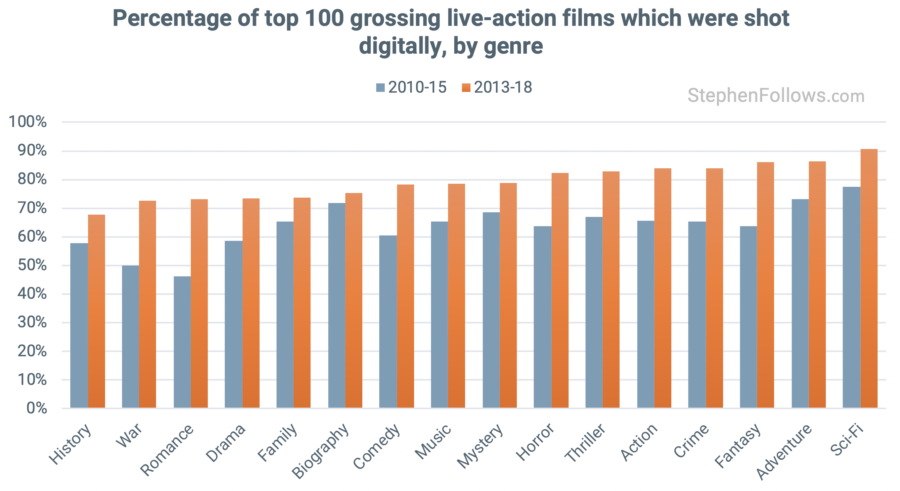

In my original article, I looked at what percentage of films of each genre were shot digitally over a six-year period (2010-15). It showed that 77% of sci-fi films had switched to digital but that only 41% of romantic films and 33% of war films had followed suit. At the time I spoke to a Director of Photography who said: “History films shoot film more because it’s softer and people associate it with a period look now and Romance because film still makes actors look more attractive than digital”.

By adding the last three years to the dataset, we can see how things have changed.

Sci-fi movies are still the most likely to be shot digitally (now at 91%) and war and romance films are still among the least (both at 73%). Although the order has remained very similar, we can see that all genres have increased their reliance on digital formats.

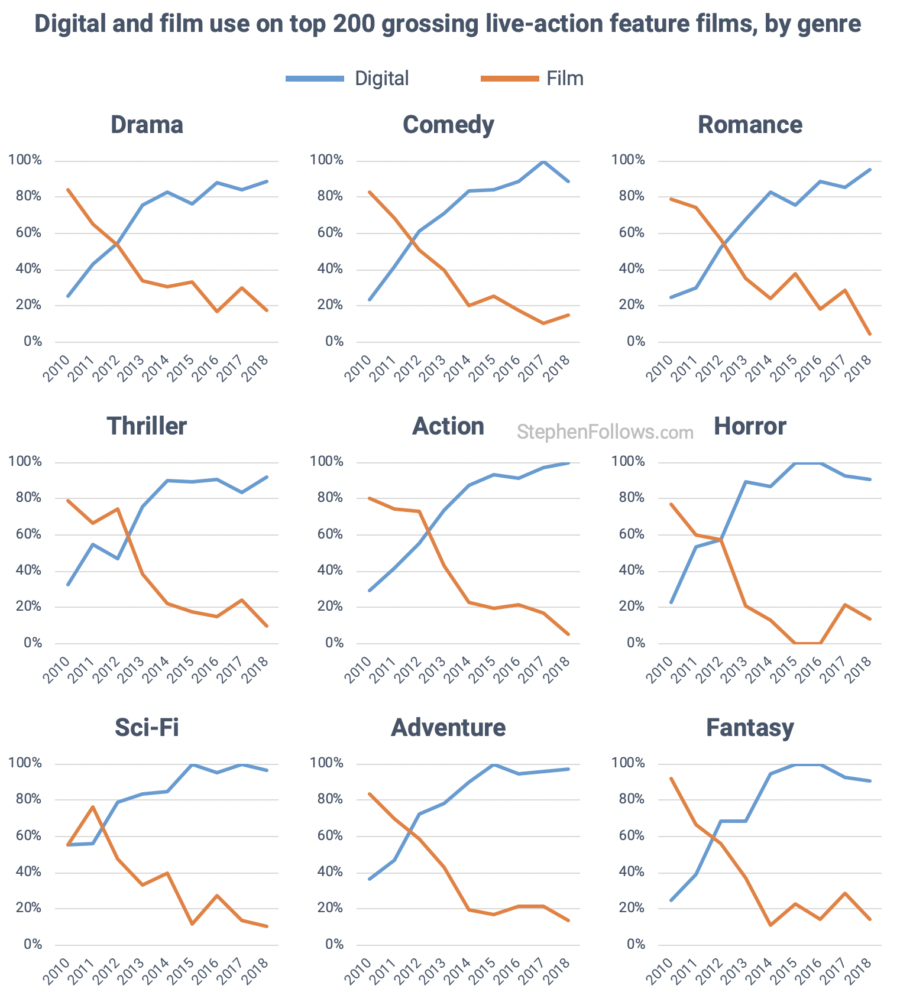

If we drill in a little deeper, we can see roughly when digital overtook film. Action was one of the last major genres to prioritise digital over film, while sci-fi was the first.

Notes

Today’s piece has been designed to give neat answers to complex questions. Therefore, I have done some generalising and grouping to provide this overview. For the majority of readers, this has made the results more readable and understandable. However, cinematographers and those who want more detail may be left somewhat lacking.

To appease my fellow pedants (and to beg for forgiveness), here are some caveats on the classification system used:

- I grouped the film types by stock size, which means that “16 mm” includes Super 16mm and “35 mm” includes VistaVision (where 35mm stock runs horizontally thereby giving a much larger image).

- The ‘digital’ moniker refers to acquisition format, not sensor type. Many later tape formats were cameras with digital workings but which outputted to physical cassettes, such as HDCAM and HDV. This sometimes happened in the middle of a camera brand’s lifecycle, such as Sony’s CineAlta range which initially recorded to HDCAM tapes and now is fully digital. I have tried to take account of when things like this changed by indicating if a film shot on the CineAlta should be classed as Digital or Tape.

- Some cameras are collaborations between companies or feature tech from more than one source. For example, Panavision’s Millennium DXL2 features the RED Monster sensor. In this research, I listed this under Panavision.

- Erroneous data. I have done my best to discover the formats used for each film and for the most part I am confident they are right. However, there can always be the odd error in online materials and sometimes even on the actual end credits. For example, the latest Transformers prequel, Bumblebee, was shot spherically on the Arri Alexa but lists “Filmed in Panavision” at the end of the film.

And here are notes on the choice of films I focused on:

- This is a study of live-action fiction feature films. Therefore, it does not include short films, documentaries, concert/stand-up films or films which have no live action elements (i.e. entirely animation or CGI films). This was done partly to focus the research but also because those types of films have a much poorer record of the cameras used (i.e. it’s below 30% for theatrically released feature documentaries).

- I used IMDb’s genre classifications, for which each film had an average of 2.5 genres.

- References to the ‘Top’ films all relate to the Domestic box office gross for each year. The ‘Top 100’ may have fewer than 100 films as it will be the 100 highest grossing films, minus the movies which don’t fit into my ‘fictional live-action’ definition above.

- The dates refer to the movie’s release date, not when they were shot. Thanks to my previous research, I can say that the average Hollywood movie takes 106 days to shoot and reaches US cinemas just under a year later. Therefore, the choice for camera formats was made at least a year and a half before the dates shown on the charts. As it varies for each movie, I thought it better to focus on the standardised date of the first US public screening.

- Percentages are for all films for which I could determine the camera format(s) used. Overall, I discovered the format for 98% of the top 50 grossing movies, 96% of the top 100 and 91% of the top 200.

- The charts showing Film, Digital and Tape use may add up to more than 100% as films can use a variety of formats, thereby increasing the count for more than one format.

- My original article only looked at the top 100 grossing films, hence why some of the charts look slightly different from today’s, covering the top 200. In addition, it can take time for information about the cameras used to be released, meaning that my data for the years 2014 and 2015 are more accurate than in my previous research project.

My raw data came from IMDb, Wikipedia, ShotOnWhat (where possible as their site is unstable – donate to help keep them alive), camera company sites and other public sources.

Epilogue

This is one of those topics where no matter how much research you do, you never feel satisfied. There is so much more detail to go into but it is impractical to do so, either because of time constraints or data availability. For example, I wasn’t able to take into account the amount of footage each camera was used to capture. A film like The Ring used both 35mm and VHS video, but far from equally.

It’s also likely to spark impassioned discussions from advocates of film, of digital formats and those who propose being format agnostic. When debates are this active, I’d like to be able to provide fuller, richer results.

If there are any other topics I have covered a while ago which you feel are in need of a fresh look, please do drop me a line.

Comments

Hi Stephen,

Interesting analysis! But I’m sure you realize that the “tape” formats in use with these cameras, such as HDCam, are digital. By “fully digital” you presumably mean digital memory cards or hard drive recording, but digital tape (or optical disc) are still fully digital. Analog tape in production petered out over a decade ago.

Workflow, of course, can be quite different with tape, as would the choice (or lack thereof) of acquisition codecs and other parameters that were not possible with dedicated tape formats.

Hi Eric. Thanks! Yup, I noted in the ‘Notes’ section at the bottom this choice in the research and how it still leaves some issues unaddressed. With more complete data I would love to be able to drill down deeper.

The ‘Which camera?’ question can be somewhat blurred by the use of multiple cameras (e.g. Jason Bourne shot on Arri and Blackmagic Design). One tends to only report the top-end cameras such as Arri Alexa and leave the budget cameras unmentioned!

Panasonic, Panavision and BMD are growing their film camera sectors rapidly, which probably accounts for the downturn for Red and for Arri in the lower budget movies. As nearly all cameras are rented, the rental fee for a big budget movie is pretty irrelevant.

I am somewhat puzzled by the use of film, when the footage is transferred immediately to digital – much of that ‘filmic’ look was created by films being a copy of a copy of a copy, i.e. third generation of an analogue transfer.

The majority of Jason Bourne was actually shot on 3-perf 35mm, though they used s16mm and digital for certain sequences when called for. The BM Micros they used were on the second unit, where the camera’s size allowed them to get shots they couldn’t otherwise. First unit digital stuff was on the Alexa.

As for why someone would use film even if it gets scanned for editing: Scanned film still looks different than digital. You’re right that it doesn’t look like movies that were edited physically, but it does look different than digital capture. Another reason has to do with the workflow — i.e. film demanding more care and attention on set.

“Bumbelbee” … couldn’t it have been shot on Panavision owned and Panavised Arri Alexas?

Quite possibly. This is too detailed for me to be able to say from my knowledge/experience and so I’ve gone with what I’ve seen reported by smarter people than I. If someone knows for sure, please let me know and I’ll update the article accordingly.

This may be changing now, but in the past I thought the “Filmed in Panavision” tag was reserved for projects that used Panavision anamorphic glass while projects that rented spherical glass from Panavision would carry the slightly different tag “Filmed with Panavision Cameras and Lenses”.

I always wanted to know the Hollywood trend as regards shooting on film or digital cameras. And what camera are preferred. So now I know digital is preferred over film. And Arri and Red cameras are the most popular. My debut feature will take this into account.

Thanks for the very detailed article! Great work!

What an amazing insight! Thank you…

Fascinating! I love your work!

Is Black Magic a camera worth considering for a low-budget film that wants to ‘look good’?

Great article and comments. I asked my family if they knew anything about digital vs celluloid film and they had no idea what I was talking about. My question is concerning the use of Final Cut Pro in the professional sphere vs. other software entities.

I have used Final Cut Pro since it was invented. I have repaired 3D sequences from others on it. It is a software with many advantages, not the least of which being its relatively open framework allowing stunning third party offerings in the form of plugins and direct use of Acrobat Plugins. I’ve worked with RED files effortlessly.

Nikon’s purchase of RED bodes well for Final Cut users. Among these users are award wining filmmakers.