A couple of years ago, I looked into whether erotic thrillers were indeed dying out or if it was just availability bias due to the fact that the main examples which come to mind are mostly from the 1980s.

More recently, Rachel Lloyd from The Economist asked me to look more deeply at one of the charts, which indicated a decline in the levels of sexual content in movies.

This prompted me to update and deepen the dataset to help us examine what’s happening and speculate on why. You can read Rachel’s article in The Economist here, and I’ll share the data below.

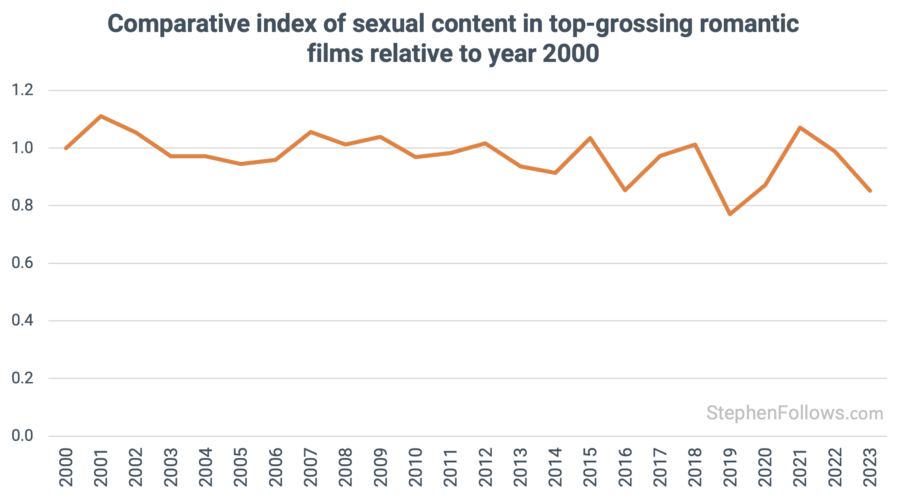

We looked at the top 250 grossing films of each since 2000, tracking the level of sexual content via signals from film rating bodies and film databases. There’s more detail on the methodology and criteria at the end of the article.

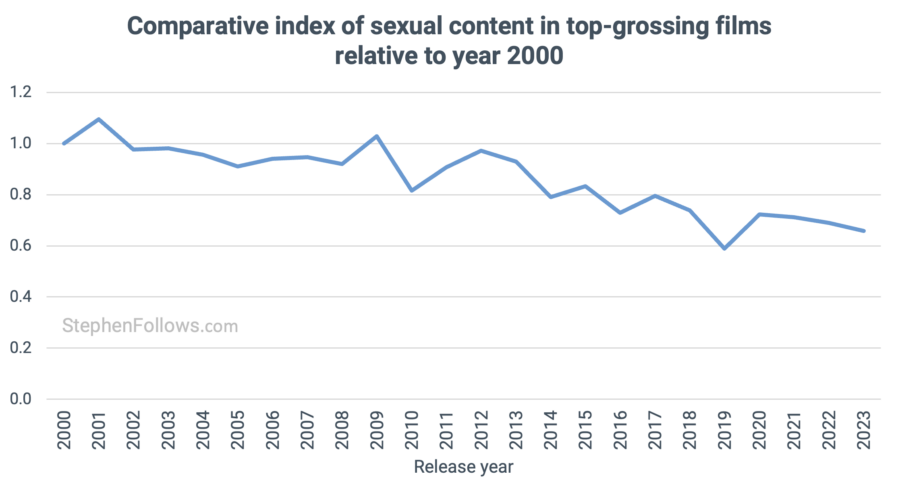

Over time, the sex declines

Comapring each year to the baseline of 2000, we can see a steady decline in the amount of sex in feature films. By 2023, it had fallen by almost 40% from the start of the century.

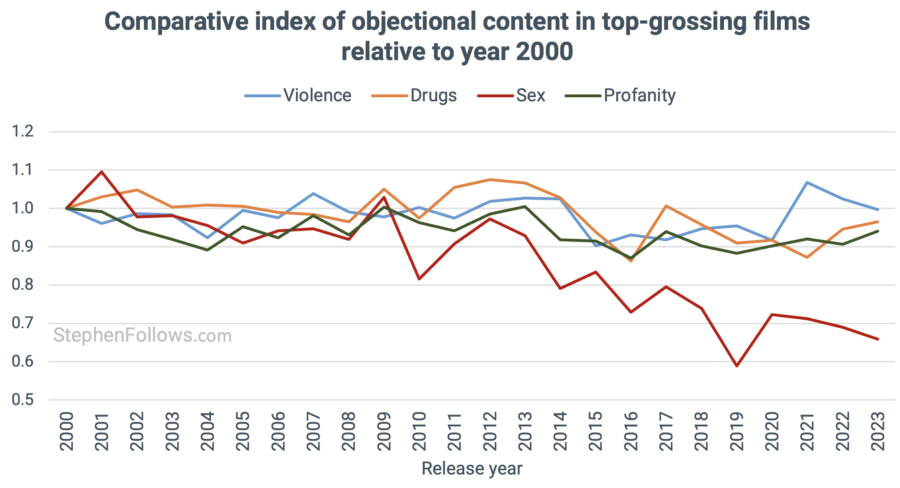

Are other ‘vices’ also declining?

In wanting to understand this better, the first thing we may ask is, ‘Are other types of ‘objectional material’ also declining?’.

Using the same method of looking for signals from ratings and feedback on the movies, we can be fairly sure that, no, levels of drinking, drugs, violence and swearing have not seen the same decline as sexual content.

What’s behind the decline?

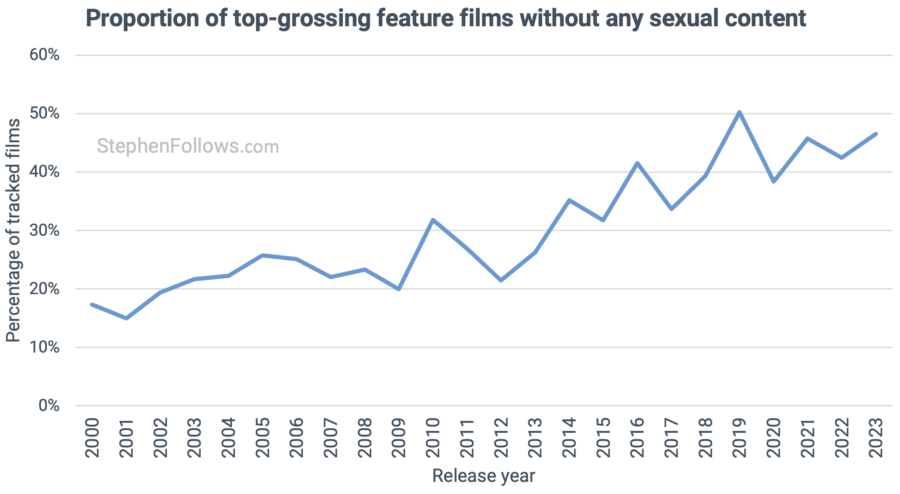

At this point, I’m sure you’re wondering if it’s a reduction in the intensity of the sexual content (i.e. the same number of scenes with sex, but at a more sedate level) or if it’s a case of fewer sexual scenes overall.

The answer is very clear – it’s the latter. The biggest driver of this reduction in sexual content across the board is the increase in the number of movies which eskew any scenes of a sexual nature. In short, there are more movies which are squeaky clean.

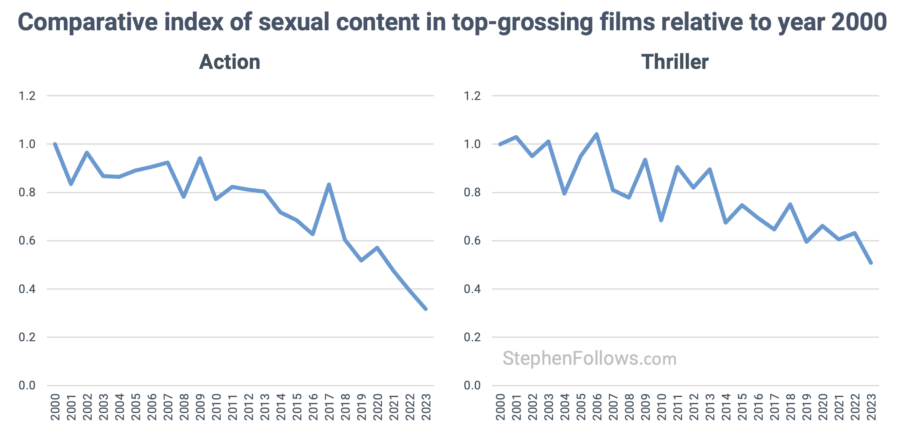

What types of films is this trend most apparent?

The declining trend is present in most movie genres, but it is most intense in thrillers and action movies.

And is least apparent among romantic movies.

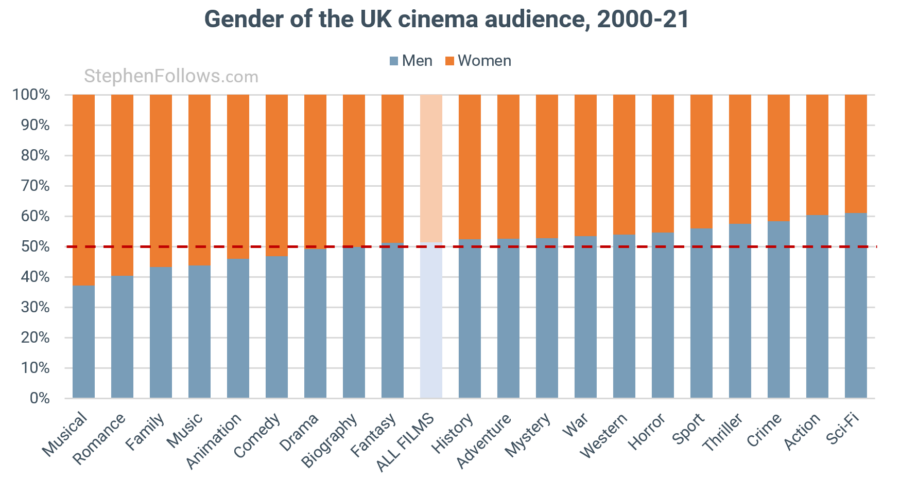

It’s interesting to note that the genres seem to correlate loosely with a previous trend I’ve discussed regarding the gender of film audiences.

The chart below uses comScore data, and reveals that thrillers and action movies have a slight male skew, and romance has the second-highest with a female skew.

So why is this happening?

The data can’t give us a single definitive reason, but there are a number of things we could suggest are playing a role:

- Changes in audience taste. Modern audiences, particularly younger ones such as Generation Z, might have less interest in explicit depictions of sexuality. Instead, there is a growing preference for content that either avoids sexual themes altogether or handles them with more subtlety.

- Shift in cultural norms. Social movements and heightened discussions around consent and gender representation have likely contributed to a more cautious approach to including sex scenes in films. Producers and filmmakers may be more sensitive to how sexual content could be perceived or potentially lead to controversy.

- Global market considerations. Films that perform well at international box offices tend to favour content that can translate across different cultural norms. Explicit sex scenes may result in more restrictive age ratings or censorship, hence reducing a film’s potential reach.

- The streaming age. With the rise of streaming services, which offer tailored viewing experiences, there may be less demand for sexual content in wide-release films. Niche productions and series on streaming platforms, where content can be more targeted and controlled, might absorb the demand for such material.

- Outdated stereotypes. The trend could also be a rejection of outdated stereotypes, where sex scenes were often objectifying and presented through a predominantly male gaze. Modern films may be attempting to depict sexuality in a way that’s more authentic and respectful. This feels particularly relevant when we think of “traditionally male-focused” genres, such as thrillers and action movies, as we saw above.

- The availability of adult content elsewhere. With the ubiquity of internet pornography, audiences seeking explicit sexual content have an abundance of options readily available online. This has potentially reduced the need for mainstream cinema to fill this niche, allowing films to focus on other elements of storytelling without the need to include sex scenes to attract viewers.

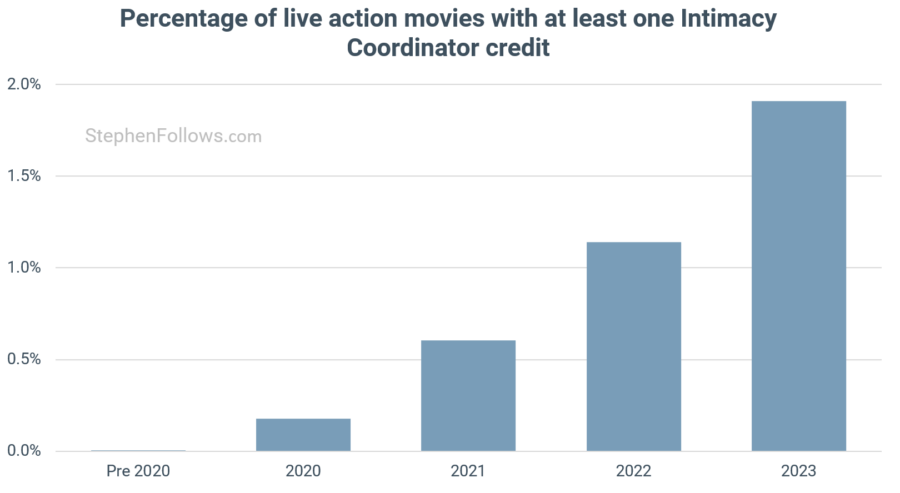

- The rise of Intimacy Coordinators. As the film industry addresses past issues of harassment and improper on-set behaviour, the role of the Intimacy Coordinator has gained prominence. Their presence could be discouraging gratuitous sex scenes unless they serve a critical narrative purpose. I looked into this a few months ago and below a key chart from that piece.

Notes

Today’s research looks at the top 250 highest-grossing live-action fiction feature films of each year, by Domestic box office. The raw data from a variety of sources including OMDb, IMDb, Wikipedia, Common Sense Media, Dove.org, MPAA and BBFC. I used these signals to build my own measures of sexual content in each movie.

I excluded films if their portrayal of sexual content was limited to sexual violence such as rape or sexual assault. This wasn’t a large number of films, but I felt it was important as there is a difference between sexual content designed to titillate and those designed to repel / disgust.

Today’s research was focused on high-grossing movies, as that was the criteria The Economist wanted me to study. However, when I looked at the trends across a wider selection of films, I found the same results.

The audience chart uses a binary conception of gender, as that’s how comScore has collected the data over that period.

Epilogue

The genesis of this article is one I really like. I had published the original chart showing the decline in sex last year, but I hadn’t twigged its significance. It would have languished as a footnote of the original article, had The Economist not reached out to ask for more details.

Not only that, but Rachel’s perspective on the topic improved and enhanced my reading of the data. You can read her article here.

Comments

Given the 9,956 genders, we’re supposed to have (and use) these days… I’m not surprised that things get… how shall I put this… difficult to portray in movies without “offending” one or more of these 9,956 genders.

Does this mean that The Economist will soon have a Page 3 girl?

Asexual – ultra violent society is the future … a long time after : make love not war !

I would be interested in linear regression analysis with 95% Confidence Limits around the curve. If you wish I can perform the analysis for you.

I am a retired Immunopatholigist and Biostatistician.

I would posit this has more to do with Studios producing for Streaming, esp. in the streaming wars.

Streaming companies so far want to be labeled as ‘family friendly’ and so not much salacious content is restricted. So an explanation might be that a movie with this content is harder to sell to streamers, and therefore studios focus on content that streaming networks will pay for.

Also curious– if this is only movies that had theatrical releases? Certain genres have had a very hard time in theatres since the streaming wars got going. Comedy, Romance, Drama– they are not putting in the numbers for box office revenue, so if the focus is top 250 by theatre revenue— how much is attributable to a drop off of certain genres in that list?

Could you clarify how you classified this. What do you mean by signals, the ratings given by the rating agency or textual analysis of scripts

Hi Ademola

Sure thing. I tracked a number of public data points and collated them into my own final measure.

In some cases they start out as numbers, such as sites which rate movies based on their content. Typically these are “family focused” sites who are looking to help parents understand what’s in a movie, in order to police what their kids watch.

In many cases it’s language based. Rating bodies tend to have a fairly constant, narrow lexicon they use to describe their reasons for rating a movie as they did. For example, the BBFC decribed Avatar thus: “moderate violence, threat, language”. Likewise, in the States, the MPAA added the following to the same movie “Rated PG-13 for intense epic battle sequences and warfare, sensuality, language and some smoking”.

Outside of formalised bodies, users can often submit their own thoughts on what a movie contains. For example, the IMDb Parents Guide provides readers with a breakdown of content, which is then up or down voted.

I weighted some of the sources as I found that the more informal an organization’s methods were (i.e. BBFC = formal / structured; vs IMDb = user generated) the more reliable it was BUT the less descriptive. I found a few (rare) cases of people acting together to add false data to IMDb and then upvote it. That wouldn’t happen with a professional reviewer or censor.

Oh this is quite an involved process. But I guess a clear dataset describing this phenomenon probably just doesn’t exist so this is really useful work. Even the BBFC rankings can be a bit vagues