In much of human life, we equate the length of time someone has been performing a task with their level of skill. Businesses proudly state how long ago they were founded, a lawyer with “30 years’ experience” can charge more than one fresh out of college and ‘time served’ often denotes seniority.

In much of human life, we equate the length of time someone has been performing a task with their level of skill. Businesses proudly state how long ago they were founded, a lawyer with “30 years’ experience” can charge more than one fresh out of college and ‘time served’ often denotes seniority.

But is this true of the film industry?

Put more directly, does the number of films a producer has made indicate how likely their next project is to succeed?

To answer this, I teamed up with Bruce Nash from The Numbers. We focused on 2,911 narrative (i.e. non-documentary) feature films released (either theatrically, direct-to-video or VOD) between 1999 and 2018. For each film, we have detailed estimates of their financial performance, allowing us to make a reasonable assessment of the project’s overall profitability.

We then looked back over the careers of all the main producers (i.e. everyone who received a ‘Producer’ credit) to determine how many feature films they had previously produced. Finally, we correlated this with return on investment (ROI) of each film.

How much experience does the average producer have?

To show levels of experience in simple terms, we have calculated an ‘Experience Score’ for each movie. This is the average number of movies previously produced by a movie’s main producers. For example, if a film has one producer who has previously produced two features, then this new movie has a score of ‘2’. Another film with two producers, one who had produced ten previous movies and another who is new to producing would have a score of ‘5’.

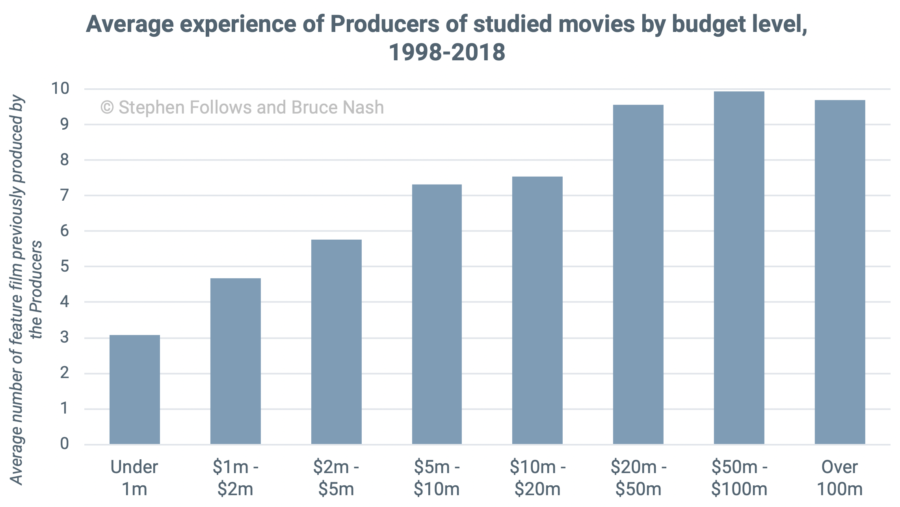

The level of producing experience on movies rises with the budget. On average, sub-$1 million movies had a score of 3 (meaning that on average its producers had previously produced three movies) whereas for movies over $50 million it is nearer 10.

Does prior producing experience help movies make money?

Now that we have a measure of experience, we can see how it correlates with financial performance.

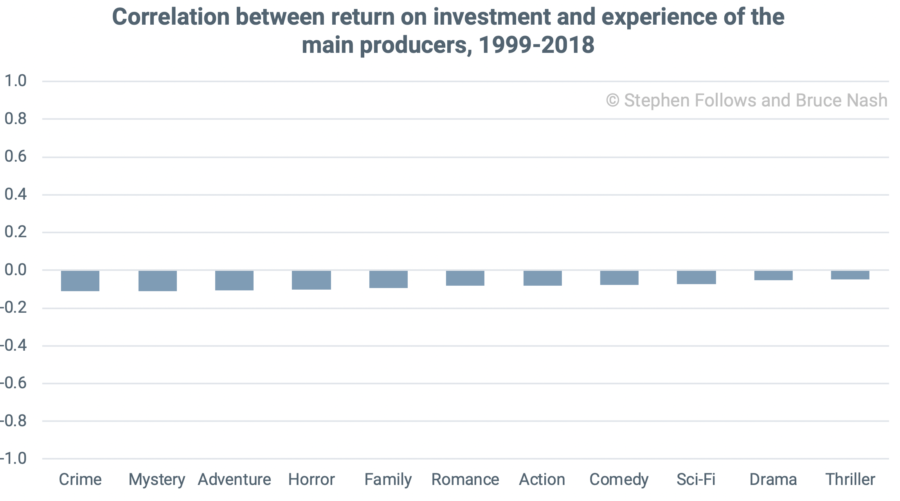

For each movie, we looked at the correlation between the return on investment (ROI) and the Experience Score of all the main producers. A correlation result of +1 would reveal they are perfectly positively correlated (i.e when one goes up so does the other) whereas a score of -1 would show the reverse (i.e. if one goes up the other goes down).

The answer is… when looking at profitability, experience counts for nothing.

In fact, it’s ever-so-slightly negatively correlated, with a score of -0.05 across the database (well within the margin of error).

What does this mean?

This result tells us that a producer’s experience doesn’t increase the likelihood of them producing profitable films. Why this should be the case is something we can only speculate about, but we have some ideas.

Firstly, the film industry has a weak feedback loop when it comes to profitability. If a film loses money, the producers behind it do not give up; they’re not ostracized; they don’t have their artistic licenses revoked. They may find their relationships with some of their investors become strained, but they can find new ones in order to continue making films. A good producer will know how risky the independent film business is, and they should be communicating that to their investors, so losing money on one film shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone.

Second, producers may get better at producing movies, but the profitability of the films themselves doesn’t change. For example, an experienced producer might be able to make more films each year, or negotiate better deals with distributors, thereby making more money for investors, even though the films themselves don’t earn more at the box office. Our analysis of films uses a consistent distribution model which wouldn’t pick up some of those subtleties.

Finally, it may be the case that a producer’s early films need to be better than average in order to get financed, so there are two factors that balance one another out: an experienced producer might be able to get more out of any given film, but an inexperienced producer is likely to have a better film in the first place.

Whatever the reason, the message here seems fairly clear: there’s no secret to producing movies that some producers know and others don’t. William Goldman may have said it best: “Nobody knows anything… Not one person in the entire motion picture field knows for a certainty what’s going to work. Every time out it’s a guess and, if you’re lucky, an educated one.”

Notes

In order to conduct this study, we began with a list of 3,217 films from The Numbers’ financial database, investigating full financial details, including North American (i.e. “domestic”) and international box office, video sales and rentals, TV and ancillary revenue. We narrowed our focus to study feature films released between 1999 and 2018. Finally, we calculated the likely profit margin for the producers, after all revenue and expenses were taken into account.

The financial figures come from a variety of sources, including people directly connected to the films, verified third-party data and computation models based on partial data and industry norms. It is possible that one or two of the individual figures are different to our predictions, though en masse we are confident of the larger picture.

During our research, we also checked whether this correlation is found when we just focused on the most experienced producer on each film. We found that the results mirror the average pan-producer Experience Score.

This research focuses on full ‘Producer’ credits, excluding other forms of credit such as Executive Producer, Associate, Producer, Co-producer, etc.

Comments

Thank you Stephen!

A great study as ever.

I think about another bias why seasoned producers might not make more profitable movies: Except for blockbusters (maybe), experienced production companies are used to minimize the seeming profitability of movies in order to minimize repayment and fees too, while newbies have to prove their worth (cf. Fox ‘Bones’ lawsuit.)

This might add to the reasons why seasoned producers are not ostracized for doing ‘less profitable’ movies.

That’s something impossible to statistically reckon of course.