Earlier this month, Disney published release dates for their upcoming slate of movies, including their newly expanded roster of titles acquired when they bought rival studio Fox.

Earlier this month, Disney published release dates for their upcoming slate of movies, including their newly expanded roster of titles acquired when they bought rival studio Fox.

This included a domestic theatrical release date (i.e. when the movie will open in American and Canadian cinemas) for Avatar 5 of 17th December 2027.

Yup, the date has been fixed a whopping 3,144 days ahead of the actual release.

In many cases, the release date is literally the only piece of information revealed about an upcoming movie – even before the movie’s title. Disney’s future release schedule currently contains dates for 29 “untitled” films, including:

- Twelve movies called “Untitled Disney Live Action”

- Eight called “Untitled Marvel”

- Four “Untitled Pixar” (although only two of them are described as animations)

- Three “Untitled Star Wars”

- One “Untitled Indiana Jones”

- One “Untitled Kingsman movie”

This led me to wonder: just how far in advance do studios announce their movie release dates? And how often do those announced dates turn out to be correct?

To find out, I built a database of 8,324 release date announcements made over the past ten years, using the domestic theatrical release dates of feature films. See the Note sections at the end of this article for details of the data.

What are they announcing?

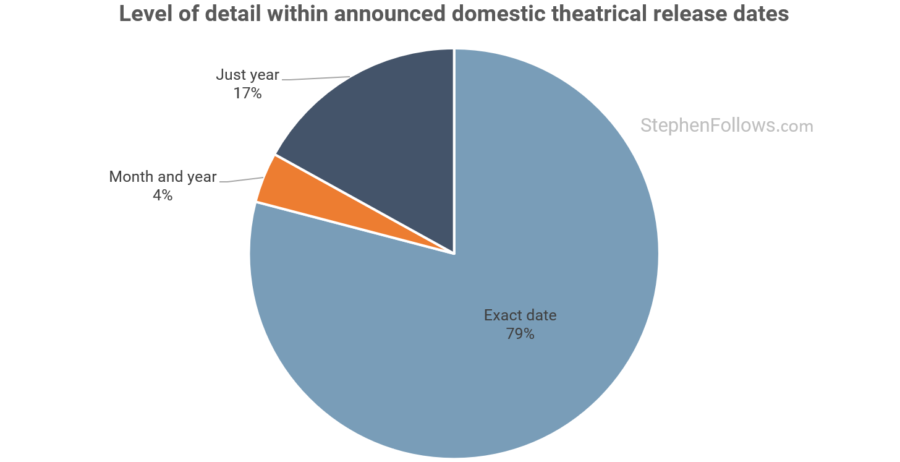

Let’s start by understanding what a release date announcement can look like. My full dataset includes three types:

- Just year. This is the vaguest of announcements, often reported by trade papers based on a comment or remark made during an interview with someone close to the production. For example, there is a new animated version of Super Mario Bros in the works and on 6th November 2018 Variety reported that the founder of Illumination Entertainment was quoted as saying that the film was in “priority development” and “could be in theaters by 2022“.

- Month and year. Other announcements come with an estimated month as well as a year. In reality, this isn’t giving a whole lot more information away, as movies are typically released in fairly well-defined slots within the year. (More on release patterns here and here). Almost half of Illumination’s past titles were released in June.

- Exact date. This is the studio or distributor announcing the specific date their movie will open domestically.

Nearly four out of five release date announcements are in the form of an exact date.

For the rest of this article, I’m going to focus on the 79% of announcements which specify a particular day in the calendar.

How far in advance are release dates announced?

Almost a fifth of release dates are publicly announced within a month of the film’s opening day.

This is not because the distributors or cinemas didn’t know the date before then, but just that there was no need to publicly promote it. The vast majority of cinema tickets are purchased either on the day of the screening, or a few days before. Tickets for high demand movies, such as Star Wars and Marvel movies, will go on sale in advance but not by much (Avengers: Endgame tickets were on sale just 23 days early) and this is for only a handful of movies a year.

20% of movie release dates are announced at least a year early, and within that, 2% are announced three years prior.

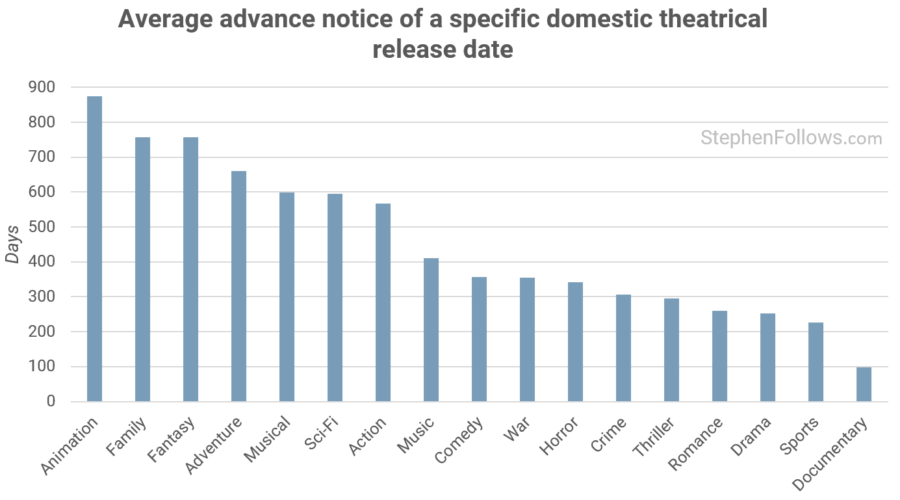

So far, I have been treating all movies equally, however, there is a huge difference between a big budget studio tentpole and a small indie flick with a limited release. If we subdivide the advance notice data by genre, we can see some very clear patterns.

Animations have the longest lead time – an average of 875 days. This is likely a combination of the big budgets needed to create modern animated movies and the fact that animations typically take far longer to make than live action movies (more on that here).

The genres with the shortest time between the announcement of a specific release date and said date were dramas, sports movies and documentaries. These types of movies typically don’t have big budgets, a large marketing spend or an existing support base, thereby reducing the utility of an early announcement.

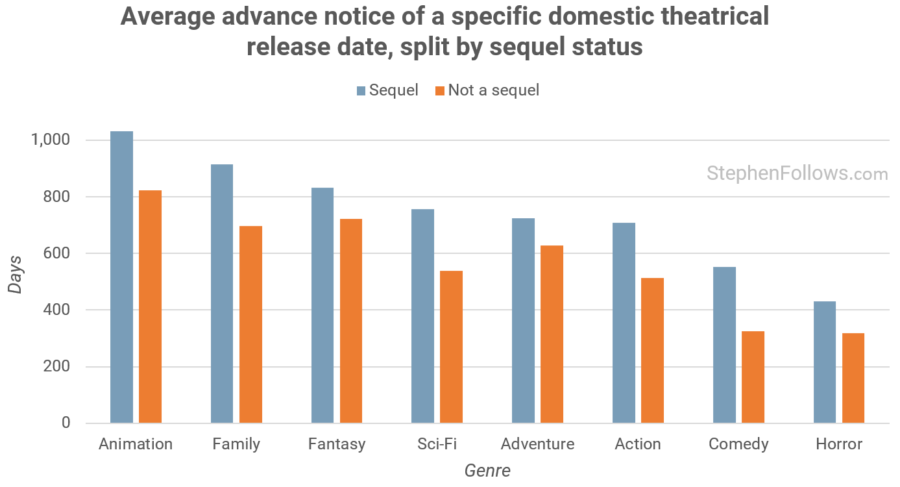

One other factor to bear in mind is how anticipated the new movie is. The easiest way of seeing this is with the announcement of release dates for sequels. Sequels are only created because the first movie was a financial success, meaning that it’s fair to assume that sequels, on average, command more public interest than non-sequels.

This is reflected in how early release dates are announced. In all genres (which had enough sequels to made the results meaningful), they are announced earlier than non-sequels, on average. In the case of comedies, it’s getting close to twice as early, with non-sequels being announced an average of 325 days before release whereas it’s 552 days for sequels.

Are early dates often correct?

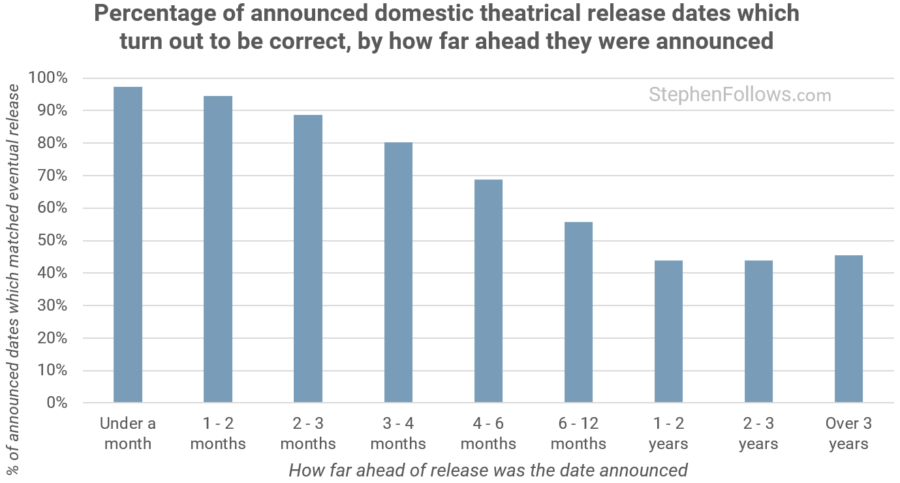

Given how far in advance some movies are confirming their exact release date, you may wonder how many of these dates turn out to be correct. If so, good news – I checked!

Unsurprisingly, the nearer the release date, the more accurate the information ends up being. Dates announced within a month are correct 97% of the time, compared with just 45% of the time with dates announced a year out.

Less intuitive is the flattening of the curve once we get past one year. This is a reflection of the fact that the vast majority of movies with such early announcements come from major studios. This is because:

- Studios have the infrastructure to plan this far ahead;

- They have the clout and money to scare off rivals who were previously eyeing up the same date; and

- They actually have a very small number of possible dates to pick from. In the case of Avatar 5, they are claiming the pre-Christmas slot which big budget movie franchises covet (i.e. Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit, Star Wars, etc) and so there were only maybe one or two other dates within 2027 that they could have selected.

Are they over- or under-estimating dates?

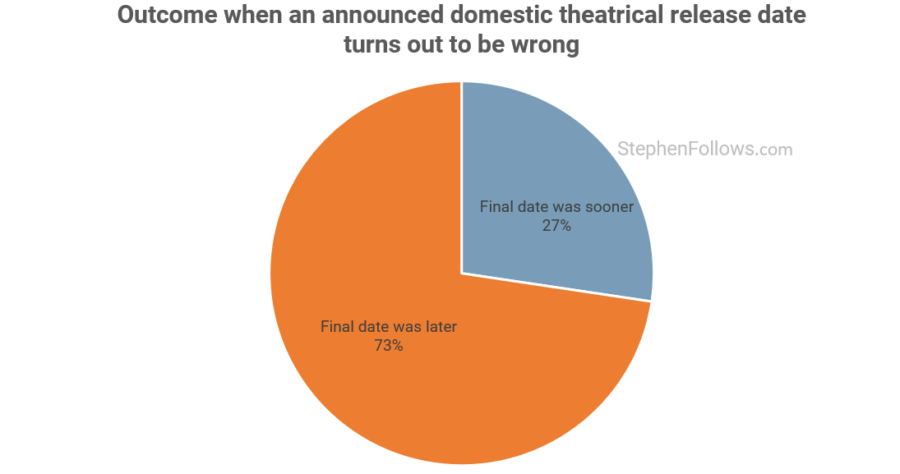

Finally, when movie release dates change, which direction do they tend to move in – sooner, or later?

In three-quarters of cases, when revised release dates are annouced they are later than the previous date.

Further reading

I have studied the topic of release dates a few times before, and so you may enjoy the following articles:

- Does Hollywood use the same movie release pattern every year?

- Are January and February Hollywood ‘dump months’?

- How far in advance are film trailers released?

- Three major ways movie release patterns are changing

- How long between UK and US movie release dates?

- How long does the average Hollywood movie take to make?

Notes

The data for today’s piece came from IMDb, Movie Insider, Wikipedia and The Numbers / OpusData (who have recently started offering access to their data on changing release dates).

All the release date announcements I studied were made between October 2009 and May 2019, inclusive.

Comments

Comprehensive data, thanks.

Thanks for the report. Some absurdity, however I found it an interesting survey.

Very interesting. Thank you, Sir.

Given how much our viewing habits have changed in the past five years and how significantly the once dominant position of cinema as the backbone of any movie has eroded I can not help but wonder if the release date is that important at all in the next 5 years, given that the majority of consumers will watch from the comfort of their home on a 16k 120″ television OLED screen.

Hi Jurgen. There’s no doubt that we’re in a time of change, and the increasingly high-tech options at home do threaten some major aspects of cinema viewing. But there are two which are not yet matched by home viewing – social interaction and event viewing.

Social interaction relates to the nature of cinema-going as a cheap, easy, low-commitment way of seeing friends, going on dates and whiling away an evening. The ‘event viewing’ aspect was on show with Avengers:Endgame where cinema websites were crashed by people trying to get tickets for the same opening weekend, and it ended up crossing over a third of a billion dollars just on the first few days and just domestically. The movie is going to be on iTunes in a few months for a similar price, and then free to watch on TV in the coming years. But the opening weekend was more about being part of a global cultural moment than simply having seen the film.

These facts may or may not allow cinema to remain the same, but I think they will go a long way to ensure it’s around for a while.

I’m all with you Stephen when it comes to the social aspect of watching a tentpole movie on a massive screen with a large number of people you don’t know (except the one who’s hand your holding) in a crowded darkened room.

However, this also defines – back then, now, and in the future – the type of movies suitable for cinema release and the age of the target audience. More ”sophisticated” content and genres (those without folks dressing in spandex) will be geared to home entertainment, or what we used to call ”direct to video” back in the days.