Last week, the BBC broadcast ‘The Great Gangster Film Fraud‘, a feature-length documentary which told the true story of an attempted scam by two “filmmakers”. They used a combination of tax frauds in an attempt to claim £2.5 million from Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC). They said they had made a £20 million film and so were entitled to money back via the Film Tax Relief (FTR) scheme. When they were accused of fraud, they hastily rushed out a film for £84,000 in the hope this would placate HMRC (called ‘A Landscape of Lies‘, seemingly without a hint of irony). It didn’t work and in 2013 the first ever prosecution of a FTR fraud case took place in which Aoife Madden and Bashar Al-Issa were jailed for four years and eight months and six and a half years respectively.

Last week, the BBC broadcast ‘The Great Gangster Film Fraud‘, a feature-length documentary which told the true story of an attempted scam by two “filmmakers”. They used a combination of tax frauds in an attempt to claim £2.5 million from Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC). They said they had made a £20 million film and so were entitled to money back via the Film Tax Relief (FTR) scheme. When they were accused of fraud, they hastily rushed out a film for £84,000 in the hope this would placate HMRC (called ‘A Landscape of Lies‘, seemingly without a hint of irony). It didn’t work and in 2013 the first ever prosecution of a FTR fraud case took place in which Aoife Madden and Bashar Al-Issa were jailed for four years and eight months and six and a half years respectively.

The documentary’s broadcast led to a number of people emailing me to ask about the film tax scheme. So, below I have provided more detail and data on the current and past UK film tax breaks.

How does the Film Tax Relief (FTR) work?

![]() The FTR came into force on 1st January 2007 and all British films are eligible. In the documentary, they incorrectly claimed that the FTR is 25% of the money spent on the film. The truth is that it’s slightly less, and a more complicated calculation. In practice, it normally accounts for just under a fifth of the money a film spends in the UK. For example, indie film Papadopoulos & Sons received 19.1% of their £825,000 budget back via the FTR.

The FTR came into force on 1st January 2007 and all British films are eligible. In the documentary, they incorrectly claimed that the FTR is 25% of the money spent on the film. The truth is that it’s slightly less, and a more complicated calculation. In practice, it normally accounts for just under a fifth of the money a film spends in the UK. For example, indie film Papadopoulos & Sons received 19.1% of their £825,000 budget back via the FTR.

The full calculation is that a film can claim 25% of either…

- 100% of the film’s UK Core Expenditure; or

- 80% of total Core Expenditure; whichever is lower.

“Core Expenditure” is defined as expenditure incurred on production activities (pre-production, principal photography/animation shooting/designing/producing and post production) which take place within the UK, irrespective of the nationality of the persons carrying out the activity. A further benefit is given to companies which have a Corporation Tax liability in the same year (and so the FTR can be offset against tax they owe rather than being paid out as a cash rebate). Their relief is set to 28%, in place of 25%. Films budgeted over £20 million used to receive a lower FTR rate of 20% but in March 2015 this was increased to match that of films budgeted under £20 million (25%).

In order to qualify for the relief a film must:

- Be intended for theatrical release (it doesn’t actually have to get a release, the filmmakers just have to have a reasonable expectation that it could be sold to the paying public in commercial cinemas),

- Have spent a minimum of 10% of its qualifying production expenditure within the UK,

- Be officially “British”, meaning that it must either pass the Cultural Test for Film or be certified as an official co-production

- Be made by a production company within the UK Corporation Tax net.

The Cultural Test for Film is managed by the BFI and awards points for a variety of the film’s attributes. Producers need to score at least 18 points (out of a possible 35) in order to pass the test. Over the years, the Cultural Test has been revised a few times, most notably to expand the eligible nationalities. Initial versions of the Cultural Test required that characters, cast and crew be British in order to trigger the relevant points whereas the current wording has changed from ‘British’ to read ’British or EEA citizens or residents’.

Therefore, a film could pass the British Cultural Test for Films if it were:

- Set in Spain…

- … with German characters…

- … based on a Polish short story…

- … in which everyone speaks Hungarian.

If you want a brief, fun dalliance into the world of “British” films, then check out this quiz I have put together, which asks you to guess which of ten films are officially British stephenfollows.com/quiz-guess-which-movies-are-officially-british.

How much is it worth?

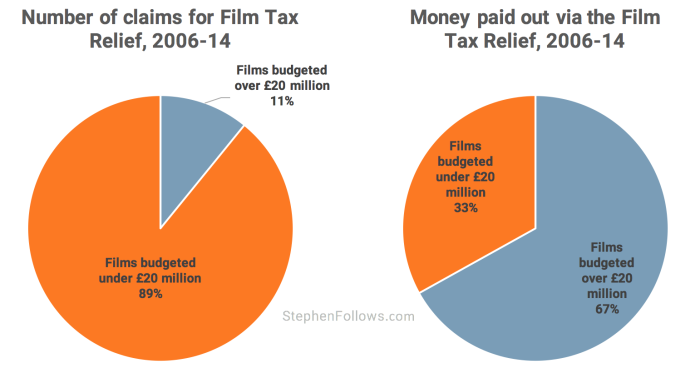

In the seven years leading up to 31 March 2014, 1,240 films received money via the FTR. Interestingly, that is just 74% of the 1,680 films which were eligible to claim money over that period. The data doesn’t reveal the reasons why the 440 eligible films didn’t claim the money they were entitled to.

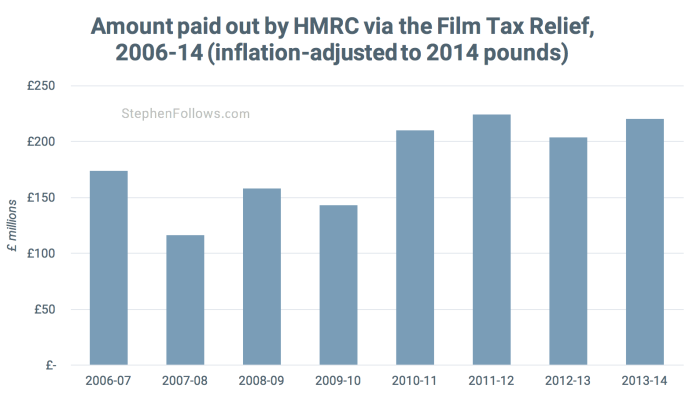

The total amount paid out via the Film Tax Relief 2006-14 was worth £1.45 billion (the raw figure is £1.36 bn but I’ve inflation adjusted the figures to 2014 pounds).

Who’s receiving the money?

In order to receive tax relief, a film needs to apply via a single UK limited company (known in taxland as the Film Production Company, or FPC), and the money is paid out as part of their annual Corporation Tax returns. This method was designed in order to benefit the film’s producers, unlike previous tax schemes which were written in such as a way that the benefit tended to go straight to the investors. However, in practice the money received via tax relief is typically used in one of a few ways…

In order to receive tax relief, a film needs to apply via a single UK limited company (known in taxland as the Film Production Company, or FPC), and the money is paid out as part of their annual Corporation Tax returns. This method was designed in order to benefit the film’s producers, unlike previous tax schemes which were written in such as a way that the benefit tended to go straight to the investors. However, in practice the money received via tax relief is typically used in one of a few ways…

- To complete the film’s budget. In this case, the film’s producers would borrow money on a short-term basis and then repay it when the FTR is paid, or arrange with suppliers for their invoices to be paid late (often post-production houses are open to such deals as they are the last people working on the film before the company can apply for tax relief).

- As first income for investors. Almost all income streams are uncertain, so many producers see the FTR as a way of being able to guarantee to investors that the film will recoup around a fifth of its budget within a few months of completion.

Films of all budget ranges are eligible, although as the FTR is a proportion of money spent, the films which spend the most receive the most back. Only 11% of claims were made by films budgeted over £20 million, although they accounted for 67% of the money paid out. This means that films over £20 million received £850 million from the UK taxman (not adjusted for inflation, so the true figure will be slightly higher).

509 films made just one claim, whereas 690 films made claims in multiple years, because their production spent money across tax years.

In 2011, HMRC said that 32% of claims were paid within a month of submission, 78% were paid within two months and 96% were paid within six months. They have stopped providing such detailed data on payment times, although in 2014 they did say that 95% of claims were paid within six months.

How much did ‘Film X’ receive?

The BFI releases the names of all films which have received their British Film certification, going back to 2007. The only details given are the film’s name and the date the certificate was issued – no financial data.

The BFI releases the names of all films which have received their British Film certification, going back to 2007. The only details given are the film’s name and the date the certificate was issued – no financial data.

However, due to the way most feature films are structured, if you’re willing to turn detective then it’s usually possible to find out how much a film earned via the Film Tax Relief. That’s because the vast majority of films are made within a specifically created limited company (known as a Special Purpose Vehicle, or SPV). When a producer submits an application for tax relief they need to do so via a UK limited company, and the rebate is then paid into that SPV. All UK limited companies are required to file a summary of their accounts with Companies House and so, if you can find the correct limited company linked to the film you’re researching, then you can often see how much tax was paid in.

Below are a few examples I found while investigating the topic. The ‘Tax’ figure is the total amount the limited company claimed back in tax since the SPV was set up, and it’s reasonable to assume that all (or almost all) of this will be the film tax relief. The ‘Cost of Sales’ figure is the total amount of money spent by the company, representing the share of the production’s budget which was spent in the UK.

| Film | Limited Company | Tax Received | Cost of sales |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avengers: Age of Ultron | Assembled Productions II UK Limited | £ 31,892,077 | £ 208,027,439 |

| Thor: The Dark World | Asgard Productions II UK Limited | £ 25,598,273 | £ 164,693,757 |

| Muppets Most Wanted | More Muppets Productions Limited | £ 6,703,273 | £ 45,089,149 |

| Jungle Book | Raksha Productions Limited | £ 5,535,527 | £ 53,279,166 |

| Ant-Man | Pym Particles Productions UK Limited | £ 509,114 | £ 23,683,575 |

| Prince of Persia | Dagger Of Time Productions Limited | £ 15,118,879 | £ 128,607,761 |

| Maleficent | Briar Rose Productions Limited | £ 23,535,108 | £ 167,277,249 |

It’s worth noting that this an imperfect method for finding the exact figures, as from the outside we can’t know if they had other reasons to claim back tax or if money was spent on the film outside of these SPVs.

Some of the films may not have been finished and future filings may reveal a larger budget and greater tax relief claims. For example, Jungle Book began shooting on 12 August 2014 and so far they have only had to file one year’s worth of accounts, up to 31 January 2015. It seems unlikely that this tentpole Disney film with an A-list cast will only cost the £53 million ($75 million) declared so far.

Finally, some films will only have set up a UK limited company to cover the UK portion of the film’s work. For example, the UK limited company linked to Ant Man budget spent £23.6 million ($33.6 million), which is just a quarter of the $130 million (£91.6 million) budget listed on Box Office Mojo.

What existed prior to the current Film Tax Relief scheme?

Government film incentives are almost as old as the UK film industry itself.

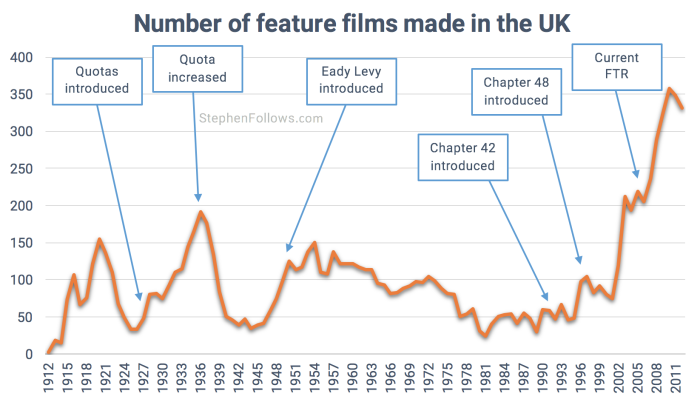

1927 & 1938 – The Cinematograph Films Act required British cinemas to show a certain percentage of British films. Initially, the cinema quota was set at 7.5% and then raised to 12.5% in 1936. To be eligible, films had to be made by a British company, any studio scenes had to be filmed in the British Empire/Commonwealth, the screenplay (or source material) had to be British and at least 75% of the salaries had to be paid to British Subjects (excluding the costs of two people, to allow for international stars).

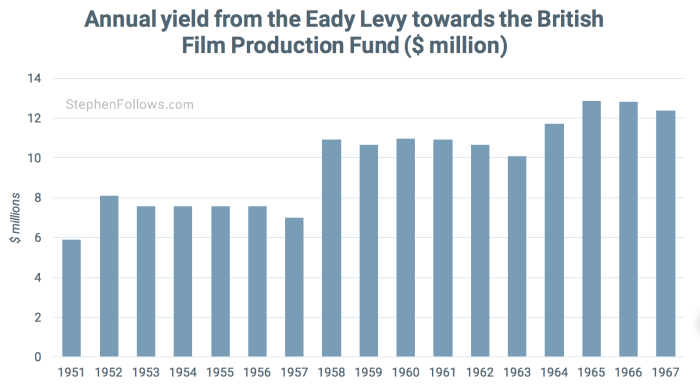

1950 – The Eady Levy was a tax on UK cinema tickets which funded projects aimed at helping the UK film industry, including the establishment of the National Film and Television School (NFTS). It came into effect in 1950, although it wasn’t until 1957 that the law was officially passed. To qualify as a British film, at least 85% of the film had to be shot in the UK (or Commonwealth), and only three non-British individual salaries could be excluded from the costs of the film. Between 1951 and 1967, the Eady Levy contributed $165 million (not inflation adjusted) to the British Film Production Fund.

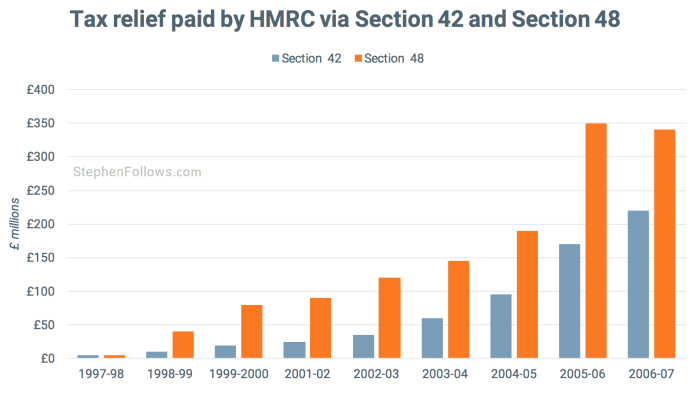

1992 & 1997 –Chapter 42 of the Finance (No 2) Act 1992 provided investors with tax savings for films of any size over at least a three-year period, and Chapter 48 of the Finance (No 2) Act 1997 allowed for immediate tax savings but only applied to films budgeted under £15 million. Via complicated partnerships, including “Sale and Leaseback”, investors could gain significant tax benefits for investing in feature films. However, despite numerous anti-avoidance provisions being added, the scheme was eventually closed (overnight, without warning) after the government concluded that the system was being abused. Between 1997-98 and 2005-06, Chapters 42 and 48 relief paid out a combined total of £1.9 billion (not inflation adjusted).

2007 – The current UK Tax Relief (FTR) scheme was established in 2007 and subsequent revisions have seen the criteria for eligibility widened and an increase in the level of relief available to big budget films (to bring them in line with the smaller productions).

Notes

If you want to read more about the history of UK film tax incentives then I would highly recommend reading David Puttnam’s excellent book ‘The Undeclared War‘.

If you want to read more about the history of UK film tax incentives then I would highly recommend reading David Puttnam’s excellent book ‘The Undeclared War‘.

The data from today’s research came from UK government press releases, Parliamentary reports, the BFI, HMRC, Screen International and a rather good paper by Jonathan Stubbs called ‘The Eady Levy: A Runaway Bribe? Hollywood Production and British Subsidy in the Early 1960s‘.

Sometimes, the data provided by the BFI and HMRC differed considerably. For example, the 2012 BFI Statistical Yearbook gives the total amount provided by the FTR during tax year 2009-10 as £95 million, whereas a statement by HMRC put the figure at £130 million. Whenever this happened I opted for the HMRC figures. One explanation could be the time it takes for claims to be submitted, processed and then for the data to filter down to the BFI in time for them to write and publish their Yearbook.

I used inflation figures from the Office of National Statistics to adjust the annual HMRC figures to be inflation-adjusted figures. This is a bit of a crude method as it just applies a single inflation figure for all HMRC payouts in each year, but as we only have the single year-end figure to work with (i.e. HMRC does not provide month-by-month or week-by-week figures for the amount of FTR payouts) it will have to do.

Epilogue

Soon after the FTR was launched, I realised that the law does not have a requirement for the length of the film. There are restrictions, such as the film being “intended for theatrical release,” but there’s nothing to stop some short films applying. I wrote an article for Moviescope magazine in 2009, showing how this can be done. I’m not sure if anything has changed in this regard but if you’re working on a short film which could be intended for theatrical release then you can check it out at stephenfollows.com/uk-tax-credit-for-short-films

Comments

Glad the relief is going to those who need it most!

Really great work. I’m currently writing my Economics dissertation about this film production subsidy and we had very similar findings. I am concluding that this tax relief is dangerous for the UK film industry, as it is now inflated far past it’s domestic (sustainable) potential, and with recent competition for Hollywood business from Canada, South Africa and Eastern Europe, it could lead to a huge downturn in the next decade. Maybe you could make a post about the cheapest countries to produce films/balanced with the best facilities. i.e. which countries are currently the best candidates for Hollywood production investment and which are on the rise.

Hi David.

I agree that it’s creating a situation which the domestic market cannot sustain but I disagree that this automatically makes it dangerous.

Firstly, the UK film industry has almost always had government intervention of some sort and so it’s a bit like looking at someone with a mortgage and thinking that they’re bankrupt. So long as the bank agree to the previous terms then the homeowner can reasonably expect to keep living in the house. By the same token, while the government remain committed to helping with film industry (as British government have been since the 1920’s), the domestic market is not required to shoulder the complete burden.

Secondly, even if these subsidies disappear, they have already provided a large number of people with a living. And thanks to the multiplier effect, this has also helped the UK economy. I don’t have the stats to hand but I believe that the estimates was that every pound put into film brought more than £4 back.

Finally, it acts a good way of building a training platform for domestic talent. The people who work on larger films also tend to support smaller films.

If you want to talk more about this feel free to contact me

Stephen

Thank you. Just the information I needed.