In the final few days of 2018, UK retailer HMV went bankrupt for the second time in just under six years. This news led a few readers to get in touch with questions about the numbers behind HMV’s decline.

In the final few days of 2018, UK retailer HMV went bankrupt for the second time in just under six years. This news led a few readers to get in touch with questions about the numbers behind HMV’s decline.

The general tenor of the questions could be summed up as “Was HMV’s failure down to the industry’s move to digital delivery or to being more expensive than their rivals?”

It’s a fascinating topic and one which gets to the very heart of the changing face of the Home Entertainment sector, both in the UK and worldwide. We’re not going to be able to ascribe an exact percentage of HMV’s woes to each of the factors, but we can look at what the numbers tell us.

Let’s start with the simpler question of industry shifts, and then we’ll move on to how HMV compared to its rivals.

How the UK Home Entertainment sector is changing

HMV opened its first store in 1921 and, after an expansion in the 1960s, fast became a fixture on British high streets. It offered all manner of products including movies, music, games, merchandising, entertainment equipment, and more.

HMV opened its first store in 1921 and, after an expansion in the 1960s, fast became a fixture on British high streets. It offered all manner of products including movies, music, games, merchandising, entertainment equipment, and more.

They were a major player in the UK entertainment sector, selling 31% of all physical music in 2018 and 23% of all DVDs and Blu-rays. Its market share actually increased throughout 2018 but this was not enough to save the store from the massive shifts in the industry.

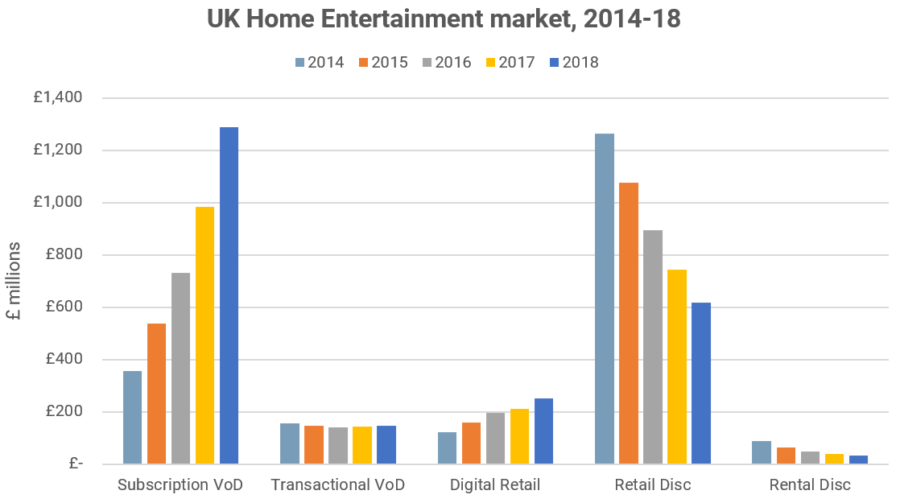

It’s not that consumers are spending less on home entertainment products – far from it. The UK Home Entertainment sector has grown by 18% in the past five years, from £1.98 billion in 2014 to £2.34 billion in 2018. But it’s where that money is going which has spelled double doom for HMV. Over that period, Subscription VoD sales have more than tripled while DVD and Blu-Ray sales are a third of what they were in 2014.

This falling tide sinks all retailers who rely on physical sales, no matter if the company is dead wood or solid as oak.

HMV’s physical presence on the high street only exacerbated their problem as it made them far less able to respond to the shifting market than an online-only retailer. They couldn’t reduce their wage bill without closing stores, they were chained to sites with high pedestrian footfall and had to hold far more stock across all their stores than an online-only operation which can despatch discs from a single warehouse.

So there’s no doubt that the writing was on the wall for the model HMV had relied upon for the past half-century.

Let’s now take a look at the other factor which readers asked about – HMV’s prices.

How competitive was HMV?

Towards the end of last year, I conducted an as-yet-unpublished study into the price of DVDs, Blu-Rays and digital movies in the UK. The data from this work is the perfect source for us to investigate how HMV compared to some of its major rivals.

Towards the end of last year, I conducted an as-yet-unpublished study into the price of DVDs, Blu-Rays and digital movies in the UK. The data from this work is the perfect source for us to investigate how HMV compared to some of its major rivals.

This data focuses on major movies (top 200 at the box office) over the past eighteen years and the lowest price at which the movie is on sale at each retailer. There is more detail on the methodology and relevant notes at the end of this article.

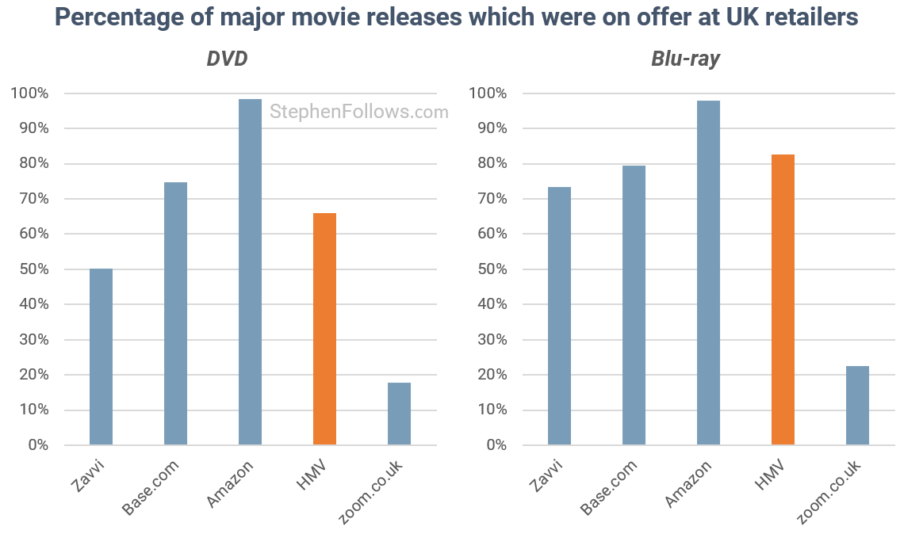

We’ll start with the breadth of inventory. It’s no surprise that Amazon offers the widest selection of movies, on both DVD and Blu-Ray. HMV carried two-thirds of available DVD titles and four-fifths of available Blu-Ray titles.

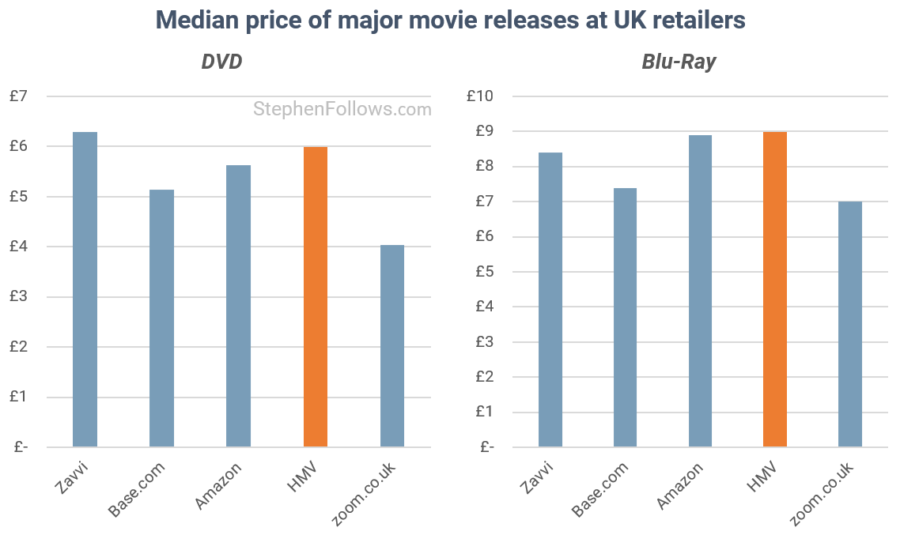

Looking at prices, the median price for a major movie DVD release at HMV (at the time of my research) was £5.99.

This is very cheap if compared to the industry average cost of a DVD in 1999 (£15.75) but slightly more expensive than most of their other rivals in 2018 (Amazon was £5.63, Base.com was £5.14 and Zoom.co.uk was £4.04). Only Zavvi had a higher median DVD price, at £6.29.

The picture was worse for HMV when it came to Blu-Rays, where they ranked at the most expensive of these five retailers, at £8.99.

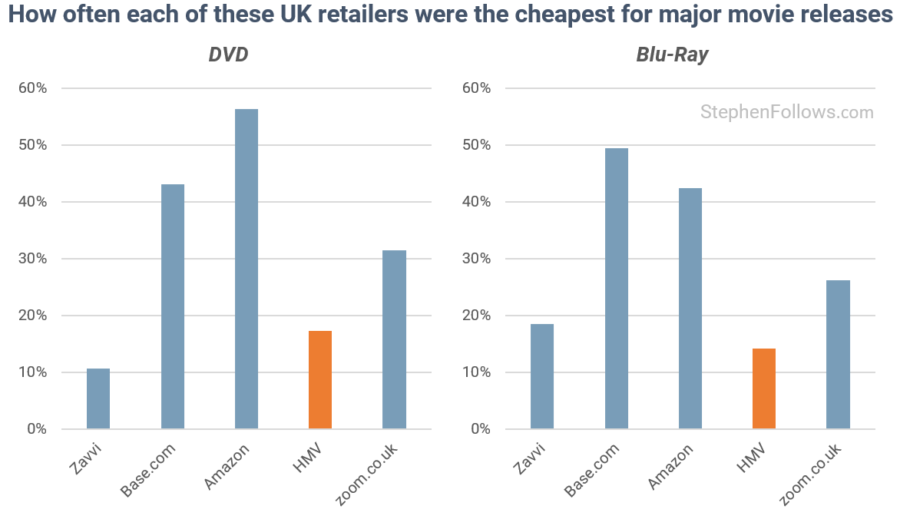

This meant that HMV was rarely the cheapest place for UK consumers to source their DVDs. Only 17% of DVDs were cheapest at HMV and only 14% of Blu-Rays.

Note: The charts above add up to more than 100% as often more than one retailer shared the same cheapest price for a title.

Conclusion

So I guess both of the readers’ theories were borne out, although to different degrees.

The major cause seems to be the shift from physical to digital ownership and the move away from single title purchases to subscription offerings such as Netflix.

But it’s also true to say that HMV was rarely the cheapest place to source your DVDs and Blu-Rays. The main weapon they had was their physical presence on high streets, but as more consumers shifted their purchases online, this factor became less of an advantage and more of a millstone.

Notes

The data on the sector came from The Official Charts Company, Futuresource Consulting, IHS Market via the UK industry body BASE (not to be confused with Base.com, one of the retailers studied and a wholly unconnected company). The prices came from each of the retailers, with help from FindAnyFilm to find listings.

The data on the sector came from The Official Charts Company, Futuresource Consulting, IHS Market via the UK industry body BASE (not to be confused with Base.com, one of the retailers studied and a wholly unconnected company). The prices came from each of the retailers, with help from FindAnyFilm to find listings.

I gathered the price data in October 2018. Throughout the year, prices fluctuate so it’s possible that the picture would have been subtly different had it been conducted in the Christmas period or the January sales.

I focused on feature films released theatrically between 2000 and 2017 (inclusive) and which appeared in the top 200 of the Domestic box office of each year. This was to focus the data on the most common titles and not to let it get swamped with TV series, low budget or straight-to-DVD titles. Many retailers offer more than one DVD or Blu-Ray version of a movie, either as part of a package or just different issues of the movie. In each case, I took the lowest price the movie was available at from that retailer.

The charts showing the percentage of movies on offer relate to movies which were available at any of the five retailers, not all movies made. This is so that it represents all the movies they could actually stock and excludes movies not available on DVD or Blu-Ray in the UK. Likewise, the cheapest price is of the five retailers, not of any retailer in the sector.

There are likely to be many other factors which contributed to HMV’s woes. I only present these two as (a) these were the ones I was asked about, and (b) these are two I have good quality data for. At the time of writing, HMV is still trading, under the bankruptcy guardianship of KPMG. I have used the past tense because my data relates to last year, not because HMV no longer exists.

Epilogue

Like anyone who was a child in the UK in the 1990s, I have fond memories of browsing HMV for movies. It introduced me to the joys of independent and cult movies as well as helping me pad out my collection of less highbrow content. But I don’t think I’ve been to an HMV in the past five years or longer, and I very rarely visit any retailer of physical content.

Like anyone who was a child in the UK in the 1990s, I have fond memories of browsing HMV for movies. It introduced me to the joys of independent and cult movies as well as helping me pad out my collection of less highbrow content. But I don’t think I’ve been to an HMV in the past five years or longer, and I very rarely visit any retailer of physical content.

This is yet another lesson in how quickly things can change, no matter how inconceivable a shift may seem. Companies like Blockbuster and HMV represented huge powerhouses and held dominant market positions. This means that we should not be so certain that the film industry of the future will be dominated by the major players of today.

Maybe in a decade or two, I will be writing about 2019 being the high point for Disney, before their decline, irrelevance and eventual bankruptcy. Or Netflix. Or Apple. Hard to even imagine, but history suggests it’s more possible than we might think.

Comments

“Was HMV’s bankruptcy down to industry changes or high prices?”

In a word – neither! HMV, along with all the other failing shops on the UK High Street are failing as a direct and unmitigated result of bad management decisions.

20:20 hindsight is always a fine thing, but we can now say that shop chain owners were too keen to sign long leases at high prices, councils levied business rates at unrealistic levels and made driving to the shops difficult or impossible and management just dug their heads into the sand and refused to do much or anything about changes in tastes and the on-line revolution.

In the specific case of HMV, new owners Hilco insisting on £48m in service charges didn’t help either.

It is not just HMV. I went into our local mall on the Tuesday before Christmas and both floors of our local Debenham’s (clothing) were completely without a single customer. Marks and Spenser (food and clothing) had a handful, but the food store had about 12 staff milling about, not doing much and jut six customers. In that particular mall and on that particular day, it was pretty much long faces all round.

HMV on that day had a few customers looking for something worth buying, but it soon became obvious that they were not finding anything that they wanted. Like Debenham’s and M&S, they are not offering anything unique or even especially attractive. Like Debenham’s and M&S, they are offering the same tired old hash everyone else has.

Because HMV has no unique content (thereby loosing out to Amazon Prime and Netflix) and a very poor on-line presence, there is no imperative to go to all the trouble of finding a parking space and battling into a town centre to visit their shops.

There is a lesson here for the movie industry! You had better wise up and start rejuvenating both your product and your structures. The new movie houses are in the living room. There are whole new markets opening up and for all demographic groups.