One of the features I love most about movies is their ability to give us shared stories which entertain, inspire and soothe us. And in trying times, this function becomes ever more essential.

In the 1940s, musicals provided a colourful escape from war, stories of rebellion in the 1970s gave hope to audiences losing faith in political systems and modern-day superhero movies provide easy delineation between good and evil in murky times. So what will be the escapism of the 2020s?

Regular readers will know that I subscribe to MGM co-founder Samuel Goldwyn’s belief that “It is difficult to make forecasts, especially about the future”. Therefore, I won’t pretend to know what the next decade holds for on-screen stories. But I do want to share something I found while playing around with a few of my movie datasets which I think may be relevant.

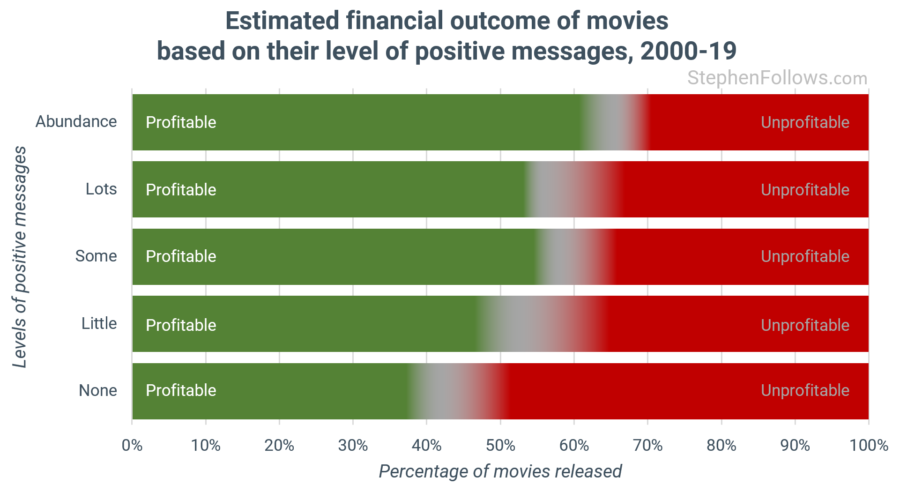

I studied the financial performance of 4,271 movies which were released in the past two decades and looked for patterns with their levels of positivity. Although positivity and positive messages are slightly nebulous concepts, we can track signals from a number of sources. For example, sites such as Common Sense Media provide breakdowns of the contents of movies to help parents make informed choices about what movies to let their children watch. There’s much more detail on my data and methodology in the Notes at the end of the article.

Do films with positive messages make more money than those without?

Let’s start with the overall result and then break it down by genre.

I used a mix of real-world data and algorithmic estimation of financial performance to look at the likelihood each movie was profitable. This calculates whether each film’s total income from all sources is likely to have outstripped its total expenditure associated with making and distributing the movie. This method results in a degree of uncertainty so in the charts below I have added a colour gradation between the two ends of the spectrum (i.e. “Profitable” or “Unprofitable”).

The charts below show the headline result. Across movies of all types, those with higher levels of positive messages are more likely to be profitable than those with less or no positive messages.

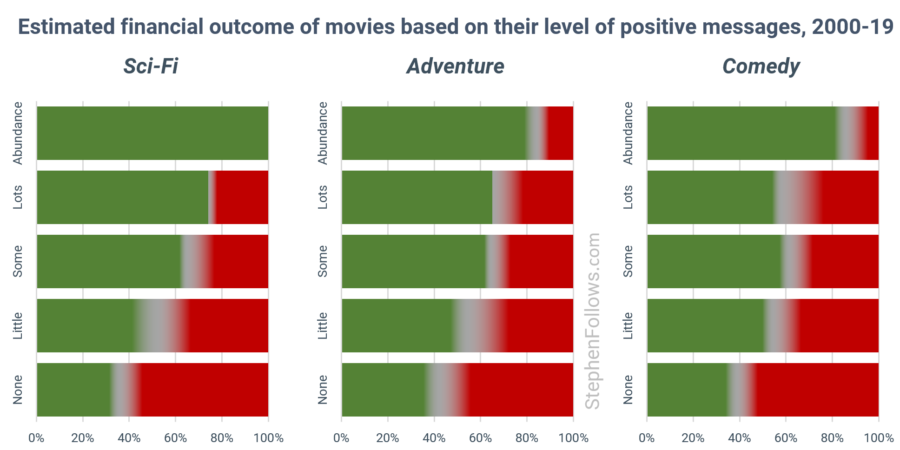

Which genres have the strongest link between positivity and profitability?

I have picked out three genres which seem to have the strongest connection between the two factors, namely Sci-fi, Adventure and Comedy.

It’s worth remembering that some genres are more frequently made than others, and also that the more we subdivide our categories, the greater chance we have of extreme results. For example, in the chart above, the Sci-Fi data relates to 492 movies but there are only a handful of “Sci-fi movies with an abundance of positive messages.” Therefore, if many more extremely positive sci-fi movies were made, I doubt it would maintain its “100% profitable” result.

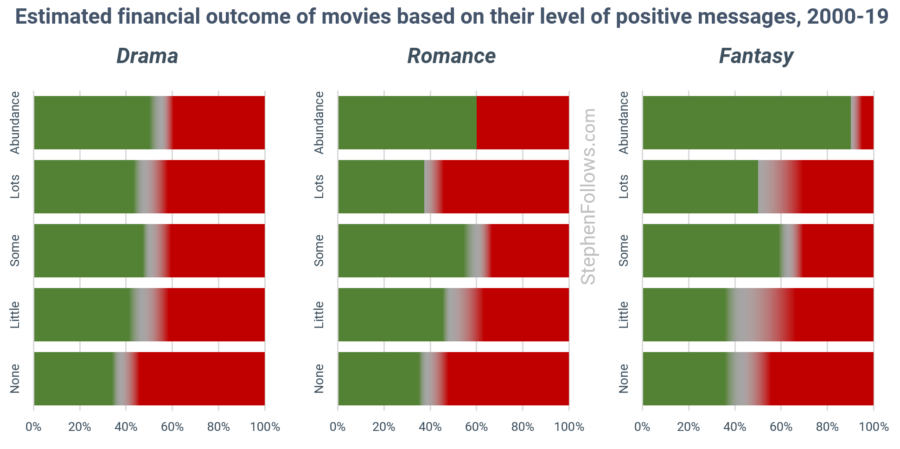

Which genres have the weakest link between positivity and profitability?

I could not find any genres in which the headline result was reversed, not even horror. That said, some genres seem to have a much more mixed result. The least likely to follow the “positivity equals profits” rule of thumb were drama, romance and fantasy.

If you would like to read more above movie profitability then you may enjoy these past pieces of research:

- How movies make money: $100m+ Hollywood blockbusters

- Do Hollywood movies make a profit?

- What percentage of independent films are profitable?

- How is a cinema’s box office income distributed?

Notes

The data for today’s research came from Common Sense Media, Dove, MPAA, BBFC, IMDb, OpusData and Wikipedia. It includes all feature films released in US cinemas between 2000 and 2019 for which a budget and box office data was available.

It’s worth stating the obvious that measuring the amount of positivity in a movie is subjective. It’s not possible to truly track an exact, unbiased level of content in a movie without many reviewers watching the same movie and having an objective standard for scoring. That said, the sources I used have clear guidelines as well as experienced reviewers who justified their scores and based them on a shared criteria. In the absence of a better measure of a movie’s content, this works well enough for the function needed in today’s research.

Profitability is also something which is hard to research, but for a different reason. While there is an objective truth to the costs and income of a movie, we have a hard time finding it out. Today’s research uses a mix of real-world data and calculations, based on standard industry practice. This is getting harder to do as more of a film’s value chain comes from the hidden worlds of VOD and digital sales, compared to the relatively transparent world of cinema admissions.

We’re measuring correlation, not causation. This means that we don’t know to what extent the positive messages are leading to the financial outcome or if there are other linked forces at play.

Epilogue

Today’s article sprung from a research dead-end. I thought I’d share the original idea to see if readers could help suggest next steps…

My wife and I have been re-watching various movies we remember from our teenage years and after a particularly explosive double bill (Demolition Man and The Running Man) I started to think about utopian versus dystopian Sci-fi movies.

I formed a couple of theories to test:

- That there are many more dystopian sci-fi movies than utopian ones. I’m reasonably sure this is the case, but of course, we can never know until we crunch the numbers.

- Utopian sci-fi movies are more successful than dystopian ones. This is more of a reach and might just be something I want to be true, rather than the actual truth!

However, in trying to conduct this research, I ran into two major problems:

- Who’s asking? The term ‘utopian’ refers to a world in which everything is perfect; a world beyond hardship, prejudice, injustice, etc. These are somewhat subjective terms and so utopia is in the eye of the beholder. The vast majority of people in Brave New World would consider their world to be utopian. However, as the book is told from the perspective of dissidents, we view it as oppressive and controlling. Likewise, the Wakandans in Black Panther, the Eloi in The Time Machine and the Borg in Star Trek may regard themselves as living in a utopian world/civilisation (certainly when compared to dystopian visions such as that shown in Blade Runner).

- What’s happening? Movies are about conflict – things need to happen, people need to overcome adversity and have something to strive for/against. Therefore, a story in a truly utopian world would be 90 minutes of people eating grapes. There must be trouble in paradise, and given the tropes of movie hero/ines, it’s likely that our main protagonists will reveal some nature of the utopia to be illusionary.

So I couldn’t think of a path forward for the research. If any of you can help, please do get in touch.

Comments

Thought provoking article Stephen which reinforces my own mantra that movies where audiences leave the cinema with a spring in their step generate much more positive word of mouth = bigger audiences. There’s a place for less positive, more downbeat movies of course, but if you want to make money from them then make sure budgets are low e.g. The Lighthouse with a budget of $4m and a box office of c.$20m = a financial success. And not like Nocturnal Animals which cost $23m and made c. $30m = bit of a financial flop.

As a semi-retired educator and lover of movies, I found your article fascinating for many reasons and on many levels that I will refrain from delineating in favor of asking more questions. First, would a franchise like the TAKEN series be, in your research, be considered POSITIVE because of the “Hollywood endings”? So the theme of retributive revenge is positive if the protagonist is a character we can empathize with and thus identify with? And Hamlet’s lack of ability to take revenge? Would that then be negative? In classes with teenagers these are not academic questions because “taking revenge” or justifying the means because of the ends is a problem that teenagers face regularly. Thus, I am thinking: the subjectivity of rating what is positive leads me to suspect that traditional ethical standards of a mature and positive society (e.g., revenge is not a positive value) may be at odds with our movie notions of a “positive theme.” Yes?

Hi Valerie

Great question. There is certainly a level of subjectivity to the notion of positive messages. The key thing which makes it useful is that it is consistent subjectivity. So if tune into the world of the sources creating the underlying data, we can get a better sense of what we’re seeing in the final results.

In this case, it’s bodies who are looking to provide parents with details of what’s in a movie, in the context of showing it to their kids. With this in mind, we can surmise that revenge would not be regarded as positive. And this is born out in such reviews – for example on Common Sense Media they regard Taken as having no positive messages. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/movie-reviews/taken

Interestingly, Taken 2 gets two out of five on their scale. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/movie-reviews/taken-2. Their reviewer notes: “Compared to the first movie, Taken 2 has a more anti-revenge stance. The main character takes the law into his own hands, but he’s also a supreme problem-solver, using his head and the resources at his disposal. During this process, he learns how to better communicate with and trust his daughter, and they work together well. Additionally, through patience and understanding, he re-connects with his ex-wife. Love of family is a powerful theme.“. For me, this rings true and correctly measures the difference between the two movies.

Thank you for another fascinating insightful article. I am a Film producer dating all the way back to Robin Hood Prince of Thieves. And a Tv Producer who has revived both the Outer Limits and The Twilight Zone to network runs. – One note from your survey intrigues me. Why does Science Fiction seem to succeed embracing positivity and yet not so true for Fantasy? Can you share any thoughts? .

Hi Pen

I can’t give you an answer backed by data. My guess would be that sci-fi is often used as a way to say things that other films cannot. Many are parables, mortality tales, metaphorical messages, allegories, etc. Whereas fantasy seems to me to be less trying to say something and more about just enjoying the journey of the characters

Very late reply, but in case you’re still poking at the idea of Utopian vs Dystopian Sci-Fi, here’s a tought experiment:

on the whole, would you, the viewer, like to live in the world portrayed (aside from the details presented of the plot, which will no doubt involve extreme risk of death)?

On those grounds, for exmaple, I might say that the world of ‘Judge Dredd (1995)’ has some appeal – but the world of ‘Dredd (2011)’ definitely does not!

Hi Alex, it’s never too late for additional thoughts.

Your example is a great one as it highlights the subjective nature of the topic. Personally, I would have put both Dredd’s firmly in the dystopian bracket due to the Scorched Earth, overpopulation, gangs, bloc wars and overly-militaistic legal system. That said, Judge Dredd (1995) does show that some people are outside of the squaller whereas Dredd’s (2011) focus on the tower means that we don’t see any people whose lives we would want.

From a data perspective, we would either want an objective measure (i.e. running time) or an aggregation of many subjective measures to gain a broad consensus (i.e. Metascore). I haven’t yet found that with sci-fi.

We can’t predict the movies with their storyline and message. It’s completely based on the screenplay, If it attracts the audiences then it makes more profits. That’s why filmmakers are now planning to release the movies on the ott platform with revenue generation models. It will be helpful to monetize the videos with the right solution. After the covid, Lot of moviemakers and distributors are planned to build their own video streaming platform depends on their needs. FYI learn how to start your own ott platform from the scratch here.

Ref: https://hackernoon.com/how-to-start-your-own-ott-video-platform-in-2020-38r33yj

Stephen, thank you for this breakdown. I’m writing my bi-weekly blog post now on a similar subject and will surely reference this research (I believe you’re on my email list). To address your closing statements about the need for conflict in story, I recommend taking a deep look at seasons 1-4 of Star Trek: The Next Generation. Roddenberry faced a lot of resistance from traditional storytellers for framing humanity as having risen above internal conflict, even recognizing tensions in the trio relationship of Kirk, Spock, and McCoy in the previous ST series as a misrepresentation of the future. Roddenberry’s son made a great documentary that explores this called Trek Nation. I’d say that the current trajectory of the Star Trek franchise is far from the spiritual pinnacle of Roddenberry’s vision as achieved in ST: TNG seasons 1-4, and I believe this is due to a misinterpretation of what conflict means for storytelling. This widespread misinterpretation leads to a level of uniformity in international filmmaking that I see as evidence of the footprint of imperialism, down to the similarities of existential crises that are a result of a cultural perspective (or imposition) of certain morals and values. For me, these uniform conflicts are usually boring, leading me to look elsewhere for more evolved stories. From what I’m seeing across youth creativity in social media, or even from China’s recent announcement, Roddenberry’s perspective will become the norm over time, and these data sets can be a valuable aid in predicting the future of filmmaking.