Today, I’m sharing another project I carried out for the American Film Market along with Bruce Nash from The Numbers. In this article, we’re going to look at the performance of dramas, and what it takes for them to be successful.

Today, I’m sharing another project I carried out for the American Film Market along with Bruce Nash from The Numbers. In this article, we’re going to look at the performance of dramas, and what it takes for them to be successful.

The moniker ‘drama’ is often maligned by distribution professionals as not being a real genre. There is some truth to this claim – many films which lack a clear genre are simply labelled as dramas, and drama is a rather broad classification (i.e. any moment in life can technically be labelled as drama, whereas not every event can be classed as romantic, sci-fi, western etc).

The main purpose of genre classification is to set the audiences’ expectations. What will they get in return for their money and time if they decide to watch your movie? In the case of a comedy, they will expect to laugh. A horror movie promises to scare and/or unsettle. What does a drama promise to deliver? Merriam Webster’s dictionary suggests that drama movies “tell a story usually involving conflicts and emotions through action and dialogue” and often have a “serious tone or subject“. Whilst this isn’t an “official” definition for the film industry, it’s a handy rule of thumb.

Now that we know what we’re studying, let’s dive into what the data told us. We looked at four questions:

- What’s the most important factor affecting the success of a drama?

- What other factors correlate with successful independent dramas?

- Do film festivals favour dramas?

- Does star casting matter for independent dramas?

1. What’s the most important factor affecting the success of a drama?

Drama producers typically have low budgets and compete in a crowded market with little-to-no marketing support. So any competitive edge they can carve out for their movie will go a long way. The good news is that there is one factor which, above all others, correlates with success.

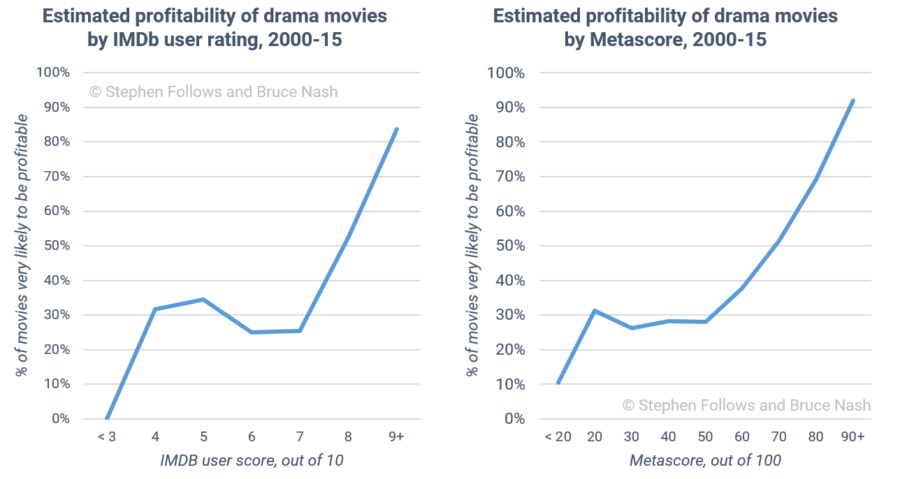

To discover this we looked at 1,604 drama feature films released in US cinemas 2000-15 for which we have production budget information (a complete list can be found here). By using an algorithmic model we’ve developed from real-world data, we were able to estimate the chance that each of our films reached profitability. This takes into account all income streams (from theatrical right through to syndication) and all costs (such as the budget, marketing and distribution costs).

We then studied the correlation between profitability and the views of film audiences (as measured via IMDb user scores) and film critics (as measured by a movie’s Metascore).

The results are pretty stark. Dramas with low scores perform poorly, whereas highly rated films are far more likely to be profitable. If your drama reaches cinemas with an IMDb rating of at least 8 or a Metascore of 70 or above then it’s more likely than not to generate a profit.  To some, this may seem self-evident but this isn’t the case for all genres. For example, horror films have a much weaker correlation between quality and profitability.

To some, this may seem self-evident but this isn’t the case for all genres. For example, horror films have a much weaker correlation between quality and profitability.

Also, the shape of the graphs are important. Improving films from being ‘ok’ to ‘good’ won’t help much – it’s get really, really good or go home!

2. What other factors correlate with successful independent dramas?

So, quality matters. But what other factors go into making a drama relatively successful?

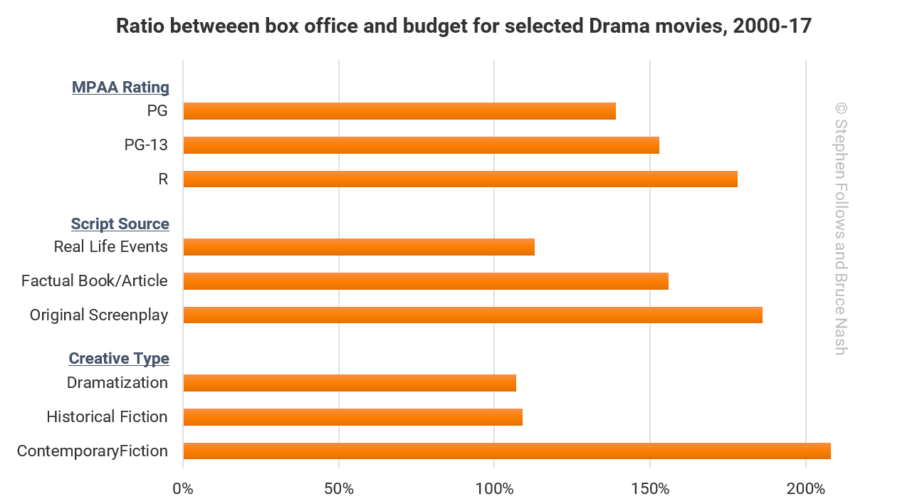

Looking in The Numbers’ dataset, we pulled out all US-produced dramas made since 2000 with a budget less than $10 million that received a theatrical release and examined the ratio between their domestic box office and production budget.

In order to avoid skewing the data too much, we excluded films that grossed more than 10 times their budget, and the ones that grossed less than 1% of their budget. (The total sample size after applying these rules was 228 films.)  Contemporary fiction generates the best box office return among creative types, with nearly double the return of historical fiction and dramatizations.

Contemporary fiction generates the best box office return among creative types, with nearly double the return of historical fiction and dramatizations.

Does this mean that contemporary is twice as popular among audiences? We don’t think so. Instead, we think that historical fiction and dramatizations (which by definition are also set in the past) are more expensive to make: think of the props, staging, period-appropriate vehicles, and so on. That doesn’t mean that films set in the past can’t be successful—far from it—but setting a film in the past for the sake of it probably isn’t a good idea.

Among sources, original screenplays perform slightly better than films based on fictional books, and better again than films based on real-life events (a category that includes films based on factual books). This is probably related to the expense of making films set in the right time period again, but another possible factor is that the author of a book isn’t constrained by thoughts of how much their creation might cost to film. If a pivotal scene in a book takes place in a snowstorm, a film adaptation of the book will probably need to include a snowstorm… and the expense that goes with shooting it.

For MPAA rating, there’s less of an effect. R-rated films tend to do slightly better than PG-13 rated films and PG-13 slightly better than PG. But the difference isn’t so great that we would assign a particular weight to one rating over another—it’s probably better to make the film authentically, rather than worry about adding or removing particular content.

This isn’t true at higher budgets (which is why virtually all studio films are PG or PG-13), but for independent drama, the target audience is over 18, and most likely isn’t basing its movie-going decisions on the rating of a film.

If you’re starting from scratch, this analysis suggests that contemporary, R-rated, original screenplay dramas perform slightly better. But there are huge variations for individual films, and, digging a little deeper, there are really a few rules that stand out:

- Be mindful of budget, particularly when it comes to the need to set a film in a particular time period.

- When adapting existing material, is there something intrinsic to the story that might be expensive to shoot?

- If your target audience is the adult demographic, don’t worry too much about keeping your film PG or PG-13 rated, but rather about telling the story authentically.

3. Do film festivals favour dramas?

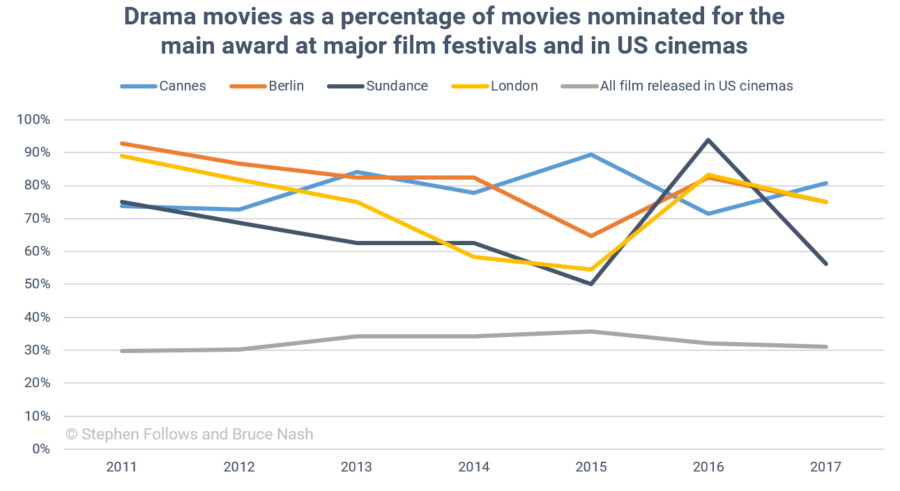

Film festivals are often seen as a vital conduit for drama filmmakers, a place where they can show off their new films and attract distribution offers. The data certainly backs the notion that dramas perform better than other genres at major festivals.

We looked at the nominees for the main film prize at four film festivals – the Cannes Film Festival, Berlin Film Festival, Sundance Film Festival (Dramatic competition) and the London Film Festival.

Across the seven years we studied, 76% of nominated films were dramas, as were 86% of the winners. By contrast, only 33% of the films released in US cinemas in those years were dramas.

4. Does star casting matter for independent dramas?

One final question we wanted to answer was whether casting a well-known actor or actress in an independent film has a significant effect on the film’s performance.

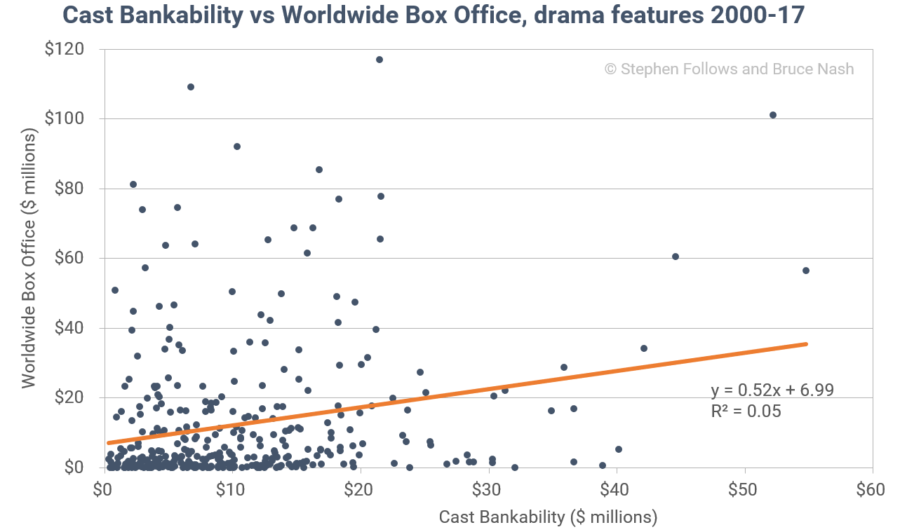

For this, we looked again at films budgeted between $1 million and $10 million, made since 2000, and with some reported box office, and used The Numbers Bankability Index to measure the star power of each film.

We used the simple measure of adding together the “per movie value” of each actor in a film, according to the Bankability Index, with no weighting for whether they had a starring or supporting role. This is a somewhat crude measurement but allowed us to get the widest possible set of films for the analysis—353 in total.  If there was a perfect relationship between Bankability and box office (e.g. every $1 of Bankability resulted in $1 extra at the box office), then the dots would line up roughly diagonally from the bottom left to the top right of the chart, but they look like a fairly random distribution.

If there was a perfect relationship between Bankability and box office (e.g. every $1 of Bankability resulted in $1 extra at the box office), then the dots would line up roughly diagonally from the bottom left to the top right of the chart, but they look like a fairly random distribution.

At the right-hand end of the chart, you can see that a really well-known cast in a low budget movie can make a difference: the three furthest points to the right belong to Good Night and Good Luck, Crash, and Dallas Buyers Club, all of which topped $50 million at the worldwide box office.

But if you look at the films that grossed over $100 million worldwide: Crash, Lost in Translation, and Billy Elliot, they had, respectively high, medium, and low star power.

So we don’t see a strong correlation between star power and box office performance. But there are other factors worth bearing in mind.

Having a well-known star can help secure international sales, or attract investors. And the analysis shows that stars do bring value to a project if only some. You can’t make a high-quality drama without high-quality acting… and we saw earlier that that’s worth paying for.

A note on drama definitions

In order to focus today’s research, we have used the classification system from The Numbers, which assigns only one genre per movie. This meant that 33% of the movies released between 1997 and 2016 were classed as dramas. The same figure for IMDb is 62%, meaning that they classify two-thirds of all movies as dramas.

Further reading

If you are interested in moving up the budget scale then you may enjoy one of my older articles which looked at the fate of $15 million to $60 million dramas over the past twenty years – Has the mid-budget drama disappeared?