Short films have long been a vital part of the journey of new filmmakers, allowing them to learn new skills, meet like-minded collaborators and showcase their talent.

Short films have long been a vital part of the journey of new filmmakers, allowing them to learn new skills, meet like-minded collaborators and showcase their talent.

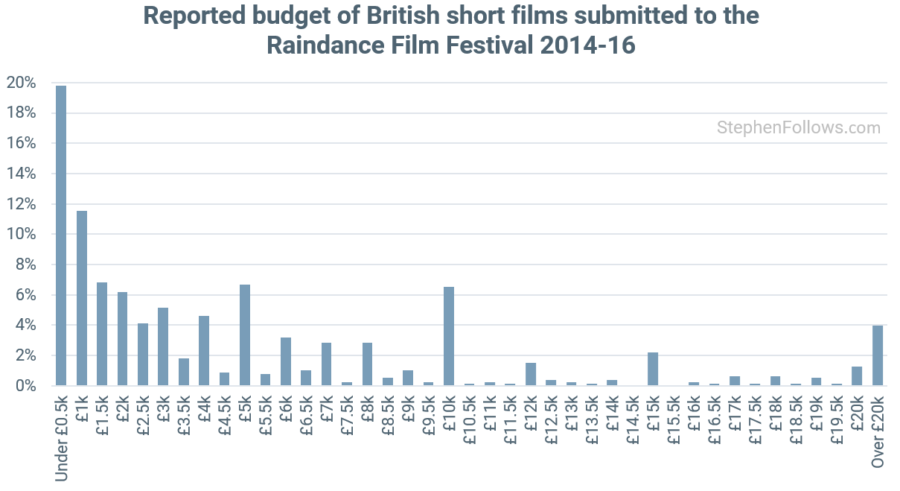

Most people’s first few shorts have a budget of almost (or exactly) nothing, with the filmmakers relying on the help of friends and family. However, as their ambition grows, so too must their budget. The cost of a short film can vary wildly, but over half of the short films submitted to the Raindance Film Festival cost more than £3,000.

Short filmmakers do all sorts of things to raise money for their short films, including crowdfunding, applying to schemes, begging family and spending their own savings. So it may come as a surprise to most British short filmmakers that they been ignoring a funding source which could give them a fifth of their budget in cash.

Let’s take a look at UK tax relief for short films…

A quick primer in the Film Tax Relief (FTR)

Ten years ago, the UK government announced their new tax relief scheme for the film industry – Film Tax Relief. FTR has been tweaked over the years but overall it has been a success for filmmakers, for the industry and for the government. It’s helped support our local films and attracted an increasing number of big Hollywood movies to the UK. The current incarnation of the FTR offers production companies of British films a cash rebate of around 20% of the money they spend in the UK.

Ten years ago, the UK government announced their new tax relief scheme for the film industry – Film Tax Relief. FTR has been tweaked over the years but overall it has been a success for filmmakers, for the industry and for the government. It’s helped support our local films and attracted an increasing number of big Hollywood movies to the UK. The current incarnation of the FTR offers production companies of British films a cash rebate of around 20% of the money they spend in the UK.

In order to claim the FTR, your film has to pass a number of conditions, including:

- Pass the BFI’s Cultural Test. This is achieved by collecting at least 18 points in their 35 point system. You can read the full details here, but suffice it to say that it would be very hard for 99.9% of British short films to fail this test.

- Be “intended for theatrical release” (more on this later in the article)

- The film is made by a UK limited company registered for Corporation Tax.

- At least 10% of your “Core Expenditure” was in the UK. The Core Expenditure is money spent on goods or services for the film during pre-production, production and post-production. Therefore you cannot claim for monies spent during development, sales or distribution.

If you pass the requirements then you can claim around 20% of your Core Expenditure back from HMRC when your company submits their next Corporation Tax return. As companies set up for movies don’t tend to owe any Corporation Tax, the FTR is typically experienced as a cash rebate.

Soon after the FTR was first announced, I wrote an article for Moviescope magazine pointing out that the legislation doesn’t have any requirements on the length of the film. This means that, under the right circumstances, short films are eligible for tax relief.

At the time of my 2008 article, it was more theory than practice. The law was still relatively new and everyone was getting their head around how some of these fringe cases would be decided. In the years since that article was published, I have been approached a number of short filmmakers wanting to know more details, and I’ve heard of the odd case of short films being successful. So I thought I’d check back in with the topic, and see how many filmmakers are taking advantage of tax relief for short films.

How many short films claim tax relief?

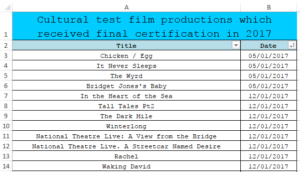

In the past, I’ve found it hard to study this topic because the BFI can’t give me a list of the short films that have passed the Cultural Test. However, they do publish a long list of every film which has passed the Cultural Test, including features, shorts and other “films” intended for theatrical release (i.e. theatre productions, concerts, museum videos, videos for rides at visitor attractions, etc).

In the past, I’ve found it hard to study this topic because the BFI can’t give me a list of the short films that have passed the Cultural Test. However, they do publish a long list of every film which has passed the Cultural Test, including features, shorts and other “films” intended for theatrical release (i.e. theatre productions, concerts, museum videos, videos for rides at visitor attractions, etc).

In that list somewhere are all the short films I wanted to research. Unfortunately, the list only contains two data points for each film – the title and the date it received its certification. This means that unless a film has a particularly unusual title, it’s hard to tell it apart from other projects of the same name.

Earlier this year, I had a brainwave and asked the BFI for a list of every feature film passing the test. They provided this and therefore I was able to deduct the features from the master list, leaving only shorts and “other” film projects. I did my best to identify the “other” film projects – some such as “National Theatre Live – Treasure Island” and “One Direction ‘Reaching for the Stars'” were clearly not short films. A very small number of projects remain elusive and so I classed them as “Unknown”.

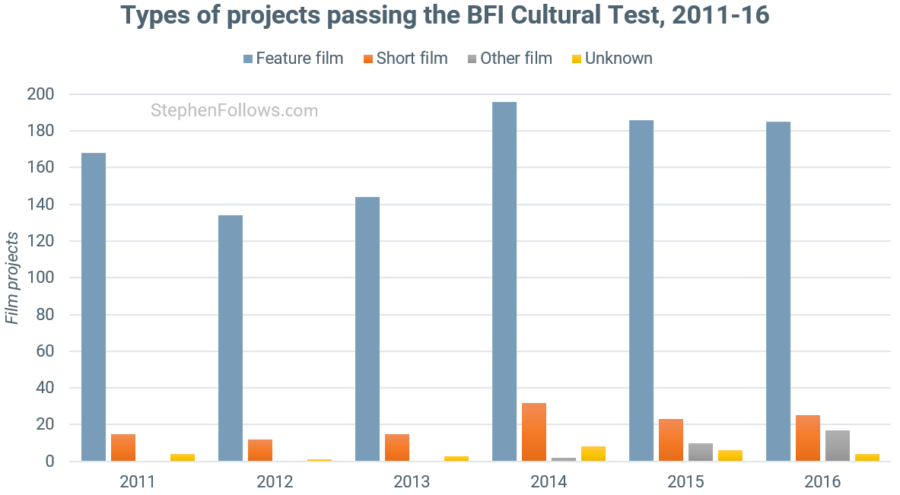

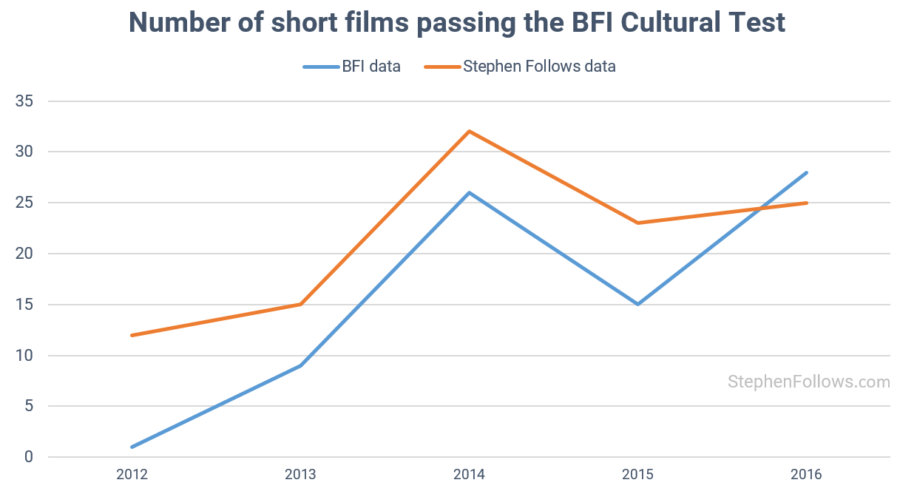

In the end, I identified 122 short films which had successfully passed the Cultural Test between 2011 and 2016.

It’s impossible to know for sure how many short films were made in the UK over that period, due to the ephemeral nature of short filmmaking. However, we can look for related data to help us gain a sense of scale for what it means that an average of 20 short films a year received tax credit payouts.

IMDb lists 21,923 UK short films as produced between 2011-16, an average of 3,654 a year. That said, some of those are promotional online videos and other film content which many short filmmakers may not class as a proper “Shorts”. A better metric may be the number of British short films submitted to the Raindance Film Festival. Between 2014 and 2016, 2,118 UK shorts were entered, an average of 706 a year.

So we can’t say exactly what percentage of British films are claiming the tax credit, but it’s certainly less than 3%, and possibly as low as 0.5%. This is in sharp contrast to the almost 100% of UK feature films that claim the tax credit.

How do filmmakers pass the ‘intended for theatrical release’ requirement?

Assuming that your short film is a typical English-language film made in the UK, then you’ll find passing all but one of the FTR tests very easy. The tricky part is proving that your film is “intended for theatrical release”. Interestingly, you don’t actually have to make it to the big screen, just prove a professional intention.

There are two ways to address this requirement, which I shall label the ‘Lawyer’s Approach’ and the ‘Producer’s Approach’.

The Lawyer’s Approach means we need to go into the detail of the law, to understand how HMRC decide on when an intention is valid. HMRC define “theatrical release” as:

The Lawyer’s Approach means we need to go into the detail of the law, to understand how HMRC decide on when an intention is valid. HMRC define “theatrical release” as:

‘Theatrical release’ means exhibition to the paying public at the commercial cinema. A film is not regarded as intended for theatrical release unless it is intended that a significant proportion of the earnings from the film should be obtained by such exhibition. The phrase significant proportion is not statutorily defined; its level will depend on the facts in each case. But HMRC will accept that 5% of total estimated income is a significant proportion the earnings of a film.

They also go on to state what kinds of documents could support someone’s ‘intention’. These include:

- a finance plan written on the basis that the film will be released theatrically;

- a normal full-length or short feature film of a type commonly shown at cinemas;

- production in a format suitable for theatrical showing at the commercial cinema;

- payment to actors and other participants on terms in line with those prevailing for cinema films (rather than, for example, television work), and;

- the relevant person can demonstrate, at the end of the relevant accounting period, the intention to seek a contract to present the film in the cinema.

They also state that it would hurt your case is “there are no commercial cinemas which show the particular type of film”.

So the Lawyer’s Approach suggests you should create finance plans, ensure you have a Digital Cinema Print (DCP), pay your cast and crew at BECTU film rates and secure distribution deals ahead of your FTR application.

Now let’s look at what I am calling the Producer’s Approach… just book screenings.

Now let’s look at what I am calling the Producer’s Approach… just book screenings.

For years, to be in the running for the Oscar short film longlist you had to pass one of two tests: either win one of a small number of top film festivals, or pay for a “commercial release” in LA cinemas. The Academy Awards rulebook even sets out the fine print for what type of paid-for release will be permitted. This includes:

The picture must have been publicly exhibited for paid admission in a commercial motion picture theater in Los Angeles County for a run of at least seven consecutive days with at least one screening a day prior to public exhibition or distribution by any nontheatrical means. The picture also must appear in the theater listings along with the appropriate dates and screening time(s). All eligible motion pictures must be publicly exhibited by means of 35mm or 70mm film, or in a 24- or 48-frame progressive scan Digital Cinema format with a minimum projector resolution of 2048 by 1080 pixels, source image format conforming to ST 428-1:2006 D-Cinema Distribution Master … The audio in a Digital Cinema Package (DCP) is typically 5.1 or 7.1 channels of discrete audio

This language is for the Oscars, not UK tax relief, but it gives an indication of what a proper paid-for release looks like.

I can’t give you any accounting or legal advice (I’ve not got the grades for that), but I can tell you what I would do. If I were making a £30,000 short film, then the FTR could be worth around £6,000 to me. In order to prove my legitimate intention for theatrical release, I would book a week’s run in a cinema which has shown short films before (i.e. Picturehouse, Curzon, etc) for a year or two from now. I would also draw up a marketing plan and put some money aside for a P&A fund. I only need a short slot in the cinema each day so I’m sure I could agree a good price.

A few years ago, I showed that only 19% of UK micro-budget feature films reach a cinema in any country. This means that my hypothetical short film is in a much better place than four out of five average UK micro-budget feature films. Hell, I could even start pre-selling tickets to the public if I felt the need to further prove my real intention. I’m sure I could find a few people to buy them.

Another possible route would be to join forces with other short filmmakers, and create a portmanteau feature film, as happened with five Scottish shorts (Monkey Love Experiments, As He Lay Falling, Wyld, Exchange and Mart, and Seagulls) in 2015.

Considering how easy this is, and how much money could be at stake, I’m surprised more short filmmakers aren’t taking advantage of the FTR.

Tips on claiming UK tax relief for short films

Now that I have a database of UK short films that have claimed the FTR, I reached out to the filmmakers. Here are a collection of tips from short filmmakers who have successfully claimed money back for their short films, via the FTR:

“The main hurdle is showing that they are capable of theatrical exhibition. All you need for that is a DCP, which you can now make yourself, you don’t actually need it to have screened anywhere”

“The main hurdle is showing that they are capable of theatrical exhibition. All you need for that is a DCP, which you can now make yourself, you don’t actually need it to have screened anywhere”- “The first time I applied for the tax credit I was incredibly sceptical that I could actually get it, so I kept it out of my finance plan and intended to use it towards festival/marketing costs if it went through. It was a little unclear as to whether we would actually be eligible, but from what I had heard the key criteria was to be intended for theatrical distribution. All shorts are intended for theatrical distribution via film festivals, but in addition, my film had a guaranteed screening as part of the funding initiative it was financed through… so I felt relatively confident that I had a strong case. After going through the cultural certificate process we were approved by the BFI, which gave me more confidence that it would go through – but to be honest, it wasn’t until after my accountant filed the return and the money actually arrived in my account that I really believed it! I didn’t have any pushback from HMRC… We received just over £7,000 for a film that was roughly £32,000 budget.”

- “It took around 4 weeks for the film to receive it’s Cultural Certificate after I applied (it’s worth noting I also did apply for an interim certificate first before the film was completed, in an attempt to expedite the process and also give me an indication of whether we were going to be approved). My accountant prepared the paperwork shortly after, I think it was a few weeks of us going back and forth on a few things, and it ended up getting lodged about a month after we got the certificate. It was supposed to take 6-8 weeks to land in my account but I think it was actually more like 10-12 weeks. So I guess you could say it took around 5-6 months in total”

- [We had] “a slight shortfall from the full 20%… we could have claimed because we lost some art department receipts – so there’s a lesson!”

- “Keep a very detailed cost book of all your expenditure on the film. My Production Managers and I logged every single cost in a large excel spreadsheet and saved all the invoices/ receipts electronically into folders. You need this information if HMRC ask for it, its a lot of work so best to do it as you go rather than trying to get everything organised from a mountain of receipts at the end! This is also a good practice to get into for moving into features too”

- “Start the ball rolling early, and apply for your interim and final cultural certificate from the BFI as soon as you can”

- “It’s important to have a look at the cultural test if you are thinking of applying for the tax credit so you understand what criteria need to be met. In both my cases, the film passed the cultural test and earned all its 18 points in Section A, that is the nationality of the filmmakers, the nationality of the characters, the location of the story etc.. This is the ideal scenario for a short because it avoids needing an expensive audit of the film and makes things a bit more straightforward for the BFI team too”

- “As with features, the short must be intended for theatrical release. [Film 1] had already screened to a paying audience at the time of application so this was straightforward. With [Film 2] we had just submitted to festivals and as yet hadn’t been selected for any, so we said this was the plan to the BFI certification unit and they approved it. If you are planning to put the film online without a theatrical run you cannot claim the tax credit”

- “Have a conversation with your accountant as to how much they will charge for preparing this return for you – make sure you allow for this in your budget”

- “I do recommend that filmmakers apply – for me it was absolutely worth it, although I did treat it as a little bit of a gamble. Now that I’ve done it once I’m confident I can do it again. I wish there had of been more clarity around it just to give me a little more assurance that I could definitely receive the tax credit, or that I had of been able to speak to a producer who had successfully done it before”

Should you apply for tax relief for your short film?

You should only consider applying for the FTR is you meet all of the requirements below:

You are genuinely making a short film in the UK

You are genuinely making a short film in the UK- You have a legitimate intention for the film to get a theatrical release. Be prepared to prove this – just saying “I reckon it will” won’t cut it!

- You have the time to take this seriously. You should see this as an investor who is providing a fifth of your money. If this were a person, you’d take the time to ensure they got what they wanted and you’d take seriously any concerns they have. Don’t be slapdash with your applications to the BFI and HMRC.

- You do your research. Read the rules for the Cultural Test and for the Film Tax Relief before you start. Make sure you’ll qualify and that you prepare anything you need to. This could include ensuring you have enough money to produce a DCP when the film is complete.

- You are running the film through a limited company, which is registered for Corporation Tax. There is a provision in the law which states that if you take the FTR as a deduction on a Corporation Tax bill (rather than as a cash rebate) then you’ll get slightly more back. Therefore it may be worth finding an active limited company to partner with, rather than setting up a new company.

- You are going to employ the services of a professional accountant, ideally one who knows about the FTR.

- Your budget is large enough. There is no official budget requirement in the law (in theory you could apply for FTR for a £5 short film if you can prove it’s good enough to get into cinemas) but you’d only receive £1 back. This would be dwarfed by the accountancy fees and DCP production you’ve racked up in the process. My personal suggestion would be to ensure you’re spending at least £5,000 on the Core Expenditure to make it worth your while.

- You don’t need the money upfront. The money will not be available when you’re making the film, so you’ll either need to borrow the money in the short term or plan to spend the FTR cash after the film is complete, such as on your festival run.

What should you do with the money you get via the FTR?

On the face of it, this section has a silly heading – the money comes back as a rebate to the production company and they can then do whatever they want with it. However, some of the bigger short films will have been funded (entirely or in part) by funding schemes and local bodies. In these cases, the filmmakers may have agreed to share any income the film generates. The vast majority of short films generate zero income and so these clauses are usually there just in case the film wins an Oscar.

On the face of it, this section has a silly heading – the money comes back as a rebate to the production company and they can then do whatever they want with it. However, some of the bigger short films will have been funded (entirely or in part) by funding schemes and local bodies. In these cases, the filmmakers may have agreed to share any income the film generates. The vast majority of short films generate zero income and so these clauses are usually there just in case the film wins an Oscar.

However, if a producer successfully claims money back via the FTR, is this money ‘income’? If so, they may have to give some or all of it to their original funders to repay the initial funding.

I reached out to a few of the public bodies who support shorts and the general consensus is that they don’t regard FTR as income, but some used to. Jo Cadoret, Producer of Film London’s Short Film Schemes, said:

We don’t recoup on our awards currently. We did have 50% recoupment on awards during the UK Film Council years on UKFC Digital Shorts. Very few filmmakers got a return and it broadly disincentived them from seeking sales. It made sense when “Short Circuit” a company set up to distribute the best of UKFC shorts was in place, but that company did not survive past 2005.

I also asked Jo how many Film London-funded shorts had claimed the FTR. He said:

We don’t track this but on an annual basis out of 20 films maybe 2 films max propose this during the project development phase. Whether this translates into a successful claim is currently unknown.

Northern Ireland Screen said they were only aware of one of their short films having applied for the FTR. In answer to how they see their income, they said:

We would look upon the tax relief as the production’s investment in the film, not recoupment monies, although there haven’t been many examples of shorts who have been in receipt of the tax credit.

Nonetheless, it’s worth bearing this in mind if you apply for the FTR. You don’t want to be accidentally hiding revenue from parties who are entitled to a share.

How much could British short filmmakers be claiming?

To end this piece, let’s indulge in a bit of wild speculation (come on, you know you want to…)

Last year, Elliot Grove kindly gave me full access to the data behind the long-running and well-established Raindance Film Festival. Using this, I took a look at the self-reported budgets of the British short films submitted to Raindance in the past three years. 39% of British short films submitted to Raindance were reporting a budget of at least £5,000.

I zeroed in on all the British films made on at least £5,000 (the minimum level I think it’s work trying to claim tax relief from) and found that their combined budgets came to £22 million. If we assume that all were eligible for the tax credit and that 100% of their budget would fall under Core Expenditure, this suggests that £4.4 million could have been claimed by just the British short filmmakers submitting to Raindance. The figure for the UK industry at large is likely to be a lot larger.

Notes

There are a few details and caveats to bear in mind:

I am not a lawyer nor an accountant and you should always seek professional advice before making plans. To the best of my knowledge, this article is up-to-date and accurate, but I cannot be held responsible if you make a claim based solely on a blog article. There are a plenty of great film accountants in the UK who would be happy to help with your claim, to ensure you’re doing everything above board and correctly.

I am not a lawyer nor an accountant and you should always seek professional advice before making plans. To the best of my knowledge, this article is up-to-date and accurate, but I cannot be held responsible if you make a claim based solely on a blog article. There are a plenty of great film accountants in the UK who would be happy to help with your claim, to ensure you’re doing everything above board and correctly.- Tax records are private so we can only look at which short films have passed the Cultural Test, rather than those that received a tax rebate. Therefore, it’s possible that some of the shorts have passed the test for reasons other than claiming the FTR. If this is the case, then the number of successful short film claims will be lower than stated above.

- Most of the filmmakers I contacted were keen to chat privately but not to have their names published. It seems that because few shorts claim the FTR, some filmmakers worried that they had done something dodgy and didn’t want to draw attention to themselves. Bear in mind, these are the same people who hired professional accountants, sent off details of their plan to the BFI and then applied directly to HMRC – if they were doing something dodgy, they wouldn’t have been sent a cash rebate! Nonetheless, I understand their reticence and I was very grateful for their off-the-record candour.

- The exact percentage of Core Expenditure you can claim back via the FTR is a little more complex than just “20%”, as it is slightly higher if you’re offsetting the FTR against Corporation Tax owed, rather than asking for a cash rebate. This is a minor detail in the content of this article, so I’ve hedged my bets and referred to the FTR as providing “around 20%”.

- For today’s research, I counted a short film as having a running time of 60 minutes or less. That said, the vast majority were much short than an hour – the median running time of Raindance short submissions was 13 minutes and 30 seconds. Half of all submitted short films were between 7 and 15 minutes long.

- My wild speculation at the end is meant to be a fun exercise, rather than a scientific investigation. At each stage, I did my best to get to the true figures, but there are a number of hidden and unreliable variables so it’s possible that my final conclusion misses reality.

- Short film budgets are hard to study because of:

- Variation – They can differ hugely depending on the nature of the film and filmmakers.

- Gathering data – We are reliant on people self-reporting their budget, which also means that we are relying on their honesty. Three years ago, I used UK data to look at whether UK filmmakers lie about their budget (spoiler: at least 30% do) and last year I showed how the reported budget for Hollywood blockbusters is on average 12.5% lower than the true cost.

- Calculating value – Should we be measuring hard cash spent or value consumed? For example, if someone works at a kit hire company then they are likely to be able to access tens of thousands of pounds of equipment for next to nothing, whereas another filmmaker may have to pay the list price.

- Withoutabox only tracks budgets in US dollars so I converted them to pounds at the date of submission. FilmFreeway reports budgets in their original currency, meaning I didn’t need to do any conversions.

- When I started looking into this in earnest I reached out to the BFI for comment and extra data. They were very friendly and gave me annual numbers for short films passing the Cultural Test. These differ ever-so slightly from my own research, but I suspect this is just a data-gathering quirk. Some projects that are intended to be features may end up as shorts, meaning that the BFI tracking database still has them listed as features, whereas my research was conducted after the films were released and so would correctly show them as shorts.

Epilogue

I’m extremely grateful to the filmmakers who spoke to me about their experiences. The original data that allowed me to track down the short films came from the BFI and the Research Unit were particularly helpful in this research project. I’ve wanted to cover this topic for a while, so it’s pleasing to be able to finally share it.

I’m extremely grateful to the filmmakers who spoke to me about their experiences. The original data that allowed me to track down the short films came from the BFI and the Research Unit were particularly helpful in this research project. I’ve wanted to cover this topic for a while, so it’s pleasing to be able to finally share it.

The final note is one of caution. Filmmakers are right to claim what they’re entitled to, but we also have to be careful not to encourage frivolous or false claims. When I interviewed Dave Morrison from Nyman Libson Paul for my original Moviescope article he put it like this:

The Government will change the rules if they feel that there is abuse. I think they want to fund commercial movies rather than hobby filmmaking, so they are likely to tighten up on the type of short they accept if there are large numbers. This may mean new rules, but is more likely to manifest in rejected claims in the shorter term

Comments

Enlightening, as always, and enhanced by crowdsourcing some very useful tips.

I hope the BFI will commission you to do a proper survey of UK short film production some day, looking at its effectiveness for talent and skills development, exposure etc. That might become an important contribution to the ‘film school or short’ debate.

Looking at the time and/or fees required to service the FTR, it would be useful to get more detail how much should be allocated for this and if this is indeed worthwhile below e.g. 20k (or your cousin is a film accountant)? And did anyone consider approaching an accountancy firm with a ‘pack of short films’?

Just to note that the tax relief is capped at 80% of your core expenditure in the UK. I asked an accountant and they said for safety to add the FTR to your finance plan at 15% of your total UK spend. Also, a fee I was given to do the paperwork was starting at £750 for a feature production.

Hi Abi. Its 25% of 80%, meaning that in practice it works out just under 20%.

Do you have any video of that? I’d want to find out more details.

I don’t understand – video of what?

Hi Stephen,

I’ve just found your site and must say it’s exactly what I needed to see as we go into the next phase of production for my short film.

Regarding this article though – am I right in coming to the conclusion that if you already have a production company set up (even if it produced 0 revenue), we are eligible for the corporation tax relief?

Hi Efosa. Glad it was useful. Yes, if you have a Limited company in the UK then you will already be filing Corporation Tax returns each year.

This is really interesting – is an SPV required for tax credit for a short film?

No, you need to run it through a company which files corporation tax returns (ie all of them) but this can be an existing company.

In fact, if you apply for the tax credit via a company which made a profit that year, then you get a slightly higher % in the tax credit calculation, meaning a bit more money back.

How does it work if we are students at a film school, we are making the film outside of uni using our own savings, do we ask the film school to run this through them and them to send us the money afterwards or would they say no/ keep it all themselves. we are 18+ but do not have our own production company yet. Is this still possible?